Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of music therapy with songwriting on mental health of vulnerable women and men in a conflict-ridden setting. We examine the impact on participants’ mental health (specifically anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms), the extent to which improvement was sustained for an extended period of time, and whether there were gender differences in improvement. Such an assessment is central in appraising the strength and relevance of mental health services offered to vulnerable populations in conflict-ridden settings.

Methodology

This study is a longitudinal mixed method evaluation of music therapy with songwriting comparing mental health symptoms of participants before and after exposure to the program rather than a clinical trial with a control group. Participants in the Healing in Harmony (HIH) program were screened for anxiety, depression and PTSD before treatment, immediately after treatment and 6 months later. The Hopkins Symptoms checklists were used to evaluate anxiety and depression among 128 women and 60 men exposed to the HIH program from April to August 2021 in Mulamba in eastern DRC. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire was used to measure post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Average scores range from 1 to 4, with higher values indicating higher levels of the symptoms. Participants were classified as positive for each outcome when they scored equal to 1.75 or higher for anxiety and depression, and 2.5 or higher for PTSD. The qualitative component of the study draws from four focus group discussions (FGDs), two of which were conducted immediately after treatment and two six months later to gain an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences with the HIH.

Results

At the aggregate level, the rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD before treatment among participants were respectively 91.4, 90.4 and 36.7%. Immediately after treatment, the rates dropped significantly to 14.3, 15.9 and to 2.1%, respectively. The mean scores of the three mental health disorders were high before treatment but dropped significantly after treatment. The aggregate mean scores for anxiety, depression, and PTSD before and after treatment were 2.55 vs 1.29, p < 0.001, 2.38 vs 1.35, p < 0.001 and 2.27 vs 1.30, p < 0.001, respectively. The only statistically significant difference between men and women was the mean score of depression before treatment (women 2.44 vs men 2.24, p < 0.05). Both men and women demonstrated statistically significant improvement in mental health immediately after treatment across all categories (p < 0.001). Six months after treatment, aggregate scores show that improvement was sustained across all categories. For depression and PTSD, scores showed a small but statistically significant improvement over the immediate post-treatment scores (by 0.03 and 0.01, respectively, p < 0.05), while anxiety scores showed a small but statistically significant increase in symptoms (by 0.16, p < 0.05). Although women appear to show signs of greater and longer-lasting improvement compared to men, these differences are not statistically significant. Findings from the qualitative component of the study suggest that men’s inclusion in psychosocial rehabilitation programs previously designed for women is crucial in our efforts to establish trauma-free environments, and for constructing healthy gender relationships across time and space.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that the HIH program improves mental health disorders for both women and men, and that including men in a program originally designed for women might enhance mutual understanding between women and men contributing to effective and sustainable healing. Clinical trials are needed for future research to examine the impact of men’s inclusion in women’s originally designed mental health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Armed conflict and poverty are major sources of economic instability and social disruption with significant adverse mental health effects on survivors [1, 2]. The most prevalent mental health challenges include but are not limited to anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3]. Symptoms include distressing memory intrusions, avoidance, social isolation, emotional disturbance, hyper-arousal, lack of sleep etc. Lund et al. [2], show that people with the lowest incomes in a community suffer 1.5 to 3 times more frequently from depression, anxiety and other common mental disorders than those with the highest incomes; and armed conflict worsens or exerts increased devastating mental health effects on affected populations [4]. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), one of the several effects of armed conflict, often causes survivors to develop a complex and negative self-image, along with warped perceptions of the gender tied to their abusers. This can reinforce harmful stereotypes and complicate broader gender relations. However, this nuanced impact remains under-researched in the context of post-trauma recovery and social reintegration.

Interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and psychotherapy have proven effective in addressing anxiety, depression and PTSD [5, 6]. Data from high-income country studies suggest that the effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy may be sustained for more than 1 year post treatment [5, 7]. Similarly, Dugas et al. [8] found that more than half of the participants in a cognitive behavioural treatment program remained asymptomatic 2–14 years post therapy. However, these methods might be hard to implement in contexts characterized by armed conflict and poverty, and there is an ongoing academic debate regarding which interventions are effective in reducing mental health burdens, while addressing toxic gender relations in low- and middle-income countries [7].

Music therapy is a unique intervention that not only addresses mental health conditions but also offers a powerful platform for exploring and healing genderrelated dynamics in a sensitive and inclusive way. While it is often used in combination with other therapeutic approaches, music therapy stands out for its ability to foster emotional expression selfdiscovery and empowerment through creative and nonverbal means; this makes it particularly valuable for addressing mental health issues in a gendersensitive and genderinclusive manner [9]. Several studies demonstrate that music therapy is effective in addressing anxiety, depression, and PTSD, as well as in supporting rehabilitation from stroke and other chronic conditions such as Alzheimer’s diseases (e.g. [10,11,12]). However, there are many variants of music therapy but the most used are improvisational and songwriting music therapies [13, 14]. In the former the therapist and the client co-create music during a particular moment to express her/his current emotions [13]. Musical improvisation is performed through singing or playing thereby producing extemporaneously a melody, rhythm, song, or an instrumental piece. Songwriting includes various techniques in which clients are assisted, either individually or in groups, to create lyrics, and perform or record their own songs [15]. Both improvisational and songwriting music therapies have proven efficient in addressing mental conditions including anxiety, depression and PTSD [16]. Music exerts an immediate positive impact on the mood, and singing together in groups can promote social bonding [16].

According to Chanda and Levitin [17], music can lead to the release of endorphins to the brain, boosting positive feelings while reducing fear and sadness, improving one’s overall emotional state [17]. Hermandez-Ruiz et al. [18] examine the effects of music therapy on symptoms associated with anxiety and PTSD. Their study compares a randomly selected experimental group that went through the music therapy to a control group that received no therapy. Results show that the music therapy group showed a greater pre–post reduction in anxiety and improvement of sleep quality, providing robust evidence to the therapeutic property of music [18].

According to Keolesch [11], music can automatically capture attention and distract from negative experiences such as pain, anxiety, worry and grief by modulating activities of limbic and para limbic brain structures involved in the initiation, generation, maintenance, termination, and modulation of emotions. Anxiety, depression and PTSD are partly related to dysfunction of limbic and para-limbic structures of the brain [11]. Although music therapy with songwriting can improve functioning among individuals with trauma exposure and PTSD, more rigorous empirical research is needed to measure its longer-term effects on mental health disorders [9, 10]. Moreover, little is known about whether music therapy with songwriting works equally well across different population groups, including vulnerable women and men. In particular, there is a dire need for a study that includes both women and men as both are emotionally affected by the impacts of wars and poverty [19].

The eastern part of the DRC has repeatedly experienced protracted conflicts since 1996 [20] resulting in complex forms of gender-based violence , forced displacement, massacres, impoverishment and generalized insecurity [21, 22]. Conflict-affected communities are particularly challenging contexts in which mental health programs are highly needed given the complexity of the physical and mental health conditions resulting from armed conflicts, loss, and forced displacement [23].

A study by Cikuru et al. [9] examines the impact on mental health of a music therapy program with songwriting (HIH) designed for female survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in the Democratic Republic of Congo. While the study showed promising results, some participants noted that others in the community believed that participating in the program signified that the woman had been raped, which was seen as a stigma for both the woman and her family [9]. Moreover, during the initial screening period, requests were made for a program aimed at men. In response, the HIH program was subsequently opened to both women and men in order to meet their emotional needs and further contribute to a community-based approach to mental health. The inclusion of men to the program provides an ideal setting to examine the extent to which the program works equally well for men.

The current study builds on findings from [9] and uses an explanatory mixed-method approach to examine the impact of introducing men to the previously women-only program, as well as expanding the target group from those suffering from SGBV to any kind of trauma related to poverty and conflict. We draw from empirical data collected in Mulamba in eastern DRC in 2021 to assess the effectiveness of music therapy with songwriting in reducing anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms in vulnerable populations before treatment, immediately after treatment, and 6 months post treatment. We examine gender differences in both symptoms’ levels before and after the program. Such an assessment is crucial in our efforts to grasp the strength and relevance of mental health interventions in armed conflict contexts and poverty. However, it is worth mentioning that this study is an evaluation of a music therapy songwriting program, comparing the mental health symptoms of women and men before and after exposure, rather than a clinical trial with a control group, which was not formed due to time and logistical constraints.

2 Overview of the Healing in Harmony Program

Music therapy with songwriting is one of the many therapeutic approaches used at Panzi Foundation DRC in eastern DRC to address mental health effects of GBV, and other trauma [9]. Panzi Foundation DRC is a non-profit created in 2008 by the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Doctor Denis Mukwege to provide holistic care, including medical, psychological, socioeconomic and legal support to survivors of SGBV [24, 25]. Since 2015, music therapy at Panzi Foundation DRC has been offered through the HIH program.

HIH works with a clinical psychologist and a music producer to provide music therapy with songwriting to participants with various mental health disorders [9]. The program was established by Make Music Matter, a Canadian organization that uses the power of music to address various forms of mental health disorders, including symptoms associated with anxiety, depression and PTSD [26].

The therapeutic process begins by writing down stories about a personal or group traumatic experience. These stories are then turned into songs and are recorded with the support of a music producer, resulting in well-tuned lyrics about their emotions and experiences with a personal or group traumatic event [9]. When a story is produced or written, the music producer starts composing an instrumental accompaniment eventually creating a song performed individually or in groups. While music is used for therapeutic ends, it also helps participants develop their musical artistry.

The HIH is a group therapy which runs for 12 weeks, and participants are expected to attend therapeutic sessions twice a week for at least 2 hours. During the period of this study, HIH recruited both women and men who identified themselves as poor, and vulnerable to multi-type violence. Causes of trauma cited by the participants included armed insecurity, sexual violence, poverty, polygamy, domestic violence and death of loved ones.

3 Methods

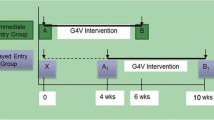

This study employs a longitudinal, explanatory sequential mixed-methods design [27] where quantitative data collection was conducted first, followed by qualitative data collection after participants completed the HIH program. The qualitative component aimed at elaborating on the quantitative results in order to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of a broader recruitment, which included both women and men.

Participants were recruited to the HIH program through the community mobilization staff of Panzi Foundation DRC who went into communities in Mulamba to inform people about the program. Anyone who identified themselves as a poor or vulnerable person could register for the pre-treatment survey which used the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist to assess anxiety and depression [28, 29] and the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire to measure PTSD[30, 31]. To be eligible for the program, a participant had to have a conventional minimum score of 1.75 for either anxiety or depression [28] or a minimum score of at least 2.5 for PTSD [30, 32]. To be included in the study, the participant had to complete the program. A total of 217 persons, of whom 140 were women and 77 men, were screened, but not all of them were able to complete the program for various reasons including but not limited to travel, displacement, death etc. The quantitative component of the study includes only the 188 individuals (128 women and 60 men) who completed the program at Mulamba Hospital in eastern DRC and were surveyed before, after treatment, and 6 months post treatment (April 2021, August 2021, and March 2022, respectively).

Although the quantitative data show that participants suffered from mental health disorders before the program and experienced an improvement in their scores after treatment, the statistics provide no insight into how improvement was experienced and explained by the participants after their participation in the HIH program. Two FGs were conducted immediately after treatment, and two six months post treatment. Participation in the qualitative component was contingent on having tested positive for at least one of the three mental health disorders before treatment, proximity to the interview site, and being available for interview.

Each focus group (FG) included 7 to 10 participants, both women and men, who completed the full program. Data collection took place at Mulamba Hospital, in a setting that ensured confidentiality. Approximately 60 participants live within a 20-minute walk from the hospital, of which 37 were able to attend the focus groups. Of these, 70% were women and 30% were men. The FGDs were conducted in Swahili, the vernacular language of eastern DRC, and lasted between one and a half to two hours, depending on the participants’ responses. Participants were asked about the impact of the program and their reasons for believing it was effective.

Data collection adhered to ethical standards for research involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained prior to conducting interviews. Participants were also made aware of their right to withdraw from the study or skip any questions they felt uncomfortable answering. Additionally, they were informed that the study was conducted for academic purposes and that their identities would be protected throughout the research process.

As researchers have been affiliated with Panzi Foundation in various capacities, two main steps were taken to ensure the objectivity of the study. First, the surveys were conducted by 10 external and independent enumerators, all holding university degrees in clinical psychology. Second, the enumerators received training before each data collection period and were instructed to rely solely on the participants' responses, regardless of the outcome. Emphasis was placed on independent data collection to better evaluate the relevance of mental health interventions. While there are numerous mental health intervention programs at Panzi, evidence is needed to determine which programs are effective.

3.1 Data management and analysis

Quantitative data were collected from structured questionnaires through open data kits (ODK) and were then uploaded and cleaned into Excel 2016. Data from Excel were then imported into Stata 14.0 software (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) for analysis. Average anxiety, depression and PTSD scores were obtained by dividing the total score by the number of questions answered, average scores ranged from 1 to 4, with higher values indicating higher levels of mental health symptoms. Participants were classified as positive for each outcome when they scored equal to 1.75 or higher for anxiety and depression and 2.5 or higher for PTSD [30, 31].

To describe the data, we used the means and their standard deviation (SD) for symmetric distributions and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables for skewed or anomalous distributions. Categorical variables were summarized in frequencies and percentages. To compare means, we used the student t-test for paired samples (before and after music therapy) and (before and 6 months after music therapy). The comparison of proportions was done with the Pearson chi-square test or the Fisher exact test for proportions less than or equal to 5. All p values were two-sided.

All interviews were recorded, transcribed into English, and subjected to thematic analysis, which involved identifying, analyzing, and interpreting patterns in qualitative data. The first author initially read through all the transcripts and field notes, generating initial codes and themes inductively. The data were then reread several times, and the themes were further developed. To ensure the validity and trustworthiness of the qualitative data, the third and tenth authors reviewed the proposed themes against the transcripts and suggested additional themes. The authors organized two meetings during which where they agreed on the selection of specific themes that fit the scope of this study and chose specific quotes from the data to illustrate the gendered lived experiences of participants and their intersubjective explanations of why the program worked.

4 Results

4.1 Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic profiles of the participants. The median age was 35 (17–71) years and 33.5% were 28–38 years. The majority were women (68.1%) compared to 31.9% men. Most participants (79.8%) were married, 29.8% have not been at school, 39.3% had primary education. Most participants were farmers (77.1%), 23.9% were engaged in small businesses. 37.8% were internally displaced persons and 34% were survivors of sexual violence.

4.2 Symptoms of anxiety, depression and PSTD before and after treatment and 6 post treatment

Table 2 presents the symptoms levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD, before and after music therapy, and 6 months later post treatment at the aggregate level. The rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD before treatment were 91.4, 90.4, and 36.7%, respectively. After treatment, a significant decline was observed in these mental health disorders, dropping down to 14.3, 15.9, and to 2.1%, respectively. Six months after participation in the HIH program, the rates of the three mental health symptoms were still low among the participants: r 26.5, 21.8 and 1.0%, respectively, suggesting that the symptoms were alleviated for an extended period for most participants.

4.3 Mean scores comparison of anxiety, depression and PTSD before and after treatment

Table 3 compares mean scores of anxiety, depression and PTSD before and after treatment. The mean scores of the three mental health disorders were high before treatment but dropped significantly after treatment. Mean scores for anxiety, depression, and PTSD before and after treatment were 2.55 vs 1.29, p < 0.001, 2.38 vs 1.35, p < 0.001 and 2.27 vs 1.30, p < 0.001, respectively. After 6 months, most participants generally still showed a significant improvement from their pre-treatment scores.

4.4 Gender disaggregated mean scores of anxiety, depression and PTSD before, after and 6 months post treatment

Table 4 shows that, before treatment, only depression had a statistically significant gender difference with women showing more symptoms of depression than men. Before music therapy the mean scores for anxiety were 2.58 for women versus 2.46 for men; for depression, 2.44 for women versus 2.24 for men; and for PTSD, 2.28 for women versus 2.44 for men. However, data show that mean scores dropped significantly after treatment for both women and men across all categories (anxiety mean score = 1.30 for women vs 1.27 for men; depression mean score = 1.33 for women vs 1.38 for men; PTSD mean score 1.29 for women vs 1.32 for men).

The gender-disaggregated mean scores 6 months post-treatment were as follows: 1.36 for women versus 1.63 for men in anxiety; 1.30 for women versus 1.36 for men in depression; and 1.28 for women versus 2.46 for men in PTSD. Although the table shows no statistically significant gender differences, there are indications that men tend to have lower anxiety and depression levels before treatment, while women experience more significant improvements post-treatment, with these improvements appearing to last longer. PTSD mean score for women remains lower 6 months after therapy (1.28) compared to the pre-treatment level (2.28). In contrast, there is a slight increase in the PTSD mean score for men 6 months post-treatment (2.46) compared to the pre-treatment level (2.24). This slight increase for men may be explained by complex factors beyond the scope of the program, such as the ongoing economic crisis and insecurity.

Table 5 shows intra-gender disaggregated mean score of women versus men before and after participation in music therapy. Both men and women show a statistically significant drop in scores across all categories after music therapy.

4.5 Impact of the HIH program on mental health

Both women and men reported increased feelings of self-worth. One female participant explained, “Before the program, I felt stressed and thought I was a useless person, but now I feel stronger and have become happy again.” Similarly, one male participant said, “I feel like a human being among others now, and I am proud of myself,” while another said, “I thought I was a ‘failed man’ when my wife was raped, but I am feeling okay now. I can work and live in peace with my family again.”

Several of the participants also pointed to the enjoyment they gained from the therapy itself. For example, one woman noted that, ‘’Singing and dancing with others in music therapy turned my negative emotions of despair and headache into hope and joy.’’ She continued, ‘’I was not able to sleep, I lost my ability to sleep and used to feel as though I was outside of myself, but I began to feel better after music therapy.’’

4.6 Explaining emotional healing

Most participants attributed the improvement in their mental health to the discovery of persons with similar traumatic experience within the HIH program, to verbalisation of traumatic experiences through songs, to the inclusion of men and women in a dynamic gender-inclusive music program, and to the expertise of the music therapist. One female participant remarked that “in music therapy, you discover that the others also went through rape but survived, then you say that you are not alone.” Understanding that traumatic events are common and were not unique to a person was seen as leading to acceptance of the problem and of oneself: “when you are in group therapy, you realize that someone has died in everyone’s family, and you accept the situation the way it is,” said a male participant. According to some participants, the symptoms of trauma are intense if someone has no space to express what happened to them. “When you turn your story into a song and speak out, you start feeling well emotionally,” said another female participant. “The melody that you listen to in the studio heals the wounds of our spirits,” commented another.

Several of the participants noted that having both men and women in the program increased their sensitivity to one another. A male participant said, “When you come to the HIH program you will no longer beat your wife. You change your mind about what it means to be a man because the music therapy teaches you positive masculinity.” A female participant also pointed out, “When he comes to the program, he will no longer be insulting or oppressing you.” Some male participants also mentioned that taking the program along with women was constructive: “When we take music therapy together, we understand each other’s problems and start being respectful to each other.”

Finally, several participants pointed out that they were able to overcome trauma because they had a good psychologist with a sense of humour who understood their problems without judgment and who provided good pieces of advice for change, adaptation and survival in difficult circumstances: “When you see him, you feel comfortable talking about your problem and learn how to live a new life.”

5 Discussion

Findings suggest that adding men to a music therapy program that was originally designed to target only women who had suffered from SGBV does not threaten the success of the program, and in some ways could augment the success by building bridges between men and women. Both men and women saw significant improvement in mental health after participating in music therapy with songwriting and experienced a significant reduction of anxiety, depression and PTSD, while creating connections that address gender disparities. These results corroborate the findings from previous studies (e.g., Cikuru et al. [9]), that show significant improvements in symptoms associated with anxiety, depression and PTSD after participation in music therapy.

Our study, however, seemed to show an even greater degree of short-term improvement than was found in Cikuru et al. [9]. In comparing changes of anxiety symptoms at initial screening and immediately after treatment, for example, we found an improvement of 77.1 percentage points compared to 36.2 percentage points found by [9]. The higher level of improvement was also reflected in the long-term scores, even though Cikuru et al. [9] took the second survey after only 3 months while ours took place after 6 months post treatment. Qualitative data also suggest that adding men to a program designed originally for women may further improve the success rates of a women-only program. Moreover, our long-term success rates were comparable to those found by Resick et al. [33] who used cognitive-processing therapy for depression and PTSD symptoms for female survivors of sexual violence.

Although Koelsch [11] posits that the effectiveness of music therapy can be explained by its capacity to capture attention and distract it from negative experiences, and to modulate activities of limbic and para limbic brain structures, the qualitative data in this study suggest complex factors at work including active verbalization of one’s traumatic experiences in a song and the inclusion of gender dynamics in the therapeutic processes. Participants also noted the importance of not feeling alone in the experience of trauma and the ability of the therapist to win their trust. These findings are consistent with Landis-Shack et al.[10], who show that complex social, cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms explain music therapy efficacy. Although men can also face SGBV in armed conflicts, most of this phenomenon is perpetrated by male perpetrators. Qualitative data suggest that, men may stop engaging in aggressive behaviour after participating in a gender inclusive program, which may also lead to fast remission and long-term maintenance of emotional balance.

6 Conclusion

Both quantitative and qualitative data suggest that the HIH program is associated with significant improvement of mental health symptoms for vulnerable individuals, both women and men, in armed conflict settings. Men’s inclusion in psychosocial rehabilitation programs originally designed for women was seen as crucial in our efforts to establish trauma-free environments. Men's inclusion was also seen as essential for ensuring effective and sustainable recovery from mental health disorders and for fostering healthy gender relationships across time and space. Future research needs to focus on how music therapy affects women and men considering the nature of their relationship’s husbands, bothers, fathers, cousins, in laws, community members etc.

7 Study limitations

While participation in the HIH program seems to have significantly contributed to the reduction of mental health symptoms among the participants, other factors might have facilitated their emotional stabilization but were not controlled due to the lack of a control group. As mentioned earlier, the HIH program is part of a broad holistic care program offering medical, psychological, socioeconomic and legal support to survivors of SGBV. Some participants might have benefited from other forms of supports during music therapy which might have positively affected their mental health.

Data availability

The data are not registered in an online data repository. The data supporting the findings of this study are available only in a saved file in. XLS format and will be available upon request to the corresponding author after publication.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

22 March 2025

The original online version of this article was revised to correct typographical and grammatical errors.

References

Banks LM, Kuper H, Polack S. Poverty and disability in low-And middleincome countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189996.

Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R, Corrigall J, Joska JA, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:517–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027.

Murphy JM, Olivier DC, Monson RR, Sobol AM, Federman EB, Leighton AH. Depression and anxiety in relation to social status: a prospective epidemiologic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:223–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270035004.

Bolton P, Betancourt TS. Mental health in postwar Afghanistan. JAMA. 2004;292:626–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.5.626.

DiMauro J, Domingues J, Fernandez G, Tolin DF. Long-term effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders in an adult outpatient clinic sample: a follow-up study. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:82–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.10.003.

Morina N, Malek M, Nickerson A, Bryant RA. Meta-analysis of interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in adult survivors of mass violence in low- and middle-income countries. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:679–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22618.

Bass JK, Murray SM, Lakin DP, Kaysen D, Annan J, Matabaro A, et al. Maintenance of intervention effects: long-term outcomes for participants in a group talk-therapy trial in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Glob Ment Heal. 2022;9:347–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.39.

Dugas MJ, Koerner N, Robichaud M. Cognitive behavior therapy targeting intolerance of uncertainty: application to a clinical case of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2013;19:251–63. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.19.1.61.66326.

Cikuru J, Bitenga A, Balegamire JBM, Salama PM, Hood MM, Mukherjee B, et al. Impact of the healing in harmony program on women’s mental health in a rural area in South Kivu province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Glob Ment Heal. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.11.

Landis-Shack N, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO. Music therapy for posttraumatic stress in adults: a theoretical review. Psychomusicol Music Mind, Brain. 2017;27:334–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000192.

Koelsch S. A neuroscientific perspective on music therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1169:374–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04592.x.

Carr C, D’Ardenne P, Sloboda A, Scott C, Wang D, Priebe S. Group music therapy for patients with persistent post-traumatic stress disorder—An exploratory randomized controlled trial with mixed methods evaluation. Psychol Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 2012;85:179–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02026.x.

Erkkilä J, Gold C, Fachner J, Ala-Ruona E, Punkanen M, Vanhala M. The effect of improvisational music therapy on the treatment of depression: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-50.

Baker F, Wigram T, Stott D, McFerran K. Therapeutic songwriting in music therapy: part I: who are the therapists, Who are the clients, and why is songwriting used? Nord J Music Ther. 2008;17:105–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098130809478203.

Baker FA. Front and center stage: participants performing songs created during music therapy. Arts Psychother. 2013;40:20–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.09.004.

Carr CE, Millard E, Dilgul M, Bent C, Wetherick D, French J, et al. Group music therapy with songwriting for adult patients with long-term depression (SYNCHRONY study): a feasibility and acceptability study of the intervention and parallel randomised controlled trial design with wait-list control and nested process evalua. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023;9:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-023-01285-3.

Chanda ML, Levitin DJ. The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:179–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007.

Hernández-Ruiz E. Effect of music therapy on the anxiety levels and sleep patterns of abused women in shelters. J Music Ther. 2005;42:140–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/42.2.140.

Alexandre AB, Rutega B, Byamungu PA, Notia CA, Alldén S. A man never cries: barriers to holistic care for male survivors of sexual violence in eastern DRC. Med Confl Surviv. 2022;38:116–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2022.2056211.

Vlassenroot K, Huggins CD. Land, Migration and Conflict in Eastern D.R. Congo. Eco-Conflicts 2013;3:1–4.

Alexandre AB. Individual agency and social support in healing from conflict-related sexual violence: a case history from eastern DRC. Glob Pub Health. 2024;19:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2024.2308717.

Spittaels S, Hilgert F. Mapping conflict motives: Eastern DRC. Antwerp IPIS 2008:1–44.

Kasherwa AC, Alexandre AB, Mugisho GM, Foussiakda AC, Balegamire JB. The roles and ethics of psychosocial support workers in integrated health services for sexual and gender-based violence survivors. J Soc Work. 2023;23:586–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173221144551.

PANZI F. Rapport annuel des activités de la fondation PANZI 2018:20–31.

Le modèle - Fondation Panzi n.d. https://panzifoundation.org/fr/the-model/. Accessed 5 June 2023.

Healing in Harmony - Make Music Matter n.d. https://makemusicmatter.org/healing-in-harmony/. Accessed 5 June 2023.

Berman E. An exploratory sequential mixed methods approach to understanding researchers’ data management practices at UVM: integrated findings to develop research data services. J EScience Librariansh. 2017;6: e1104. https://doi.org/10.7191/jeslib.2017.1104.

Ottisova L, Hemmings S, Howard LM, Zimmerman C, Oram S. Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: an updated systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:317–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000135.

Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, Girling AJ, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2015;350:h391–h391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h391.

Shoeb M, Weinstein H, Mollica R. The Harvard trauma questionnaire: adapting a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in Iraqi refugees. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:447–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007078362.

Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The harvard trauma questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:111–6.

Sharma M, Koenen KC, Borba CPC, Williams DR, Deng DK. The measurement of war-related trauma amongst internally displaced men and women in South Sudan: psychometric analysis of the harvard trauma questionnaire. J Affect Disord. 2022;304:102–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.016.

Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:867–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.867.

Acknowledgements

Our deepest thanks go to our participants and to Lynn Nygaard from Peace Research Institute, Oslo who provided excellent editing assistance. John quattrochi from GeorgeTown University and Susanne Allden from Linnaeus University provided constructive comments for the improvement of this paper. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of our institutions, and any errors in the text are ours alone.

Funding

This research was funded by Fund for Innovation and Transformation, Manitoba Council for International Cooperation and Global Affaires Canada, project number 150-1902.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions. Conceptualisation: AAB, AKC, JBB, DMM; Methodology: AAB, DM, AK, JB, JYT, LOM. Formal analysis and Investigation: MOR, AAB, CAK, PAB, LOM, MMH, JYT, AAB, GMM; Original draft preparation: AAB, DMM; Writing, review and editing: AAB; JYT, CAK, JBB, DMM. Supervision: all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data was collected in line with ethical norms for research involving human subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to data collection, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the South Kivu Provincial Ethics Committee in March 2021 and registered under CNES001/DPSK/182PM/02021. Informed consent was collected from participants at each period of data collection. For illiterate persons participating in the study, an informed consent from an adult literate family member was obtained in addition to an oral consent provided by the person herself /himself.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexandre , A.B., Kasherwa, A., Balegamire, J.B. et al. Bouncing back after trauma: music therapy, gender, and mental health in conflict-ridden settings. Discov Ment Health 5, 15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-025-00137-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-025-00137-1