Abstract

Background

Parents’ perceptions of their children’s behavior are culturally determined and may differ across cultures. The present study aimed to investigate parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ difficulties and the impact of problems in different cultural contexts in Nepal, and to explore the extent to which they align with child symptoms measured on a problem rating scale.

Methods

This study was conducted with parents of school-going adolescents in sixteen districts of Nepal. The Nepali version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)—Impact Supplement was used to assess parents’ perception of difficulties and the impact of problems, and the Child Behavior Checklist/6-18 (CBCL) was used as a symptom rating scale. We employed a mixed model approach for data analysis to address the hierarchical structure of our data.

Results

Parents’ perceptions of difficulties and the impact of problems did not differ between the Hindu “high caste”, the Hindu “low caste” and the indigenous/ethnic minority group. In contrast, the effect of caste/ethnicity was significant for parent ratings on the CBCL Total Problems as the “low caste” parents reported higher mean scores than parents from the indigenous/ethnic minorities group. Parents’ perception of difficulties and the impact of problems were moderately associated with their reports on the CBCL Total Problems. There was no moderating effect of caste/ethnicity on any of these associations.

Conclusion

Although cross-cultural differences emerged in parents’ ratings of symptoms, no differences emerged in their perception of difficulties and the impact of problems. Moderate associations between the CBCL Total Problems and perceived difficulties and the impact of problems suggest that clinicians should consider using supplement measurements in their assessment of child behavior problems. However, further studies are required to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents’ perception of children’s difficulties and the degree of impairment can vary based on cultural and socioeconomic factors [1,2,3]. Recent studies that have examined the link between culture and child behavior, emphasize the importance of investigating the cultural meanings of adaptive and maladaptive behaviors [4]. Problem behaviors in one ecocultural setting may have different significance and substantially different meanings in other settings [5]. Hence, parents in one culture might have different perceptions about the threshold for labeling a child’s behavior as deviant from parents in another culture, even if their children have similar problems [2, 6,7,8]. There may be cultural differences in coping, adaptation, and concern for children’s behavioral problems [5, 9]. Weisz et al. explained the importance of context-dependent meanings of mental symptoms: “Child psychopathology is inevitably the study of two phenomena — the behavior of children and the lens through which adults view child behavior” [10]. Previous cross-cultural research has consistently shown variations in parents’ ratings of children and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral problems (EBPs), indicating that they might be partly influenced by cultural norms [8, 11,12,13,14]. Recent studies have confirmed these findings [15,16,17,18]. In Asian cultures, cultural norms and values such as behavioral conformity, obeying adults, interdependence among family members, and inhibition of inner impulses have been emphasized [19, 20]. Hence, Asian parents may tend to perceive withdrawn- or internalizing behaviors in children and adolescents as less serious and worrisome as they might be more in tune with their own cultural norms and socialization goals [7].

When measuring EBPs cross-culturally, it should be noted that the frequency of behaviors reported on problem rating scales such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), may not always align with parents’ perception of difficulties. While screening instruments are valuable for obtaining a broad overview of child- and adolescent functioning by assessing the frequency of problem behaviors as reported by parents [21], they may not directly indicate whether a specific behavior is problematic. Parents might not necessarily perceive behaviors rated on such scales as burdensome to the environment or warranting interventions. Studies have shown that the degree of impairment associated with behaviors or mental health symptoms may vary based on cultural or socioeconomic factors [1]. Therefore, it is recommended to complement symptom rating scales with additional assessment procedures to evaluate parental perception and impact of problems as this approach ensures a more comprehensive understanding of the child’s difficulties and facilitates more effective intervention strategies [22, 23]. Measuring the impact of these problems may result in more accurate assessment and screening. Studies have demonstrated higher rates of disorders when symptoms alone are considered, and these rates are significantly reduced when impact is measured [1]. Consequently, including impairment ratings when screening for child difficulties reduces false positives and contributes to an efficient resource allocation. Compared to the Total Difficulties score on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), the Impact Supplement was found to be a better predictor of psychiatric caseness [24, 24] and service use [26]. Furthermore, the measurement of impact may also help with the issue of under-identification of children at risk given that several studies have identified groups of children who are impaired without exhibiting clinical levels of symptoms, both in clinic-referred samples [27, 28] and in non-referred samples [29, 30]. The measurement of impact in addition to symptom ratings in a screening context allows the detection of sub-clinical difficulties and the identification of as many children as possible who are at risk [23].

Despite the clear benefits of measuring parent perceptions and the impact of problems in addition to symptoms, Nepali studies on EBPs have yet to incorporate such measures in their assessments. There has been a modest body of literature on culture and mental health in Nepal [31]), and few Nepali studies have compared potential cultural differences in parents’ perceptions and reports of problems, although Nepal is a multicultural country in terms of caste and ethnicity. The present study aimed to (1) assess and compare Nepali parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ overall difficulties and the impact of problems between different castes/ethnic groups, (2) compare parents’ ratings of symptoms on a symptom rating scale (CBCL) between the same castes/ethnic groups, (3) examine the association between parents’ perceptions of difficulties and the impact of problems, and their ratings on the CBCL Total Problems scale, and (4) examine the possible moderating effects of caste/ethnicity on any of the associations between the SDQ-impact of problems and the CBCL symptoms.

Materials and methods

This study is part of a larger, cross-sectional survey of EBPs in school-going Nepali children and adolescents aged 6–18 years [32,33,34]. Two studies on the same sample, but limited to adolescents, have recently been published [35, 36].

Study site and population

Nepal is a low-middle-income country (LMIC) with a Human Development Index of 0.60, placing it in the medium human development category [37]. About one-fourth of the people live below the poverty level, i.e., earn less than US$ 1.25 per day. The country is topographically divided into three regions: The Himalayas (mountain region), which constitutes 6.1% of the population, the Middle Hills region (40.3%); and the Terai region (53.6% of the population) [38]. Approximately one-third (34%) of the people live in rural areas. The remaining two-thirds (66%) live in the urban areas. Children up to 18 years of age constitute approximately 36% of the total population [38]. Adolescents’ social and health vulnerabilities are high in Nepal, especially among girls and those belonging to the “low caste” Hindu group [39]. The child mental health situation is difficult due to the absence of a child and adolescent mental health policy, few mental health services, and a shortage of specialized human resources [40].

Castes/Ethnicity

Nepal is a multicultural country with 142 castes/ethnic groups and 124 mother tongues [41]. The Chhetri group was the largest, accounting for 16.5% of the total population, followed by Brahmin-Hill (11.3%), Magar (6.9%), Tharu (6.2%), Tamang (5.6%), Khas Kaami (Dalit) 5.0%, and Newar 4.6% [41]. The Chhetri and Brahmin-Hill represent the Hindu “high castes”, and the Khas Kaami (Dalit) represent the Hindu “low caste”. In Nepal, the term “caste” basically refers to a group of people who follow Hinduism, speak Nepali or any other Indo-Aryan languages, and have been traditionally ranked according to the Hindu religious values of purity and impurity. Casteism is still practiced, especially in the rural communities of Nepal, despite the law declaring it illegal (the New Civil Code of 1963) [42]. The “high caste” groups enjoy a privileged status in society while the “low caste” group, who resides both in the Terai and Hilly regions, occupy the lowest social rung. The “low caste” group (the Dalits) may experience pervasive caste-based discrimination and disadvantages in various spheres of life [42, 43]. The next four groups, Magar, Tharu, Tamang, and Newar, all belong to indigenous minority groups collectively known as the “Janajati” or indigenous/ethnic minorities. They have indigenous traditions and languages, and constitute over one-third of Nepal’s population but live as a minority in all 77 districts of Nepal [41]. The caste-based social structure in Nepal is complex and further complicated by the fact that each ethnic group may have a hierarchical system with distinct socio-cultural norms and practices. For example, Newars have a well-defined hierarchically based occupational caste system that ranges from the lowest to the highest, from cleaner to priest [44].

Participants and procedure

The participants were 1882 parents of school-going adolescents aged 11 to 18 years. Based on the population distribution of the three main ecological/geographical regions of Nepal, 16 districts (three districts from the mountain region, six districts from the Middle Hills region, six districts from the Terai region, and the Kathmandu district) and four schools (two government and two private) in each district were selected using a purposive sampling method. Given our nationwide study in a country with poor and time-consuming transportation and communication systems, the purposive sampling technique was chosen because of its cost-effectiveness and ease of data collection and travel. The children in each school were randomly selected using random number tables from Classes 6 to 10. Six students per class (3 boys and 3 girls) were selected. The data were collected in 2017 and 2018. The overall participation rate was 98.9%. The missing data were < 0.5% for each variable. More detailed information about the procedure has been provided in a previous paper [32]. The participants were categorized into three groups based on their caste/ethnicity, as described in a previous Nepali study [45]. According to the Nepal Census of 2011, all participants in the study belonged to the seven largest caste/ethnic groups [46]. The three main group categories were: (1) Brahmin and Chhetri (Hindu “high caste” group); (2) Janajati (indigenous/ethnic minorities group); and (3) Dalits (Hindu “low caste” group). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Board of the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC). A team of trained research assistants performed data collection and was monitored by the project leader. A meeting with the school management was conducted at each school, and an invitation letter was sent to the parents to participate in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the selected students. Both verbal and written information about the study were provided to the parents. Parents were given the CBCL, the Impact Supplement of SDQ, and a background information questionnaire to report on problem behaviors, the impact of problems, and socio-demographic- and family background data. Parents first filled in the CBCL questionnaires and then completed the SDQ-Impact supplement questionnaires independently of the research assistants, except for illiterate parents who were assisted in filling in the forms.

Measures

Impact supplement of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ)

The main instrument used in the present study was the Nepali version of the “Impact Supplement of the extended Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire” (SDQ) [47] elaborated by Goodman to explore the informant’s perception of a child’s difficulties, the impact of the difficulties in terms of distress and social impairment, and the burden to the family [23]. To measure parents’ perception of child difficulties, the first question of the SDQ Impact Supplement was used: "Overall, do you think that your child has difficulties in one or more of the following areas: emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get on with other people?” This question was scored on a 4-point scale: no, minor, definite, and severe. If the parents perceived “no difficulties,” items about the impact and burden of problems on the family were skipped and the impact was automatically scored as zero (no impairment). In the case of a positive response, the parents were further questioned about the impact of the problems. To assess distress, the question asked was: “Do the difficulties upset or distress your child?” A further question about the impact of problems was “Do the difficulties interfere with your child’s everyday life in the following areas: home life, friendships, classroom learning, and leisure activities?” The same options, i.e., “not at all”, “only a little”, “a medium amount”, and “a great deal” was provided for all four areas. The impact of problems was rated on a 4-point scale: 0 = not at all, 0 = only a little, 1 = quite a lot, and 2 = a great deal. The items concerning child distress (1 item) and social impairment (4 items) generated a total impact score ranging between 0 and 10 by adding the scores of all items using a “0-0-1–2” scale according to Goodman’s recommendation [23]. The SDQ impact score has high concurrent and predictive validity [25] and is acceptable for good internal consistency [25, 48].

Child behavior checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL/6–18 was used to assess adolescents’ EBPs, as reported by their parents. Written permission to use the Nepali version was granted by the copyright owner, which was made in connection with a Ph.D. dissertation [49]. The CBCL is a rating instrument commonly used worldwide and has been translated into more than 100 languages. It consists of 20 items measuring competencies and 120 items addressing behavioral problems and has established good psychometric properties [50]. The problem items were scored on eight syndrome scales, two broadband, higher-order subscales (Internalizing and Externalizing Problems), and a Total Problem scale. The Total Problem score was computed by summing the scores for all problem items [50]. The response format of questions on behaviors was 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true. The CBCL ratings are based on the child’s functioning over the last six months. An overall good internal consistency of the CBCL/6–18 syndrome scales was reported for the whole sample, i.e., the age group of 6–18 years in a study from Nepal [32]. Acceptable internal consistency was also observed in the adolescent age group targeted in the present study. Cronbach’s alphas for the syndrome scales were 0.72 (Anxious/Depressed), 0.68 (Withdrawn/depressed) 0.77 (Somatic Complaints), 0.67 (Social problems), 0.71 (Thought Problems), 0.77 (Attention Problems), 0.72 (Rule-Breaking Behavior) and 0.86 (Aggressive Behavior).

Statistical analyses

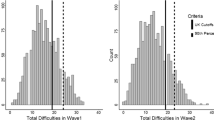

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 29.0 for Windows [51]. To (1) compare parent perception of difficulties and the impact of problems, and the CBCL Total Problems between three different caste/ethnic groups, to (2) examine the possible moderating effects of caste/ethnicity on the associations between CBCL symptoms and parents’ perception of difficulties and impact of problems, and (3) examine the association between parents’ ratings on the CBCL Total Problems scale and parent perceptions of difficulties and the impact of problems, we employed a mixed model approach to address the hierarchical structure of our data. Our data consisted of adolescents nested within classrooms (Level 2), classrooms nested within schools (Level 3), schools nested within enumerators (Level 4), and enumerators nested within districts (Level 5). This nested structure was modeled using random intercepts at each level to account for the dependencies observed at multiple levels. For continuous outcomes, such as the impact of problems and CBCL problems, we conducted a full 5-level linear mixed model (LMM) analysis, incorporating random intercepts for classrooms, schools, enumerators, and districts. This comprehensive approach allowed us to capture the variability and dependencies across all levels of data hierarchy. For ordinal outcomes, (i.e. perceived difficulties), we utilized a 3-level generalized linear mixed model (GLM), including random intercepts for classrooms and districts. Due to the challenges in estimating variance components at the enumerator and school levels for these ordinal outcomes, these levels were not included in the model. The significance level used in all tests was 0.01.

Results

Among the study participants (N = 1882), the highest representation was from the Hindu “high caste” group (Brahmin and Chhetri) (48.3%), followed by the indigenous/ethnic minorities group (the Janajati) (40.8%) and the Hindu “low caste” group (Khas Kaami / Dalits) (11.0%). 17.5% of all parents (total sample), perceived their adolescents to have either minor, definite, or severe difficulties in emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get on with other people. 21.4% of parents from the “high caste” group, 19.3% from the “low caste” group, and 12.3% from the indigenous/ethnic minorities group perceived either minor, definite, or severe difficulties in their adolescents.

Parents’ perception of Nepali adolescents’ difficulties–comparison between different caste/ethnic groups

We compared parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ difficulties between the three caste/ethnic groups. We included parents’ perception of adolescents’ difficulties as a dependent variable and added a random effect of district, school, and school class variables while controlling for the living area, parental educational level, father’s employment status, and CBCL Total Problems. We found no significant effect of caste/ethnicity on perceived difficulties (F = 1.14, p = 0.32). Parents from the Hindu “high caste” and “low caste” groups did not differ from parents in the indigenous/ethnic minorities group in their perception of adolescents’ difficulties (Table 1).

Cross-cultural comparison of the impact of Nepali adolescents’ problems across caste/ethnic groups as reported by their parents

We compared the impact of problems across caste/ethnic groups. We included the Total Impact score as a dependent variable while controlling for the living area, parental educational level, father’s employment status, and CBCL Total Problems. We found no effect of caste/ethnicity on the impact of problems. The “high caste group” and “low caste group” did not differ significantly from the ethnic minority group (Table 2).

Nepali parents’ ratings of adolescents’ EBPs on the CBCL Total Problems scale – comparison between different caste/ethnic groups

We compared the mean scores on the CBCL Total Problems for the different caste/ethnic groups while controlling for living area, parental educational level, and father’s employment status. We found that the overall effect of caste/ethnicity was not significant for Total Problems (p = 0.04). However, parents from the Hindu “low caste” group reported higher mean scores than parents from the Indigenous/ethnic minority group (p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Associations between the CBCL total problems and perceived difficulties and impact of problems

We tested the association between (1) CBCL Total Problems and Perceived Difficulties and (2) CBCL Total Problems and the Total Impact of Problems while controlling for the living area, parental educational level, and father’s employment status. We found a positive association between the Total Impact of problems and the CBCL Total Problems (F = 95.43, p < 0.001). Similarly, perceived difficulties were positively associated with Total Problems (F = 95.72, p < 0.001). However, all associations were only moderately high (Table 4).

Moderating effects of caste/ethnicity on the associations between the CBCL symptoms and the SDQ impact of problems

We examined whether caste/ethnicity had any moderating effect on the association between (1) CBCL Total Problems and SDQ Perceived Total Difficulties and (2) CBCL Total Problems and SDQ Total Impact of Problems while controlling for living area, parental educational level, and father’s employment status. The moderating effect of caste/ethnicity on the association between CBCL Total Problems and SDQ Perceived Difficulties was not significant (F = 1.57, p = 0.21). Likewise, we found no significant moderating effects of caste/ethnicity on the association between the CBCL Total Problems and the SDQ Total Impact (F = 0.97, p = 0.38).

Discussion

This study explored parents’ perceptions of their adolescents’ difficulties and the impact of problems between different caste/ethnic groups in Nepal. Further, it examined parent reports on a problem rating scale (the CBCL Total Problems) and the associations between those reports and parents’ perception of difficulties and the impact of problems, taking into consideration the possible moderation effect of caste/ethnicity.

In contrast to findings reported in the literature [9, 15, 52, 53], this study did not find cross-cultural differences in parents’ perceptions of difficulties and the impact of problems between different caste/ethnic groups in Nepal. Our findings may be attributed to various reasons. First, regardless of their caste/ethnicity, Nepali parents might share common attitudes and norms about child behavioral difficulties in the areas investigated in our study which would be consistent with the collectivistic values found in a society such as Nepal [19]. Social mobility, internal migration from rural to urban areas, inter-caste marriages, and subsequent cultural exchanges, as described in recent Nepali papers, might have blurred the lines between different groups of people [54,55,56], possibly leading to more common norms and more homogeneous parental perceptions. However, such societal mechanisms are complex and their impact on cultural group differences needs to be further explored in future studies to broaden our knowledge of parents’ perception of difficulties and the impact of children’s behavioral problems cross-culturally. Further, the reason behind the null findings may be due to insufficient power rather than the true absence of an effect that needs to be addressed in future studies. Another important reason for non-significant cross-cultural findings may be that the group categories used in this study, i.e., “Hindu high caste” group, “Hindu low caste” group, and “indigenous/ethnic minorities” group were too broad and heterogeneous to capture inter-group differences. For instance, the Janajati group consists of several ethnic groups, such as the Magar, Tharu, Tamang, and Newar, living within different cultural- and social contexts, although all of them live as minorities vis-à-vis the majority Hindus. Furthermore, the caste system itself is complex, with considerable heterogeneity, even within the same caste/ethnic group. Hence, our study required further replication. More detailed and extensive studies with better-defined cultural groups, and with a proper design to capture cultural differences in parents’ perceptions of child difficulties and the impact of problems are warranted.

Finally, Nepali parents’ perception of child difficulties was low across groups, only 17.5% of all parents perceived that their adolescents had either minor, definite, or severe difficulties. Detecting cross-cultural differences in low-prevalence samples is difficult, and non-significant results should be interpreted with caution.

On the other hand, cross-cultural differences in parent ratings on the CBCL Total Problems emerged, with parents from the Hindu “low caste” group reporting more problems. Adolescents in a “low caste” group are likely to be rated higher than other groups on a problem rating scale due to socio-economic adversity / low socio-economic status (SES) and caste-based discrimination prevailing in Nepali society [57] which increases the risk of adverse child mental health outcomes [32, 58,59,60]. A recent Nepali study suggested that adolescents who have a lot of ecocultural and contextual risk factors and live in unsupervised physical and social settings might have a higher risk of behavioral problems [11]. International studies have shown that socio-economically disadvantaged children and adolescents are at a greater risk of mental health problems [61, 62]. However, more studies are warranted to explore EBPs in “low caste” groups in Nepal.

The moderate association found in our study between CBCL symptoms and parental perceived difficulties, and the impact of problems is consistent with previous international studies [7, 24, 25, 63], suggesting that the parental threshold for describing child behavior as problematic might be different from how they report on measures of symptoms. For instance, Nepali parents might report internalizing behaviors in the CBCL, but at the same time report fewer worries and the impact of such behaviors due to the acceptance of withdrawn or internalizing behaviors in their society. However, future Nepali studies are required to confirm this finding.

Finally, we examined whether caste/ethnicity had a moderating effect on the associations between the CBCL problem scores on the one hand and parents’ perception of difficulties and the impact of problems on the other. When controlling for the living area, parental educational level, and father’s employment status, no moderating effect of caste/ethnicity on any of the above-mentioned associations was found. However, moderation effects are generally difficult to detect and are often small. Future studies with proper design to capture the intricacies inherent within the different cultural groups of Nepal might shed more light on the potential moderation or mediation effects of culture on the associations between symptoms and the impact of problems.

Limitations

This study has some inherent limitations that should be considered. First, it is important to acknowledge the limited generalizability of our study findings because of the purposive sampling method used to select districts and schools. The use of a probability sampling method in the selection of districts and schools would have enhanced the robustness of the process. Purposive sampling might have resulted in biased results (selection bias). Certain districts or schools may have unique characteristics that influence the results. To overcome these issues, we used a multilevel/mixed method approach in our analyses and controlled for contextual factors such as living area (rural, semi-urban, and urban), parental educational level, and father’s employment status. However, this may only partially adjust to the limitations mentioned above.

Second, perceived difficulties and the impact of problems were exclusively rated from the perspectives of parents which might be considered a limitation of this study. Only 17.5% of parents in the overall sample reported difficulties. Although parents know their children best, they may be biased by their own subjective needs and expectations. Due to the social desirability and stigma of mental disorders in Nepali society [64], parents may have chosen not to communicate their perception of their child’s difficulties and the impact of problems, leading to false negative results. Furthermore, the prevalence of parents’ perception of child difficulties was lowest in the indigenous/minority group (12.3%). One explanation for this could be that some parents belonging to this group might not have properly understood the questions due to low proficiency in the Nepali language and did not communicate this problem to research assistants.

To ascertain parental information, we could have included other research methods, such as additional qualitative interviews or participant observations. However, limited resources have prevented us from doing so. Furthermore, our study did not investigate the effect of recall bias on the CBCL ratings. Ratings on the CBCL are based on parents’ recall of their child’s functioning in the home context over the last six months. Due to the lack of adolescents’ self-reports and teachers’ reports on perceived difficulties and the impact of problems, we could not make a comparison between different informants. Future Nepali studies using multiple informants that report both difficulties and impacts are warranted.

Third, although we measured both problems and the impact of problems in this study, we were unable to identify clinical cases within the present study design. We do not have clinical cut-off scores for Nepal that indicate whether a child’s symptoms are sufficiently severe to be considered a clinical problem (caseness). SDQ norms for Nepal, and norms appropriate to other South-Asian countries have not yet been developed. Preliminary findings suggest that the use of British norms may increase the prevalence rates in these countries [65]. Hopefully, future studies will address this important issue by providing separate SDQ norms for Nepal.

Finally, although we controlled for parental educational level and the father’s employment status in the analyses, this might be inadequate to capture the complexity of the families’ socio-economic status. In future studies, it is recommended to delve deeper into the relationship between cultural- and socio-economic factors and to examine both their influences on parents’ perception of their child’s difficulties and the impact of problems.

Clinical implications

Cross-cultural knowledge about possible differences and similarities in parents’ perception of adolescents’ difficulties and the impact of problems would be relevant to clinicians when assessing mental health symptoms and treating problems in multicultural societies such as Nepal. Our findings suggest that in their assessments and diagnostic procedures, clinicians should pay attention to the cultural and social context of the child, including parents’ norms and perceptions, rather than focusing solely on children’s symptoms on rating scales. Moderate associations between parents’ rating of symptoms and parents’ reports on the impact of problems suggest that clinicians should be more aware of the possible discrepancies between reported symptoms and functional impairment. Functional impairment is a key factor in determining the clinical importance of mental health problems in children and adolescents. However, assessing impairment has been overlooked by researchers and clinicians. The partial unlinking of symptoms and their impact has implications for clinicians’ prediction of psychiatric disorders, decisions regarding the diagnostic process, and evaluation of treatment [66]. Understanding functional impairments may be particularly important in LMICs, where a better understanding of the social impact of mental health problems on children and adolescents is crucial for clinical services.

Conclusions

This study examined cross-cultural differences in Nepali parents’ perceptions of their adolescents’ difficulties and the impact of problems. Contrary to the cross-cultural differences found in parent ratings on the CBCL Total Problems scale, we found no differences in parent perception of difficulties and the impact of problems between the caste/ethnic groups used in this study. Furthermore, parent-reported symptoms on the CBCL correlated moderately with parent perceptions and the impact of problems, indicating the need for clinicians to include an assessment of social impairment and parents’ perception of problems in addition to symptoms rated on a symptom rating scale.

Data availability

The datasets used in the present study are provided as supplementary information files.

References

Rapee RM, Bőgels SM, van der Sluis CM et al (2012) Annual research review: conceptualizing functional impairment in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:454–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02479.x

Peverill M, Dirks MA, Narvaja T et al (2021) Socioeconomic status and child psychopathology in the United States: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clin Psychol Rev 83:101933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101933

Song JH, Cho SI, Trommsdorff G, Cole P, Niraula S, Mishra R (2023) Being sensitive in their own way: parental ethnotheories of caregiver sensitivity and child emotion regulation across five countries. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1283748

Chen X (2020) Exploring cultural meanings of adaptive and maladaptive behaviors in children and adolescents: a contextual-developmental perspective. Int J Behav Dev 44:256–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419877976

Kirmayer LJ, Swartz L (2013) Culture and global mental health. In: Patel V, Minas IH, Cohen A, Prince M (eds) Global Mental Health: Principles and Practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 41–62

Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D et al (1998) Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health 88(1):75–80. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.88.1.75

Weisz JR, Suwanlert S, Chaiyasit W et al (1988) Thai and American perspectives on over- and undercontrolled child behavior problems: exploring the threshold model among parents, teachers, and psychologists. J Consult Clin Psychol 56:601–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.4.601

Lambert MC, Weisz JR, Knight F, Desrosiers MF, Overly K, Thesiger C (1992) Jamaican and American adult perspectives on child psychopathology: Further exploration of the threshold model. J Consult Clin Psychol 60(1):146–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.60.1.146

Javo C, Ronning J, Handegård B, Rudmin F (2009) Cross-informant correlations on social competence and behavioral problems in Sami and Norwegian preadolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18:154–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0714-8

Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Eastman KL et al (1997) Developmental psychopathology and culture: Ten lessons from Thailand. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR (eds) Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder. Cambridge University Press, pp 568–592

Burkey MD, Ghimire L, Adhikari RP et al (2016) The ecocultural context and child behavior problems: a qualitative analysis in rural Nepal. Soc Sci Med 159:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.020

Chavez LM, Shrout PE, Alegría M et al (2010) Ethnic differences in perceived impairment and need for care. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:1165–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9428-8

Janssen MMM, Verhulst FC, Bengi-Arslan L et al (2004) Comparison of self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in Turkish immigrant, Dutch and Turkish adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:133–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0712-1

Stevens GWJM, Pels T, Bengi-Arslan L et al (2003) Parent, teacher and self-reported problem behavior in The Netherlands: comparing Moroccan immigrant with Dutch and with Turkish immigrant children and adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:576–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0677-5

Bevaart F, Mieloo CL, Jansen W et al (2012) Ethnic differences in problem perception and perceived need for care for young children with problem behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:1063–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02570.x

Biel MG, Kahn NF, Srivastava A et al (2015) Parent reports of mental health concerns and functional impairment on routine screening with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Acad Pediatr 15:412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.01.007

Runge RA, Soellner R (2022) Cultural bias in parent reports: the role of socialization goals when parents report on their child’s problem behavior. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01464-y

Yang H-J, Kuo Y-J, Wang L, Yang C-Y (2014) Culture, parenting, and child behavioral problems: a comparative study of cross-cultural immigrant families and native-born families in Taiwan. Trans cult Psychiatry 51:526–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461514532306

An D, Eggum-Wilkens ND, Chae S, Hayford SR, Yabiku ST, Glick JE, Zhang L (2018) Adults’ conceptualizations of children’s social competence in Nepal and Malawi. Psychol Dev Soc J 30(1):81–104

Yong GH, Lin MH, Toh TH, Marsh NV (2023) Social-emotional development of children in Asia: a systematic review. Behav Sci (Basel) 13(2):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020123

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2013) The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Applications in forensic contexts. In: Archer RP, Wheeler EMA (eds) Forensic uses of clinical assessment instruments. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp 311–345

Achenbach TM, Becker A, Döpfner M et al (2008) Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x

Goodman R (1999) The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(5):791–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00494

Lai KYC, Leung PWL, Luk ESL, Wong ASL (2014) Use of the extended strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) to predict psychiatric caseness in Hong Kong. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45:703–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0439-5

Stringaris A, Goodman R (2013) The value of measuring impact alongside symptoms in children and adolescents: a longitudinal assessment in a community sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:1109–1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9744-x

Janssens A, Deboutte D (2009) Screening for psychopathology in child welfare: the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) compared with the achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18:691–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0030-y

Gadow KD, Kaat AJ, Lecavalier L (2013) Relation of symptom-induced impairment with other illness parameters in clinic-referred youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:1198–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12077

Huculak S, McLennan JD (2014) Using teacher ratings to assess the association between mental health symptoms and impairment in children. Sch Ment Heal 6:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-013-9107-3

Angold A, Costello EJ, Farmer EM et al (1999) Impaired but undiagnosed. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:129–137. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199902000-00011

Wille N, Bettge S, Wittchen H-U et al (2008) How impaired are children and adolescents by mental health problems? Results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(Suppl 1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-1005-0

Chase LE, Sapkota RP, Crafa D, Kirmayer LJ (2018) Culture and mental health in Nepal: an interdisciplinary scoping review. Glob Ment Health (Camb) 5:e36. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2018.27

Ma J, Mahat P, Brøndbo PH et al (2021) Parent reports of children’s emotional and behavioral problems in a low- and middle-income country (LMIC): an epidemiological study of Nepali schoolchildren. PLoS ONE 16:e0255596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255596

Ma J, Mahat P, Brøndbo PH et al (2022) Family correlates of emotional and behavioral problems in Nepali school children. PLoS ONE 17:e0262690. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262690

Ma J, Mahat P, Brøndbo PH et al (2022) Teacher reports of emotional and behavioral problems in Nepali schoolchildren: to what extent do they agree with parent reports? BMC Psychiatry 22:584. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04215-4

Adhikari S, Ma J, Shakya S, Brøndbo PH, Handegård BH, Javo AC (2023) Self-reported emotional and behavioral problems among school-going adolescents in Nepal-A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 18:e0287305. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287305

Adhikari S, Ma J, Shakya S, Brøndbo PH, Handegård BH, Javo AC (2024) Cross-informant ratings on emotional and behavioral problems in Nepali adolescents: A comparison of adolescents’ self-reports with parents’ and teachers’ reports. PLoS ONE 19(5):e0303673. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303673

UNDP (2020) The Next Frontier: Human development and the Anthropocene briefing note for countries on the 2020. Human Development Report Nepal.

Government of Nepal (2023) National Population and Housing Census 2021: Brief results (National Report). National Statistics Office, Kathmandu, Nepal. 1:84. https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/results

Adhikari RP, Upadhaya N, Pokhrel R et al (2016) Health and social vulnerability of adolescents in Nepal. SM J Public Health Epidemiol 2(3):1032

Chaulagain A, Kunwar A, Watts S et al (2019) Child and adolescent mental health problems in Nepal: a scoping review. Int J Ment Heal Syst 13:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0310-y

Government of Nepal, (2023). National population and housing census, 2021: National report on caste/ethnicity, language, and religion. National Statistics Office, Kathmandu, Nepal. https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/results/downloads/caste-ethnicity

Chhetri RG (2022) Influence of casteism in modern Nepal: a sociological perspective. Marsyangdi J 3(1):122–127

Chalaune BS (2020) Dalit students’ perceptions and experiences of caste-based discrimination in Nepalese schools. Int J Res -Granthaalayah 8(8):147–154. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v8.i8.2020.977

Shakya D (2010) Education, economic and cultural modernization, and the Newars of Nepal. In: Kapoor D, Shizha E (eds) Indigenous knowledge and learning in Asia/Pacific and Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Tol WA et al (2008) Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. JAMA 300:691–702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.6.691

Government of Nepal (2014) Population monograph of Nepal: Volume II (Social demography). Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu, Nepal Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/wphc/Nepal/Nepal-Census-2011-Vol1.pdf

Double-sided version with impact supplement: P4–17 - SDQ and impact supplement for the parents of 4–17-year-olds. Available from: https://www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/b3.py?language=Nepali [cited 2024 Aug 6].

Aitken M, Martinussen R, Tannock R (2017) Incremental validity of teacher and parent symptom and impairment ratings when screening for mental health difficulties. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45:827–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0188-y

Mahat P (2007). A study of the prevalence and pattern of psychological disturbances in school-going children and adolescents. PhD thesis. Fac Humanit Soc Sci Tribhuvan Univ.

Achenbach TM, Rescorla L (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, Burlington, VT

IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0.

Bevaart F, Mieloo CL, Donker MCH et al (2014) Ethnic differences in problem perception and perceived need as determinants of referral in young children with problem behavior. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23:273–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0453-3

Leijten P, Raaijmakers M, Castro B, Matthys W (2016) Ethnic differences in problem perception: immigrant mothers in a parenting intervention to reduce disruptive child behavior. Am J Orthopsychiatry 86(3):323–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000142

Aryal B (2024) Transformations of parental socio-economic characteristics into the married couple in rural Nepal. Asian J Populat Sci 3(1):31–42. https://doi.org/10.3126/ajps.v3i1.61829

Basnet C, Jha R (2019) Crossing the Caste and Ethnic Boundaries: Love and Intermarriage Between Madhesi Men and Pahadi Women in Southern Nepal. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Internet]. Oct 29 [cited 2024 Jun 21]; Available from: https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5802

Karki PD. Internal Migration in Nepal: Resilience to Departure and Host Area. Rural Development Journal, Vol. IV, March 2024, N.S. 1144, 2080 B.S., ISSN 2382–5235

Thapa R, van Teijlingen E, Regmi PR, Heaslip V (2021) Caste exclusion and health discrimination in South Asia: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Public Health 33:828–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211014648

Kiang L, Folmar S, Gentry K (2020) “Untouchable”? Social status, identity, and mental health among adolescents in Nepal. J Adolesc Res 35:248–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558418791501

Kohrt BA, Speckman RA, Kunz RD et al (2009) Culture in psychiatric epidemiology: using ethnography and multiple mediator models to assess the relationship of caste with depression and anxiety in Nepal. Ann Hum Biol 36:261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460902839194

Vines AI, Ward JB, Cordoba E, Black KZ (2017) Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health: a review and future directions for social epidemiology. Curr Epidemiol Rep 4:156–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-017-0106-z

Reiss F (2013) Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

Reiss F, Meyrose A-K, Otto C et al (2019) Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS ONE 14:e0213700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213700

Stone LL, Otten R, Engels RCME et al (2010) Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13:254–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2

Gurung D, Poudyal A, Wang YL et al (2022) Stigma against mental health disorders in Nepal conceptualized with a ‘what matters most’ framework: a scoping review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 28(31):e11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000809

Bhat NA, Roopesh BN (2022) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: preliminary findings about local cut-offs, prevalence, and gender differences in emotional and behavioral difficulties among Indian adolescents. Indian J Pediatr 89:211–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-04032-9

Gordon M, Antshel K, Faraone S et al (2006) Symptoms versus impairment: the case for respecting DSM-IV’s Criterion D. J Atten Disord 9:465–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054705283881

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participating Nepali adolescents and their parents, and to the team of data enumerators and supervisors for making this study possible. We also extend our gratitude to the child and adolescent psychiatry team at Kanti Children’s Hospital, Kathmandu, and the Adolescent Mental Health Unit at Mental Hospital, Lagankhel for their support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway). This study was funded by the Norwegian Partnership Program for Global Academic Cooperation (NORPART), 2018/10039 project: “Collaboration in Higher Education in Mental Health between Nepal and Norway”, and the non-governmental organization “Child Workers in Nepal” (CWIN-Nepal). The NORPART project funded the expenditures of the research work itself, (URL: https://diku.no/en/programmes/norpart-norwegian-partnership-programme-for-global-academic-cooperation/), and CWIN-Nepal funded the salary of the principal investigator (URL: https://www.cwin.org.np/). The charges for online publication were funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT-The Arctic University of Norway. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sirjana Adhikari contributed to conceptions, research planning, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Jasmine Ma contributed to the research planning and data collection and reviewed the manuscript. Suraj Shakya and Per Håkan Brøndbo reviewed the manuscript and made significant additions to it. Bjørn Helge Handegård assisted as a statistician in the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Anne Cecilie Javo contributed to the conception, research planning, and data analysis, supervised and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content; and provided significant input to the manuscript text. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) (ref. no. 824, reg. no: 470/2020). All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the selected students. Data collection and storage were carried out following NHRC rules. Records from the study were kept strictly confidential and locked in a fire-resistant cabinet. No person other than the researcher had access to the data. All electronic information was coded and secured using password-protected files. All personally identifiable information was removed from the data set, and no information that would make it possible to identify any participant was shared or published.

Consent for publication

It is not applicable, as individual details are not provided in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adhikari, S., Ma, J., Shakya, S. et al. Parents’ perception of adolescents’ difficulties and impact of problems in different castes and ethnic groups in Nepal. Do they converge with the frequencies of symptoms reported on the child behavior checklist (CBCL)?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-025-02835-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-025-02835-1