Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection has been investigated as a potential risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Some studies suggest a possible link between the two conditions. The purpose of this study is to study the relationship between H. pylori infection and NAFLD in pediatrics and its relation to NAFLD grades. A case–control study to identify predictors of NAFLD and a comparative cross-sectional approach to determine factors affecting NAFLD grades were adopted. One hundred NAFLD children (ultrasound-based) and a control group of 100 non-NAFLD children were recruited. Both groups were evaluated by detecting H. pylori stool antigen. Immunoglobulin G antibodies to Cag A (cytotoxin-associated gene A), Vac A (vacuolating cytotoxin A), Gro EL (chaperonin Gro EL), HCPC (Helicobacter cysteine-rich protein C), and Ure A (Urease subunit A) were assessed in the serum of those with positive stool antigen. H. pylori infection was significantly higher in NAFLD children compared to the control group (64% versus 25%, p-value < .001). (NAFLD children showed higher Cag A and Vac A positivity (34, 10%) versus (2%, 0%) in the control group, respectively, p-value < .001). The regression model showed that H. pylori positivity (OR (odds ratio) = 5.021, 95% CI (confidence interval): 1.105–22.815), homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (Homa IR) (OR = 18.840, 95% CI: 3.998–88.789), waist percentile (OR = 1.184, 95% CI: 1.044–1.344), and triglycerides (OR = 1.029, 95% CI: 1.012–1.047) were predictors for NAFLD. Cag A positivity (OR = 2.740, 95% CI: 1.013–7.411) was associated with higher NAFLD grade (grade 2 fatty liver).

Conclusions: H. pylori infection could increase the risk of NAFLD in children. Triglycerides, waist circumference, and Homa IR are significant independent predictors of NAFLD.

What is Known: |

• NAFLD has become one of the most common liver diseases among children because of the increased prevalence of pediatric obesity. • Dyslipidemia and insulin resistance play a central role in NAFLD pathogenesis. • NAFLD could be explained by the multiple-hit hypothesis. The gut microbiota is an important factor in this hypothesis (gut liver axis). |

What is New: |

• Helicobacter pylori infection could increase the risk of NAFLD in children. • H. pylori Cytotoxin-associated gene A (Cag A) positivity is associated with higher NAFLD grade. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become one of the most common liver diseases among children because of the increased prevalence of pediatric obesity [1]. Its prevalence in Egypt reached 15.7% [2].

NAFLD is defined by the detection of hepatic steatosis by either imaging or histology after the exclusion of other causes of liver disease [3]. NAFLD is explained by the multiple-hit hypothesis. The gut microbiota effect represents an important factor in this hypothesis [4]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is now a growing health problem, and there is growing evidence of an association between H. pylori and NAFLD [5]. H. pylori can alter the gut microbiome and can increase gut permeability allowing the translocation of bacteria and inflammatory mediators into the portal circulation. This leads to the progression of NAFLD [5]. H. pylori also can penetrate and stay in the hepatocytes [6]. It is mainly dependent on cytotoxin-associated gene A (Cag A) and vacuolating cytotoxin A (Vac A) status which are the main determinants of H. pylori pathogenicity [6]. The relationship between H. pylori and NAFLD was studied in several research in adults, but to date, there is no clear answer to the questions regarding this. Moreover, because of a lack of adequate data on children, this research aimed to study this relationship among children attending the hepatology and nutrition clinic at Alexandria University Children’s Hospital (AUCH).

Methods

Study design

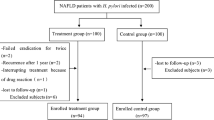

A case–control study design was adopted to identify significant predictors of NAFLD. Moreover, to determine factors that significantly affect NAFLD grades, a comparative cross-sectional approach was adopted. The study was conducted from November 2022 till November 2023.

Study participants

All obese children aged 2–18 years attending the outpatient hepatology and nutrition clinic at AUCH were assessed for fatty liver by ultrasound. Children with dyspeptic symptoms were excluded. Children with fatty liver due to other causes rather than NAFLD (e.g., viral hepatitis, celiac disease, Wilson disease, history of steatotic drug intake as corticosteroids) were excluded from the study. One hundred obese children with fatty liver and a control group of 100 obese children with normal ultrasound (who attend the nutrition clinic at AUCH seeking nutritional advice for the obesity problem), matched for age and sex, were selected. Sample size was calculated using the Epi Inf-7 program [7] based on an expected prevalence of H. pylori infection of 68% among NAFLD (in similar research) [8] as compared to 41% [9] among healthy children, as reported in recent literature with a minimum of 77 children per group was required to test hypothesis at 5% level of significance and achieve 90% power. Informed consent was taken from the guardians of all children.

NAFLD diagnosis

Because literature about transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography is limited in pediatrics [10]. Ultrasound abdominal examination was done by a single expert radiologist using a 4.5 MHz convex probe (Mindray Diagnostic Ultrasound System; Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics, China). Fatty liver was graded as follows: grade 0, grade 1, grade 2, and grade 3 [11].

History and examination

Demographic data and medical history were collected from both groups. Socioeconomic status scores were determined [12]. Examination namely anthropometric measurements, blood pressure measurement, and abdominal examination were performed. BMI, WC, SBP, and DBP percentiles were determined [13, 14].

Laboratory investigations

About 1 g of stool from each child was collected in a 5 ml sample diluent to be assayed for H. pylori antigen using Enzyme Immunoassay Test (ELISA) technique kit (Eagle Biosciences, Inc., Amherst, NH, USA) [15]. There was no history of acid-suppressive medications or antibiotic intake within 4 weeks before testing.

Three milliliter of venous blood was collected in a BD vacutainer® tube from every child under an aseptic technique after overnight fasting. Serum was used for assay of lipid profile, liver enzymes, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) [16,17,18,19]. Part of the serum was kept at − 80 °C to be used for detection of H. pylori virulence factors in patients with positive stool antigen using Line immunoassay test kit for detection of IgG antibodies to cytotoxin-associated gene A (Cag A), vacuolating cytotoxin A (Vac A), chaperonin Gro EL (Gro EL), Helicobacter cysteine-rich protein C (HCPC), and Urease subunit A (Ure A) [20].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Numerical variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and range. Comparison between groups was done using independent samples t-test and ANOVA for normally distributed variables. On the other hand, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for not normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were represented as numbers and percentages and compared using the Chi-square test. A multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify significant predictors of NAFLD after controlling for confounding factors using only factors that showed statistical significance in the univariate model and might be a risk factor for NAFLD. Ordinal logistic regression analysis was conducted to test significant predictors of higher NAFLD grades. Analysis was done at a 5% level of significance.

Results

The study was conducted on 100 obese NAFLD children (54 (54%) males and 46 (46%) females). The same number of obese children with no NAFLD (65 (65%) males and 35 (35%) females) served as the control group. Their demographic, clinical, and laboratory data are illustrated in Table 1.

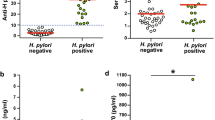

The present study showed that NAFLD children had statistically high (BMI, waist, SBP, DBP) percentiles, ALT, AST, GGT, TG, TC, and Homa IR. Also, it revealed that NAFLD children had statistically low HDL-C. NAFLD cases had a statistically increased H. pylori-positive infection (64% versus 25% in non-NAFLD subjects, p-value < 0.001). As regards H. pylori virulence factors, Cag A and Vac A positivity were statistically exhibited in the NAFLD group (34%, 10%) than in the non-NAFLD group (2%, 0%), respectively, with p-value < 0.05. Regarding NAFLD grading by ultrasound, 48% of the cases had grade 1, 31% had grade 2, and 21% had grade 3 fatty liver. There were no significant differences between NAFLD and non-NAFLD children regarding socioeconomic status (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the risk factors predicting NAFLD. Waist percentile, TG, Homa IR, and H pylori positivity were positive independent predictors for NAFLD after multivariate analysis. The overall model showed that 88.7% of NAFLD could be predicted by the significant factors in the model (R2 = 0.887).

Table 3 compares the studied parameters of NAFLD cases and NAFLD grades by ultrasound. It showed that high (BMI, waist, SBP, DBP) percentiles, ALT, GGT, TG, Homa IR, and low HDL-C were significantly associated with higher NAFLD grades. In children with H. pylori-positive infection, Cag A positivity had the highest prevalence among cases with grade 2 fatty liver.

Table 4 showed an ordinal logistic regression analysis to assess NAFLD parameters and their relation to NAFLD grades by ultrasound (using parameters that have significant differences when compared regarding NAFLD grades, as shown in Table 3). It showed that high waist percentile, DBP percentile, TG, and Homa IR were associated with higher NAFLD grades. Cag A positivity was associated with higher NAFLD grade (grade 2 fatty liver).

Discussion

NAFLD is a growing health problem in children due to increasing obesity concerns and excess consumption of fructose [1]. With increasing NAFLD severity, hepatocyte injury can lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis. H. pylori is the most common organism infecting the gastrointestinal tract. Its prevalence in developed countries reaches around 20%, but in developing countries, it reaches up to 70% [21]. Recently, an association has emerged between NAFLD and H. pylori infection with a possible causal link between them. Furthermore, H. pylori infection could exacerbate NAFLD. This is explained by the effect of H. pylori in causing low-grade systemic inflammation and releasing inflammatory cytokines, which further affect lipid metabolism, cause gut dysbiosis, alter the intestinal barrier, and promote insulin resistance. Another mechanism is that cells infected with H. pylori may release extracellular vesicles, and H. pylori can release outer membrane vesicles, which can directly impact the liver and contribute to the progression of NAFLD [22]. Also, previous studies reported that H. pylori infection could be detected in the liver tissue of NAFLD subjects [6].

To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies done on pediatrics. So, the current study investigated H. pylori infection in children suffering from NAFLD and its effect on NAFLD grades.

The present study showed an increased H. pylori infection prevalence in children suffering from NAFLD (64% of NAFLD children versus 25% of children with no NAFLD). Khalil AE et al. [23] reported 70% in NAFLD cases versus 30% in controls and Mostafa NR et al. [8] (68% versus 32% in non-NAFLD subjects).

In the current study, H. pylori infection was an independent predictor of NAFLD (OR 95% CI 5.021 (1.105–22.815)). A similar result was observed by Yan P et al. [24] (95% CI 1.02–1.79, OR 1.35, p = 0.036), Sumida Y et al. [25] (95% CI 1.111–7.644, OR 2.915, p = 0.03), and Mostafa NR et al. [8] (95% CI 1.967–16.130, OR 5.632, p = 0.001). This finding might have implications for both clinical practices such as screening and management strategies.

The results of the current study are not consistent with Valadares EC et al. [26] Variations in study designs, participant characteristics, geographic locations, and methodologies could contribute to conflicting results across different studies.

Cag A and Vac A are the main virulence of H. pylori pathogenicity. Cag A positive stains are more motile and capable of producing inflammatory cytokines, causing gut dysbiosis and increasing gut permeability [27, 28]. Also, studies showed that H. pylori could enter and stay in the hepatocytes which is mainly dependent on Cag A and Vac A status [6].

The current study showed increased Cag A and Vac A prevalence among NAFLD versus non-NAFLD children (34% versus 2% for Cag A and 10% versus 0.00% for Vac A, p-value < 0.001, 0.036, respectively).

Similar results were reported by Alvarez C et al. [29]who reported that Cag A and Vac A positivity were associated with a two-to-three-times increase in NAFLD prevalence (OR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.05–4.58 for Vac A and OR = 2.73, 95% CI 1.03–7.20 for Cag A).

The current study reported Cag A positivity was associated with high NAFLD grade (grade 2 fatty liver) (OR = 2.740 (95% CI, 1.013–7.411), p-value 0.047). Barreyro FJ et al. [30] studied the relationship between Cag A strain and NAFLD. They reported higher AST and FIB-4 values in cases with Cag A positive H. pylori infection. Contradictory to the results of the current study, Kang SJ et al. [31] reported that NAFLD was associated with Cag A negative H. pylori infection.

The current study showed that BMI, WC, blood pressure, liver enzymes, lipid profile, and Homa IR were higher significantly in children suffering from NAFLD. Khalil AE et al. [23] reported higher BMI and lipid profile in NAFLD subjects. Jin R et al. [32] reported higher BMI, ALT, AST, total cholesterol, and Homa IR in NAFLD children. Mostafa NR et al. [8] found higher BMI in NAFLD cases, but in contrast to the present study, they did not report a significant difference regarding liver enzymes and lipid profile compared to non-NAFLD cases.

In the current study, although the median of ALT and AST showed significant differences between NAFLD and non-NAFLD children, it was generally within the normal limit (30 vs. 16, 29 vs. 23 U/L, p = 0.001), respectively. Similarly, Yavuz Özer et al. [33] in their study on 155 obese children (6–18 years) reported that the median ALT and AST in NAFLD and non-NAFLD children were 28 vs. 17 and 25 vs. 19 U/L, p = 0.001, respectively. A previous study concluded that normal ALT does not exclude NAFLD [34].

The primary type of fat that builds up in the liver of individuals with NAFLD is triglyceride (TG). Triglyceride accumulation in the liver could be a cause (through direct effect or accumulation of lipotoxin) or a consequence of hepatic steatosis through hepatotoxin-mediated injury [35]. The current study revealed that TG was an independent predictor of NAFLD (OR = 1.029, 95% CI: 1.012–1.047). This was agreed by previous research [36, 37].

The current study has points of strength, and it investigated the link between H. pylori infection and NAFLD in children despite that previous studies were done on adults. Also, it studied the association between H. pylori virulence factors and their relationship to NAFLD grades.

The limitation of the current study

- It is a single-center study.

- Liver biopsy is the gold standard in NAFLD diagnosis. However, being an invasive maneuver and it is not ethical to be performed in asymptomatic children. So, abdominal ultrasound was used to detect NAFLD. To eliminate interobserver variability, it was done by a single expert radiologist.

-Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was not done after detection of H. pylori positivity by stool antigen because it is not ethical to be performed in asymptomatic children.

Conclusion

Helicobacter pylori infection could increase the risk of NAFLD in children. Further multicenter research is needed for a better understanding of the potential relationship between H. pylori and NAFLD and its broader implications taking into consideration other confounders for H. pylori infection. Furthermore, triglycerides, waist circumference, and Homa IR are significant independent predictors of NAFLD.

Data availability

Data will be available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine-aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate-aminotransferase

- AUCH:

-

Alexandria University Children’s Hospital

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Cag A:

-

Cytotoxin-associated gene A

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

- GGT:

-

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- Gro EL:

-

Chaperonin Gro EL

- HCPC:

-

Helicobacter cysteine-rich protein C

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Homa IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- H. pylori :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- Ure A:

-

Urease subunit A

- Vac A:

-

Vacuolating cytotoxin A

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Clemente MG, Mandato C, Poeta M et al (2016) Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: recent solutions, unresolved issues, and future research directions. World J Gastroenterol 22:8078

Alkassabany YM, Farghaly AG, El-Ghitany EM (2014) Prevalence, risk factors, and predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among schoolchildren: a hospital-based study in Alexandria Egypt. Arab J Gastroenterol 15:76–81

Tokushige K, Ikejima K, Ono M et al (2021) Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. Hepatol Res 51:1013–1025

Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA (2016) The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 65:1038–1048

Mavilia-Scranton MG, Wu GY, Dharan M (2023) Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on the pathogenesis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol 11:670

Ito K, Yamaoka Y, Ota H et al (2008) Adherence, internalization, and persistence of Helicobacter pylori in hepatocytes. Dig Dis Sci 53:2541–2549

Dean AG, Arner TG, Sunki GG, et al (2011) Epi InfoTM, a database and statistics program for public health professionals. CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA, www.cdc.gov/epiinfo (accessed 27 August 2024)

Mostafa NR, Ali AAM, Alkaphoury MG, et al (2023) Helicobacter pylori infection and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Is there a relationship?. Healthc Low Resour Setting. https://doi.org/10.4081/hls.2023.11379

Abdelmonem M, Elshamsy M, Wasim H, et al (2020) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Delta Egypt. Am J Clin Pathol 154:S130-S

Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE et al (2017) NASPGHAN clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 64:319–334

Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Khiyami A et al (2009) Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 51:1061–1067

El-Gilany A, El-Wehady A, El-Wasify M (2012) Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean Health J 18. https://doi.org/10.26719/2012.18.9.962

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM et al (2017) Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 140(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1904

Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Gu Q, Afful J, Ogden CL (2021) Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2015-2018. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3(46). Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/100478/cdc_100478_DS1.pdf

Koletzko S, Konstantopoulos N, Bosman D et al (2003) Evaluation of a novel monoclonal enzyme immunoassay for detection of Helicobacter pylori antigen in stool from children. Gut 52:804–806

Rosenberg W, Badrick T, Tanwar S (2017) Liver disease. In: Rifai N, Horvath AR, Wittwer CT (eds) Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 1348–1397

Remaley AT, Dayspring TD, Warnick GR (2017) Lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and other cardiovascular risk factors. In: Rifai N, Horvath AR, Wittwer CT (eds) Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 539–603

Sacks DB (2017) Carbohydrates. In: Rifai N, Horvath AR, Wittwer CT (eds) Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 518–538

Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR (2004) Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 27:1487–1495

Formichella L, Romberg L, Bolz C et al (2013) A novel line immunoassay based on recombinant virulence factors enables highly specific and sensitive serologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:1703–1710

Adenote A, Dumic I, Madrid C et al (2021) NAFLD and infection, a nuanced relationship. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021:5556354

Chen X, Peng R, Peng D et al (2023) An update: is there a relationship between H. pylori infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? Why is this subject of interest? Front Cell Infect Microbiol 13:1282956

Khalil AE, Lashin HE, Metwally MM et al (2019) A study of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Egypt J Hosp Med 77:4855–4860

Yan P, Yu B, Li M et al (2021) Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and infection in Dali City China. Saudi Med J 42:735

Sumida Y, Kanemasa K, Imai S et al (2015) Helicobacter pylori infection might have a potential role in hepatocyte ballooning in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol 50:996–1004

Valadares EC, Gestic MA, Utrini MP et al (2023) Is Helicobacter pylori infection associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals undergoing bariatric surgery? Cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J 141:e2022517

Baj J, Forma A, Sitarz M et al (2021) Helicobacter pylori virulence factors—mechanisms of bacterial pathogenicity in the gastric microenvironment. Cells 10:27

Jones TA, Hernandez DZ, Wong ZC et al (2017) The bacterial virulence factor CagA induces microbial dysbiosis that contributes to excessive epithelial cell proliferation in the Drosophila gut. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006631

Alvarez CS, Florio AA, Butt J et al (2020) Associations between Helicobacter pylori with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and other metabolic conditions in Guatemala. Helicobacter 25:e12756

Barreyro FJ, Sanchez N, Caronia V et al (2022) S1234 Helicobacter pylori infection and Cag-A strain are associated with NAFLD severity. Am J Gastroenterol 117:e892–e893

Kang SJ, Kim HJ, Kim D et al (2018) Association between cagA negative Helicobacter pylori status and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among adults in the United States. PLoS ONE 13:e0202325

Jin R, Le NA, Liu S et al (2012) Children with NAFLD are more sensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of fructose beverages than children without NAFLD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E1088–E1098

Özer Y, Yapar GC (2024) Predictors of pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in obese children and adolescents: is serum ALT level sufficient in detecting NAFLD? Zeynep Kamil Med J 55:59–66

Manco M, Alisi A, Nobili V (2008) Risk of severe liver disease in NAFLD with normal ALT levels: a pediatric report. Hepatology 48:2087–2088

Semova I, Biddinger SB (2021) Triglycerides in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: guilty until proven innocent. Trends Pharmacol Sci 42:183–190

Putri RR, Casswall T, Hagman E (2022) Risk and protective factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in paediatric obesity: a nationwide nested case–control study. Clin Obes 12:e12502

Kim A, Yang HR, Cho JM et al (2020) A nomogram for predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 23:276

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the technical staff of Alexandria University Children's Hospital for withdrawing the laboratory investigations.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. and M.A.F. described the main idea, developed a study design, and conducted data analysis. B.E. and A.M. collected the cases, performed the requested examinations, and wrote the main manuscript. O.S. and M.E.S. conducted the laboratory and radiological investigations with result supervision. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine – Alexandria University (17/11/2022) in accordance with ICH GCP (International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice) guidelines with registry number 0201736.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barakat, S., Abdel-Fadeel, M., Sharaki, O. et al. Is Helicobacter pylori infection a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children?. Eur J Pediatr 184, 47 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05867-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05867-y