Abstract

We retrospectively reviewed charts of 253 self-harming patients admitted to emergency units in Northern Uganda in 2021. Twenty-two (8.7%) died by suicide, especially due to organophosphate poisoning (n = 14, 63.6%). Regarding self-harm management, observed differences were noted in the type of hospital and the use of antidotes between public and private facilities. There is a need for more studies and a multisector approach to prevent and treat self-harm in Uganda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Short communication

Intentional self-harm is a global public health crisis that requires urgent attention. Every year, millions of people harm themselves intentionally, often with fatal consequences [1, 2]. Self-harm is one of the main reasons for emergency hospital admissions worldwide [3]. Many of these patients die at the emergency department (ED), while others survive but face a high risk of suicide or repeated self-harm [4]. These repeated attempts further increase the demand for the desired services and resources. Self-poisoning is a prevalent method of intentional self-harm worldwide, with varying incidence rates and patterns across regions [5, 6]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, studies from several African countries, including Egypt and Uganda, revealed alarming trends in suicide attempts and fatalities due to self-poisoning [7,8,9]. These rates were notably higher among young adults and were linked to socio-economic pressures, mental health issues, and interruptions in healthcare services [7, 8].

In Uganda, a low-income country with a fragile health system especially in post-conflict northern region, self-harm poses a serious challenge. The health sector, especially mental health, is underfunded and understaffed, making it difficult to provide adequate care for self-harm patients and prevent ED visits [10]. To worsen the situation, the speciality of emergency medicine is a juvenile profession, with most of its services relying on general practitioners. Hospital supplies, such as antidotes for many agents that are commonly used in self-harming, have chronically been inadequate in the country, potentially leading to many preventable deaths [11, 12]. For example, in 2020, over one in six self-harm related hospital visits in Southwestern Uganda resulted in death [9].

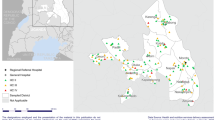

To understand the system's needs and future projections, studies on the burden of self-harm and its related factors provide insight into the situation. Various studies have shown prevalent levels of self-harm and suicide in many parts of Uganda, affecting various groups of people [9, 13,14,15]. However, there is a lack of research on this issue, especially in northern Uganda. A region grappling itself out of a long-standing war and unsettlement in the neighbouring countries, in the background of very high poverty levels [16,17,18,19,20]. Moreover, no studies have focused on the EDs that deal with the most severe cases of self-harm. Therefore, this study aimed to identify patterns and outcomes of individuals admitted for intentional self-harm in Northern Uganda, thus, providing insights into systemic needs and guiding effective interventions and resource allocation to reduce self-harm in this vulnerable population.

We conducted a prospective analysis to assess poisoning cases in two Northern Uganda’s emergency units [21]. For the present analysis, we included individuals admitted after episodes of intentional self-harm and excluded those admitted for accidental ingestion, non-self-inflicted harm, follow-up care, or non-emergency reasons to ensure the study focused on acute self-harm incidents.

In the analysis of the 253 patients, most were young males, treated at a private facility. Alcohol-related self-harming [i.e., deliberately use of alcohol as a method of self-harm] (44.7%) was the commonest method of self-harming, followed by organophosphate poisoning (31.2%), and medications/drugs overdose (9.9%). Almost two-thirds of the patients who self-harmed did not receive any antidotes, and 8.7% died (Table 1).

When examining the types of poisons, there was a clear predominance of organophosphates and medication/drug use among females compared to males. In contrast, alcohol was significantly predominantly used by males than females (S1 Table 1).

Death was more likely among patients who used organophosphates, who were admitted to private facilities, and who received potential antidotes. A statistically significantly higher proportion of individuals received antidotes in the private facility than in the public facility (41.6% vs. 22.8%; p = 0.003). However, the private hospital admitted most of the patients with organophosphate and drug overdose, while the public facility was dominated by alcohol-related self-harm (S1 Table 2).

This study revealed the prevalence of suicide following intentional self-harm at 8.7% with clear predominance of organophosphate poisoning and medication/drug use among females. Death was higher among patients who used organophosphates, who were treated at private facilities, and received antidotes. Compared to private hospitals, alcohol-related self-harm was more common at the public facility.

The prevalence of suicide reported in this study was much higher than the national suicide prevalence rate in 2019 (4.6%) [22]. However, the rate was lower than 16.6% from selected health facilities in Southwestern Uganda during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period that was characterized by increased rates of suicide [9]. In contrast, the present study, the reported prevalence rates in Southwestern Uganda exclude self-harm cases from resource-rich tertiary hospitals that may potential access to antidotes to commonly used items for self-harming by many Ugandans, such as atropine, thus, potentially affecting overall prevalence rates [23].

The observed higher mortality secondary to the use of organophosphate is likely attributed to delays in reaching the hospital, lack of antidotes and resuscitation resources, and potentially overwhelming workload to the already few staff in the EDs. Ugandans have predominantly used organophosphates in self-harming due to easy access in an agriculture-dependent economy [9]. The high burden of this problem and the lack of resources in public-funded hospitals may be the driver to many individuals receiving services from private hospitals—which may have most of the needed resuscitation resources and antidotes. Uganda is among the countries with the highest alcohol-consuming countries in Africa, with the poor mainly engaging in excessive use [24]. Many crude forms of alcohol are available, and individuals struggling with various stressors may opt to “drink down their problems” [24]. The demographic of such individuals may not afford private services, thus their high numbers in public facilities.

To prevent these unnecessary deaths, Uganda needs to invest more in health care, especially mental health, and emergency care services. We recommend that EDs be supplied with adequate antidotes, that organophosphates and other dangerous drugs be regulated more strictly, and that mental health services be expanded for people who self-harm or have suicidal thoughts. We also suggest that efforts be made to reduce poverty and alcohol use, which are linked to self-harm and suicide. In conclusion, we call for a multisectoral approach to address self-harm as a growing public health issue in Uganda.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be provided upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(6):902–9.

Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM. 2000;93(11):715–31.

Sara G, Wu J, Uesi J, Jong N, Perkes I, Knight K, O’Leary F, Trudgett C, Bowden M. Growth in emergency department self-harm or suicidal ideation presentations in young people: comparing trends before and since the COVID-19 first wave in New South Wales, Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2022;57(1):58–68.

Aaltonen K, Sund R, Hakulinen C, Pirkola S, Isometsä E. Variations in suicide risk and risk factors after hospitalization for depression in Finland, 1996–2017. JAMA Psychiat. 2024;81:506.

Mew EJ, Padmanathan P, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Chang S-S, Phillips MR, Gunnell D. The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006–15: systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:93–104.

Prosser JM, Perrone J, Pines JM. The epidemiology of intentional non-fatal self-harm poisoning in the United States: 2001–2004. J Med Toxicol. 2007;3:20–4.

Elhawary AE, Lashin HI, Fnoon NF, Sagah GA. Evaluation of the rate and pattern of suicide attempts and deaths by self-poisoning among Egyptians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Toxicol Res. 2023;12(6):1113–25.

Kasemy ZA, Sharif AF, Amin SA, Fayed MM, Desouky DE, Salama AA, Abo Shereda HM, Abdel-Aaty NB. Trend and epidemiology of suicide attempts by self-poisoning among Egyptians. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(6): e0270026.

Kaggwa MM, Rukundo GZ, Wakida EK, Maling S, Sserumaga BM, Atim LM, Obua C. Suicide and suicide attempts among patients attending primary health care facilities in Uganda: a medical records review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;15:703–11.

Kaggwa MM, Harms S, Mamun MA. Mental health care in Uganda. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(10):766–7.

Nabukeera MS. Challenges and barriers to the health service delivery system in Uganda. 2016.

Tusubira AK, Akiteng AR, Nakirya BD, Nalwoga R, Ssinabulya I, Nalwadda CK, Schwartz JI. Accessing medicines for non-communicable diseases: patients and health care workers’ experiences at public and private health facilities in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7): e0235696.

Arinaitwe I, Kaggwa MM, Kajjimu J, Kule M, Muwanguzi M, Najjuka SM, Nduhuura E, Rukundo GZ. Suicide among Ugandan university students: evidence from media reports for 2010–2020. BJPsych International. 2021;18(3):63–7.

Kaggwa MM, Mamun MA, Najjuka SM, Muwanguzi M, Kule M, Nkola R, Favina A, Kihumuro RB, Munaru G, Arinaitwe I, et al. Gambling-related suicide in East African Community countries: evidence from press media reports. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):158.

Abaatyo J, Favina A, Bulega SE, Kaggwa MM. Suicidal behavior among inpatients with severe mental conditions in a public mental health hospital in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):346.

Hwang T-J, Rabheru K, Peisah C, Reichman W, Ikeda M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1217–20.

Buecker S, Horstmann KT. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Psychol. 2022;26:272.

Giebel C, Ivan B, Ddumba I. COVID-19 public health restrictions and older adults’ well-being in Uganda: psychological impacts and coping mechanisms. Clin Gerontol. 2022;45(1):97–105.

Najjuka SM, Checkwech G, Olum R, Ashaba S, Kaggwa MM. Depression, anxiety, and stress among Ugandan university students during the COVID-19 lockdown: an online survey. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(4):1533–43.

Kizza D, Hjelmeland H, Kinyanda E, Knizek BL. Alcohol and suicide in postconflict Northern Uganda. Crisis. 2012;33(2):95–105.

Opiro K, Amone D, Wokorach A, Sikoti M, Bongomin F. Acute poisoning emergencies at Gulu university teaching hospitals in Northern Uganda: prevalence, outcomes and clinical challenges. East Afr J Health Sci. 2024;7(1):34–45.

Uganda Suicide Rate 2000–2024 https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/UGA/uganda/suicide-rate.

Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Priority setting in developing countries health care institutions: the case of a Ugandan hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:1–9.

ALLIANCE UAP: UGANDA ALCOHOL STATUS REPORT–2018. 2018.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of St. Mary’s Hospital, Lacor and Gulu Regional Referral Hospital. The participants and the dedicated research assistants.

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.K. and J.A. wrote the main manuscript text and J.A prepared tables. M.M.K, J.A, K.O, M.S and F.B reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.The study protocol was approved by Lacor Hospital Internal Review Ethical Committee (LHIREC), review number LHIREC Admin. 005/04/2022. Administrative clearances were also obtained from the administrators of St. Mary’s Hospital, Lacor and Gulu Regional Referral Hospital. Participation in the study was voluntary from participants and informed written consent was mandatory before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaggwa, M.M., Abaatyo, J., Opiro, K. et al. Patterns and outcomes of individuals admitted at emergency units following intentional self-harm in Northern Uganda. Discov Ment Health 4, 59 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00115-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00115-z