Abstract

Background

The 1994 genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda resulted in the tragic loss of over one million lives and severely damaged social fabric of the country. The long-term effects of this massacre are most apparent in the persistent psychosocial challenges affecting multiple generations. In response, Prison Fellowship Rwanda introduced the Action-Based Reconciliation Model (ABRM), which has shown a noticeable impact on reconciliation and psychosocial healing. However, this model has not been extensively investigated. Thus, this study explored the prominence of ABRM in fostering psychosocial recovery and practical reconciliation in Rwanda.

Methods

This research employed qualitative research design to explore the impact of ABRM on psychosocial healing and reconciliation among genocide survivors and perpetrators living in reconciliation villages and neighbouring communities. Data collection involved 12 focus group discussions, with six groups from reconciliation villages and six from surrounding communities. Discussions were structured to capture experiences, perceptions and interactions of participants. All discussions were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analyses.

Results

Genocide survivors reported experiencing depression, hopelessness, resentment, and trauma before moving to reconciliation villages, while the families of perpetrators dealt with fear, shame, guilt, and self-stigma. Both groups indicated that living in reconciliation villages fostered a sense of re-humanization. This shared journey toward healing involved forgiveness and repentance, leading to practical reconciliation, trust, and improved social cohesion. The environment within the villages facilitated collaboration, the restoration of friendships, and positive coexistence. However, communities outside the reconciliation villages reported ongoing wounds among survivors and former prisoners, which impeded social cohesion and trust, particularly in comparison to those within reconciliation villages.

Conclusion

While ABRM has noticeably facilitated reconciliation and psychosocial healing, obstacles remain extant such as reluctance of ex-prisoners to openly share their experiences, and persistent psychological distresses linked to limited livelihood resources. Policymakers should continue to support these initiatives and promote international collaboration with organizations and peace-building agencies to exchange knowledge and resources, ensuring the successful implementation of reconciliation actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The transition from the 20 th to the twenty-first century has been marked by extreme social injustices, armed conflicts, and genocides that have left long-lasting impacts [1]. Notable examples include the Holocaust (1933–1945), the Armenian genocide (1915), the Cambodian genocide (1975–1979), the genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda (1994), and the Yugoslav crisis and genocide (1995) [2,3,4]. These traumatic events, characterized by violence, killings, and destruction, have caused enduring psychological, social, and economic damages not only for survivors, victims, and perpetrators [5, 6] but also for their descendants across generations [7, 8]. For instance, the Armenian genocide, despite occurring over a century ago, continues to affect future generations [9]. Similarly, the genocide against the Tutsis has left profound intergenerational legacies for families of both survivors and perpetrators [10,11,12].

Globally, post-genocide and conflict societies face a critical need for psychosocial restoration, reconciliation, and social cohesion to heal trauma and rebuild harmonious communities [13,14,15]. In Rwanda, the genocide against the Tutsis created numerous challenges, including Dislocated social fabric, mental health crises, and widespread poverty that sometimes transmit through generations [16, 17]. However, government-led initiatives and partnerships with organizations have played a essential role in mitigating these harmful impacts [18, 19]. A significant challenge in such societies is rebuilding relationships between groups previously involved in conflict. Effective reconciliation requires rebuilding trust, reducing prejudice, and fostering positive interactions between offenders, survivors, and victims as well as their descendants and families [20, 21].

Unity and social cohesion leading to reconciliation, recognized as the cornerstone of peace-building, is one of the most challenging steps in the aftermath of mass atrocities. It seeks to address massive violations of human rights, ethnic cleansing, apartheid, occupation, war crimes, and other forms of systemic discrimination [22]. Scholars and practitioners widely agree that reconciliation is an ongoing process rather than a static outcome, aiming to develop relationships between individuals, groups, and societies [21, 23]. In this context, reconciliation requires psychological transformations within groups and considers the collective memory of past events [24, 25]. Research in social psychology emphasizes the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural changes necessary for reconciliation, guided by frameworks such as Allport’s Contact Hypothesis, which highlights the value of cooperative intergroup efforts toward shared goals [26, 27]. Examples from post-conflict settings, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, illustrate the importance of meaningful intergroup contact in fostering reconciliation and social cohesion. Initiatives like interethnic youth projects and cooperative problem-solving workshops have successfully reduced intergroup biases and promoted coexistence [28, 29]. These findings underscore the necessity of creating opportunities for intergroup contact, education, and collaboration to rebuild trust and foster forgiveness.

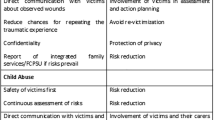

Drawing on the principles of reconciliation, the Rwandan government and its partners have made notable efforts to implement policies and interventions aimed at addressing the aftermath of the genocide. However, Rwandan communities—where survivors live alongside perpetrators or their descendants—continue to struggle with significant challenges comprising ongoing collective and transgenerational trauma, mutual mistrust, and stigma. Due to these challenges, various scholars and the government continue encouraging to enhance unity and social cohesion, and eradicate genocide ideology [16, 30, 31]. One of promising initiatives to counter genocide ideologies is the creation of “Reconciliation Villages,” which utilize the transformative power of joint occupations. In these villages, survivors and perpetrators collaborate to build homes, co-developing income-generating initiatives, and sharing lives [12]. These villages represent a distinctive action-based reconciliation model (ABRM), initiated by Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR), designed to facilitate collective efforts toward reconciliation [32, 33]. The ABRM consists of several key components, including (a) community dialogues on unity and reconciliation, (b) trained reconciliation counselors and facilitators, (c) shelter provision for target groups, (d) collaboration between survivors and perpetrators, (e) labor exchange programs for survivors’ daily needs, (f) progressive dialogue and forgiveness, (g) fostering mutual trust and understanding, (h) practical reconciliation efforts, (i) improved mental health and social cohesion, and (j) a replicable framework for post-conflict societies (Table 1).

Reconciliation villages provide shared living spaces for genocide survivors, former perpetrators, and vulnerable community members, integrating joint livelihood activities, dialogue sessions, and spiritual programs. These prominent efforts contribute to rebuilding trust, promoting forgiveness, and enhancing psychological well-being while fostering coexistence and reducing intergroup bias. The ABRM involves several practices and activities [34, 35]. The reconciliation village model aligns with Freeman’s proposed strategies for enhancing intergroup contact, including cooperative farming, community-based empowerment, and participation in national identity programs like “Ndi Umunyarwanda” (“I am Rwandan”) [36,37,38].

Although the ABRM has been recognized as an innovative and grassroots solution in post-conflict settings, the effect of reconciliation villages on psychosocial well-being and livelihoods has not been thoroughly explored. This study seeks to address this gap by investigating the influence of reconciliation villages on psychological well-being, practical reconciliation, and community livelihoods. The specific objectives are to: (a) explore the impact of the ABRM on the psychological well-being of residents from eight reconciliation villages; (b) investigate the successes of the model in reducing intergroup bias, fostering trust, promoting coexistence, forgiveness and reconciliation; and (c) understand the opportunities and challenges experienced by residents of these villages. The findings from this research are intended to offer critical insights to guide policymakers and stakeholders in supporting ongoing efforts to promote psychosocial healing, practical reconciliation, and social cohesion in post-genocide context.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Study design, settings and population

This study used qualitative methods to gain a deep understanding of the experiences of participants hailing from diverse social backgrounds, including released genocide prisoners, genocide survivors, new returnees, and local leaders from the Eastern Province (the largest province in Rwanda) and Northern Province. The research took place in eight reconciliation villages strategically located across different districts: Rweru in Bugesera District (Eastern Province), Kamonyi in Musanze District (Northern Province), Kageyo in Kayonza District (Eastern Province), and Mwili and Nyawera in Ngoma District (Eastern Province). These villages were established between 2003 and 2012 as part of comprehensive post-genocide recovery initiatives, aimed at fostering healing and rebuilding community ties. Currently, they support approximately 830 direct beneficiaries (Table 2). This study also recruited participants from the surrounding communities of these reconciliation villages.

For participants recruited from the reconciliation villages, the following inclusion criteria applied: (a) participants must be residents of one of the eight reconciliation villages affiliated with the PFR; (b) both genocide survivors and perpetrators residing in the villages were eligible to participate; (c) participants must be aged 25 years and over; (d) participants must be willing to provide informed consent to take part in the study; (e) participants should be open to sharing their experiences related to the research topics; and (f) participants must have lived in the reconciliation village for at least six months to ensure they have experienced the impact of the ABRM. Exclusion criteria included: (a) individuals under 25 years of age; (b) individuals who were unable to provide informed consent; (c) individuals who had lived in the village for less than six months; (d) individuals unable to communicate verbally due to any disability; (e) individuals who did not actively engage in the reconciliation processes, such as joint activities or dialogue sessions; and (f) individuals who were not residents of the reconciliation villages, even if they had benefited from the model. For participants from surrounding communities the reconciliation villages, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (a) participants must be aged 25 years and older; (b) genocide survivors and perpetrators were eligible; (c) participants must come from communities outside the reconciliation villages but within the broader study region; (d) participants must be willing to provide informed consent; (e) participants must be willing to share their experiences related to genocide. Exclusion criteria for this group included: (a) persons not residing in the communities under study; (b) individuals who could not provide informed consent; (c) individuals who were unable to communicate verbally; and (d) persons who had not lived in the community for at least six months.

2.2 Sampling procedure and sample size

Non-probability sampling methods were employed to investigate how a select group of individuals residing in a shared village articulate their viewpoints concerning the post-genocide reconciliation process in Rwanda. The primary focus groups in this study included the genocide perpetrators, and genocide survivors from reconciliation villages and those from their surrounding communities. To gather participants for the qualitative segment of the research, consecutive sampling was utilized. The sample size for this phase was determined through the utilization of data saturation, the point at which further data collection no longer yields novel insights or themes.

2.3 Data collection

The qualitative data aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants’ lived experiences concerning the study's central themes and related questions. To achieve this, five reconciliation villages with the largest populations were selected: Rweru, Kamonyi, Kageyo, Mwili, and Nyawera. One focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted in each village, with each group consisting of 10 participants drawn from diverse social backgrounds: 4 genocide survivors, 4 perpetrators, and 2 other community members residing in the same village. In total, five FGDs were conducted, all of which were digitally recorded. Additionally, five FGDs were carried out in surrounding communities of the reconciliation villages, maintaining the same social categories (4 genocide survivors, 4 perpetrators, and 2 community members). The discussions were facilitated by two researchers and supported by two research assistants who took notes and managed the recordings. These FGDs were held in comfortable, familiar settings such as schools, churches, and participants'homes within the communities. This approach created a conducive environment for the exploration of key topics raised by the participants, enabling a more profound and nuanced understanding of their experiences.

A convenience sampling technique was used to select participants, with the saturation method applied to ensure comprehensive coverage of the themes during the FGDs. Separate interview guides were developed for participants from the reconciliation villages and those from surrounding communities. Participants from the reconciliation villages were asked to describe their experiences before and after living in the villages, their perceptions of the relationship between genocide perpetrators and survivors, factors hindering or enabling reconciliation, and the role of the village in fostering reconciliation. They were also asked about their socio-economic experiences and how living in the same village contributed to sharing the truth related to genocide crimes. For the newly released prisoners, the interviews focused on their experiences before and during victim-offender reconciliation dialogues, their motivations to participate, challenges faced, and whether their expectations were met. They were also asked about the contribution of the reconciliation dialogues to truth-telling, interpersonal healing, and sustainable peace, as well as recommendations for the reintegration of ex-prisoners. Further, participants from surrounding communities the reconciliation villages discussed their perceptions of ex-prisoners before and after release, the effects of the genocide, the relationship between survivors and perpetrators in their communities, and factors enabling or hindering reconciliation. Along with proposing suggestions for successful reconciliation and reintegration, participants were also asked about the attitudes of the community, local authorities, and ex-offenders toward them. The duration of the interviews ranged from 55 to 1 h and 51 min. At the end of the interview, participants requested us to share with them a summary report of the findings from this research.

2.4 Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymized during the process to eliminate any identifying information. After transcription process, the data were translated from the native language of participants (Kinyarwanda) into English by two skilled researchers who are fluent in both languages and well-acquainted with the context of the involved community members. The transcripts were analyzed through thematic analysis. This method followed a series of key steps to systematically organize, condense, refine, and analyze the data. Three researchers (EB, FB and JK) read each transcript thoroughly, with a sample reviewed by a second researcher to ensure that anonymity, transcription accuracy, and contextual integrity were maintained. Two members of the research team (EB and FB) carried out the initial analysis, generating early codes and identifying potential themes by gathering all relevant data for each proposed theme. Further, two researchers (DG, and JK) examined and resolved any discrepancies in the proposed themes, thereby enhancing the rigor and minimizing potential bias in the analysis process. Subsequent meetings with the entire research team facilitated reaching a consensus on the themes, which were then named and defined. In the final interpretive phase, illustrative quotations were used to support each theme, showcasing the insights derived from the analysis. The data analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti version 5.2.

2.5 Ethics

This study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration report. The research was granted ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rwanda, College of Medicine and Health Sciences (IRB/CMHS), under reference number (No.: 224/CMHS IRB/2020). Stringent measures were in place to uphold confidentiality and privacy between the researchers and participants. Before participating in the study, all participants received a comprehensive explanation of the research procedures and methods. So, all participants provided signed informed consent forms. Their involvement in the study was entirely voluntary, and participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any point without providing any reason. To ensure the utmost protection of participants, data collection was anonymously conducted. Participants authorized the publication of the results from this research.

3 Results

The results section presents findings from our study on genocide survivors and perpetrators in reconciliation villages and their surrounding communities. Key distinct themes were generated from the participates shared experiences: (i) Impact of intergroup contact and collective activities on mutual relationships and economic empowerment; (ii) Role of reconciliation villages in enhancing psychosocial well-being through intergroup engagement; (iii) fostering reconciliation through trust-building and truth-telling in intergroup interactions; (iv) Psychosocial dynamics and roles of structured reconciliation processes; and (v) barriers to practical reconciliation among genocide survivors and perpetrators.

3.1 Impact of intergroup contact and collective activities on mutual relationships and economic empowerment

Based on the qualitative research conducted among genocide survivors and perpetrators living in reconciliation villages compared to those residing outside these villages, several key findings emerged regarding the impact of socio-economic initiatives on reconciliation. Respondents noted that bringing survivors and perpetrators together in the same cooperative groups—where they share tasks such as cultivating land, supporting each other during both positive events (such as wedding) and difficult times (like burials)—significantly fosters reconciliation. This collaborative environment not only promotes positive social relationships but also supports overall development for all involved. In addition, participants in reconciliation villages have actively engaged in community-driven initiatives to meet their socio-economic needs. An illustrative example of this is the cooperative efforts and resource management within these communities, which enhance collective wellbeing. The following account highlights how these cooperatives address basic needs, plan for future projects, and emphasize democratic decision-making processes within the village.

“We have a cooperative named ABUNZUBUMWE, we started by raising chicken but we sold it due to the illness, another thing we have a hall that we rent on 60,000 frw per month, we also have 100 plastic chairs and we rent it on 100 frw/one, so these are items that support us to cover some basic needs’ hope that after the COVID-19 we will initiate new projects as we plan to have general meeting soon in two weeks. Decisions on what to do are taken equally here in this village,” a genocide survivor from reconciliation village stated.

In contrast, participants from surrounding communities expressed a lack of trust among neighbours and limited collaboration, primarily due to unresolved mutual distrust. This mistrust has hindered their ability to work together effectively, leaving their livelihoods in a precarious state. A genocide survivor from a community outside the reconciliation villages shared:

“Perpetrators killed our family members and some of them have not fully acknowledged their role in the genocide crimes. They need to tell us the truth so that we can trust them, and this can improve unity and social cohesion process.”

In exploring the lived experiences of individuals residing in reconciliation villages, many participants shared stories of profound personal transformation and community rebuilding. These narratives often emphasized the importance of collective efforts and the supportive environment fostered within these villages. The following quote from a participant poignantly captures this experience, illustrating not only the process of reintegration after imprisonment but also the role of communal initiatives in promoting socio-economic development and reconciliation among former adversaries. One of former genocide prisoners said:

“I was released from correctional facility in 2010, and found that the reconciliation village was built and my family was living there because they gave them a house to live in. I continued to live well with my family members and genocide survivors. We have been working together on various projects to help us grow and get socio-economic development. Together with the genocide survivors, I joined a cooperative named"Twuzuzanye".

3.2 Role of reconciliation villages in enhancing psychosocial health through intergroup engagement

In evaluating the psychological and emotional effects of living in reconciliation villages, participants noted significant improvements in their mental health and overall well-being. Their perspectives illustrate how the reconciliation village environment has facilitated healing and renewed hope for those who had previously suffered from severe depression and suicidal thoughts. Most genocide survivors reported feeling depressed and hopeless before moving to the villages, while perpetrators described experiencing fear, shame about their crimes, and stigma from the community. These reflections emphasize the transformative influence of the reconciliation village on their mental health and sense of purpose. As one genocide survivor testified:

“The hope for future was restored in my life, since I started living in reconciliation village. I am no longer feeling depressed or stigmatized because of my diseases. I would say that living in reconciliation village was a God’s purpose of protecting me from my suicidal ideation due to severe depression”.

In examining the profound effects of reconciliation villages, one poignant testimonial encapsulates the transformation experienced by individuals who have spent years in these communities. This personal account highlights the deep psychological and emotional relieve that can occur as a result of living in an environment focused on reconciliation and forgiveness. The participant's reflections offer a compelling illustration of how reconciliation villages contribute to overcoming past traumas and fostering a sense of peace and well-being. However, most of participants from surrounding communities reported still suffer from emotional distresses from their painful past, and this is due to not being engaged in a joint constructive and guided dialogue on healing and reconciliation.

“Now 17 years living in reconciliation village, my heart doesn’t beat like it used to do before. The fear I had is gone, I have the peace of mind after having reconciled with people I betrayed. I can now sleep well,” said by a former prisoner. The genocide perpetrator from the community surrounding reconciliation village said, “We were released from the correctional facility and we now live with the genocide survivors in the same community. But we did not attend the sessions like those from reconciliation villages. So, without a structured environment to support us, we always feel painful and have share….”

The process of reconciliation is deeply intertwined with the ability to openly address past grievances and seek forgiveness. Participants, both genocide survivors and ex-prisoner of genocide, often spoke about how dialogue and the act of apology play crucial roles in fostering reconciliation. The following statement illustrates the core belief that reconciliation is achievable when individuals have the chance to discuss their past actions and seek forgiveness, and when survivors find it within themselves to forgive those who have wronged them. A former prisoner of genocide voiced:

“Reconciliation is possible when people get opportunities to talk about the crimes they have committed and apologize; genocide survivors are able to forgive the offenders.”

Participants shared powerful testimonies about the transformative, life-altering impact of receiving support and care related to residing in reconciliation villages. They conveyed deep gratitude and acknowledged the crucial, life-saving role of the reconciliation village where they live. The fact that they live together in these areas has helped them feel restored from their painful past. A genocide survivor remarked:

“If I didn't come to live here, I would be dead.”

Participants observed varying degrees of change among released genocide prisoners, highlighting a contrast between those who showed no behavioral transformation and those who demonstrated genuine repentance and personal growth. One genocide survivor noted the emotional difficulty of interacting with former perpetrators but also expressed a sense of relief when greeted by the genocide survivors who had changed. The survivor acknowledged ongoing challenges related to depression and fear but expressed gratitude for their survival and hope for continued peace, emphasizing the complex emotional landscape shaped by the reconciliation process. A genocide survivor expressed:

“There are some of genocide prisoners who were released and are living in our communities but their behaviours and attitudes do not indicate significant changes after their sentence. Sometimes, we observe they are afraid of us, as we fear them. Nevertheless, among other released former genocide inmates, you can realize that they repented and changed, and when you greet them, even if it is difficult, you feel relieved. Due to depression, we sometimes feel unable to greet the genocide perpetrators. Thanks to God because we are still alive and we hope that no one will cut us again like what happened to us in the genocide.”

Participants reflected on their personal transformations and fears related to their past actions. Genocide offenders recounted feelings of profound self-devaluation and self-loathing due to their crimes. They also expressed initial fears of retaliation from victims upon their release, although these fears ultimately proved unfounded. This testimony highlights the intense emotional struggles encountered and the surprising realities of reintegration into society, illustrating the complexity of overcoming past wrongs and adapting to a new life. An ex-prisoner articulated:

“I was incarcerated for 11 years and I felt devalued and I considered myself as an animal because the heaviness of the atrocities I committed. I used to think about the people around me; I thought that upon my release, the victims would revenge against me, but it was not the case”.

The study participants highlighted the significant changes in their interactions and perceptions of former threats since moving to the reconciliation village. They also described their initial fear and avoidance to meet genocide perpetrators, which was fuelled by past trauma and the emotional effects of their experiences. They reported their avoidance of public commemorations and dialogues about the genocide due to triggers of their trauma. However, since relocating to the reconciliation village, they have experienced a restoration of their trust and social relationships with former genocide inmates, now coexisting harmoniously and offering mutual support, reflecting the profound impact of the reconciliation process on their daily lives. One of genocide survivor expressed:

“When I look at how we lived with those who offended us, I notice we live healthier when compared to our life before coming to reconciliation village. When we lived outside the village, we were living with those who killed our relatives, but we were afraid of them and they were ashamed of what they did also. I was so afraid of the genocide perpetrators that I did not want to meet them or talk to them due to the genocide crime against us. I felt like I didn't want to go to church. I could not go to genocide commemoration events, even in April of each year. I didn't want to listen to commemorative dialogues about the genocide (on radio, TV or in conferences). These were triggers of my trauma. When I met a genocide perpetrator, I became afraid of him and immediately went back to avoid that he could greet me or kill me. But today in reconciliation village, we live in harmony with them. Today, if I meet a genocide perpetrator who has a machete going to his farm, I cannot be afraid of him as it was before joining to reconciliation village. They are not afraid of us either, or look as murders. Today when we meet, we talk with them and help each other.”

3.3 Fostering reconciliation through trust-building and truth-telling in intergroup interactions

In the reconciliation villages, the genocide survivors and genocide perpetrators expressed that before they came to the reconciliation villages, they suffered from psychological distresses and social problems, but reconciliation village has been for them a doctor who treated their wounds and social distresses which negatively affected their level of reconciliation. Within the framework of the ABRM, forgiveness was framed as an important result of social cohesion, interaction experiences engaging in purposeful actions and interactions, significantly contributing to healing by fostering mutual understanding and reconciliation between survivors and perpetrators. The findings revealed not only instances of both decisional and emotional forgiveness but also inner transformation. Living in the same reconciliation villages and participating actively in psychosocial healing dialogues allowed survivors to receive constructive support from perpetrators, while offering perpetrators the chance to seek healing from survivors. A genocide survivor from reconciliation village said:

“The experience of witnessing perpetrators’ sincere devotion in labour accumulated over the course of sessions paralleled the temporal transformation of forgiveness from decisional to love. The hard work of a perpetrator finally touched a survivor’s heart.”

A genocide survivor said “I have forgiven him already. I don’t have a problem with him anymore. He is always committed while working for me without any problem… What increases (in me) is a love, not forgiveness. Forgiveness has been granted. Now it is the love that increases.” In addition to that, living together has contributed towards sharing the truth related to genocide crimes (bodies of the victims, restitution, etc.) and practical reconciliation:

“I'm telling the truth that the genocide perpetrators didn't say very bad things to us. They didn't insult or hit us. We also do not insult them or harm them. Rather, we work together, especially in cooperatives or socio-economic groups; we pray together, our children study together; we fetch water together,” A genocide survivor from reconciliation village expressed.

Participants from the surrounding communities shared their perspectives on the population residing within it. Both genocide survivors and ex-prisoners from these neighbouring communities testified that they observe those from reconciliation village collaborate and support one another through various activities, including labouring, livestock farming, and cooperatives, which foster practical reconciliation and strengthen social connections. In our neighbours from reconciliation villages, everyone is aware of the identities of survivors and perpetrators, as well as the dynamics of their relationships. Although some community members questioned the collaboration, the joint labor consistently explained their efforts as “practical reconciliation,” known locally as “ubwiyunge nyabwo,” inspired by the “Igiti cy’umuvumu” translated as “sycamore tree program”. A genocide perpetrator added:

“There is a feeling of mistrust among us, because we have not yet had enough opportunities to meet those who offended us in comparison of those who live in reconciliation villages. We would also wish to do so.”

However, participants from the reconciliation villages emphasized that their collaborative efforts are driven by a deep commitment to fostering genuine reconciliation rather than financial incentives. They expressed a strong desire to rebuild a resilient community and demonstrate to the world that Rwandans are actively engaged in a meaningful process of healing and unity. The ex-prisoner from reconciliation villages expressed:

“We are not doing this for money. We are doing this because we are committed to this reconciliation in action and we wish to restore a resilient community because we wish the rest of world know that Rwandans are in the process of genuine reconciliation.”

Some of the genocide survivors from the communities surrounding the reconciliation villages said that they live in poor conditions in comparison to their colleagues who are living in the reconciliation village. They said that they want development. They consider residents of Mbyo reconciliation village as ones who have a better quality of life than they do. So, they wish to become inhabitants of the reconciliation village too. They said that in a reconciliation village, people are engaged in various joint activities such as agriculture; tailoring, and cooperatives, and these activities bring together the genocide survivors and ex-prisoners. They also take time for dialogues and solving together their social problems. In the reconciliation village, tourists give them money. As expressed by a former inmate from the surrounding community:

“The genocide perpetrators who live in Mbyo reconciliation village apologized for their genocide crimes. Genocide survivors forgave them. Both former genocide inmates and genocide survivors participated in the building of houses in which they are living together, they share life, they always meet, and they pray together, they have more in common than we do. When one of them lacks water, his neighbour gives it to him, and if he has a problem, they help him; they are generally united and have many things in common that we do not have. In our community, we do not have these experiences which means that we still have to apologise for crimes and reconstruct our community”

Participants from communities outside the reconciliation villages shared varied experiences regarding reconciliation. Many genocide perpetrators expressed a willingness to apologize for their actions but highlighted the lack of supportive spaces that would allow them to share their experiences openly. Meanwhile, survivors revealed that lingering emotional wounds hinder their ability to discuss past events with perpetrators. One perpetrator said “I want to apologize for what I did, but I don’t know how. Sometimes I think about it, but I can’t bring myself to do it. Without trust, the truth feels too heavy to share.”

3.4 Psychosocial dynamics and roles of structured reconciliation processes

The group of beneficiaries from reconciliation villages and those from the surrounding community were interviewed separately to ensure that their specific contexts and dynamics were captured effectively. During the interviews, we found diverse perspectives that showed important differences between these groups. Our results indicated that respondents from reconciliation villages, who lived in close proximity to both genocide survivors and perpetrators, often expressed a greater sense of openness and willingness to share their experiences. Participants from reconciliation villages, who lived near both survivors and perpetrators, often expressed a greater sense of openness and willingness to share their experiences. This openness could be attributed to the structured reconciliation processes within the villages, which have helped foster trust and reduce fear. The participants showed the sense of safety and openness fostered by being integrated in the reconciliation villages model where survivors and perpetrators engage in structured interactions that assist them in rebuilding trust. The genocide survivors from reconciliation village articulated:

“Living in this community, we learn to talk openly about what happened. We work together, and even though it was hard in our first days to come in this village we’ve come to understand each other. Our children play and help each other. I no longer feel afraid to share my thoughts, even when the past comes up. When our village have visitors, either survivor or perpetrator share our past experiences and testimonies of changes.”

In contrast, participants from surrounding communities showed remarkable apprehension and fear when discussing sensitive topics related to the impact of genocide. This could stem from unhealed trauma and unresolved psychosocial wounds, as these persons may not have fully undergone similar reconciliation processes or experienced the same level of structured support to address their psychosocial distresses and trauma. The participants from these communities presented the apprehension that could be due to unresolved trauma and lack of structured opportunities for supportive dialogues and healing.

“Some time, I feel reluctant, and afraid of being judged or misunderstood. You can meet a survivor and she greets me. It’s not easy to talk when you don’t know how others will react, especially when wounds from the past are still there.”

3.5 Barriers to practical reconciliation among genocide survivors and perpetrator

Among the factors hindering reconciliation, most of the respondents especially survivors from the surrounding communities, reported not burying the bodies of their loved ones as one as the most challenge to reconciliation. It was highlighted that prisoners are not willing to show where bodies of the genocide victims who were killed were thrown, this truth is quite hidden. Moreover, mental health related to these issues, low level of reconciliation; genocide ideologies observed among youth and the lack of psychological interventions to address the above-mentioned health conditions are relevant issues that hindering reconciliation process:

“Another thing is the inability to explain where people who were killed are buried; the cows were eaten by whom? All of this, delays unity and reconciliation” articulated by a genocide survivor from the surrounding communities.

Furthermore, the unsatisfactory level of genuine confession and forgiveness were mentioned by some of research participants from surrounding communities. An ex-prisoner from surrounding community said:

“Repentance and forgiveness can well happen among genocide survivors and former genocide inmates who participated in Sycamore tree program, compared to those who did not get chance to participate in the program. The majority of us did not know the truth about genocide crimes committed against our relatives, and did not organize a decent burial of their loved ones who were killed in genocide. There is a need for fostering joint healing and reconciliation dialogues also in communities outside reconciliation villages.”

The fact that parents who went through genocide atrocities are unable to communicate with their decedents or children on these issues is also a hindrance to unity and social cohesion. In some cases, misinformation shared by parents further exacerbates the suffering of children, who continue to bear the weight of the legacy of genocide. On the other hand, participants from reconciliation villages highlighted several factors that have facilitated reconciliation. They noted that acts of apology and forgiveness have fostered visits and interactions between former opponents, reducing fear among ex-prisoners and the families of genocide survivors. A small number of respondents also emphasized that revealing the truth about genocide crimes has significantly eased the reconciliation process. A genocide survivor said:

“I noticed that seeking forgiveness is the main element in reconciliation process, in addition I can highlight that the truth sharing as another key element of reconciliation because the truth accompanies even our children, by knowing the truth; they grow bearing in mind how to avoid bad things, said a mother genocide survivor who lives in reconciliation village”.

4 Discussions

The findings from this study revealed that the inhabitants of reconciliation villages have a lower level of mental disorders such as depression than the residents from the surrounding communities. These findings corroborate the prior studies that reconciliation villages are notable initiatives for promoting peace-building and have great contribution to a reduction of mental distresses such as trauma-associated identities among survivor and perpetrator gradually become less salient, while reconciliation village residents have an opportunity to rediscover each other through their present- and future-oriented socioeconomic roles and identities [39]. Consistent with studies showing higher mutual trust levels among individuals who live closely and interact frequently [40], reconciliation villages showed stronger social trust and control than residents from their neighbouring communities. This trust is bolstered by shared opportunities, including regular meetings and collaborative engagement in socio-economic activities.

The respondents expressed that reconciliation village has served as a crucial tool for strengthening their social identity and fostering a sense of national unity through togetherness. This is because after they experience psychosocial healing, they also develop social cohesion and networks that are important as a good start of reconciliation and recovery especially for the people who experienced traumatic events. These findings align with previous studies showing that social participation considerably improves mental health and reduces social exclusion [41]. The participatory gatherings that promote social transformation and collective action parallel the reconciliation villages, which unite individuals to rebuild social identity and enhance social engagement, supporting one another in addressing mental health challenges linked to past experiences.

Our findings revealed that the genocide survivors forgave the genocide perpetrators and this reconciliation increased the friendship between the two groups and helped to foster unity among them. Although forgiveness refers to a voluntary, conscious decision taken by the victim or survivor to abandon negative feelings toward another who has caused hurt and replacing those feelings with unconditional love and compassion [42]. However, our results highlighted a contrasting reality in communities surrounding the reconciliation villages, as revealed through interviews and observations conducted by the researchers who work closely with the residents of the reconciliation villages. Respondents from these areas reported lower levels of reconciliation and forgiveness, primarily due to the persistent social distance between genocide survivors and perpetrators, which has hindered the establishment of genuine unity and reconciliation. Our findings showed that genocide survivors forgave the perpetrators, and this act of reconciliation strengthened friendships between the two groups, fostering unity. Forgiveness, in this context, involves a voluntary and conscious decision by the survivor to release negative feelings toward the offender and replace them with compassion and unconditional regard [43, 44].

In accordance with the previous studies [28, 45], genocide survivors and perpetrators expressed that forgiving past wrongdoings has become their major key to reconciliation between friends, family members, spouses, neighbours and cultures. The findings showed that the genocide survivors and perpetrators from the reconciliation villages have a better self-esteem than the respondents from the surrounding communities. This is because living in the reconciliation villages—as the way of closer contacts contributes to their social identity and reduction of social chauvinism—became a great opportunity to increase their quality of life, empathy, and help each other. But in the communities the genocide perpetrators are still in need of finding an enabling environment that could help them to increase their interaction with genocide survivors. Reconciliation villages also enabled the practical reconciliation through joint socio-economic initiative among genocide perpetrators and genocide survivors. These support the previous studies whose results showed the impact of reconciliation villages on socio-economic development, reconstructing community resilience and peace-building [46].

In agreement with the previous research on the impact of forgiveness on life [46, 47], the results from this survey revealed that the process of forgiveness from both the ex-genocide inmates and the genocide survivors was a great way of living longer and way to get better life. The entire experience was very moving, to say the least. These results are supported by the previous studies on transformative capacity of communication; achievement of civil and peaceful cooperation with former enemies as co-citizens relies (in part) on this transformative capacity [48].

Our findings revealed that confessions, remorse, apology and forgiveness played a very big role. These results are supported by the previous studies [49]. It eased the process of prosecuting offenders; it removes suspicion among genocide perpetrators and genocide survivors. In addition, it relieves perpetrators who apologise. As far as testimonies are concerned, the research has found that they heal survivors. This process also contributes to heal or educate the young generation. Our results also asserted that truth telling contributed and continues to contribute much on reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda. Research findings also revealed an improved process of asking and granting forgiveness between ex-inmates, families of prisoners and survivors in the reconciliation village, compared to those from surrounding communities who are still struggling to overcome their feeling of mistrust and suspicion. The results corroborate the previous studies [49, 50] which reported a weaker community belonging related to mental health problems, though a stronger association was observed with mental health for the offenders and victims who do not get enabling environment for healing and forgiveness.

While the respondents expressed that they had vowed to act in a good faith to become community catalysts in promoting reconciliation and social cohesion in the reconciliation villages, in the surrounding communities they showed that their stigma and trauma related to genocide are still obstacles for an effective social cohesion. Interestingly, some of the genocide survivors from the communities expressed that they have unconditional forgiveness since they have already forgiven independently the genocide perpetrators. Our results are supported by the prior studies which showed that the victims can develop unconditional forgiveness for healing his wounds and become resilient [43, 51, 52]. The concept of conditional forgiveness posits that before forgiveness can be granted, the offender must take certain steps and meet specific conditions. From an unconditional forgiveness concept, the victim can forgive independently of the behaviour of the wrongdoer. The results corroborate the previous studies [53, 54].

The survey results yielded a fascinating insight into the substantial role played by both genocide survivors and perpetrators residing in reconciliation villages in facilitating the successful execution of national reconciliation programs. Furthermore, respondents highlighted that within these communities, society has borne witness to and experienced the values of tolerance, forgiveness, and social cohesion, fostering an atmosphere where community members willingly embrace harmonious coexistence. These findings align with earlier studies emphasizing the significance of community dialogues in promoting reconciliation [39]. Reconciliation villages have emerged as a unifying force, nurturing a sense of unity and shared identity among former genocide prisoners and survivors. Additionally, a significant number of respondents from the neighbouring communities expressed a strong desire to reside in the reconciliation villages. They view this as a means to progress in their reconciliation journey, recognizing it as a healing process. These findings align with prior research, underscoring that reconciliation villages form an integral component of a government-backed reconciliation and peace-building initiative [33, 35]. In these villages, select genocide perpetrators, who have received official pardons, undergo peace-building training and are provided with resources to actively participate alongside genocide survivors in constructing village infrastructure and fostering a sense of community [33, 55].

It is often believed that genocide survivors and victims cannot easily coexist or interact with their offenders; given the profound traumatic events and histories they have endured. The pain, mistrust, and emotional scars make it seemingly impossible for them to share activities or build connections [56,57,58]. However, our study presents a contrasting perspective. We found evidence that, in certain contexts, survivors, victims, and perpetrators are living together in the same villages. Remarkably, they engage in shared activities, utilize communal assets, and support one another in their daily lives. This unexpected coexistence demonstrates the potential for reconciliation and psychosocial reintegration, even after such profound suffering. The results from our studies revealed that residing in the reconciliation villages provided genocide perpetrators with a valuable opportunity to understand the importance of fostering unity and reconciliation. This was achieved through acts of repentance, confession, and seeking forgiveness from survivors—steps they had previously resisted. In contrast, some ex-inmates living in neighbouring communities reported feeling a persistent sense of shame and stigma, which discouraged them from approaching genocide survivors to seek forgiveness.

4.1 Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study possesses several key strengths that make it a valuable contribution to the field. First, it addresses a critical gap in research, as no prior studies were conducted by PFR to explore the levels of mental disorders and reconciliation, especially in the context of genocide survivors and perpetrators. This research ascertains a solid foundation for future policy and program development, underlining the necessity for ongoing support in reconciliation initiatives and international collaboration to mitigate the long-term effects of genocide. Second, the study’s robust sample, encompassing participants from both the reconciliation villages and surrounding communities, provides a rich and diverse data set. This enables a comprehensive analysis and meaningful comparison of mental health outcomes between these two distinct populations. Third, the adoption of qualitative methods allowed for an in-depth exploration of the experiences and perspectives of participants, providing important understandings that quantitative approaches may not capture. The inclusion of multiple sources of data collection strengthens the validity of the findings and ensures a holistic understanding of the lived experiences of those involved in the reconciliation process. These strengths underscore the significance of this research in advancing our understanding of post-genocide reconciliation and its impact on mental health, offering essential evidence to guide future interventions and policy-making.

This study faced several limitations. Firstly, it did not assess the impact of the ABRM on psychosocial health and its predictors, requiring further inquiry to establish causal relationships between reconciliation villages and mental health outcomes. The absence of a detailed longitudinal framework also limits the ability to track changes over time and assess the long-term sustainability of the eminence of ABRM on psychosocial health especially on practical reconciliation. Secondly, the use of a cross-sectional study design limited the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the causal relationship between increased psychosocial healing and in reconciliation villages. Thirdly, the sample size was limited, and it did not compare psychosocial outcomes between genocide survivors and perpetrators assigned to ABRM and those who were not. Besides, some ex-prisoners declined participation for personal reasons, which may have introduced response bias. Additionally, factors such as variations in individual experiences and pre-existing mental health conditions were not accounted for in detail, potentially affecting the generalizability of the results. Lastly, in measuring the contribution of ABRM to fostering reconciliation, a pre and post-test design with a randomly assigned comparison groups would have been ideal. However, due to the urgent implementation of the healing and reconciliation program, a post-test only design was employed with two groups matched on certain characteristics. While this design has limitations, such as the absence of a baseline assessment and randomization for an equivalent control group, it was the most feasible option for providing information within the context of the implemented intervention. The study selected a comparison group that closely resembled the ABRM but couldn't guarantee complete comparability between the two groups. Future research should adopt experimental or quasi-experimental designs to strengthen causal inferences regarding the effectiveness of ABRM.

5 Conclusions

Our study revealed a substantial disparity in mental health and reconciliation outcomes between participants from reconciliation villages and those in surrounding communities. Individuals in reconciliation villages presented a remarkable reduction in the psychosocial difficulties and an considerable surge of social cohesion. They also reported stronger community support, and tangible reconciliation progress in post-genocide period. This transformative shift is primarily driven by the close proximity and collaborative initiatives within the ABRM, which cultivate trust and thoroughly dismantle psychosocial and emotional barriers between survivors and perpetrators. Conversely, the genocide survivors and perpetrators residing in surrounding communities continue to grapple with persistent psychosocial challenges, including limited access to joint healing and reconciliation dialogues—critical factors that undermine trust and mutual support between released genocide inmates and survivors.

Although participants from reconciliation villages showed notable improvements, certain psychosocial challenges persist, requiring continued engagement through this model. Moreover, those affected by the genocide who reside in surrounding communities should also be integrated into ABRM practices to extend its benefits. Our findings reinforce the perspective that structured reconciliation programs, when combined with mental health support, play a crucial role in fostering lasting peace-building and social stability.

Our results suggest that the ABRM approach, as applied in reconciliation villages, could serve as an important model for communities surrounding these villages and other post-conflict societies. This approach not only facilitates healing and reconciliation but also contributes to long-term psychosocial recovery and social cohesion, making it a noticeable strategy for peace-building efforts. To ensure the sustainability of such initiatives, continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation of the model are necessary, addressing emerging challenges and incorporating community feedback.

To maintain these achievements, it is essential to establish a multidisciplinary team that includes government institutions, private organizations, and both national and international stakeholders. This collaboration would help sustain psychosocial reconstruction efforts, fostering cooperation and dialogue among diverse groups. Additionally, we recommend integrating community development approaches, which empower local populations to take an active role in healing processes, thereby ensuring a sustainable and grassroots-driven recovery. Future research should incorporate longitudinal studies to examine the long-term effects of reconciliation programs on mental health and social cohesion. Further, studies should explore gender-specific experiences, as reconciliation and trauma responses may differ across various demographic groups, allowing for more targeted and effective interventions. Such research would offer critical insights into the sustainability and efficacy of these initiatives, further refining strategies for post-genocide recovery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Haller T. The role of the United Nations in the prevention of genocide. Assumption University; 2020. https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/honorstheses/78.

Haperen M, Have W, Kiernan B, Mennecke M, Üngör U, Zwaan T (2012) The holocaust and other genocides. In: NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Amsterdam University Press, 2012; p. 176.

Münyas B. Genocide in the minds of Cambodian youth: transmitting (hi) stories of genocide to second and third generation in Cambodian. J Genocide Res. 2008;10(3):413–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520802305768.

Shelton D. Encyclopedia of genocide and crimes against humanity. The University of Winnipeg; 2004.

Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Psychiatric genocide: Nazi attempts to eradicate schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp097.

Gangadharan L, Islam A, Ouch C, Wang LC. The long-term effects of genocide on antisocial preferences. World Dev. 2022;160: 106068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106068.

Berckmoes LH, Eichelsheim V, Rutayisire T, Richters A, Hola B. How legacies of genocide are transmitted in the family environment: a qualitative study of two generations in Rwanda. Societies. 2017;7(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7030024.

Bar-On D. Transgenerational aftereffects of the holocaust in Israel: three generations. In: Sicher E, ed. Breaking crystal: writing and memory after Auschwitz. Efraim Sicher.Urbana (Ill.). University of Illinois Press; 2010; pp. 91–118.

Kizilhan JI, Noll-Hussong M, Wenzel T. Transgenerational transmission of trauma across three generations of alevi kurds. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010081.

Roth M, Neuner F, Elbert T. Transgenerational consequences of PTSD: risk factors for the mental health of children whose mothers have been exposed to the Rwandan genocide. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2014;8(12):1–12.

Rudahindwa S, Mutesa L, Rutembesa E, et al. Transgenerational effects of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda: a post-traumatic stress disorder symptom domain analysis. AAS Open Res. 2020;1:10. https://doi.org/10.12688/aasopenres.12848.2.

Biracyaza E, Habimana S. Contribution of community-based sociotherapy interventions for the psychological well-being of Rwandan youths born to genocide perpetrators and survivors: analysis of the stories telling of a sociotherapy approach. BMC Psychol. 2020;9:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00471-9.

Staub E. Building a Peaceful Society: origins, prevention, and reconciliation after genocide and other group violence. Am Psychol. 2013;68(7):576–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032045.

Nadler A, Malloy T, Fisher J. The social psychology of intergroup reconciliation: from violent conflict to peaceful co-existence. First edit. Oxford University Press, USA; 2008.

Nadler A, Shnabel N. Intergroup reconciliation: instrumental and socio-emotional processes and the needs-based model. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2015;26(1):93–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2015.1106712.

Gishoma D, Brackelaire JL, Munyandamutsa N, Mujawayezu J, Mohand AA, Kayiteshonga Y. Remembering and re-experiencing trauma during genocide commemorations: the effect of supportive-expressive group therapy in a selected district hospital in Rwanda. Rwanda J Ser F Med Health Sci. 2015;2(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/rj.v2i2.8F.

King E. Memory controversies in post-genocide rwanda: implications for peacebuilding. Genocide Stud Prev. 2010;5(3):293–309. https://doi.org/10.1353/gsp.2010.0013.

National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC). Assessing the Reintegration of Ex-Genocide Prisoners in Rwanda: Success and Challenges.; 2010. https://www.nurc.gov.rw/fileadmin/Documents/Others/NURC__Social_reintegration_of_ex-prisoners_reintegration.pdf.

Clark P. The Gacaca courts, post-genocide justice and reconciliation in Rwanda: justice without lawyers. Cambridge University Press; Illustrated edition (Sept. 9 2010); 2010.

Schiller R. Reconciliation in Aceh: addressing the social effects of prolonged armed conflict. Asian J Soc Sci. 2011;39(4):489–507.

Bloomfield D, Barnes T, Huyse L. Reconciliation after violent conflict: a handbook. In: Bloomfield D, Barnes T, Huyse L, editors. Handbook series. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/law-mpeipro/e3045.013.3045.

Rouhana N. Key issues in reconciliation: challenging traditional assumptions on conflict resolution and power dynamics. Intergroup conflicts and their resolution. In: A social psychological perspective. Psychology Press; 20011.

Fischer M. Transitional justice and reconciliation: theory and practice. In: Austin B, Fischer M, Giessmann H, eds. Advancing conflict transformation: the bergh of handbook. Second. Opladen/Framington Hills: Barbara Budrich Publishers; 2011; pp. 406–430.

Van AJ, Bostyn D, De KJ, Dardenne B, Hansenne M. Intergroup reconciliation between flemings and walloons: the predictive value of cognitive style, authoritarian ideology, and intergroup emotions. Psychol Belg. 2017;57(3):132–55. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.333.

Dovidio J, Vergert T, Stewart T, et al. Perspective and prejudice: antecedents and mediating mechanisms. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(12):537–1549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271177.

Barlow FK, Hornsey MJ, Thai M, Sengupta NK, Sibley CG. The wallpaper effect: the contact hypothesis fails for minority group members who live in areas with a high proportion of majority group members. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12): e82228. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082228.

McKeown S, Dixon J. The, “contact hypothesis”: critical reflections and future directions. Soc Personal Psychol. 2017;1(1): e12295. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12295.

Freeman C. The psychosocial need for intergroup contact: practical suggestions reconciliation initiatives in Bosnia and Herzegovina and beyond. Interv Int J Ment Heal Psychosoc Work Couns Areas Armed Confl. 2012;11(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/WTF.0b013e3283518de1.

Licata L, Klein O, Saade W, Azzi AE, Branscombe NR. Perceived out-group (Dis)continuity and attribution of responsibility for the Lebanese Civil War mediate effects of national and religious subgroup identification on intergroup attitudes. Gr Process Intergr Relat. 2012;15(2):179–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430211414445.

Jansen S, White R, Hogwood J, et al. The “treatment gap” in global mental health reconsidered: Sociotherapy for collective trauma in Rwanda. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:1–6. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.28706.

Straus S. Studying perpetrators: a reflection. J Perpetrator Res. 2017;1(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.21039/jpr.v1i1.52.

Masahiro M. Action-based psychosocial reconciliation approach: Canadian Counselling Psychological Contribution to Interpersonal Reconciliation in Post-Genocide Rwanda. 2019.

Minami M. Ubwiyunge Mubikorwa (reconciliation in action): development and field piloting of action-based psychosocial reconciliation approach in post-Gacaca Rwanda. Intervention. 2020;18(2):129–38. https://doi.org/10.4103/INTV.INTV_5_20.

Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR). Prison Fellowship Rwanda Profile.; 2019. https://pfrwanda.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PFR-ANNUAL-REPORT-2019-FINAL.pdf.

Mafeza F. Restoring relationship between former genocide perpetrators and survivors of genocide against Tutsi in Rwanda through reconciliation villages. Int J Dev Sustain. 2013;2(2):787–98.

Paradis R. The intersectional experience of Ndi Umunyarwanda: an interdisciplinary analysis of identity & removing Ubwoko in Rwanda. Undergrad J Glob Citizsh. 2020;3(2). https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc/vol3/iss2/3

Sentama E. National reconciliation in Rwanda: experiences and lessons learnt. Middle East Dir. 2022;05:22.

NURC. National unity and reconciliation commission: unity and reconciliation process in Rwanda.; 2016. https://truthcommissions.humanities.mcmaster.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/UNITY-AND-RECONCILIATION-PROCESS-IN-RWANDA.pdf.

Lordos A, Ioannou M, Rutembesa E, Christoforou S, Anastasiou E, Björgvinsson T. Societal healing in Rwanda: toward a multisystemic framework for mental health, social cohesion, and sustainable livelihoods among survivors and perpetrators of the genocide against the tutsi. Health Hum Rights. 2021;23(1):105–18.

Khaile FT, Roman NV, October KR, Staden M, Balogun TV. Perceptions of trust in the context of social cohesion in selected rural communities of South Africa. Soc Sci. 2022;11:359. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080359.

Baxter L, Burton A, Fancourt D. Community and cultural engagement for people with lived experience of mental health conditions: what are the barriers and enablers? BMC Psychol. 2022;10(71). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00775-y.

Mullen L, Bistany B, Kim J, et al. Facilitation of forgiveness: impact on health and well-being. Holist Nurs Pr. 2022;37(1):15–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000559.

Robles JMJ, Kim JC. On forgiveness and reconciliation in post-conflict societies: a philosophical perspective. Bauru. 2016;4(2):223–36. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203740323-11.

Toussaint L, Owen A, Cheadle A. Forgive to live: forgiveness, health, and longevity. J Behav Med. 2012;35(4):375–86. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM21.3.1.

Campbell A. Forgiveness and reconciliation as an organizational leadership competency within transitional justice instruments. Int J Servant-leadersh. 2017;11(1):139–86. https://doi.org/10.33972/ijsl.92.

Brewer MB, Gaertner SL. Toward reduction of prejudice: intergroup contact and social categorization. In: Brown R, Gaertner SL, editors. Blackwell handbook of social psychology: intergroup processes. New York: Wiley; 2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470693421.ch22.

Shnabel N, Nadler A, Ullrich J, Dovidio JF, Carmi D. Promoting reconciliation through the satisfaction of the emotional needs of victimized and perpetrating group members: the needs-based model of reconciliation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720933661.

Pukallus S. The transformative capacity of communication: integrative communicative acts across the communicative spectrum of civil society. In: Pukallus S, editor. Communication in peacebuilding. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86190-2_5.

Michalski C, Diemert L, Helliwell J, Goel V, Rosella L. Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages. SSM Popul Health. 2020;12(12): 100676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100676.

Palis H, Marchand K, Oviedo-Joekes E. The relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated mental health among Canadians with mental or substance use disorders. J Ment Health. 2018;29(2):168–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1437602.

Prieto-Ursúa M, Jódar R, Gismero E, Carrasco MJ, Martínez MP, Cagigal V. Conditional or unconditional forgiveness? An instrument to measure the conditionality of forgiveness. Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Spain; 2016. https://repositorio.comillas.edu/rest/bitstreams/176062/retrieve.

Toussaint LL, Shields GS, Slavich GM. Forgiveness, stress, and health: a 5-week dynamic parallel process study. Physiol Behav. 2017;176(1):100–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9796-6.Forgiveness.

Prieto-Ursúa M, Jódar R, Gismero-Gonzalez E, Carrasco MJ, Martínez MP, Cagigal V. Conditional or unconditional forgiveness? An instrument to measure the conditionality of forgiveness. Int J Psychol Relig. 2018;28(3):206–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2018.1485829.

Brookes DR. Forgiveness as conditional: a reply to Kleinig. Int J Appl Philos. 2021;35(1):117–25. https://doi.org/10.5840/ijap2021129157.

Traverso A, Broderick M. Forgiveness is something that can be seen from behind’. Visualizing a conversation with a perpetrator and a survivor of the 1994 Rwandan genocide in a reconciliation village. Continuum (NY). 2020;34(2):299–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1737439.

Staub E. The challenging road to reconciliation in rwanda: societal processes, interventions and their evaluation. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2014;2(1):505–17. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v2i1.294.

Brudholm T, Rosoux V. The unforgiving: reflections on the resistance to forgiveness after atrocity. Theor Post-Conflict Reconcil Agon Restit Repair. 2013;2008:115–30. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203144473.

Lewis J. Impossible reconciliation? The representation of traumatic memories in La meilleure façon de s’aimer (2012) by Akli Tadjer. Contemp Fr Civiliz. 2022;47(3):339–56.

Acknowledgements

All authors appreciate the partners of PFR particularly the districts leaders of Musanze, Ngoma, Kayonza, and Bugesera, where the reconciliation villages are located, for their collaboration and partnership. Our appreciation also extends to partners of PFR specifically Norwegian Church Aid (NCA), Prison Fellowship International, and Association des Amis de la Fraternité Internationale de Prison, for their support in the construction of the reconciliation villages in the post-genocide. Our gratitude goes to the participants who accepted to participate.

Funding

The study did not receive external financial support; instead, PFR staff provided financial support for data collection and securing ethical approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FB, EB, and JK contributed to data acquisition. FB and EB conceived and drafted the manuscript, made substantial contributions to data analysis, and interpretation of the results. DG and CK reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the design of the study. FB, and EB revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. DG played a supervisory role and provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study obtained an ethical approval from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences of the University of Rwanda (No. 224/CMHS IRB/2020). Before data collection, all participants furnished both verbal and written informed consent. Confidentiality and voluntariness were rigorously upheld throughout the entire research process. This study adhered to the guidelines and standards of the Helsinki Declaration reports.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bigabo, F., Biracyaza, E., Kanazayire, C. et al. Reconciliation villages in post-genocide Rwanda, beyond rhetoric to practical reconciliation and psychosocial reintegration. Discov Soc Sci Health 5, 60 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-025-00201-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-025-00201-9