Key summary points

To provide evidence on effectiveness on education and training formats for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA).

AbstractSection FindingsSixty studies were included, showcasing highly heterogeneous education and training formats offered to under- and postgraduate learners of CGA performance.

AbstractSection MessageTo accelerate and optimize the implementation of CGA in clinical practice, further studies are required using more homogeneous methods, larger samples size and adequate endpoints.

Abstract

Purpose

To gather and summarize evidence on educational and training formats for medical doctors in performing Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in under- and postgraduate medical education.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using the databases Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane and Embase to identify educational intervention studies and cohort studies related to CGA education and training for medical professionals. Additional references were incorporated through reference tracking. Studies included were then grouped according to competence level addressed during CGA trainings to create a current competence-based framework on educational tools to teach CGA to medical students and doctors.

Results

Sixty eligible studies were identified, with 42 addressing the full implementation of CGA and 18 focusing on specific CGA domains. High variability in duration, intervention design and evaluation methods was consistently observed across the included studies.

Conclusion

The findings underscore the need for further coordinated research in CGA education and training to consolidate evidence and pave the way to more innovative, high-quality healthcare systems capable of addressing the complexities of an aging society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process designed to evaluate the medical, psychologic, and functional capabilities of older adults. The primary objective of CGA is to enable the development of a coordinated and integrated treatment plan, along with long-term follow-up across various care settings [1]. CGA is the technological cornerstone of geriatric medicine, grounded in a specialised interdisciplinary team approach, including medical doctors (MDs), nurses, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, dieticians, pharmacists, psychologists, to name some of the professions involved [2]. To standardize this complex assessment process, validated tools e.g. mobility assessments, nutritional and psychologic evaluation etc., have been developed and incorporated into a standardized assessment tool battery [3]. Based on CGA, several tools have been developed in the last decades, ranging from multidomain but basic screening qualitative tools to highly validated, scaled instruments enabling inter-professional co-management, clinical decision-making and integrated care [4]. CGA constitutes the very core of geriatric competence and its structured use and purpose are object of two most recent national guidelines [5, 6].

In clinical settings, medical doctors develop care plans for the management of older people and lead interprofessional teamwork, while enabling, in a flat-hierarchical, genuine interdisciplinary co-management, the exchange needed to carry out a tailored diagnostic and therapeutic care plan. Geriatricians are also responsible for communicating with patients, their families and caregivers, diagnosis and therapeutic options to offer an individualized plan in shared decision-making [7]. Needless to say, such a multifaceted set of tasks demands a broad portfolio of competencies necessary for inter-professional collaborative practice (ICP) [8].

Consequently, MDs should be equipped not only with the clinical skills required to perform CGA but also with the communication and management capabilities essential for this role. The development of such professional capabilities [9] necessitates the integration of geriatric training throughout both undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. While training recommendations, including learning objectives and entrustable professional activities (EPAs), are available for medical students and residents in geriatric medicine [10, 11], there remains a lack of clarity regarding the most effective training formats to achieve the proposed learning goals at various levels of competency and professionalism in performing CGA within an ICP setting. This gap in knowledge contributes to significant variability in the timing and structure of CGA training across medical curricula worldwide, and therefore of CGA adoption and implementation on the large needed scale.

To close this knowledge gap, the present review was designed to comprehensively address scientific evidence on CGA training formats and scenarios offered to under- and postgraduate learners of CGA performance.

Methods

Given the anticipated volume of literature on this broad topic, the authors elected to conduct a scoping review to comprehensively map the existing research.

As part of this, a comprehensive literature review was performed focusing on educational intervention studies and cohort studies related to the training of CGA for medical professionals, published between January 2000 and April 2024. Articles in English were searched across several databases, including Medline (via PubMed), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), Cochrane Libraries (via Ovid), and Embase (via Ovid). Our search strategy incorporated keywords and controlled vocabulary terms, such as the MeSH headings “professional education” OR “education and training” AND “comprehensive geriatric assessment” OR “geriatric assessment” (see search protocol as supplementary information). Where necessary, controlled vocabulary terms were adapted to fit the specific database options by utilizing relevant synonyms. In addition, a search for grey literature was performed using Google Scholar. Further studies were identified through reference tracking of the included articles. Two researchers independently conducted the title/abstract screening followed by a full-text review. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted to reach a consensus.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) randomized controlled trials, cohort studies or quasi-experimental educational intervention studies; 2) focused on undergraduate or postgraduate medical professionals, including medical students, interns, residents, geriatric fellows or other physicians; and 3) involved education and/or training in CGA as the intervention. The primary outcome of interest was the effectiveness of the educational interventions, as measured by improvements in knowledge, attitudes, clinical skills/performances, competencies, and/or patient-related outcomes. Studies that assessed outcomes through both trainee self-assessment and/or evaluations by educational providers were included.

Data charting was performed by one author and checked by a second author. The extracted data was presented in tabular form using MS Office Word software.

In a next step, authors grouped the training formats used in the publications included into different competence levels to facilitate a comprehensive overview and support choices for readers during preparing their educational interventions. To do so, authors made use of the concept of competence development, also known as the “conscious competence model” [9]. This model provides a framework for understanding the learning process in medical education. It comprises of four stages: The beginning of a learning cycle is characterized by “unconscious incompetence”. At this stage, learners are unaware of their knowledge and/or skills gaps. They are not aware of the competence gaps, which limit learners’ intrinsic motivation to learn. As learners become more aware of their deficiencies, they realize their need for support and further education. This stage is called “conscious incompetence”. At the stage of “conscious competence”, knowledge and skills, however, start to focus on application of these in practice. This implies that competences are present, not yet fully automated and applicable in an entrusted way. In the final phase of this model (“unconscious competence”), learners can perform tasks effortlessly without need to consciously think about them. Authors grouped training formats around this model, not taking in consideration assessments described in the publications to align CGA training opportunities along a learning journey of different levels of competences.

Results

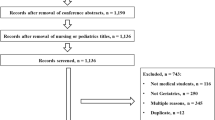

The search strategy identified a total of 1,122 studies. After removing duplicates (n = 85) and excluding studies based on title/abstract (n = 838) and full-text screening (n = 139), 60 studies were included. These consist of 42 investigations on the full CGA, holistically including the different assessment domains [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] and 18 studies on specific CGA domains, in which only certain, predominantly functional and/or cognitive capabilities of older adults were evaluated [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71].

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [72], as shown below in Fig. 1, illustrates the screening process.

Of the 42 studies on the full CGA, 26 focused on training of medical students at various levels of their undergraduate training [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], 13 of residents and interns [12, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], 1 on both groups [51], and 2 on continuous professional development programs [52, 53]. For training on specific CGA components, 15 studies were identified for undergraduate programs [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] and 3 for resident training [69,70,71]. Details of these educational studies, including those covering the full CGA and those focused on specific components, can be found in Tables 1 and 2 in the supplementary material.

In total, 6,449 students, ranging from first-year to fifth-year trainees, were included. However, three studies on undergraduate students [36, 59, 67] did not report participant numbers. The number of residents included in CGA training studies was significantly lower, totaling 1,276, with two studies failing to specify the number of participants [45, 53]. The duration of training interventions varied considerably across the included studies, comprising different time formats. Courses and/or programs incorporating geriatric content ranged in general from brief sessions of approximately 30 min [64] to comprehensive programs lasting up to four years [17]. The reported length of training formats can be categorized more specifically as follows: minutes (approx. 30 min) [64], hours (range: 1–64 h) [15, 16, 18, 25, 42,43,44, 54, 55, 57, 59, 62, 71], days (range: 0.5–3 days) [13, 29, 32, 39,40,41, 52], weeks (range: 1–10 weeks) [14, 19,20,21,22,23, 26, 34, 35, 37, 58, 66], months (range: 1–12 months) [30, 46, 48,49,50,51, 70] and years (range: 1–4 years) [17, 45, 60]. In this context, it is worth mentioning that a great number of training programs last 4 to 4.5 weeks [20, 21, 35, 66] or equivalent 1 month [30, 46, 49,50,51] and are mostly conducted as (part of) a clerkship/rotation. However, not all studies provided precise information regarding the total time required for the training. In particular, the presence of studies from different countries and continents (Europe n = 5, North and South America n = 51, Australia n = 2, Asia n = 1, Transnational n = 1) underlines the importance of the topic across geographic borders, with North America being by far the frontrunner in terms of published included studies (n = 49). In this context, however, country-specific factors must also be taken into account, whereby divergent (medical) education systems can make it difficult to align the underlying focus based on the studies included (status quo of teaching geriatrics, geriatric priorities).

There were no differences in the training formats between studies that addressed the full CGA and those that focused on individual CGA components. None of the studies provided detailed learning objectives for CGA performance. Instead, they mainly outlined the competence level expected after training. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to summarize a robust evidence-base for educational formats for different level of competences during training to be used efficiently. What may be seen from the training formats tested and enclosed into this review is a consistently high competence level addressed within most of the studies. However, the assessment tools chosen to prove efficiency of didactic formats tested in the studies did not address the competence level during training [73]. In other words, assessments evaluated knowledge gain only while addressing higher performance levels during the training sessions.

It is also interesting to see, that none of the studies included explicitly targeted team working capacities and/or collaborative practice skills as mandatory for the intrinsic mission of performing CGA and explained earlier in this paper [8]. At least this has not been outlined explicitly in the description of the different programs, nor has it been tested through the assessment instruments included in the studies. Given the nature of CGA performance in an inter- or multi-professional team together with other care providers, these findings are interesting.

Grouping results around the conscious competence model published by Keeley and colleges [9] authors could showcase, that multistep educational approaches seem to align with the aims and goals for training of CGA in a most appropriate way. Figure 2 aims at outlining this observation. During the “novice period in medical education” it seems important to create awareness for the topic of evidence-based care of older patients with complex care needs. Lectures [16, 59, 70], e-learning offers [31, 64, 68], case based teaching [31, 39, 42, 57, 59, 68, 70] and problem based learning [18, 19] seem to efficiently address leaners’ needs in this period of medical education. To translate this basic knowledge and skills into practice standardized training opportunities such as clinical skills training [18], rotations [22, 26, 39, 43, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 58], boot camps [55] and team-based learning experiences [59] have been described in literature. To support unconscious competence during daily clinical practice and performance of teamwork based on CGA, however, rotations in homecare settings [38, 61], rotations, residencies and clerkships in clinical settings with geriatric focus [22, 30, 35, 39, 40, 43, 44, 46, 50, 51, 58, 66, 70, 71, 74] seem necessary. There seems to be evidence out there, that mentoring programs, vertically integrated curricula and mandatory residencies and clerkships in geriatric environments have a strong and sustainable educational impact on the competence or working with CGA in clinical practice [17, 33, 60, 63, 66].

Illustrates a learning path inspired by a competence-development framework by Keeley and colleges [9] to master skills of performing CGA

The figure above shows the current evidence on didactic approaches tested in CGA training and outlined in the studies included in this review.

Discussion

Authors have recently published the current evidence on inter-professional education for disciplines other than MDs involved in conducting CGA [2]. In contrast, the present publication specifically focuses on the education and training of MDs in performing CGA, aiming to support academic geriatricians actively involved in education and training of MDs in this specialized field. The review assessed various training formats for students and residents at different competence levels, aiming to raise awareness of all MDs and students for the use of CGA in clinical practice. Beyond this scope, authors also tried to create an evidence base on efficacy of training formats for CGA at advanced levels of trainings for those doctors, who need to be able to perform, interpret, and discuss CGA effectively.

This scoping review could demonstrate that there are different training opportunities described for different competence levels of trainees. Formats mainly used during undergraduate medical trainings across Europe, such as lectures [16, 59, 70], e-learning offers [31, 64, 68], case-based teaching [31, 39, 42, 57, 59, 68, 70] and problem-based learnings [18, 19] are supporting awareness building and knowledge retention. Reflecting this evidence, however, towards the curriculum in geriatric medicine recommended by the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) [10], this approach will most likely not be able to prepare our medical students efficiently for the competence levels to understand and reflect results from CGA as recommended by geriatric experts. This is an important finding, as aging populations are observed in low- to middle and high-income countries globally. CGA is a key quality element in the person-centered care model for older people and every profession, especially MDs, should be capable of interpreting CGA results, discussing them with colleges and designing a corporate care plan based on patients’ goals and capacities [1].

Beyond professional standards and ethics, effective patient-physician relationship, inter-professional teamwork, role redefinition, and communication are crucial for integrated management and organization in CGA. While CGA is often used as a mechanistic scoring instrument in many healthcare systems, its role as a key aspect of geriatric medicine extends beyond mere scaling of functions. CGA should be viewed as central to inter-professional collaboration and person-centered care, regardless of the care setting. Understanding how best to equip current and future MDs with the necessary core competencies is essential, although targeted educational approaches to CGA remain challenging. Education and trainings need to bridge the gap between standardized assessments on the one hand and individualized and rather flexible methods, also including goal-oriented care planning on the other hand.

In this context, the importance of competency-based education has been thoroughly discussed in the literature. In a recently published model [75], the interplay of three layers that build a framework for competence conceptualization was discussed. Medical competence ideally consists of knowledge and skills that are required independent from professions; knowledge, skills and attitudes that are acquired within health care practices and, finally, competences that are integrated into an individual’s personality, which cannot be standardized and contribute to a dynamic and diverse health care workforce. In addition, competency-based education allows priority setting in health care and offers a mechanism to incorporate contextual health needs with health workforce development.

Our recent work already demonstrated the effects of advanced inter-professional training methods for professions involved in CGA and not being MDs, to maximize the impact of CGA in clinical practice [2]. However, beyond inter-professional training offers, geriatricians should consider their role in shaping future generations of MDs. The most important finding of our work in the context of medical education is the effectiveness of vertically integrated training programs for CGA, utilizing diverse didactic tools (see Fig. 2) [63]. Mentoring programs, rotations, and clerkships with geriatric focus appear to enhance training outcomes [17, 22,23,24, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 38, 39, 43, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 58, 60, 66, 76]. Virtual teaching and (online) learning management systems pose an essential factor in this regard, as technology-based teaching and learning environments foster education and democratize knowledge in a flexible manner [77].

In a bibliometric review [77], six thematic clusters were identified that highlight important aspects to gain a holistic picture of sustainable virtual teaching modalities: In detail, clusters relate to (1) the prevalent function of technological tools to create virtual teaching experiences, (2) the significance of qualified educators, (3) the necessity of frameworks and governance structures that guide virtual teaching possibilities, (4) a careful consideration of students’ and learners’ experiences and perspectives, (5) the importance of basic technological and digital infrastructure for successful virtual teaching, and finally (6) a needs-oriented integration and adaptation of curricula. There is no doubt that higher education is facing the issue of successfully teaching complex skills to students. Against the previously discussed background, a well-balanced interaction of theory, interventions and technological support promote the achievement of complex thinking and skills, even in particular educational situations and contexts [78], as is often required when addressing specific clinical needs of older adults in different settings.

CGA has been shown to improve outcomes for older adults in both hospital and community settings [79], as it encompasses health and social care needs and promotes multidisciplinary collaboration of various health care professions. A recent paper highlights the need for new care models to integrate CGA for the majority of older patients in non-geriatric hospital units. It also suggests that incorporating geriatric learning objectives into undergraduate training and developing practice guidelines for geriatric syndromes could improve care quality for older patients [80]. Our work may serve as a starting point for connecting geriatricians and interested readers, and for designing research environments to address existing questions.

Despite the extensive number of participants, the studies included in our review has several major limitations. Although a variety of didactic approaches were tested across different competence stages, many training formats were supported by only one or two studies. Another significant limitation is the quality of the included studies. With reference to study and evaluation design, there are mentionable differences in the approach restraining objectivity and comparability of the studies. While a large proportion of studies were only conducted as “uncontrolled” single-arm [12,13,14,15, 17,18,19, 21, 22, 27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54,55,56, 59, 60, 62, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] or observational research [36, 63], others were carried out as multi-arm studies and/ or used one or more control groups [16, 20, 23,24,25,26, 28, 37,38,39, 42, 44, 47, 50, 53, 57, 58, 61] (e.g., to compare with traditional teaching or using different didactic methods and/or tools) to create better opportunities for comparison. Quality deficiencies are also evident in the evaluation format, as on the one hand a pre-post assessment cannot be found uniformly among all included studies, in some cases the assessment is explicitly carried out merely post-intervention [13, 24, 33, 37, 41, 61, 62, 65, 66, 71], which refers to missing baseline and thus comparing data. On the other hand, there is a high risk of subjective or biased data based on a partially included self-evaluation. In addition to the above mentioned facts, many studies exhibited a mismatch between educational goals and assessment methods [73]. Notably, several studies on residency and internship training, which are primarily workplace-based, focused on lower levels of competence, such as assessing knowledge [40, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 70, 71] or self-rated confidence in performing CGA [39, 42, 43, 69, 70]. In contrast, undergraduate training studies typically measured knowledge, attitudes, skills [15, 16, 18, 20,21,22, 25,26,27,28, 30, 32,33,34,35,36, 54,55,56, 59, 61, 63, 64, 66], or professional competence [14, 23, 31], regardless of the students’ year of training. A clear alignment between training formats, participant training levels, and assessment methods was often lacking, posing a significant barrier to interpreting the results. Given the methodologically weak evidence, there is a substantial need for further research in this field.

Based on these insights, authors strongly recommend continued research in the area of geriatric education and training, leveraging the robust networks of geriatricians within Europe and internationally. One potential avenue for progress is through collaboration within the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) and the European Union of Medical Specialists– Geriatric Medicine Section (UEMS-GMS), which recently secured a European grant under the COST program, PROGRAMMING CA21122 (https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA21122/). This initiative aims to build networks among stakeholders in older care and geriatrics across Europe and foster implementation of needs-oriented education and training in geriatric medicine.

References

Rubenstein LZ, Siu AL, Wieland D (1989) Comprehensive geriatric assessment: toward understanding its efficacy. Aging (Milano) 1(2):87–98

Lindner-Rabl S, Singler K, Polidori MC, Herzog C, Antoniadou E, Seinost G et al (2023) Effectiveness of multi-professional educational interventions to train Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA): a Systematic Review. Int J Integr Care 23(3):9

Wieland D, Ferrucci L (2008) Multidimensional geriatric assessment: back to the future. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63(3):272–274

Kudelka J, Ollenschläger M, Dodel R, Eskofier BM, Hobert MA, Jahn K et al (2024) Which Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) instruments are currently used in Germany: a survey. BMC Geriatr 24(1):347

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geriatrie (DGG) e.V. S3-Leitlinie "Umfassendes Geriatrisches Assessment (Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment CGA) bei hospitalisierten Patientinnen und Patienten". Langversion 1.1. AWMF-Registernummer: 084–003.; 2024

Pilotto A, Aprile PL, Veronese N, Lacorte E, Morganti W, Custodero C et al (2024) The Italian guideline on comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for the older persons: a collaborative work of 25 Italian Scientific Societies and the National Institute of Health. Aging Clin Exp Res 36(1):121

Chadborn NH, Goodman C, Zubair M, Sousa L, Gladman JRF, Dening T et al (2019) Role of comprehensive geriatric assessment in healthcare of older people in UK care homes: realist review. BMJ Open 9(4):e026921

Roller-Wirnsberger R, Lindner S, Liew A, O’Caoimh R, Koula ML, Moody D et al (2020) European Collaborative and Interprofessional Capability Framework for Prevention and Management of Frailty-a consensus process supported by the Joint Action for Frailty Prevention (ADVANTAGE) and the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS). Aging Clin Exp Res 32(4):561–570

Keeley C (2021) Conscious competence model and medicine. Foot Ankle Surg Tech Rep Cases 1:100053

Masud T, Blundell A, Gordon AL, Mulpeter K, Roller R, Singler K et al (2014) European undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine developed using an international modified Delphi technique. Age Ageing 43(5):695–702

Roller-Wirnsberger R, Masud T, Vassallo M, Zöbl M, Reiter R, Van Den Noortgate N et al (2019) European postgraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine developed using an international modified Delphi technique. Age Ageing 48(2):291–299

Thillainadesan J, Naganathan V, Hilmer SN, Kerdic R, Aitken SJ (2023) Microlearning for surgical residents enhances perioperative comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc 71(12):E30–E33

Goldlist K, Beltran CP, Rhodes-Kropf J, Sullivan AM, Schwartz AW (2022) Out of the classroom, into the home: medical and dental students’ lessons learned from a Geriatrics home visit. J Am Geriatr Soc 70(9):2659–2665

Ng ZL, Mat Din H, Zakaria NF, Inche Mat LN, Wan Zukiman WZH, Md Shah A et al (2021) Implementation of a healthcare of elderly course with multi-professional teachers for undergraduate medical students in a public university in Malaysia-a quasi-experimental pre and post study. Front Public Health 9:743804

Lucchetti ALG, Duarte BSVF, de Assis TV, Laurindo BO, Lucchetti G (2019) Is it possible to teach Geriatric Medicine in a stimulating way? Measuring the effect of active learning activities in Brazilian medical students. Australas J Ageing 38(2):e58–e66

Lucchetti ALG, Ezequiel ODS, Oliveira IN, Moreira-Almeida A, Lucchetti G (2018) Using traditional or flipped classrooms to teach “Geriatrics and Gerontology”? Investigating the impact of active learning on medical students’ competences. Med Teach 40(12):1248–1256

Mendoza De La Garza M, Tieu C, Schroeder D, Lowe K, Tung E (2018) Evaluation of the Impact of a senior mentor program on medical students’ geriatric knowledge and attitudes toward older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 39(3):316–325

Goeldlin AO, Siegenthaler A, Moser A, Stoeckli YD, Stuck AE, Schoenenberger AW (2014) Effects of geriatric clinical skills training on the attitudes of medical students. BMC Med Educ 14:233

Mappilakkandy RK, Krauze S, Khan I (2014) 96 teaching comprehensive geriatric assessment to medical students via modified problem based learning–a pilot project in northampton general hospital. Age Ageing 43(suppl_1):i26

van de Pol MH, Lagro J, Fluit LR, Lagro-Janssen TL, Olde Rikkert MG (2014) Teaching geriatrics using an innovative, individual-centered educational game: students and educators win. A proof-of-concept study. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(10):1943–1949

Tam KL, Chandran K, Yu S, Nair S, Visvanathan R (2014) Geriatric medicine course to senior undergraduate medical students improves attitude and self-perceived competency scores. Australas J Ageing 33(4):E6-11

Atkinson HH, Lambros A, Davis BR, Lawlor JS, Lovato J, Sink KM et al (2013) Teaching medical student geriatrics competencies in 1 week: an efficient model to teach and document selected competencies using clinical and community resources. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(7):1182–1187

Igenbergs E, Deutsch T, Frese T, Sandholzer H (2013) Geriatric assessment in undergraduate geriatric education: a structured interpretation guide improves the quantity and accuracy of the results: a cohort comparison. BMC Med Educ 13:116

Strano-Paul L (2011) Effective teaching methods for geriatric competencies. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 32(4):342–349

Sutin D, Rolita L, Yeboah N, Taffel L, Zabar S (2011) A novel longitudinal geriatric medical student experience: using teaching objective structured clinical examinations. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(9):1739–1744

Diachun L, Van Bussel L, Hansen KT, Charise A, Rieder MJ (2010) “But I see old people everywhere”: dispelling the myth that eldercare is learned in nongeriatric clerkships. Acad Med 85(7):1221–1228

Zwahlen D, Herman CJ, Smithpeter MV, Mines J, Kalishman S (2010) Medical students’ longitudinal and cross-sectional attitudes toward and knowledge of geriatrics at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(10):2049–2050

Denton GD, Rodriguez R, Hemmer PA, Harder J, Short P, Hanson JL (2009) A prospective controlled trial of the influence of a geriatrics home visit program on medical student knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards care of the elderly. J Gen Intern Med 24(5):599–605

Fisher AL, O’Keefe EA, Hanlon JT, Studenski SA, Hennon JG, Resnick NM (2009) A brief, intensive, clinically focused geriatrics course during the third year of medical school. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(3):524–529

Oates DJ, Norton LE, Russell ML, Chao SH, Hardt EJ, Brett B et al (2009) Multisite geriatrics clerkship for fourth-year medical students: a successful model for teaching the Association of American Medical Colleges’ core competencies. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(10):1917–1924

Goldman LN, Wiecha J, Hoffman M, Levine SA (2008) Teaching geriatric assessment: use of a hybrid method in a family medicine clerkship. Fam Med 40(10):721–725

Sanchez-Reilly SE, Wittenberg-Lyles EM, Villagran MM (2007) Using a pilot curriculum in geriatric palliative care to improve communication skills among medical students. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 24(2):131–136

Bates T, Cohan M, Bragg DS, Bedinghaus J (2006) The medical college of Wisconsin senior mentor program: experience of a lifetime. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 27(2):93–103

Roscoe LA, Schonwetter RS, Wallach PM (2005) Advancing geriatrics education: evaluation of a new curricular initiative. Teach Learn Med 17(4):355–362

Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA (2005) Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(11):2007–2011

Newell DA, Raji M, Lieberman S, Beach RE (2004) Integrating geriatric content into a medical school curriculum: description of a successful model. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 25(2):15–32

Duque G, Gold S, Bergman H (2003) Early clinical exposure to geriatric medicine in second-year medical school students–the McGill experience. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(4):544–548

Flaherty JH, Fabacher DA, Miller R, Fox A, Boal J (2002) The determinants of attitudinal change among medical students participating in home care training: a multi-center study. Acad Med 77(4):336–343

Chao SH, Kwok JY, Ubani BN, Rogers REP, Stark RL (2022) Teaching medicine interns minimum geriatrics competencies within a “4 + 2” schedule. J Am Geriatr Soc 70(1):251–258

Brown MM, Halpert K, Dale M, Helton M, Warshaw G (2020) Advanced geriatrics evaluation skills. Fam Med 52(3):206–208

Ford CR, Loyd C, Rothrock AG, Johnson TM, Allman RM, Brown CJ (2019) Development and evolution of a two-day intensive resident experience in geriatric medicine. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 42(1):24–37

Phillips SC, Hawley CE, Triantafylidis LK, Schwartz AW (2019) Geriatrics 5Ms for primary care workshop. MedEdPORTAL 15:10814

Chang C, Callahan EH, Hung WW, Thomas DC, Leipzig RM, DeCherrie LV (2015) A model for integrating the assessment and management of geriatric syndromes into internal medicine continuity practice: 5-year report. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 38(3):271–282

Hogan TM, Hansoti B, Chan SB (2014) Assessing knowledge base on geriatric competencies for emergency medicine residents. West J Emerg Med 15(4):409–413

Saffel-Shrier S, Gunning K, Van Hala S, Farrell T, Lehmann W, Egger M et al (2012) Residency redesign to accommodate trends in geriatrics: an RC-FM variance to establish a patient-centered medical home in an assisted living facility. Fam Med 44(2):128–131

Ahmed NN, Farnie M, Dyer CB (2011) The effect of geriatric and palliative medicine education on the knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(1):143–147

McLeod TG, McNaughton DA, Hanson GJ, Cha SS (2009) Educational effectiveness of a personal digital assistant-based geriatric assessment tool. Med Teach 31(5):409–414

Baum EE, Nelson KM (2007) The effect of a 12-month longitudinal long-term care rotation on knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents about geriatrics. J Am Med Dir Assoc 8(2):105–109

Maurer MS, Costley AW, Miller PA, McCabe S, Dubin S, Cheng H et al (2006) The Columbia Cooperative Aging Program: an interdisciplinary and interdepartmental approach to geriatric education for medical interns [corrected] [published erratum appears in J AM GERIATR SOC 2006 Sep; 54(9):1479]. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(3):520–526

Steinweg KK, Cummings DM, Kelly SK (2001) Are some subjects better taught in block rotation? A geriatric experience. Fam Med 33(10):756–761

McCrystle SW, Murray LM, Pinheiro SO (2010) Designing a learner-centered geriatrics curriculum for multilevel medical learners. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(1):142–151

Eckstrom E, Desai SS, Hunter AJ, Allen E, Tanner CE, Lucas LM et al (2008) Aiming to improve care of older adults: an innovative faculty development workshop. J Gen Intern Med 23(7):1053–1056

Vass M, Avlund K, Lauridsen J, Hendriksen C (2005) Feasible model for prevention of functional decline in older people: municipality-randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4):563–568

Hagiwara Y, Pagan-Ferrer J, Sanchez-Reilly S (2018) Impact of an early-exposure geriatrics curriculum in an accelerated baccalaureate-MD program. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 41(4):508–513

Omlor RL, Watkins FS, Lawlor JS, Lovato JF, Fino NF, Atkinson HH (2016) Intern Boot Camp: feasibility and impact of a 1-hour session to ensure graduating medical student competency in falls risk assessment. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 38(3):346–353

Demons JL, Chenna S, Callahan KE, Davis BL, Kearsley L, Sink KM et al (2014) Utilizing a meals on wheels program to teach falls risk assessment to medical students. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 35(4):409–420

Rughwani N, Gliatto P, Karani R (2014) Long case or case vignettes: a comparison of two instructional methods in inpatient geriatrics for medical students. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 36(2):161–184

St Onge J, Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, McLeod H, Marr S (2013) Impact of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on the care of older acute medical patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Med Educ 13:168

Ouchida K, LoFaso VM, Capello CF, Ramsaroop S, Reid MC (2009) Fast forward rounds: an effective method for teaching medical students to transition patients safely across care settings. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(5):910–917

Duke P, Cohen D, Novack D (2009) Using a geriatric mentoring narrative program to improve medical student attitudes towards the elderly. Educ Gerontol 35(10):857–866

Tung EE, Thomas MR (2008) Use of a geriatric home visit experience to teach medical students the functional status assessment. J Gen Intern Med 24(2):244–246

Adelman RD, Capello CF, LoFaso V, Greene MG, Konopasek L, Marzuk PM (2007) Introduction to the older patient: a “first exposure” to geriatrics for medical students. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(9):1445–1450

Supiano MA, Fitzgerald JT, Hall KE, Halter JB (2007) A vertically integrated geriatric curriculum improves medical student knowledge and clinical skills. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(10):1650–1655

Ruiz JG, Smith M, Rodriguez O, Van Zuilen MH, Mintzer MJ (2007) An interactive E-learning tutorial for medical students on how to conduct the performance-oriented mobility assessment. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 28(1):51–60

Williams BC, Hall KE, Supiano MA, Fitzgerald JT, Halter JB (2006) Development of a standardized patient instructor to teach functional assessment and communication skills to medical students and house officers. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(9):1447–1452

Powers CS, Savidge MA, Allen RM, Cooper-Witt CM (2002) Implementing a mandatory geriatrics clerkship. J Am Geriatr Soc 50(2):369–373

Penn MA, Smucker W, Logue E (2001) Functional and attitudinal outcomes of teaching functional assessment to medical students. Educ Gerontol 27(5):361–372

Swagerty D Jr, Studenski S, Laird R, Rigler S (2000) A case-oriented web-based curriculum in geriatrics for third-year medical students. J Am Geriatr Soc 48(11):1507–1512

Moriarty JP, Wu BJ, Blake E, Ramsey CM, Kumar C, Huot S et al (2018) Assessing resident attitudes and confidence after integrating geriatric education into a primary care resident clinic. Am J Med 131(6):709–713

Caton C, Wiley MK, Zhao Y, Moran WP, Zapka J (2011) Improving internal medicine residents’ falls assessment and evaluation: an interdisciplinary, multistrategy program. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(10):1941–1946

Robbins MR (2002) Training family medicine residents for assessment and advocacy of older adults. J Am Osteopath Assoc 102(11):632–636

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Biggs J (1996) Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ 32(3):347–364

Diachun LL, Klages KB, Hansen KT, Blake K, Gordon J (2012) The comprehensive geriatric assessment guide: an exploratory analysis of a medical trainee performance evaluation tool. Acad Med 87(12):1679–1684

ten Cate O, Khursigara-Slattery N, Cruess RL, Hamstra SJ, Steinert Y, Sternszus R (2024) Medical competence as a multilayered construct. Med Educ 58(1):93–104

Steele C, Cayea D, Berk J, Riddell R, Kumra T, McGuire M et al (2019) Novel first-year curriculum in high-value care. Clin Teach 16(5):513–518

Makda F (2024) Digital education: Mapping the landscape of virtual teaching in higher education – a bibliometric review. Educ Inform Technol

Xu H, Deng T, Xu X, Gu X (2024) The effectiveness of educational interventions on thinking and operational skills in complex learning—a meta-analysis. Think Skills Creativ 53:101574

Veronese N, Custodero C, Demurtas J, Smith L, Barbagallo M, Maggi S et al (2022) Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older people: an umbrella review of health outcomes. Age Ageing 51:5

Stuck AE, Masud T (2022) Health care for older adults in Europe: how has it evolved and what are the challenges? Age Ageing 51(12):1–7

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roller-Wirnsberger, R., Herzog, C., Lindner-Rabl, S. et al. Teaching Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in medical education: a scoping review. Eur Geriatr Med 16, 425–433 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-025-01157-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-025-01157-4