Abstract

We present a case of giant fetal hepatic hemangioma to illustrate the impact of ultrasound monitoring on treatment outcomes. Prenatal ultrasound revealed cardiac enlargement, leading to a cesarean section. The neonate had multiple vascular anomalies, including hepatic artery-portal fistula, portal-hepatic venous fistula, and a giant arteriovenous fistula for the abnormal right internal thoracic artery with portal vein, causing progressive pulmonary hypertension. Postnatal embolization and propranolol treatment resulted in significant tumor shrinkage on ultrasonography and resolution by age 2 years. This report highlights the value of detailed prenatal ultrasound monitoring in guiding effective treatment and improving outcomes for giant fetal hepatic hemangioma, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Liver tumors in the fetal and neonatal periods are rare, comprising approximately 5% of all tumors. Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign liver tumors, often detected incidentally on prenatal ultrasound. While small-to-medium-sized hemangiomas usually resolve spontaneously, giant fetal hepatic hemangiomas with diameters over 40 mm [1] can cause serious complications such as fetal hydrops, heart failure, coagulation disorders, and tumor rupture, which are potentially life-threatening [2]. This study presents a case of giant fetal hepatic hemangioma diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound at 37 weeks gestation and discusses the treatment and regression in newborns, providing valuable insights for the prenatal diagnosis, counseling, and management of giant fetal hepatic hemangioma.

Case report

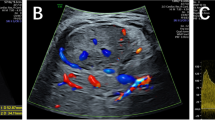

A 23-year-old primigravida was referred to our hospital at 37 weeks gestation owing to suspected fetal abnormalities detected on prenatal ultrasonography at another facility. The maternal history and early pregnancy ultrasounds were unremarkable. At transfer, the ultrasound revealed an enlarged fetal right atrium, cardiothoracic ratio of 0.69, and dilated hepatic veins. A solid, irregular mass measuring 45 mm × 27 mm, closely associated with the right hepatic lobe, was identified; the internal echo was heterogeneous, and several small cystic echoes were seen (Fig. 1a). Color Doppler ultrasound (US) showed prominent vascularity within the lesion, surrounding it as a ring. The stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands were normal; no abnormalities were noted in the blood flow of the umbilical artery and middle cerebral artery, with no hydrops.

Imaging images of patients before and after childbirth. a Fetal ultrasound reveals a complex mass in the fetal abdomen. b A “honeycomb” mass in the right lobe of the liver. c Color Doppler US shows abundant turbulent blood flow, indicating involvement of the right portal vein branch in hepatic artery-portal fistula. d A “honeycomb” mass in the left lobe of the liver. e Color Doppler US shows abundant blood flow, indicating portal-hepatic venous fistula of their left branch. f The right internal thoracic artery is significantly widened, tortuous, and downward sloping; its end entered the left lobe of the liver and then branched out to connect with the left branch of the portal vein. g Significantly enlarged right atrium and right ventricle with severe tricuspid regurgitation. h, i Transhepatic arterial embolization shows significant thickening of the hepatic artery and multiple fistulas visible in its branches. j Arteriography shows thickening and tortuous course of the right thoracic artery, supplying blood to the liver, with multiple clusters of blood vessels visible. k Cardiovascular computed tomography angiography shows thickening and tortuous course of the right thoracic artery, which enters the liver at the end and forms arteriovenous fistulas with the liver. l Intrahepatic hemangioma, re-examined after 6 months

Based on this assessment of cardiac disease and abdominal mass, an elective cesarean section was performed at 37 + 2 weeks, delivering a female infant weighing 2750 g with Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at 1 min and 5 min, respectively.

Given the prenatal findings, an abdominal ultrasound was conducted immediately after birth via color Doppler US, Revealed several cavernous liver masses, with the largest measuring 48 mm × 35 mm, and numerous turbulent-flow vessels inside. There was mild widening of the portal vein and significant dilatation of the hepatic veins, celiac axis, and the proper hepatic artery. It identified a hepatic artery-portal fistula involving the right branch of the portal vein (Fig. 1b, c) and a portal-hepatic venous fistula with multiple branching connections (Fig. 1d, e). A rare finding was that the right internal thoracic artery was significantly widened, tortuous, and downward sloping; its end entered the left lobe of the liver and then branched out to connect with the left branch of the portal vein, which dilated the portal vein system and formed an arteriovenous fistula between the right internal thoracic artery and the left branch of the portal vein (Fig. 1f). Echocardiography showed a tricuspid regurgitant velocity of 4.7 m/s (pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 88 mmHg), a 4.9-mm atrial septal defect (bi-directional shunt), an arterial ductus arteriosus of 3.0 mm (bi-directional shunt), and dilatation of the right atrium and right ventricle, indicating pulmonary hypertension. Simultaneously, cardiovascular computed tomography angiography was conducted and confirmed vascular abnormalities (Fig. 1k). Chest radiography revealed an enlarged cardiac silhouette and increased pulmonary vascularization without pneumonia.

The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension secondary to congenital hepatic hemangioma caused by increased pulmonary blood flow from hepatic vascular shunts. The internal thoracic artery formed an arteriovenous fistula with the liver, producing an extraordinarily thick internal thoracic artery. Treatment included diuretics, digoxin, and fluid restriction, with serial dynamic echocardiography monitoring pulmonary hypertension. Nevertheless, pulmonary artery pressure increased from 88 to 110 mmHg and then to 124 mmHg (Fig. 1g). Following coagulation and hematological tests, including liver and thyroid function tests, the benefits and risks of arteriography and transhepatic arterial embolization were assessed; a decision was made to embolize the internal thoracic artery and the hepatic artery. (The portal vein supplies 70% of the blood to the liver, whereas the hepatic artery supplies 30%. Three hepatic veins drain blood from the liver). Under general anesthesia, a curved 4F catheter was introduced into the innominate artery (Fig. 1j). After visualization of the right internal thoracic artery, a microcatheter was placed on the surface of the diaphragm and anterior to the bifurcation of the hepatic tumor vessels. The branches at all levels were embolized separately with gelatin sponge particles, and the right internal quincunx artery was blocked to the blind end with gelatin sponge strips. The 4F catheter was replaced and inserted into the celiac axis and directed to the proper hepatic artery (Fig. 1h, i). After angiography, the right and left hepatic arteries and their branches were embolized with gelatin sponge particles under the guidance of digital subtraction angiography.

Postoperatively, the neonate gradually stabilized. Abdominal ultrasound showed gradual shrinkage of liver mass, and serial echocardiography revealed a rapid decrease in pulmonary artery pressure (124 mmHg to 59 mmHg and then to 33 mmHg). To enhance tumor regression, we initiated oral propranolol 3 weeks post-surgery. The internal echo, size, and blood flow of the lesions were monitored during the follow-up period via ultrasound (Table 1, Fig. 2). The lesion gradually decreased in size, reduced to 20 mm × 10 mm by 6 months (Fig. 1l) and 12 mm × 10 mm at 1 year, and all lesions had well-defined boundaries, without blood flow on color Doppler US. The propranolol was discontinued, and by 2 years, the tumor had completely disappeared.

Discussion

Ultrasound, non-invasive and non-radioactive, is crucial for prenatal diagnosis and neonatology. Fetal liver tumors, such as hepatic hemangiomas, are rare benign tumors resulting from abnormal blood vessel growth. Giant fetal hepatic hemangiomas exceeding 40 mm are even rarer. While early pregnancy detection is challenging, these tumors are more visible in late pregnancy owing to increased blood accumulation. Typically identified between 28 and 40 weeks via ultrasound, hemangiomas vary in size and appearance. Small ones show uniform hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas, while larger ones present heterogeneous echoes, honeycomb patterns, and calcifications [3].

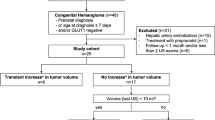

Hepatic hemangiomas (60%) are the most common liver tumors in newborns, followed by mesenchymal hamartomas (23%), hepatoblastomas (16%), hepatic metastases, and others (1%), identified by ultrasound [4] (Table 2).

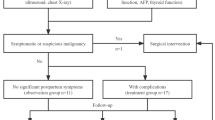

Prenatal detection of fetal hepatic hemangioma requires regular follow-up to identify potential life-threatening issues, typically every 2–4 weeks. If shunting with high-flow or increased flow through the hepatic and portal vessels occurs, the mass rapidly increases, or if the fetus develops high-output heart failure, edema, hemolytic anemia, or severe thrombocytopenia, the assessment is adjusted to every 1–2 weeks, and an echocardiogram is especially valuable in evaluating cardiac function. If the diagnosis is difficult, a magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan may be performed to confirm it. Routine blood tests, thyroid function, coagulation, alpha-fetoprotein, and echocardiography may be performed simultaneously to confirm the presence of complications such as heart failure, tumor rupture and bleeding, Kasabach–Merritt syndrome, and congenital hypothyroidism and rule out liver malignancy, the absence of fetal heart failure, and adverse outcomes such as stillbirth [5].

There is no consensus on the dynamic monitoring and treatment of hepatic hemangiomas, and management is tailored to tumor classification and the newborn’s clinical condition [5, 6]. Fetuses with hepatic hemangiomas should have an ultrasound scan immediately after birth, particularly for giant fetal hepatic hemangioma. Asymptomatic infants are generally monitored for at least 1 year, as most hemangiomas regress spontaneously by age 1 year. Symptomatic cases presenting with dyspnea, heart failure, or hypothyroidism require medical treatment, transhepatic arterial embolization, or surgical resection. Propranolol is the first choice for treating hepatic hemangiomas in infants and children. In addition, combining rapamycin with propranolol and glucocorticoids may enhance therapeutic outcomes. Relatively, their side effects are greater. In children with poor response to medical treatment, high-flow arteriovenous shunting, and rapidly deteriorating cardiac function, urgent transcatheter hepatic arteriovenous fistula embolization is highly effective. When medical treatment fails and symptoms are severe, with focal or multiple lesions, surgical resection is effective. Regardless of the treatment plan, regular follow-up evaluations should be conducted through ultrasound examination to make the most reasonable adjustments promptly.

Ultrasound is non-invasive, effective, inexpensive, and practical for diagnosing hepatic hemangiomas. Its continuous dynamic scanning and color Doppler US provide detailed insights into the blood supply of the tumor and the function of other blood vessels in the liver and heart, making it the preferred method [6]. For prenatal detection of giant liver hemangiomas, a systematic assessment of the fetal condition is crucial for determining delivery timing, postnatal examination, treatment options, and follow-up care.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Pott BE, Paek BW, Yoshizawa J et al (2003) Giant fetal hepatic hemangioma. Case report and literature review. Fetal Diagn Ther 18:59–64

Aslan H, Dural O, Yildirim G, Acar DK (2013) Prenatal diagnosis of a liver cavernous hemangioma. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 32:341–345

Zhang D, Wang J (2019) Prenatal diagnosis and management of fetal hepatic hemangioma. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 48:439–445

Birkemeier KL (2020) Imaging of solid congenital abdominal masses: a review of the literature and practical approach to image interpretation. Pediatr Radiol 50:1907–1920

Zavras N, Dimopoulou A, Machairas N et al (2020) Infantile hepatic hemangioma: current state of the art, controversies, and perspectives. Eur J Pediatr 179:1–8

Section of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Branch of Pediatric Surgery, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Group of Oncology, the Society of Pediatric Surgery, Chinese Medical Association (2020) Expert consensus on diagnosing and treating hepatic hemangioma in children. Chin J Pediatr Surg 41:963–970

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W XY collected data and figures, drafted manuscript, manuscript submission.

J J contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content

W G critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weng, X., Jiang, J. & Wen, G. Ultrasonographic diagnosis and follow-up of a special type of giant fetal hepatic hemangioma. Pediatr Radiol 55, 1024–1028 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-025-06196-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-025-06196-4