Abstract

Purpose

Assessing differences between lived experiences of people affected by cancer internationally facilitates direction of international health policies and standards. The study piloted, on behalf of the World Health Organization (WHO), a global survey assessing the lived experience of people affected by cancer. We aimed to determine (1) the acceptability of the survey and (2) the survey’s capacity to capture a globally representative sample of people diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

The cross-sectional survey went through two pilot rounds. We (1) solicited feedback from international cancer organisations through a feedback form, and (2) launched a global online survey, requesting open-ended feedback on the survey format/content from people diagnosed with cancer, their family members/caregivers, and bereaved family members.

Results

Round one: 23 stakeholders found the survey acceptable in length/content. Minor suggestions were to improve readability/applicability across healthcare settings. Round two: 505 individuals participated: 177 (35%) provided feedback on the study design (e.g. to include people currently being treated for cancer, and siblings) or survey (e.g. assessing impacts of multiple cancers). Participants seemed to value the opportunity to share their experiences: “Thanks…felt good to answer as if someone was listening.” Compared with global statistics, our sample of people diagnosed with cancer (N = 240) included significantly more females (p < 0.001) and individuals from high-income countries (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Participant feedback informed important changes to the survey design and content. Our findings highlight that engaging with people with lived experience is a critical first step to develop such a global survey, optimise participation, and amplify individuals’ voices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global incidence of cancer now exceeds 19 million people per year [1,2,3]. While significant treatment advances in the last two decades have contributed to rising survival rates (now over 70% in many high-income countries, HIC), cancer also accounts for nearly 10 million deaths globally each year [1, 3]. Behind these numbers are individuals, families, and communities experiencing cancer, caring for a loved one with cancer, or grieving the loss of a loved one to cancer. Most research focused on understanding the lived experience of people affected by cancer has been limited to studies conducted in individual HICs, with questions focusing on country-specific healthcare experiences, especially around clinical processes, of people diagnosed with cancer themselves. Although these population-level studies provided novel and impactful insights into the determinants of cancer care experiences in these HICs, such studies have, to-date, lacked representation of the quality of life outcomes or lived experiences of people affected by cancer, including family members of those diagnosed, across low-, middle-, and high-income countries [4,5,6,7]. We therefore lack a global perspective on people’s lived experience, particularly in the areas of social, emotional, and financial well-being, which are negatively impacted for people with cancer and their family members/caregivers, and associated with unmet need [4,5,6, 8, 9].

The ‘lived experience of people affected by cancer’ is defined here as the experience of living with, or having lived with cancer, including but not limited to the experience of receiving treatment for cancer. It also includes supporting a loved one through cancer, both during cancer treatment and in the long-term, after treatment has finished or after a loved one has died. Conducting a global study on the lived experience of people impacted by cancer provides an invaluable opportunity to assess differences between lived experiences in high- and low-income settings, with potential to direct health policies relating to cancer care globally, identify opportunities for improvement in international standards for cancer care, and improve health equity among those affected by cancer. These are primary priorities for the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases 2013–2020 [10] and the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [11].

The World Health Organization (WHO), alongside key partners, therefore commenced a program of work aiming to better understand the immediate and long-term social, emotional, and financial impact of cancer on people diagnosed with cancer at any age, their family members and caregivers, and the family members of those who have died from cancer, in both HICs and low-middle income countries (LMICs) [12]. The program is part of a WHO campaign for the Meaningful Engagement of People Living with Non-communicable Diseases [13]. The first step in this program of work was the development of a global research survey to understand the lived experiences of people affected by cancer, with particular focus on their psychosocial and financial well-being.

Increasing evidence suggests that engaging with people with lived experience of illness to understand their perspectives on the feasibility and acceptability of a research survey is critical to ensuring the survey’s relevance, readability, and understandability for future participants [14]. Therefore, prior to full launch of the WHO survey, we piloted the survey in two stages, to seek feedback from stakeholders and people with lived experience of cancer themselves, or as family members of people diagnosed with cancer. The primary aim of this pilot was to assess the acceptability of the survey, from the perspectives of people affected by cancer around the world (Aim 1), as well as to achieve broad representation of people diagnosed with cancer across sex, cancer type, and country income level (high, middle, or low, according to World Bank country income classifications) (Aim 2) [15].

Methods

Design

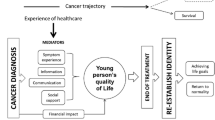

This global, cross-sectional, survey was developed in collaboration between the WHO and a steering committee comprising three cancer physicians, three psycho-oncology researchers (one of whom had a lived experience of a childhood cancer diagnosis and two of whom had lived experience of caring for a family member with cancer), one statistician, one parent of a childhood cancer survivor, and one childhood cancer survivor. The measures included in the survey are described in Table 1 [12]. The questionnaire domains were chosen using the WHO Quality of Life Framework [16], together with a literature review and steering committee consensus. We also consulted with WHO leaders from the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer to ensure alignment of the survey with the campaign for the Meaningful Engagement of People Living with Non-communicable Diseases [13]. The survey includes validated measures and open-ended questions assessing individuals’ clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as their social, emotional, and financial well-being. The survey was developed in English and translated into French and Spanish by the research team. The survey was approved by the WHO Ethics Review Committee and deemed exempt from formal review given its low-risk nature. The survey went through three phases of change: pilot round one, pilot round two, and final adaptation based on pilot feedback (Fig. 1).

Aim 1: assess the acceptability of the survey, from the perspectives of people affected by cancer around the world

Pilot round one

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

The steering committee developed a list of stakeholders representing people affected by cancer from organisations around the world, aiming to obtain feedback from a range of countries, roles (survivors and family members), and professions (researchers, medical and allied health clinicians). Stakeholders were required to be over the age of 18 and were emailed an invitation to provide feedback on the survey from a member of the steering committee who was familiar with or already connected to them professionally. Following consent, stakeholders were emailed a Microsoft Word copy of the survey. All invited stakeholders were English speakers, although not all from English-speaking countries, who reviewed the English version of the survey.

Measures

We requested feedback on the feasibility and acceptability of the survey through a brief set of questions. Feasibility questions asked participants to rate on a scale of 1–5 (‘very easy’ to ‘very difficult’) how difficult it would be to complete the survey. Further questions asked about the acceptability of the survey length, suggestions for improving the survey (e.g. addition of missing topics), and research questions of interest for stakeholders (e.g. understanding differences in fertility information provision and care internationally).

Analysis

All feedback was analysed using NVivo software [17]. Participants’ responses were grouped using inductive content analysis [18] that formed categories based on (1) the feasibility question scale and (2) suggestions to improve the acceptability of the survey. Inductive content analysis involves using pre-determined categories to code and organise the data [18], which facilitates understanding of both the types of feedback and the quantity of each type of feedback.

Pilot round two

Design

Based on pilot round one feedback, revisions were made to the survey. An online version of the survey was built using LimeSurvey software [19] and hosted online by WHO. The survey remained live from October 18, 2022, to September 30, 2023.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

Participants were recruited internationally through a combination of convenience and snowball sampling, via WHO networks, project stakeholders, and organisations who participated in pilot round one. We disseminated the survey in English, French, and Spanish, via press release by WHO Headquarters, to all member countries and regions [20]. Eligible participants were also recruited by (1) direct email invitation sent from the steering committee, (2) email invitation through a WHO network, project stakeholder, or partner organisation, or (3) accessing the survey directly through the WHO website.

Eligible participants included those who were over the age of 18 and (1) had been diagnosed with cancer (in childhood or adulthood) and finished cancer treatment, or (2) were a family member (spouse, parent, child, sibling, or other primary caregiver) of a person diagnosed with cancer and who had finished cancer treatment, or (3) were a family member (spouse, parent, child, sibling, or other primary caregiver) of a person who had died from cancer. Children or siblings under the age of 18 and people currently receiving cancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy, radiation therapy, stem cell therapy) were excluded from this pilot.

Measures

To assess the acceptability of the survey from participants’ perspectives, we obtained feedback through a free-text box in which participants could provide comments and suggestions, which asked: “You have now come to the end of the survey. We would appreciate learning about any concerns (e.g. question wording) that you may have, or points of clarification you would like to make about your responses to specific items (e.g. if the response options didn’t seem to “fit” your experience). Also, please let us know if there were topics you thought should be covered but were not. Any other feedback is welcome, as well.”

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data obtained from the open-ended questions was analysed using deductive content analysis, which involves forming categories directly out of the data, in NVivo software [17, 18]. CS and JC each independently coded the feedback to derive categories, then discussed any discrepancies to define a final list of categories, and JC re-coded the data, where needed, into the final list of categories. Categories were included if two or more participants provided the same kind of feedback.

Revision

Revision of the survey according to pilot feedback involved tabulating all qualitative feedback from the pilot rounds and making changes accordingly.

Aim 2: achieve broad representation of people diagnosed with cancer across sex, cancer type, and country income level (high, middle, or low, according to World Bank country income classifications)

Descriptive statistics were computed to characterise participant demographics, including age, sex, and residential country. Similarity of the sample relative to international cancer normative data was assessed by comparing the data on cancer survivors from our sample to data from the 2022 Global Cancer Statistics [3], across sex, country income level, continent, and cancer type (haematological, solid tumour, or central nervous system tumour) using chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests.

Results

Aim 1: acceptability of the survey from the perspective of people affected by cancer internationally

Pilot round one

An email requesting feedback on the feasibility and acceptability of the survey was sent to 33 stakeholders who spoke English and could review the English version of the survey. A total of 23 stakeholders from across HIC and LMIC completed the survey: including 3 from low-income, 7 from middle-income, and 13 from high-income countries. Stakeholders included 9 cancer survivors, 9 clinicians and/or researchers (including 5 psychologists, 2 public health researchers, and 1 nurse), 3 cancer advocates (health administration or non-profit organisation professionals) without direct relation to someone who had cancer, 2 caregivers of cancer survivors, and 1 cancer survivor who is also a bereaved caregiver of someone who died from cancer. In terms of representation across WHO regions, 3 stakeholders were from the African Region, 12 from the Americas, 4 from Europe, 1 from the Eastern Mediterranean, and 3 from the Western Pacific. No stakeholders were from the South-East Asian Region.

Feedback was generally positive, with more than half of stakeholders (n = 14, 61%) reporting the survey length was appropriate and most (n = 19, 83%) reporting there were no topics missing. However, 11 (48%) reported it would be “somewhat difficult” or “extremely difficult” to complete the survey, while 8 (35%) reported it would be “somewhat easy” or “neither easy nor difficult”. All 23 stakeholders provided one or more suggestions for improving the survey. These included improving the readability and international applicability of the survey questions, recommending simplification of wording and removal of any medical jargon, and removal of questions about survivorship care plans as models of survivorship care are too variable internationally.

Survey revision: pilot round 1

Based on the feedback from pilot round 1, the survey was adapted, with some items removed, others added, and some questions being reformulated. Specific changes to survey items as well as the addition of items in response to the feedback described are summarised in Table 2.

Items that were removed to improve the flow, reduce the length of the survey, and ensure applicability to all healthcare contexts included: items on the perceived quality of care and support received during and after treatment, specific items on family members’ cancer treatment, and some caregiving questions. Questions relating to survivorship care and feelings experienced by survivors in this regard as well as some of the perceived professional qualities in follow-up care were also removed, given the variability of access to survivorship care globally. Changes were made to language to simplify or define medical terminology (e.g.: “metastatic”, “hereditary cancer syndrome”, definitions of certain medical specialists).

Pilot round two

We received responses from 607 individuals, but excluded responses that were entirely incomplete (i.e. blank, n = 100) or appeared suspicious with odd language/statements (i.e. incoherent text, content not related to cancer or the survey; n = 2). This resulted in a total of 505 responses included for analysis. Given the anonymous nature of the survey, we were not able to verify individuals’ identities or responses.

Participant characteristics

Of the 505 included responses, participants were primarily female (419/505, 83%), identified as being a cancer survivor (301/505, 60%), and spoke English as a first language (379/505, 75%) (Table 2). Of the 301 who identified as a cancer survivor, 240 chose to respond to the survey as a cancer survivor and 61 chose to respond to the survey as a family member of someone who had cancer. Most participants were from high-income, English-speaking countries (368/505, 73%) (Table 3).

Free-text feedback on the survey

Feedback was provided by 177/505 (35%) participants, while 333/505 (66%) left the feedback field blank or indicated N/A in the feedback field, and 5/505 (0.9%) indicated that they were happy with the survey as it was. Categories derived from review of the feedback are described in Table 4. Of the 177 participants who entered a response, 112 (112/177, 63%) provided more general comments relating to their personal lived experiences of cancer not applicable to the survey. Sixty-five participants (65/177; 38%) provided feedback on the survey itself, which we were able to use to directly inform improvements to the survey content and flow.

Most participants in pilot round 2 did not provide feedback, or indicated they were happy with the survey as it was (Table 4), sharing statements such as “Thanks for the questions. Felt good to answer as if someone was listening.” Constructive feedback in pilot round 2 centred around aspects of lived experiences that the survey did not account for, such as impacts of cancer on employment, responses based on different or multiple cancer experiences, impact of childhood cancer on siblings, and experiences of people living with metastatic or advanced cancer where treatment status as identification as a “survivor” may be less clear. For example, a parent of a childhood cancer survivor shared the challenging impact of the death of their child with cancer, on their sibling: “My child who is living has suffered from extreme anxiety, PTSD, and lots of issues as a result of the death of her younger sister…I wasn’t prepared for the amount of trauma that she had endured.” And a person living with metastatic cancer shared: “I hope that WHO might consider including the needs of people with metastatic or advanced cancer…who are now living much longer with what remains an incurable cancer.” Other perspectives participants felt were missing included recent versus long ago loss of a family member, change in marital relationships over time, impact of other chronic illnesses on the cancer experience, impact of mental health conditions on people’s long-term lived experience, and how responses to certain questions may change over time. Technical feedback was provided by a subset of participants as well (30/505, 6%), including requests for improvement to response layouts and survey flow (grouping of similar types of questions).

While we collated and considered all suggested additional topic areas, we did not include some topics in the final version of the survey because they were not aligned with the study focus, or they would significantly increase the survey length. Additionally, following pilot round two, the research team was contacted directly by more than 10 cancer organisations and partners, requesting that people currently living with cancer and their family members be included, to capture their voices and experiences. Together, these challenges required revision to our study design across recruitment approaches, stakeholder engagement, and accessibility of the survey (Table 5).

Aim 2: achieve broad representation of people diagnosed with cancer across sex, cancer type, and country income level (high, middle, or low, according to World Bank country income classifications)

Compared with international normative data on people with cancer [3], our sample of 240 cancer survivors included significantly more females (83% in our sample compared to 48% internationally, X2 (1) = 71.3, p < 0.001), a higher proportion of individuals from high-income countries (88% vs. 21%, X2 (1) = 47.1, p < 0.001), and a higher proportion of individuals from the Americas (40% vs. 13%, X2 (1) = 151, p < 0.001). Our sample included significantly fewer survivors with a solid tumour diagnosis (69% vs. 80%, X2 (1) = 17.6, p < 0.001) and more survivors with a haematological diagnosis (leukaemia, lymphoma, or myeloma) (18% vs. 6.1%, X2 (1) = 64, p < 0.001). However, the proportion of CNS tumour diagnosis (1.2% vs. 1.6%, X2 (1) = 2.28, p = 0.13) in our sample did not significantly differ from international data.

Discussion

This novel, global study was initially piloted with 23 stakeholders, the first version of the survey yielded generally positive feedback, with most participants (> 60%) finding the length and content of the survey acceptable. Their suggestions for improvement centred around simplifying the wording of the survey to limit medical jargon and improve its readability. Following these revisions, the second pilot yielded similarly positive results with most participants (57%) leaving the feedback field blank or sharing positive feedback indicating that they were satisfied with the survey length, content, and flow (8%). Constructive feedback was provided by a subset of participants (13%) through which they requested inclusion of additional aspects of lived experience (e.g. mental health, employment, other illnesses, multiple cancers, death due to cancer disease versus cancer treatment), as well as technical improvements to response layouts and survey flow. Participant demographics and feedback informed further study design changes, such as inclusion of people currently being treated for cancer and targeted approaches to more effectively recruit from LMIC. These adjustments aim to ensure that future participants, regardless of their location or background, feel seen and understood.

Limitations

The representativeness of the sample of participants who completed the survey was limited. Input from males and individuals from LMICs was limited. The voices heard were predominantly those of females from high-income, English-speaking countries, which highlighted a gap we are keen to bridge in future survey efforts. These limitations are likely due to the limited availability of the survey in English, French, and Spanish, and the limited nature of dissemination pathways for the survey. Dissemination of the survey was conducted through WHO social media channels and the WHO website, as well as convenience sampling through a limited number of cancer organisations known well by the research team. No targeted or tailored dissemination of the survey in LMIC was conducted. This likely skewed our findings, contributing to the significant differences we found between people diagnosed with cancer in our study population and global statistics. Based on our snowball/convenience sampling approach, there is also likely response bias, and we cannot know who chose not to review/participate in the survey. This issue was likely exacerbated by the languages in which it was provided, as evidenced by lack of participation from people in LMICs and the predominance of participants from English-speaking backgrounds and countries. This limited the generalisability of our results and highlighted a need for us to translate the survey across additional languages, beyond English, French, and Spanish. Furthermore, these results prompted us to identify dissemination pathways in LMICs, to ensure the survey reaches these individuals whose voices are typically least heard in cancer research.

Consistent with existing research on the value of engaging people with lived experience in research study design [14], our engagement with people diagnosed with cancer, or their family members, has proven to be extremely valuable. Lived experience feedback has provided us direction to improve the survey’s acceptability and capture a wider range of experiences, across more sex/gender identities, from a more diverse set of countries and cultures, and in more languages. This pilot was a critical first step in understanding how we can optimise the launch of and participation in this kind of global study in the future.

Future directions

By revising the survey, translating it into additional languages, and creating a dissemination plan that involves a communication package and dissemination committee of stakeholders from across high-, middle-, and low-income countries, we aim to tailor and target dissemination of the survey, and to further improve the reach and acceptability of this global survey to assess the lived experience of people affected by cancer. Use of probability-based sampling, although more time and resource intensive, along with dissemination committee, may support improvement of the representativeness of the sample collected through this kind of global study in the future.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sung H et al (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249

Ferlay J, EM, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M et al (2020) Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available from:https://gco.iarc.fr/today.Accessed 2024 February 21

Bray F et al (2024) Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin 74(3):229–263

Wang AW-T et al (2023) Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the unmet needs of cancer patients and family caregivers: global psycho-oncology investigation. Support Care Cancer 31(1):36

Pramesh CS et al (2022) Priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries: a global perspective. Nat Med 28(4):649–657

Girgis A, Butow P (2009) Cancer survivorship: research priorities at the national and international levels. Cancer Forum 33(3):196–199

Alessy SA, Alhajji M, Rawlinson J, Baker M, Davies EA (2022) Factors influencing cancer patients’ experiences of care in the USA, United Kingdom, and Canada: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 47

Schilstra CE et al (2022) “We have all this knowledge to give, so use us as a resource”: partnering with adolescent and young adult cancer survivors to determine consumer-led research priorities. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 11(2):211–222

Moten A et al (2014) Redefining global health priorities: improving cancer care in developing settings. J Glob Health 4(1):010304

World Health Organization (2013) Global action plan for noncommunicable diseases. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236. Accessed 2024 May 6

United Nations (2024) Sustainable development goals. Available fromhttps://sdgs.un.org/goals.Accessed 2024 March

Cayrol J et al (2024) The lived experience of people affected by cancer: a global cross-sectional survey protocol. PLoS ONE 19(2):e0294492

World Health Organization (2023) WHO framework for meaningful engagement of people living with noncommunicable diseases, and mental health and neurological conditions. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073074. Accessed 2024 May 6

Wiles LK et al (2022) Consumer engagement in health care policy, research and services: a systematic review and meta-analysis of methods and effects. PLoS ONE 17(1):e0261808

World Bank (2024) The world by income. Available from: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html.Accessed 2024 March

World Health Organization (2012) The World Health Organisation quality of life. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol. Accessed 2024 May 6

Lumivero (2023) NVivo (Version 14); Available from: http://www.lumivero.com.

Mayring P (2015) Qualitative content analysis: theoretical background and procedures. In: Bikner-Ahsbahs A, Knipping C, Presmeg N (eds) Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education. Advances in mathematics education. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_13

LimeSurvey (2024) LimeSurvey: an open source survey tool. Available from: http://www.limesurvey.org. Accessed 2024 March 1

World Health Organization (2024) Who we are; Available from: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/regional-offices

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the American Childhood Cancer Organization. CEW is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP2008300).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Funding for this research was provided by the American Childhood Cancer Organization. CEW is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP2008300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to project conceptualization and methodology, interpretation of the results and writing review/editing. Authors CES and JC led data curation and formal analysis. CES wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with support from JC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schilstra, C.E., Wakefield, C.E., McLoone, J. et al. Development of a World Health Organization international survey assessing the lived experience of people affected by cancer: outcomes from pilot testing, user feedback, and survey revision. Support Care Cancer 33, 445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-025-09372-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-025-09372-2