Abstract

Purpose

This scoping review aims to provide a comprehensive literature review regarding supportive care needs and related interventions for patients with pancreatic cancer and/or their informal caregivers.

Methods

Following the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis, we conducted this review. In January 2025, we searched five English databases using the keywords “pancreatic cancer,” “patients/caregivers,” “supportive care,” and “needs.” We summarized the data employing the Supportive Care Framework.

Results

Of the 4752 references identified, 43 articles were included in the review. Among the 33 descriptive studies, informational needs emerged as the most frequently reported supportive care need, identified in studies involving both patients and informal caregivers (n = 6), patients only (n = 13), and informal caregivers only (n = 5). These were followed by emotional needs (n = 4) for both patients and informal caregivers, physical needs (n = 8) for patients only, and emotional (n = 4) and practical needs (n = 4) for informal caregivers only. Psycho-educational interventions were the most frequently reported approach for addressing the needs of both patients and informal caregivers, while pain/symptom management interventions were the most frequently used to support patients alone. Four studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in outcomes for intervention groups compared to control groups.

Conclusion

Patients with pancreatic cancer and their informal caregivers experienced a spectrum of supportive care needs, particularly informational needs. Intervention strategies have been developed to address their supportive care needs, but only a few studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in outcomes. These findings advance our understanding of the supportive care needs and related interventions for patients with pancreatic cancer and/or their informal caregivers, providing a foundation for future research and targeted interventions to better address these needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) remains one of the most lethal cancers and ranks seventh among cancer-related deaths worldwide. Developed countries have a higher burden than developing countries [1]. In 2019, there were 530,297 new cases worldwide compared to 197,348 in 1990, a 168.7% increase [2]. Rates are four to five times higher in countries with a higher Human Development Index (HDI) versus lower HDI countries, with the highest incidence rates in Europe, Northern America, and Australia/New Zealand [3]. Due to its poor prognosis, pancreatic cancer accounts for almost as many deaths as cases [3]. In 2019, there were 531,107 new deaths globally, a 168.2% increase from 198,051 in 1990 [2]. Although the treatment of pancreatic cancer has improved, the overall 5-year survival rate remains just above 10% [4, 5]. A recent study reported a 2-year survival rate of 32.1%, providing a better foundation for improving the quality of life for pancreatic cancer survivors [6].

Pancreatic cancer often involves complex treatments with significant morbidity, placing a substantial burden on both patients and their informal caregivers. The diagnosis is frequently overwhelming, as the disease progresses rapidly, leaving little time for adjustment [4, 5]. As an aggressive illness, pancreatic cancer profoundly impacts a patient’s physical and emotional well-being [7]. Symptoms often emerge in advanced stages, complicating treatment efforts. Common challenges include severe pain, digestive issues, emotional distress, and debilitating treatment side effects [8]. Informal caregivers, such as family members and close friends, play a critical role in supporting patients. However, caregiving comes with considerable challenges, including emotional strain, physical exhaustion, financial hardship, social isolation, and the stress of medical decision-making [9, 10]. Ultimately, pancreatic cancer significantly affects both patients and informal caregivers, underscoring the need for robust support systems and resources. Therefore, it is essential to better understand the supportive care needs of both patients and informal caregivers to enhance treatment tolerance, compliance, and overall quality of life.

Patients with pancreatic cancer and their informal caregivers typically have supportive care needs. In a cross-sectional questionnaire survey conducted in the UK, 49% (108/221) of patients reported one or more moderate or high unmet supportive care needs, particularly prominent in the advanced stage group [6]. The psychological and physical/daily living domains had the most pressing supportive care needs, including uncertainty about the future, fears of cancer progression, and diminished daily functioning [6]. In a qualitative descriptive study, ten informal caregivers identified critical needs in supporting patients with pancreatic cancer, including psychological support (e.g., coping with impending death and loss of life), managing symptoms and side effects (e.g., pain, anorexia, weakness), daily activities (e.g., inability to work, reducing housework), and participation in decision-making [11]. Informal caregivers also needed psychological support, assistance in care activities, financial support, and improved patient communication [11]. Furthermore, a mixed-methods study involving 117 pancreatic cancer patients and informal members in the USA emphasized the crucial role of providing tailored information to meet patient/informal caregiver needs during initial diagnosis [12].

Many interventions proposed addressing the diverse supportive care needs of patients with pancreatic cancer and their informal caregivers, particularly those with advanced disease. Maltoni et al. conducted a study comparing systematic early palliative care with on-demand early palliative care in 207 outpatients with inoperable pancreatic cancer; they found that patients in the systematic early palliative care group had significantly better mean scores on the Hepatobiliary Cancer Subscale and Trial Outcome Index at 3 months compared to those in the on-demand group [13]. Tseng et al. developed the Shared Decision-Making with Oncologists and Palliative care specialists (SOP) model, based on the traditional three-talk model of shared decision-making (SDM) and the Seek participation, Help comparison, Assess values, Reach decision, Evaluate decision (SHARE) model. After implementing this model in 137 advanced pancreatic cancer patients, they noted a significant increase in patients’ willingness to receive palliative care, from 50 to 78.69% [14]. Schenker et al. evaluated early specialty physician-led palliative care for 30 advanced pancreatic cancer patients and 30 caregivers; they revealed challenges such as inconvenience, long travel times, spending too much time at the cancer center, and no perceived palliative care needs [15]. Physicians recommended integrating palliative care services within oncology clinics, tailoring services to meet patient needs, and enhancing face-to-face communication between oncologists and palliative care specialists [15].

Several published reviews have explored the supportive care needs and experiences of patients with pancreatic cancer or their informal caregivers. Scott et al. conducted a literature review highlighting the significant levels of supportive care needs among these patients. They emphasized the evolving physical and psychological needs and evaluated interventions such as integrating palliative care within oncology settings, holistic needs assessments, survivorship care plans, and educational sessions to address informational and supportive care needs [16]. However, this was not a systematic review and was over 5 years old. Chong et al. identified unmet informal caregiver needs, including better clinical communication, caregiver support, and assistance in navigating the healthcare system [9]. However, this systematic review primarily focused on unmet needs rather than comprehensive supportive care needs. Kim et al. summarized the physical, emotional, spiritual, and informational unmet needs among informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer [17]. Like Scott et al., this review was not a systematic review and focused on caring experiences rather than a comprehensive assessment of supportive care needs. In addition, these three reviews did not employ a framework to support the rationale for supportive care in patients with cancer. Collectively, these reviews underscore the gaps in understanding and addressing the supportive care needs of pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers. We conducted a scoping review using the Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care to provide a comprehensive view of the landscape of supportive care needs and related interventions [18].

Review Questions

-

1.

What are the supportive care needs of patients with pancreatic cancer and/or their informal caregivers?

-

2.

What are the related interventions to meet these supportive care needs?

Methods

We developed this scoping review following the methodology of the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis [19]. We reported it according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [20]. We registered the review protocol on the Open Science Framework (OFS) (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TK9X6).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies

The participants of the included studies (1) were humans, (2) were aged 18 or older, and (3) had a confirmed diagnosis of pancreatic cancer or were informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer.

The term “supportive care” refers to providing the necessary services for those living with or affected by cancer [18, 21]. These services aim to meet their informational, emotional, spiritual, social, or physical needs during the diagnosis, treatment, or follow-up phases. This encompasses health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation, and bereavement issues. “Needs” refers to the health services required by patients and informal caregivers and the health services that patients and informal caregivers can and will retain.

We had no restrictions on the studies’ context, including geographic location and/or specific social, cultural, or gender-based interests.

We included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies. We excluded reviews, editorials, opinion articles, guidelines, protocols, case studies, and conference abstracts.

Search Strategy

A health-sciences librarian searched for related reviews across Prospero, TRIP Database, PubMed, and OSF Registries. In January 2025, we searched five bibliographic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO. The search algorithm, developed in coordination with a health-sciences librarian, is detailed in supplementary information File 1. The search string combined keywords and subject headings related to supportive care needs among pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers. We did not restrict publication dates but limited the results to English-language publications. We did not conduct a gray literature search. We subjected the search to PRESS peer review using a modified version of the PRESS document [22] and then translated it into all included databases.

Study Selection

A health-sciences librarian exported the references from each database and imported them into Covidence. Afterward, we identified and removed duplicate records. Firstly, two reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all references with the priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the two reviewers independently reviewed the full texts of the remaining references according to the same criteria. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements.

Data Extraction and Management

Two reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies into a structured data recording form. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements when the two reviewers could not resolve the disagreements by consensus. The extracted data included first author, year of publication, country of research, study design, study setting, patient sample size, cancer stage, informal caregiver sample size, measure, intervention details (theoretical basis, components, mode, format, duration, dosage, interventionist), control group, and results.

Data Synthesis and Presentation

We synthesized the data using Fitch’s Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care [18]. The supportive care needs identified in each study were classified as physical, emotional, practical, informational, spiritual, social, psychological, and other domains. Then, we counted these supportive care needs based on their frequency of identification. We summarized the intervention strategies according to the services or activities provided. We presented the results using descriptive summaries and tables.

Results

Search Results

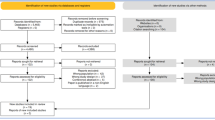

Using our search strategy, we identified 4744 references from the Cochrane Library (n = 265), PubMed (n = 2962), CINAHL (n = 493), Scopus (n = 965), and PsycINFO (n = 59). We removed duplicates automatically (n = 898) and manually (n = 15). Out of the 3831 references initially considered, we deemed 3633 references irrelevant after screening their titles and abstracts. Following full-text screening, we excluded 155 references that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, we included 43 studies. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram depicting the reference screening and selection processes.

Overview of the Included Studies

The 43 included studies spanned publication years from 2006 to 2024, with 13 conducted in the USA. Of these, 33 were descriptive studies, including qualitative (n = 19), mixed methods (n = 9), and quantitative (n = 8) designs; ten were experimental. Ten studies occurred in cancer centers or hospitals. Additionally, 20 studies included both patients with pancreatic cancer and their informal caregivers. Eleven studies had a sample size exceeding 100 patients and/or their informal caregivers. These included studies covered all cancer stages. Table 1 contains details of the included studies.

The Supportive Care Needs

We categorized the supportive care needs of pancreatic cancer patients and/or their informal caregivers based on the Fitch’s Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care (Table 2) [18]. The descriptive studies examined the needs of both patients and informal caregivers (n = 11), patients only (n = 18), and informal caregivers only (n = 9). Only one descriptive study used a theoretical framework, the Stress Process Model, to guide the selection of study variables and instruments [51].

Supportive Care Needs of Both Patients and Their Informal Caregivers

Among the studies reviewed, 11 identified supportive care needs shared by both pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Ten of these studies included both patients and informal caregivers as participants, while one study focused solely on informal caregivers to explore the supportive care needs of both patients and informal caregivers. The most frequently reported need was informational support (n = 6), encompassing concerns related to disease, medication, nutrition, self-management, symptoms, treatment options, and delivery modes. Emotional needs (n = 4) were characterized by negative emotions, such as anxiety. Physical needs (n = 3) centered on issues like nutrition, pain, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, and treatment complications. Practical needs (n = 3) included financial concerns and ethical/legal issues. Social needs (n = 2) included connections, family-related issues, and other general concerns, while spiritual needs (n = 2) focused on prayer. In contrast, psychological needs were not commonly reported in either group.

Patients’ Supportive Care Needs

Eighteen studies identified the unique supportive care needs of patients with pancreatic cancer. Of these, 14 focused exclusively on patients, three examined both patients and informal caregivers, and one explored supportive care needs solely from the perspective of informal caregivers. Informational needs were the most frequently reported (n = 13), encompassing areas such as decision-making, disease management, diet, symptom management, treatment-related issues, and delivery methods. Physical needs (n = 8) primarily involved pain, fatigue, nutrition, digestive problems, and other general health concerns. Psychological needs (n = 4) included anxiety, body image, depressive states, and sexual concerns. Emotional needs, though less frequently documented (n = 2), involved feelings of fear, shock, sadness, being overwhelmed, uncertainty, and worry. Practical needs (n = 2) centered on daily living assistance and exercise. Notably, social and spiritual needs were not identified in the reviewed studies.

Informal Caregivers’ Supportive Care Needs

Night studies examined informal caregivers’ supportive care needs, with the majority identifying informational needs (n = 5), such as caregiving and decision-making, disease management, treatment, and symptom management. Practical concerns (n = 4) were also frequently reported, including challenges related to daily life, caregiving responsibilities, training, and financial issues. Emotional needs (n = 4) encompassed fear and the need for emotional support. Physical (n = 1) and psychological needs (n = 1) focused on the physical issues and stress associated with caregiving, respectively, while spiritual needs (n = 1) highlighted informal caregivers’ search for meaning. Notably, social needs were not reported in these studies.

Interventions to Meet the Supportive Care Needs

Ten experimental studies examined the effectiveness of various interventions on the supportive care needs of patients with pancreatic cancer and/or their informal caregivers. These interventions were categorized based on the services or activities following the Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care by Fitch [18]. Among the ten experimental studies, two implemented interventions that simultaneously addressed the needs of both pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers.

Interventions Targeting Both Patients and Informal Caregivers

As presented in Table 3, the most targeted areas were psycho-educational support (n = 2), orientation/ongoing patient and family education (n = 1), adjustment/supportive counseling (n = 1), nutritional intervention (n = 1), and pain/symptom management (n = 1). One of the two studies developed interventions based on a theoretical framework and involved at least two types of professionals, such as nurses, social workers, oncologists, and dieticians (Table S2). Standard measures assessed included feasibility, distress levels (using a distress thermometer), components of intervention sessions delivered, care plans and referrals, and interviews. Interventions were delivered either in-person (n = 1) or via phone/video (n = 1), and were administered individually, to couples, or in group settings. The duration of the interventions varied, ranging from a single session to nine sessions. One study reported dosages of once per week or fortnightly, with sessions lasting between 20 and 99 min.

Interventions Targeting Patients Only

Most interventions targeting patients have focused on pain/symptom management (n = 7), followed by adjustment/supportive counseling (n = 5), orientation/ongoing patient and family education (n = 3), psycho-educational services or activities (n = 2), and practical and functional assistance (n = 2) (see Table 3). One of the eight studies developed interventions using a theoretical basis. Four studies included interventions implemented by at least two types of professionals, such as physicians, nurses, chaplains, social workers, and oncologists. Eight studies had control groups. Standard measures assessed included quality of life, symptoms, and feasibility. Notably, four of the eight studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in outcomes in intervention groups compared to control groups, as outlined in Table S2. The studies delivered the interventions in-person (n = 6) or through a hybrid approach combining in-person and phone/video methods (n = 2). Almost all interventions were delivered individually. The duration of the interventions ranged from a single session to an unlimited number of sessions until death. Most studies did not report the dosages of the interventions.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the experiences of patients and their informal caregivers throughout pancreatic cancer care, emphasizing the range of informational, emotional, physical, practical, psychological, social, and spiritual challenges [18]. The supportive care needs identified in this review align with those found in previous reviews on overall types of cancer [60, 61], suggesting that the basic standards for cancer supportive care apply to pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers [18]. Additionally, we identified a growing number of targeted interventions aimed at addressing these supportive care needs. Ongoing systematic assessment of supportive care needs and the implementation of tailored interventions remain essential to improving outcomes for both patients and their informal caregivers [18, 62].

Information is the highest reported supportive care need for pancreatic cancer patients and/or their informal caregivers. The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is often overwhelming, and the treatment is complex and intense. Therefore, information regarding the treatment plan, related side effects, and symptom management can help patients and informal caregivers regain focus and control, allowing them to better cope with and process the life-threatening diagnosis [18, 52]. Moreover, information about treatment complications, alternatives, logistics, and potential outcomes is crucial for informed decision-making [39]. This information should be provided in understandable formats, using basic language, and delivered in a timely manner [25, 31, 40].

Emotional needs are also a significant concern for both pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers [6, 12, 24, 28, 32, 51]. Among the questions posted on a pancreatic cancer website, the second most common category involved concerns about the illness and emotional issues related to pancreatic cancer [29]. Informal caregivers reported feelings of confusion, anger, sadness, and hopelessness following a loved one’s diagnosis of terminal cancer and sought guidance on coping strategies [32]. These findings highlight the need for supportive care services that address both the emotional challenges of a cancer diagnosis and the complexities of the caregiving role [12].

This review also underscores the persistence of inadequate physical symptom management throughout the cancer journey, highlighting supportive care needs for nutrition, gastrointestinal symptoms, and pain [27,28,29, 46]. The higher needs for symptom management align with the traditional approach to supportive care, emphasizing the importance of managing cancer and treatment-related symptoms [62]. Eating distress and poor food intake lead to associated weight loss, a significant prognostic indicator of survival and response to treatment [18]. Therefore, patients should consider specialized cancer treatment support services for diet and nutrition [38, 62].

Patients and informal caregivers identified practical needs, such as assistance with daily activities, financial support, and help with caregiving. This aligns with previous studies that highlighted financial needs as the most prevalent for people with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers [60]. Thus, supportive care services should include assistance with daily activities, financial services, and guidance for appropriate patient care. Similarly, psychological needs, including the ability to cope with the illness experience and its consequences, were prevalent among patients and informal caregivers [11, 27]. This study identified anxiety and depressive state as the primary psychological issues [38], indicating areas where supportive care services should focus.

The literature highlights a growing number of targeted interventions aimed at addressing the supportive care needs of pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Among interventions designed for both patients and caregivers, psycho-educational services or activities are the primary components. Beesley et al. emphasized the importance of enhancing self-efficacy for both groups [53], while Tong et al. developed a comprehensive psycho-educational intervention covering palliative care, advance care planning, the impact of cancer on patients and families, available supportive care services, nutrition, and symptom self-management [54]. However, no studies have exclusively focused on interventions tailored specifically for informal caregivers of pancreatic cancer patients, underscoring a significant gap and an opportunity for future research.

For interventions targeting patients’ needs only, the most common components focus on pain and symptom management [16]. Chung et al. explored the impact of palliative care interventions on physical and psychological symptoms, revealing a trend toward improvement in physical, social, emotional, and psychological distress and functional quality of life (QOL) subscales [56]. Other interventions involving pain/symptom management are offered alongside other services or activities, such as orientation/ongoing patient and family education [14, 15, 55], psycho-educational activities [55], adjustment/supportive counseling [13,14,15, 55, 58], and practical and functional assistance [15, 59]. The SOP model by Tseng et al. was the only pain/symptom management intervention based on theoretical frameworks, indicating a significant increase in patients’ willingness to receive palliative care from 50.00 to 78.69% after implementing the SOP model (p = 0.01) [14]. The literature review by Scott et al. also pointed out that palliation of pain and non-pain symptoms is crucial for supportive care in patients with pancreatic cancer, and early referral to palliative care and its integration within oncology may improve management [16].

This scoping review has several limitations. First, it includes only publications in English, potentially excluding relevant studies in other languages that could offer additional insights. Second, most of the included studies involved participants at various stages of cancer, making it challenging to isolate findings specific to each stage. Since supportive care needs and related interventions vary by cancer stage and treatment phase, future research should further explore these differences in pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers.

In summary, patients with pancreatic cancer and/or their informal caregivers have diverse, supportive care needs, particularly regarding information. Various intervention strategies have been implemented to address these needs, but only a few showed statistically significant outcome improvements. These findings enhance our understanding of the supportive care needs of pancreatic cancer patients and their informal caregivers, providing a basis for future healthcare practice and research.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study is included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and burden of pancreatic cancer. Presse Med. 2019;48(3 Pt 2):e113–23.

Kan C, et al. Global, regional, and National Burden of pancreatic Cancer, 1990-2019: results from the global Burden of disease study 2019. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):33.

Sung H, et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49.

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of pancreatic Cancer: global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J Oncol. 2019;10(1):10–27.

Watson EK, et al. Experiences and supportive care needs of UK patients with pancreatic cancer: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e032681.

Ibrahim AM, et al. Characterizing the physical and psychological experiences of newly diagnosed pancreatic Cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2024;25(7):2483–92.

Tang CC, Von Ah D, Fulton JS. The symptom experience of patients with advanced pancreatic Cancer: an integrative review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(1):33–44.

Chong E, et al. Systematic review of caregiver burden, unmet needs and quality-of-life among informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2022;31(1):74.

Fong ZV, et al. Assessment of Caregivers' Burden when caring for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(11):1468–75.

Ploukou S, et al. Informal caregivers' experiences of supporting patients with pancreatic cancer: a qualitative study in Greece. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;67:102419.

Hagensen A, et al. Using experience-based design to improve the care experience for patients with pancreatic Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e1035–41.

Maltoni M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:61–8.

Tseng YL, et al. Shared decision making with oncologists and palliative care specialists (SOP) model help advanced pancreatic cancer patients reaching goal concordant care: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 2023;12(19):20119–28.

Schenker Y, et al. A pilot trial of early specialty palliative Care for Patients with advanced pancreatic Cancer: challenges encountered and lessons learned. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(1):28–36.

Scott E, Jewell A. Supportive care needs of people with pancreatic cancer: a literature review. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2019;18(5):35–43.

Kim Y, Baek W. Caring experiences of family caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer: an integrative literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):3691–700.

Fitch MI. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18(1):6–24.

Aromataris E, et al. JBI manual for evidence synthesis, vol. 10. Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide; 2024.

Tricco AC, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Hui D, et al. Concepts and definitions for "supportive care," "best supportive care," "palliative care," and "hospice care" in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):659–85.

McGowan J, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Zhang B, et al. A qualitative study on the disease coping experiences of pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):18626.

Khan NN, et al. A qualitative investigation of the supportive care experiences of people living with pancreatic and oesophagogastric cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–11.

Griffioen IPM, et al. The bigger picture of shared decision making: a service design perspective using the care path of locally advanced pancreatic cancer as a case. Cancer Med. 2021;10(17):5907–16.

Okuhara T, et al. Cancer information needs according to cancer type: a content analysis of data from Japan's largest cancer information website. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:245–52.

Grant MS, Wiegand DL, Dy SM. Asking questions of a palliative care nurse practitioner on a pancreatic cancer website. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):787–93.

Gooden HM, White KJ. Pancreatic cancer and supportive care--pancreatic exocrine insufficiency negatively impacts on quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(7):1835–41.

Grant MS, Wiegand DL. Conversations with strangers. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2013;15(5):278–85.

Chapple A, Evans J, Ziebland S. An alarming prognosis: how people affected by pancreatic cancer use (and avoid) internet information. Policy Internet. 2012;4(2)

Saunders C, et al. As the bell tolls: a foundation study on pancreatic cancer consumer's research priorities. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:179.

Coleman J, et al. The effect of a frequently asked questions module on a pancreatic cancer web site patient/family chat room. Cancer Nurs. 2006;28(6):460–8.

Nolan MT, et al. Spiritual issues of family members in a pancreatic cancer chat room. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(2):239–44.

Nguyen G, et al. Supplemental tube feeding: qualitative study of patient perspectives in advanced pancreatic cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024;14(e3):e3002–10.

Gerhardt S, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a palliative care case management intervention for patients with incurable gastrointestinal cancer (PalMaGiC) in a hospital department. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;66:102409.

Marinelli V, et al. Preoperative anxiety in patients with pancreatic Cancer: what contributes to anxiety levels in patients waiting for surgical intervention. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(14):2039.

Ristau P, Oetting-Ross C, Buscher A. From surviving to living (on): a grounded theory study on coping in people with pancreatic Cancer. J Patient Exp. 2023;10:23743735231215605.

Carruba G, et al. Unmet nutritional and psychological needs of Cancer patients: an integrated multi-professional model approach. Diseases. 2022;10(3):47.

Lee HJ Jr, et al. Communicating the information needed for treatment decision making among patients with pancreatic cancer receiving Preoperative therapy. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(3):e313–24.

Stevens L, et al. Characterizing the patient experience during neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a qualitative study. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14(6):1175–86.

Mikkelsen MK, et al. Attitudes towards physical activity and exercise in older patients with advanced cancer during oncological treatment – a qualitative interview study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;41:16–23.

Almont T, et al. Sexual health and needs for sexology care in digestive cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a 4-month cross-sectional study in a French University hospital. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2889–99.

Dunleavy L, Al-Mukhtar A, Halliday V. Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy following surgery for pancreatic cancer: an exploration of patient self-management. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;26:97–103.

Sandgren A, Strang P. Palliative care needs in hospitalized cancer patients: a 5-year follow-up study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):181–6.

Beesley V, et al. Risk factors for current and future unmet supportive care needs of people with pancreatic cancer. A longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3589–99.

Cooper C, Burden ST, Molassiotis A. An explorative study of the views and experiences of food and weight loss in patients with operable pancreatic cancer perioperatively and following surgical intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1025–33.

Schildmann J, et al. 'One also needs a bit of trust in the doctor ... ': a qualitative interview study with pancreatic cancer patients about their perceptions and views on information and treatment decision-making. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2444–9.

Huynh TNT, et al. The unmet needs of pancreatic cancer carers are associated with anxiety and depression in patients and Carers. Cancers. 2023;15(22):5307.

Ruff SM, et al. Evaluating the caregiver experience during neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2024;129(4):775–84.

Ibrahim F, et al. In the shadows of patients with upper gastrointestinal Cancer: an interview study with next of kin about their experiences participating in surgical Cancer care. Clin Nurs Res. 2020;29(8):579–86.

Sherman DW, et al. A pilot study of the experience of family caregivers of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer using a mixed methods approach. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(3):385–399.e2.

Petrin K, et al. Adjusting to pancreatic cancer: perspectives from first-degree relatives. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):281–8.

Beesley VL, et al. Supporting patients and carers affected by pancreatic cancer: a feasibility study of a counselling intervention. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;46:101729.

Tong E, et al. Development of a psychoeducational intervention for people affected by pancreatic cancer. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:80.

Kim CA, et al. The impact of early palliative care on the quality of life of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the IMPERATIVE case-crossover study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(4):250.

Chung V, et al. Improving palliative care and quality of life in pancreatic cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(5):720–7.

Marinelli V, et al. PREPARE: PreoPerative anxiety REduction. One-year feasibility RCT on a brief psychological intervention for pancreatic cancer patients prior to major surgery. Front Psychol. 2020;11:362.

Maltoni M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:110–8.

Sun V, et al. Pilot study of an interdisciplinary supportive care planning intervention in pancreatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3417–24.

Hart NH, et al. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176:103728.

Evans Webb M, et al. The supportive care needs of Cancer patients: a systematic review. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(5):899–908.

Hui D, Hoge G, Bruera E. Models of supportive care in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2021;33(4):259–66.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Ms. Kim Marie Renfro at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio School of Nursing for her invaluable editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF and LS performed the study’s conceptualization and methodology. LF, SHK, DDG, ML, LRR, and MH conducted data curation and software. LF and SHK performed the formal analysis and writing of the original draft. AP and LS provided project administration, resources, supervision, validation, and visualization. CV, AP, PY, and LS provided writing-review and editing. All authors reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, L., Kim, S.H., Garcia, D.D. et al. Supportive Care Needs and Related Interventions in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer and Their Informal Caregivers: A Scoping Review. J Gastrointest Canc 56, 98 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-025-01218-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-025-01218-8

Keywords

Profiles

- Ping Yu View author profile