Abstract

Introduction

The ALLEGRO- 2b/3 (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT03732807) study demonstrated efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in patients with alopecia areata (AA). Despite clinically meaningful improvement in hair regrowth, differences in patient-reported emotional symptoms or activity limitations (subscales of the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes [AAPPO]) between treatment groups were not significant. This study aimed to identify potential factors that may impact the measurement of patient-reported outcomes in AA.

Methods

This mixed methods study conducted remote interviews with individuals with self-reported AA. Interviews were designed to understand how experiences with AA impacted study participant health-related quality of life and gain insights into how historical personal circumstances and individual characteristics might impact AAPPO responses. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic and content analytical processes; quantitative data were analyzed descriptively.

Results

Qualitative analysis of interview transcripts of 30 adults with AA (seeking or had received AA treatment) yielded three overarching themes: mechanisms of adaptation (subthemes: behavioral and mental strategies), impact changes over disease journey (subthemes: hair loss and regrowth as an event and changes in impact over time after loss and/or regrowth), and underlying characteristics that moderate adaptation. Participants reported requiring 50–100% regrowth for 6–12 months before they would provide different AAPPO emotional and activity limitation responses.

Conclusions

High levels of hair regrowth over a sustained period of time would be required to change AAPPO responses. Factors identified that may affect measurement of patient-reported psychosocial outcomes in AA included length of time since hair regrowth. Understanding factors that impact adaptation can help inform clinical practice and research.

Plain Language Summary

This study used interviews to explore the way people with alopecia areata, a disease that causes hair loss, saw their disease and what amount of hair regrowth was needed to feel less negative and not avoid activities. People with alopecia areata talked about ways they changed their behavior and thinking, how hair loss and regrowth felt, and how their personality helped their outlook. They wanted large amounts of hair regrowth for at least 6–12 months before feeling better or doing activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease leading to hair loss that is associated with reduced health-related quality of life and a substantial psychosocial burden that may be mediated by individual patient characteristics; however, such factors may be challenging to account for when using quantitative patient-reported outcome measurements alone. |

Inconsistencies suggestive of a response shift, or internal prioritization of internal standards of quality of life, can be seen between clinical efficacy and participant-reported outcome measures; qualitative interviews may help understand discrepancies between observed and expected changes in patient cognition when beginning new treatments. |

This study aimed to identify potential contributing factors that may impact the measurement of psychosocial patient-reported outcomes in patients to better understand the relationship between each patient and their AA, including a patient’s historical experiences, their current characteristics, and perceptions of hair regrowth amount and duration. |

What was learned from the study? |

Qualitative analysis of interview transcripts of 30 adults with AA (seeking or had received AA treatment) yielded three overarching themes: mechanisms of adaptation (subthemes: behavioral and mental strategies), impact changes over disease journey (subthemes: hair loss and regrowth as an event and changes in impact over time after loss and/or regrowth), and underlying characteristics that moderate adaptation; participants reported requiring 50–100% regrowth for 6–12 months before they would provide different responses to the patient-reported outcome measure. |

The core themes identified in this study provide evidence that some patients with AA may become highly adapted to their disease, and showed that participant views on hair regrowth were complex, with many participants showing evidence of a response shift. |

In order for patients with AA to consider changes to the patient-reported outcome measurement, high levels of regrowth over a sustained period of time would be required, highlighting how patients view effective treatments. |

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that has an underlying immuno-inflammatory pathogenesis and is characterized by nonscarring hair loss ranging from small patches to complete scalp, face, and/or body hair loss [1]. AA affects approximately 7 million people in the USA, with an estimated US point-prevalence of 0.21% [2]. Beyond hair loss, AA is associated with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a substantial psychosocial burden, and higher rates of depression and anxiety (compared with the general population) [3–12]. Individual patient characteristics, such as resilience, can mediate this burden, with associated improvements in perceived stress (regardless of severity of hair loss) or impact of AA on their lives [13]. However, such factors may be challenging to account for when using quantitative patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures alone.

The ALLEGRO- 2b/3 (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT03732807) study demonstrated efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in patients with AA and ≥ 50% scalp hair loss who had a median (range) duration since diagnosis of AA of 5.8–7.4 (0–53.4 and 0.3–60.1, respectively) years between treatment groups [14]. Ritlecitinib was subsequently approved in June 2023 as a treatment for patients aged ≥ 12 years with severe AA [15]. Participants in the ALLEGRO- 2b/3 clinical trial completed the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) PRO instrument during treatment. The AAPPO is a validated disease-specific, self-reported questionnaire designed to measure the impact of AA across three domains: hair loss, emotional symptoms (ES), and activity limitations (AL) [16]. Despite observing clinically meaningful improvement in hair regrowth with ritlecitinib compared with placebo up to 48 months post treatment, differences in patient-reported AAPPO ES and AL subscale scores between groups were not significant at weeks 24 and 48 [17]. This pattern was also seen in other clinical trials with the Alopecia Areata Symptom Impact Scale (AASIS) [18].

The inconsistencies between clinical efficacy and PRO responses could suggest a “response shift” in participants regarding hair loss and the HRQoL impacts of AA [16]. Response shift involves an individual changing their self-evaluation of a construct, leading to internal recalibration, reprioritization, or reconceptualization. If participants reprioritize their internal standards of HRQoL during treatment, that may lead to little-to-no changes seen on self-reported scales [19, 20]. Qualitative interviews can be used to detect response shift and may aid in understanding discrepancies between observed and expected changes in participant cognition [21].

As the primary AA disease burdens are psychosocial in nature, this study aimed to identify potential contributing factors that may impact the measurement of psychosocial PROs in patients to better understand the relationship between each patient and their AA. Specifically of interest were patient’s historical experiences, their current characteristics, and perceptions of hair regrowth amount and duration.

Methods

Study Design

This study used a mixed-methods approach to conduct semi-structured interviews and a patient-generated index task between August and October 2023.

Participant Population

Participants based in the USA with a self-reported diagnosis of AA who were English speakers and aged ≥ 18 years were eligible to participate in the study. To allow a portion of participants to offer insights based on their treatment experiences (and to increase the likelihood that these patients experienced any hair regrowth), a target of ≥ 10 patients who had previously received pharmacological treatments for AA was pursued. Additional recruitment subtargets included ≥ 8 Black and 12 male participants.

Participants provided written inform consent prior to entering the study. The study protocol and all participant-facing documentation, including the interview discussion guide, were reviewed by an independent, USA-based ethics review board (Advarra, Inc., Columbia, MD, USA), which deemed the study to be exempt from institutional review board oversight. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor, and followed generally accepted research practices described in British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association guidelines, UK Data Protection Act 2018, General Data Protection Regulation, and relevant legislations pertaining to data privacy for participants in the USA.

Interview Setting and Content

Individuals participated in single-person interviews, during which they completed the AAPPO. ES and AL items are captured on a 5-point frequency scale (always/completely, often/quite a bit, sometimes/somewhat, rarely/very little, and never/not at all). Interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer and completed in a single ≤ 60-min session via an online audio teleconference platform.

Interviews were facilitated by a discussion guide (Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix), which included: (1) questions about participant experiences with AA since diagnosis, AA symptoms, and aspects of HRQoL impacted; (2) questions exploring potential scale measurement challenges around the AAPPO ES and AL subscale items, including the amount of hair growth and amount of time with regrowth that would be needed for their response to the AAPPO ES and AL domains to improve; and (3) questions about participant clinical and demographic characteristics, including hair curl type [22].

Analyses

Qualitative data were analyzed using MaxQDA 2023 software program (VERBI Software GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Analysts independently coded transcripts by labeling and categorizing the qualitative data using descriptive titles for each code. Codes and themes were initially linked and grouped by descriptive similarity. The most prevalent and meaningful themes were then compiled.

Quantitative analysis included descriptive analyses of the AAPPO items. Continuous outcomes were summarized with means and standard deviations (SDs) or interquartile ranges.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Interviews were conducted with 30 participants who were seeking or who had received treatment for AA. Mean (SD) and median ages of participants were 46 (17) years and 26.5 years, respectively, with mean (SD) and median durations of living with AA of 14.5 (13.2) years and 10.0 years, respectively (Table 1). Overall, 17 participants (56.7%) had been diagnosed ≥ 10 years ago. The majority of participants were White (56.7%), were female (63.3%), and had type 2 hair (“wavy”; 46.7%). Recruitment subtargets were exceeded for participants who had received previous treatment (n = 23) and Black participants (n = 9). Overall, 11 participants were male (92% participant subtarget achievement).

Core Themes

Three overarching themes were identified (Table 2). The most prevalent theme of mechanisms of adaptation was separated into two subthemes specifying differences in behavioral and mental processes. The second theme of impact changes over disease journey was separated into subthemes specifying hair loss and regrowth as a discrete event and the changes in impact over time after hair loss and/or regrowth. The final theme was underlying characteristics moderating adaptation.

Mechanisms of Adaptation

Mental and Cognitive Adaptation Strategies

Mental and cognitive adaptation strategies were frequently coded concepts throughout participant interviews (83%; Table 2). Participants predominantly spoke of a positive process in which they adjusted their attitude or approach to life in the face of AA. Frequently, participants described acceptance of their condition as a sign of personal growth.

“It's been more than that in the past few years because I was mad at myself. I was mad at the whole world about my hair, but gradually I have come to accept what's going on.” (female living with AA for 1 year).

Other participants emphasized that this acceptance was not negative and that while they maintained hope for hair regrowth, they recognized that hair loss was part of their new self-identity.

“At this point, I've accepted it. I love the way I look…I go through these little interims of a little hair growth here and there. It's kind of exciting and interesting. But ultimately, I've accepted that, hey, I don't grow hair.” (male living with AA for 32 years).

Some participants spoke about conscious efforts to restructure their internal narrative about self-identity, such as challenging themselves to adopt a positive mental attitude, using humor, or finding new ways to express themselves.

“I always used to wear a hat everywhere in public. And now, I have been working on being more courageous about wearing a headband instead of a hat. So, my scalp is essentially exposed.” (female living with AA for 3 years).

“My doing very intense internal work and reframing my thoughts, rewriting the narrative and using positive affirmation.” (male living with AA for 17 years).

A minority of participants described their acceptance in a negative light, using strategies such as an increased emphasis on other areas of life. Others spoke of “giving up” in terms of looking for future treatments or attempting to “simulate…a normal person.”

“I've had to accept it over the years, and with that acceptance has come depression.” (male living with AA for 17 years).

Behavioral Strategies for Adaptation and Reducing Visibility

Participants frequently spoke about physical or behavioral strategies for coping with AA and reducing the visibility of hair loss (coded in 83% of interviews). Most of these strategies included head coverings and altering hairstyles to reduce visibility of hair loss patches. The use of head coverings when participants were in public was a strategy used to reduce self-consciousness and increase confidence.

“I would find a way to get around it. I'd put on a kerchief. I have tons of really cute hats. I would just put on a hat and show up.” (female living with AA for 3 years).

“Because she [my hairdresser] was doing such a good job and she understood…I can kind of trim the back and I can keep it straight…And when I'm doing that, sometimes I might make a little problem the way I cut it, and I'm like those are my disgusting times, it's like, ‘Why am I doing this?’” (male living with AA for 2 years).

Participants also referenced lifestyle modifications such as healthier diets, changes to sleep behaviors, and exercise.

“I can't change my head, so I can't change the way people look at my head. I might as well change the way people look at my body, so that's why I got big into fitness” (male living with AA for 16 years).

Impact Changes Over Disease Journey

Regrowth and Loss as Catalysts for Impact Shift

Hair loss was described as an event resulting in negative changes to HRQoL by 73% of participants. Immediately following hair loss, participants described greater self-consciousness and limitations in their social activities; others spoke in detail about increases in negative emotions.

“The emotions that came when I was 12 of not wanting to be seen like that, that's just carried on and it's something I've never really gotten over.” (male living with AA for 8 years).

By contrast, hair regrowth was mainly seen as a catalyst for improvement in aspects of HRQoL. Participants described feeling more comfortable, more confident, and less embarrassed when taking part in activities and interacting with others, as well as the presence of positive emotions, less worry, and less frustration.

“If I grow a couple chest hairs, I get excited because I feel like it’s a victory.” (male living with AA for 32 years).

Initial hair regrowth was also associated with uncertainty or fear whether regrowth would continue or be followed by another cycle of hair loss. Eight participants expressed that regrowth led to reduced confidence and an increase in self-consciousness because it drew further attention to the presence of AA.

“A little bit of growth, I guess, would give me some optimism and hope, but I don't know if it would resolve the self-consciousness.” (female living with AA for 10 years).

Impact Changes Over Time

Increased duration of living with AA was associated with aiding in adaptation (coded in 63% of participants); for example, participants mentioned that with increased age, hair loss is socially recognized as a norm. Time itself also gave participants increased practice in using their behavioral or mental strategies and greater experience in building resilience against negative emotions associated with AA.

“A slow adjustment over time to where it is less of an alarming kind of thing and less of a priority.” (female living with AA for 5 years).

“Because of all the experiences I've gone through with it, and how I've been able to learn more about it even though it's still very unpredictable.” (male living with AA for 16 years).

Time was also seen as helpful in reprioritizing values toward helping others, including family members and others within the AA community.

“Now I do feel comfortable about reaching out to the community because I do want to help. But when I was in need of help, I didn't reach out.” (male living with AA for 16 years).

Underlying Stable Characteristics Moderating Adaption

Participants often described stable aspects of their personalities that moderated the impact of AA and facilitated adaptation (73% of participants referred to stable characteristics). For some, this included an optimistic disposition, describing themselves as naturally resilient and confident, or prioritizing other health conditions.

“I've always been a very confident person. I'm also a very attractive person…So if my hair doesn't look good, it doesn't make me crazy.” (female living with AA for 3 years).

“I have a whole basket full of things that have affected my outlook on life that became large and came more to the forefront it [AA] kind of fell a little bit to the background.” (female living with AA for 5 years).

AAPPO Responses

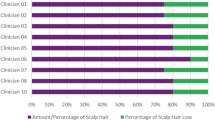

Participant responses to the AAPPO are summarized in Fig. 1. Overall, 22 participants (73%) felt self-conscious “sometimes” to “always” about their AA. Similar proportions of participants felt embarrassed, sad, or frustrated about their AA “sometimes” to “always” (13 [43%], 12 [40%], and 14 [47%] participants, respectively). Most participants reported no activity limitations, with 20 (67%), 27 (90%), and 21 (70%) participants responding “not at all” when asked if they limited outdoor activity, physical activity, and interactions with others, respectively.

Participant responses to the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) emotional symptoms and activity limitations items. Thirty participants completed the AAPPO questionnaire. No participants responded that they limited their outdoor activities, physical activities, or interactions with others “completely,” and no participants responded that they limited their physical activity “quite a bit”

Across most AAPPO items, most participants required substantial hair regrowth (50%–100%) lasting for ≥ 6–12 months before they would provide different (improved) responses to AAPPO ES and AL items (Figs. 2, 3).

How much regrowth would it take for you to answer this question differently? For the “self-conscious” emotional symptom item, no participants selected 25–49% regrowth or 50–74% regrowth. For the “sad” emotional symptom item, no participants selected 0–24% regrowth. For the “physical activity” activity limitations item, no participants selected 0–24% regrowth or 25–49% regrowth. For the “interactions with others” activity limitations item, no participants selected 25–49% regrowth

How long would regrowth need to last for you to answer this question differently? For the “self-conscious” emotional item, no participants selected 6–12 or > 12 months. For the “sad” emotional item, no participants selected > 12 months. For the “physical activity” activity limitations item, no participants selected > 12 months

Discussion

This study used a mixed-methods approach to qualitatively and quantitatively measure factors that affect psychosocial PRO responses in patients with AA. Patients used substantial behavioral and cognitive adaptations to develop resilience and cope with the impact of AA on their daily lives.

The results of this study offer insights into the challenges and confounding factors that can affect HRQoL measurements in patients with AA. Previous studies examining HRQoL in patients with AA found potential ceiling effects and a negative relationship between the emotional and social domains of the AAPPO [14, 16, 18]. Within the current study, themes of resilience and coping adaptations emerged, which can impact HRQoL, particularly in patients with long-term disease or greater hair loss [23]. These physical and mental strategies can increase baseline perceptions of health. Future studies aiming to capture the true effect of clinical efficacy on HRQoL may need to consider that patients continue to adapt to their conditions even in the absence of treatment.

Participant views on hair regrowth were complex, and many provided evidence of a response shift. Eleven participants related negative feelings associated with hair regrowth, such as feeling increased self-consciousness and fear that hair regrowth would not be sustained based on previous cycles of hair regrowth and loss. AA is a disease that often has an unpredictable clinical course of regrowth and relapse [1, 2, 24]. One prior survey reported a high prevalence of patients with AA meeting post-traumatic stress disorder screening criteria related to hair loss [25]. Given that relapse after regrowth can be more traumatic than initial hair loss, even with efficacious treatments, patients may require additional time before their perceived impacts of AA on QoL improve. In the current study, duration of living with AA varied widely. In patients who were newly diagnosed, and therefore less likely to have undergone many cycles of regrowth and loss, there may be a different relationship with their experiences of clinical efficacy and perceived improvements in HRQoL.

As the AA disease journey is nonlinear, the adaptation process is often not a continuous positive process. Within the current study, certain patients noted that their acceptance was seen negatively or described as “giving up” hope, while others referred to instances when their adaptation aids caused negative feelings. Within the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 study, while participants who received 50 mg ritlecitinib reported greater improvements in the ES and AL subscale scores after 48 weeks of treatment compared with those who received a subtherapeutic dose, differences in subscale scores between groups were not significant at weeks 24 and 48 [14]. The median duration of current episode of hair loss was 2.2–2.7 years; however, median disease durations ranged from 5.8 to 7.4 years, suggesting that patients had adapted over a longer period of time.

Participants would require high levels of scalp hair regrowth (50–100%) over a sustained period of time to change their responses to AAPPO items, highlighting for the first time how patients view effective treatments. This provides a challenge for using PRO responses in clinical trials, for which efficacy may be measured using cutoffs below this level of hair regrowth, and trial lengths are often shorter than the reported desired duration of sustained hair regrowth needed to change AAPPO responses [14, 26, 27]. Across many global studies, the rate of spontaneous remission is < 10% in patients who have greater hair loss and for those with longer episodes of hair loss [28–30]. This implies that it may take some time for patients with AA to trust that treatment will result in sustained hair regrowth. The results of the current study suggest that longer trial durations or follow-up periods extending beyond traditional efficacy endpoints would assist in fully assessing treatment efficacy and determining improvements to HRQoL. Additionally, data collection from real-world practice may aid in assessing changes over longer periods of time.

At the time the study was conducted, only two therapies had been approved for the treatment of AA, including one that was approved just 2 months prior to initiation of participant surveys [14, 27, 31, 32]. Based on the findings of the present study, future research should aim to address the needs identified by patients with AA.

This study had some limitations. There was reduced generalizability of study experiences as approximately one-half of all participants had lived with AA for extended periods of time, and the study only consisted of English-speaking patients in the USA. There was also limited generalizability to other measures of the psychosocial burden of AA. There was a loss of responses for AAPPO-related questions; however, this is a common limitation of using qualitative research to generate quantitative findings. Finally, this study’s sample size allowed only for inferential findings from the descriptive analyses of quantitative tools. However, the use of a mixed-methods approach enabled comparisons across quantitative and qualitative analyses, thereby strengthening any conclusions that were generated by either method in isolation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the relationship between HRQoL and initial hair regrowth can be influenced by disease and personal characteristics and the desire for amount or duration of regrowth. Specifically, the core themes identified in this study provide evidence that some patients with AA may become highly adapted to their disease and suggest that for patients with AA to consider changes to the AAPPO, high levels of hair regrowth over a sustained period of time would be required. Future research is needed to confirm these outcomes in instruments that measure similar concepts. Understanding these factors could help inform clinical practice and research.

Data Availability

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

References

Islam N, Leung PS, Huntley AC, et al. The autoimmune basis of alopecia areata: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(2):81–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.014.

Benigno M, Anastassopoulos KP, Mostaghimi A, et al. A large cross-sectional survey study of the prevalence of alopecia areata in the United States. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:259–66. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S245649.

Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(4):806-12.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035.

Abedini R, Hallaji Z, Lajevardi V, et al. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(2):91–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.07.001.

Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, et al. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S62-s68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007.

Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397–403. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S53985.

Lauron S, Plasse C, Vaysset M, et al. Prevalence and odds of depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms in children and adults with alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(3):281-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.6085.

Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, et al. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: a US survey. Int J Trichol. 2017;9(4):160–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijt.ijt_53_17.

Mostaghimi A, Napatalung L, Sikirica V, et al. Patient perspectives of the social, emotional and functional impact of alopecia areata: a systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):867–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00512-0.

Gandhi K, Shy ME, Ray M, et al. The association of alopecia areata-related emotional symptoms with work productivity and daily activity among patients with alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(1):285–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00864-1.

Mostaghimi A, Soliman AM, Li C, et al. Immune-mediated and psychiatric comorbidities among patients newly diagnosed with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(9):945-52. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.2404.

Vañó-Galván S, Blume-Peytavi U, Farrant P, et al. Physician- and patient-reported severity and quality of life impact of alopecia areata: results from a real-world survey in five European countries. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(12):3121–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01057-0

Han JJ, Li SJ, Joyce CJ, et al. Association of resilience and perceived stress in patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(1):151–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.879.

King B, Zhang X, Harcha WG, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b–3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1518–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00222-2.

Pfizer Inc. FDA approves Pfizer’s LITFULO™ (ritlecitinib) for adults and adolescents with severe alopecia areata. 2023. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/fda-approves-pfizers-litfulotm-ritlecitinib-adults-and. Accessed 29 Oct 2024.

Wyrwich KW, Winnette R, Bender R, et al. Validation of the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) questionnaire in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(1):149–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00648-z.

Sinclair R, Mesinkovska N, Mitra D, et al. Patient-reported hair loss and its impacts as measured by the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes instrument in patients treated with ritlecitinib: the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-024-00899-4.

Winnette R, Banerjee A, Sikirica V, et al. Characterizing the relationships between patient-reported outcomes and clinician assessments of alopecia areata in a phase 2a randomized trial of ritlecitinib and brepocitinib. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17909.

Sébille V, Lix LM, Ayilara OF, et al. Critical examination of current response shift methods and proposal for advancing new methods. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(12):3325–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02755-4.

Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: The Assessment, Analysis and Reporting of Patient-Reported Outcomes. New York: Wiley; 2013.

Beeken RJ, Eiser C, Dalley C. Health-related quality of life in haematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors: a qualitative study on the role of psychosocial variables and response shifts. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(2):153–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9737-y.

Washington G. Towards creation of a curl pattern recognition system. In: 2018 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision, and Pattern Recognition; 18–23 June 2018, Salt Lake City. Las Vegas: CSREA Press, ISBN (1-60132-485-5).

Gelhorn HL, Cutts K, Edson-Heredia E, et al. The relationship between patient-reported severity of hair loss and health-related quality of life and treatment patterns among patients with alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(4):989–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00702-4.

Juárez-Rendón KJ, Rivera Sánchez G, Reyes-López M, et al. Alopecia areata. Current situation and perspectives. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(6):e404-11. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2017.eng.e404.

Drake L, Li SJ, Reyes-Hadsall S, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with alopecia areata: a survey study in the USA. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9(5):342–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530356.

Hordinsky M, Hebert AA, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adolescents with alopecia areata: results from the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15378.

King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1687–99. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110343.

Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow-up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):438–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.008.

Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142.

Anderson P, Piercy J, Austin J, et al. Alopecia areata treatment patterns and satisfaction: results of a real-world cross-sectional survey in Europe. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01280-3.

Eli Lilly and Company. Highlights of prescribing information. OLUMIANT (baricitinib) tablets, for oral use. 2022. https://pi.lilly.com/us/olumiant-uspi.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2022.

Pfizer, Inc. Litfulo (ritlecitinib). Prescribing information. 2023. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=19638. Accessed March 2024.

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted at Harvard University, Putnam Associates, and Pfizer Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial support, provided by Carolyn Maskin, PhD, of Nucleus Global, was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Funding

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer also funded the journal’s publication fees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ernest Law conceived and designed the study. Adam Gibson, Georges Dwyer, and Yemi Oluboyede participated in acquisition of the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Adam Gibson, Georges Dwyer, and Yemi Oluboyede performed statistical and qualitative analysis of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Arash Mostaghimi declares receiving personal fees from Hims & Hers Health, AbbVie, SUN Pharma, Pfizer, Digital Diagnostics, Lilly, Equillium, ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Acom Healthcare, Olaplex, and Legacy Healthcare. Adam Gibson, Georges Dwyer, and Yemi Oluboyede are employees of Putnam Associates, an independent life sciences consultancy, who were employed by Pfizer to undertake this study. Iyar Mazar and Ernest Law are employees of Pfizer Inc and may own stock and/or options. Kristina Gorbatenko-Roth declares receiving research and/or consulting fees from Pfizer, National Alopecia Areata Foundation, and Procter & Gamble.

Ethical Approval

Participants provided written inform consent prior to entering the study. The study protocol and all participant-facing documentation, including the interview discussion guide, were reviewed by an independent, USA-based ethics review board (Advarra, Inc., Columbia, MD, USA), which deemed the study to be exempt from institutional review board oversight. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor, and followed generally accepted research practices described in British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association guidelines, UK Data Protection Act 2018, General Data Protection Regulation, and relevant legislations pertaining to data privacy for US participants.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: The results of this study were previously presented at Maui Derm Hawaii 2024 dermatology meeting, 22–26 January 2024, Wailea, Maui, as a poster presentation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mostaghimi, A., Gibson, A., Dwyer, G. et al. Exploring Factors That Influence the Measurement of Patient-Reported Impacts of Alopecia Areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 15, 1391–1403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-025-01400-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-025-01400-7