Abstract

Background

Refugees and other New Americans faced unique mental health barriers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reduced access to mental health supports and services in this population indicates a need for new community-based mental health interventions.

Aims

This paper explored refugee parents’ and young adults’ perceptions of the mental health barriers and facilitators encountered by young resettled refugees (ages 10–24) and their parents.

Methods

Using an interpretive phenomenology approach and a form of community-based participatory research (CBPR), we designed a focus group guide with student community members from various refugee and immigrant communities. We held eight gender- and language-concordant focus groups with refugee parents, and four gender-concordant focus groups with refugee young adults (18–24), facilitated by student community members. Translated transcripts were analyzed for major themes using an iterative emergent thematic coding approach.

Results

The conversations in these focus groups were wide-ranging. Here we explore the themes and subthemes that emerged in three primary areas: the effects of COVID-19 on mental health, mental health stigma and other social barriers to mental health, and community strengths and strategies for addressing mental health.

Conclusions

COVID-19 surfaced and intensified existing mental health challenges within resettled refugee communities. Community-based mental health interventions should be designed in partnership with the communities they aim to serve. The findings of this study suggest several possible intervention points to support refugee youth and parent mental health, including culturally sensitive group and individual therapy in a trusted community setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) pandemic and the associated lockdown measures had significant mental health effects across all demographics, but some communities experienced a disproportionate increase in mental illness since 2020 [1]. New Americans, particularly resettled refugees, are one such group. Mental illness is prevalent among newly resettled refugee populations at baseline, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic both exposed and contributed to the growing mental health concerns in this population [2, 3].

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, resettled refugees were known to be at an elevated risk for anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychotic disorders, and major depressive disorders in comparison to the general population [4]. Elevated and sustained levels of PTSD and depression often persist for several years after displacement and contribute to post-migration suffering [5]. The process of adapting to a new country can be difficult for refugees due to various stressors and systemic challenges that occur before and after resettlement. The COVID-19 pandemic only intensified these existing vulnerabilities and health-related risk factors for newly resettled refugees. Factors such as employment in high-risk jobs and essential worker status, low levels of education and health literacy, and crowded housing situations made refugees more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 [6,7,8]. The fear of contracting COVID-19, coupled with isolation and uncertainty during the pandemic, only worsened mental health issues. For refugees who have recently resettled, these stressors can compound with existing complex mental health issues and further complicate the resettlement process [9,10,11].

For some resettled refugees, one such stressor may be the potential conflict between parents and children who may “acculturate” at different rates to a Westernized lifestyle, roles, and norms [12, 13]. Refugee youth “often have to navigate two worlds in their everyday lives, one at home and one outside their home” [14]. Many refugee families report noticing changes in their family dynamics after resettlement, including reduced family time and changes in family relationships [15]. Viruell-Fuentes and colleagues note that rather than explaining health disparities through the lens “acculturation,” however, we must acknowledge that structural and policy barriers and experiences of discrimination and racism play an important role in shaping immigrant health outcomes [16]. The experience of fleeing war, civil unrest, economic adversity, persecution, or other stressors can influence the mental health of young refugees and their families. For example, parental PTSD [17] might disrupt important adaptive systems for children, such as family support and secure parent–child attachments, while children with positive social and family environments tend to be more resilient to the challenges of the migration process [18]. War trauma can transform parents’ behavior toward their children, which can create conflict within child and parent relationships [19]. Additionally, isolation is one of the four core stressors identified for refugees going through the resettlement process [20], and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this pivotal stressor.

For these reasons, refugees of all ages require special attention and support regarding mental health. Unfortunately, barriers related to mental health stigma, different conceptions of mental illness, and anxiety regarding interventions for mental illness prevent significant progress.

Refugees have diverse experiences shaped by their culture, country of origin, and the journey that takes them from their home to a second country and ultimately to their resettlement destination, as the structural barriers and discriminatory or racist policies they encounter after resettlement. Consequently, they are a dynamic group without a one-size-fits-all solution for mental health concerns. Previous research from this research group found differences in vaccine acceptability between refugee ethnicities [21], echoing similar research in the field of refugee mental health care, which also found that opinions on mental health vary by different cultural groups [22]. Alemi et al. [23] discuss frameworks that shine a light on the importance of asking refugees for their views regarding the cause of their distress, intending to identify how individuals might resolve the distress through resiliency assets like family support and increasing social capital toward cultural integration [23]. Understanding what the community sees as a fitting intervention for mental health is important.

How mental health disorders are conceptualized and diagnosed is also a challenge in refugee populations. The primary reference used to diagnose mental disorders in the United States is through the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The DSM-5 focuses on symptomatology, emotions, and cognitions that deviate from social norms and cause significant distress or impairment in functioning [24]. Despite the robust nature of the tool in many settings, implementing the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria in refugee populations presents several challenges. Mental health may be conceptualized differently across cultures in ways that do not align with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria [22]. Mental health distress may be expressed through somatic symptoms or viewed through a spiritual or religious lens, rendering Westernized biomedical explanations inaccurate [22, 25]. Language barriers are also a challenge as central concepts to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria may be lost in translation. Concepts of trauma differ across cultures, and stigma around mental health inhibits many refugee individuals from speaking openly about their experiences [22, 26, 27]. There is a growing recognition of the importance of the need for culturally sensitive diagnostic practices, which was supported through the development of the Cultural Formulation Interview in the DSM-5 [28]. The Cultural Formation Interview is designed to help healthcare professionals assess the cultural context of an individual's experience with mental illness. However, there is much to be done to provide culturally informed mental health care that both respects and integrates the diverse backgrounds of refugee populations [28].

Given these considerations, the present study was designed to explore refugee parents’ and young adults' perceptions of, barriers to, and intervention strategies to support the mental health of resettled refugee young people (ages 10–24) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of our study is to understand the beliefs and perceptions held by refugee parents that affect their children’s utilization of mental health resources and what interventions might increase recognition and support for refugee mental health needs, although we did not seek to explore differences between refugee communities. The need for this study arose when local physicians who treat resettled refugees in Syracuse, NY observed a growing mental health crisis among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing obstacles to accessing and utilizing mental health care services has been a crucial concern for the refugee population, happening simultaneously with the increasing evidence that reveals how the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and worsened a worldwide mental health emergency [3]. This study was reviewed and granted exemption by the SUNY Upstate Medical University institutional review board in accordance with United States 45 CFR 46.

2 Methods

Research team: The research team was composed of faculty with appointments in internal medicine and pediatrics (AS), bioethics and humanities (RF), public health (CC), psychiatry (RS), and anthropology (RR). The team also included pre-health student study team members in healthcare-related academic programs hailing from the refugee and immigrant communities of interest in the study (Syrian, Nepali, South Sudanese, and Somali).

Location and Context: Syracuse, New York, a city located in Central New York state, is a sanctuary city that has welcomed more than 10,000 refugees over the past 10 years [29]. Thirteen (13.0%) percent of the population are foreign-born [30]. Although Syracuse hosts refugees from over 25 countries around the world, this study focused on refugees hailing from Syria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Nepal/Bhutan. The majority of refugees in Syracuse resettled in the city after fleeing war, violence, and persecution in their home countries [31].

Community-clinic partnership: This research builds on the foundation of an ongoing collaboration between an academic medical center (SUNY Upstate Medical University) and Catholic Charities of Onondaga County Refugee Resettlement Services Northside CYO (CYO) located in Syracuse, NY. The Community-Clinic Partnership (CCP) was established in 2020 during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The partnership was initially formed to provide critical public health outreach to refugees during the pandemic, including access to COVID-19 testing, clinical care, and vaccination programs held at the local refugee resettlement center (CYO). CYO is one of several refugee resettlement agencies in Syracuse, NY. For decades, CYO has provided a robust support structure for newly resettled refugees, including support services, cultural exchange, and relationship building. Support services include language and citizenship classes, employment assistance, and housing support, facilitated through case managers and refugee peer navigators. The refugee peer navigators are employed by CYO and are resettled refugees themselves. They provide culturally sensitive support and language assistance for new arrivals, extending beyond traditional case management services. Their position in the community as health navigators and former refugees helps to build trust and rapport. The contributions of refugee health navigators improve refugees’ health care access through reliable health information, leading to improved health knowledge and self-sufficiency [26, 27, 32, 33]. Today, the community-clinic partnership supports refugee community health through various community-based projects such as preventive screenings, health literacy sessions, vaccine clinics, and health fairs, as well as research. The interdisciplinary partnership team consists of clinicians, nurses, public health and ethics researchers, refugee peer navigators, case managers, community leaders, and refugee resettlement program directors.

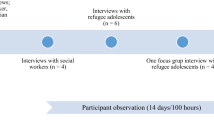

Study design and data collection: The methodological orientation used in this study was interpretive phenomenology and a form of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Using a CBPR approach and interpretive phenomenology lens, we aimed to explore perceptions of the mental health of young people among resettled refugee communities in Syracuse, NY. Interpretative phenomenological analysis is a method that focuses on exploring an individual's personal experience, rather than relying on preconceived theoretical notions. Community-based participatory research, on the other hand, involves collaborating with community members as equal partners throughout the research process, which makes it a crucial methodology when studying vulnerable populations. Previous studies have shown that merging interpretive phenomenology and CBPR can “provide an in-depth view of a community's experiences” and has been used to discover culturally sensitive research practices that reduce health disparities [34].

The reflexivity and insights of study team members who share a linguistic and/or cultural background with the participants is crucial. Team members use their own experiences in the community to conceptualize the phenomenon under investigation. The active involvement of pre-health student study team members who are members of refugee and immigrant communities anchored our choice to pursue a CBPR methodology. The research questions, methods, and data collection tools were designed in partnership with members of the communities, CYO leadership, including the Director of Refugee Resettlement Services, and the pre-health student team members from refugee and immigrant communities that were the focus of the study (Syrian, Nepali, South Sudanese, and Somali) or which were language-concordant with participants (Yemeni). Data collection was performed by the pre-health student team members from those same communities who were integral members of the study team, and all data analysis was member-checked with both the pre-health student team members and with refugee community leaders.

Participant selection: Refugee community members who are young adults aged 18–24 years and parents of young people (those with children ages 10–24) who arrived in the United States as refugees were selected through convenience sampling by study team members. All individuals were required to have at least two years of residence in the United States to participate. Study team members were assisted in recruitment by refugee peer navigators employed by the local resettlement agency. Participants were recruited from the following countries of origin: Somalia, South Sudan (Dinka), Nepal/Bhutan, and Syria. Participant demographics are reported in Table 1.

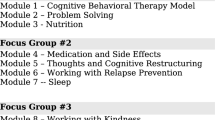

Focus group administration: One parental focus group was held for women and men from each country of origin, and similar gender- and country of origin-concordant focus groups were held for young adults. An interview leader, recorder, and faculty member from the study team were present for each focus group. Eight parental focus groups were led by a pre-health student study team member with language and/or cultural alignment to the parents’ country of origin. Parent focus groups were held in the language of origin for the group. Each gender- and country of origin-concordant parental focus group included eight participants. Parental focus groups included insight from participants hailing from Somalia, South Sudan, Nepal, and Syria. Four gender- and country of origin-concordant focus groups with young adults were held. Young adult focus groups were led by a study team member in English with Syrian and Somali groups and included eight men and women from Syria and nine women and five men from Somalia. All focus groups were held at the local refugee resettlement agency (CYO) in private classrooms. CYO was chosen as a location to administer the focus groups because it is familiar to many refugees as it is used for both case management, support and is centrally located to many refugee communities in Syracuse, NY. Previous research from study team members found that conducting research and facilitating public health outreach activities at CYO has been an effective strategy due to its familiarity, trust, and rapport within the refugee community [21, 35]. Study team members felt that the administration of focus groups at CYO would provide comfort to participants given the sensitive nature of discussing mental health. Verbal informed Consent was obtained from all participants prior to recording.

Data analysis: Transcripts from each set of focus groups (parents, young adults) were coded by three coders. One of the study co-investigators, RF, coded both sets of transcripts and supervised the two teams of two learner team members who coded the parent (JC and AG) and young adult (NA and EO) transcripts. All transcripts were imported into NVivo for Mac to facilitate analysis [36]. For each set of transcripts, all three coders independently coded the first three transcripts and developed coding schemes using an iterative emergent thematic coding approach, and through weekly meetings and discussion, all coding schemes were reconciled by consensus agreement of the coding team and consolidated into one shared codebook. The learners then coded the remaining transcripts in their sets independently, meeting regularly to resolve disagreements and reconcile additions and edits to the codebook. When new codes were added, coders reviewed the earlier transcripts to determine if the new code should be retroactively applied.

All theme and subtheme codes were then organized and consolidated into a set of four major themes relating to the mental health of young refugees, each of which encompassed child codes. Identified top-level themes and their subthemes were returned to the community by the study team through a meeting with a local refugee organization to validate that the themes developed by the coders resonated with their lived experiences.

3 Findings

The findings presented here represent a subset of the body of findings generated by this multipronged study. We focus on three major theme categories that emerged in both the parent and young adult focus groups: (1) the effects of COVID-19 on mental health for resettled refugee young people, (2) the cultural differences that emerged with regard to mental health stigma, and (3) the particular strengths and possible interventions identified by participants in both the parent and young adult groups. Key subthemes are italicized throughout for emphasis. As our data will demonstrate, some findings varied among the different refugee communities, age groups, and gender groups, while other themes were consistent across groups. This variation speaks to the richness and diversity of the resettled refugee experience as well as the strength of some major themes.

Effects of COVID-19 on mental health: Two major subthemes related to the effect of COVID-19 on the mental health of young people and their families were identified in the data. These included the relationship between isolation, depression, and anxiety among young people and the positive and negative effects of stay-at-home orders on family relationships and friendships.

Parents and young adults both described the effect of COVID-related isolation on depression and anxiety. One Syrian young adult observed that “depression way increased after COVID because you barely even see your close friends, just because his family or your family have COVID. So for safety, you have to stay home like no matter what … so, depression went way up” (Syrian Young Men). Similarly, a Nepali parent described the impact of fear of the unknown virus in the early pandemic, observing, “When you go outside, COVID will kill you, and when you stay inside, stress will kill you” (Nepali Father 5). A Somali young adult echoed this sentiment, saying, “My anxiety got really worse. And I think my thoughts started to speak louder than when I’m outside. Usually when I’m outside, I don’t really think much, but being inside a home, just being in your bed all day you start thinking. [You] just think too much” (Somali Young Men).

Another effect of COVID related to the way families responded to having more time together indoors. Parents frequently cited a positive effect of COVID-19 as being the ability to spend more time with their children during stay-at-home orders, while young adults described those same circumstances as reducing their freedom and negatively affecting their mental health. A Dinka father observed that, due to school closures and changes in work schedules, “One good thing that came out of COVID is that lots of parents had more time to spend with their children. A lot of parents were either out of jobs or were working way less hours. So that gave them more time with their children. Them staying home was a good thing but also a challenge” (Dinka Father 1). A Syrian mother described this same phenomenon, saying, “During COVID we spent 3 months at home and we didn’t face any problems, all the time [we were] together we laughed and talked to each other” (Syrian Mother 2). Conversely, a Somali young man described the same scenario as negatively impacting his mental health, observing that “me, I’m a person who likes to communicate with other people. Just be myself. So being inside the house, stuck with siblings and parents just every day the same thing, [it was] just mind-breaking” (Somali Young Men).

Young adults also reported that isolation and mental health problems during COVID affected the quality of their friendships. A Syrian young woman explained how “long distances create emotional damage, just because … you just have this bad energy on you. And I think it affects friendships drastically because, for example, we discussed how mental health impacts a person. So when both people are going through a mental health problem, and then they meet, they’re like, you’re not the friend that I used to hang out with” (Syrian Young Women).

Mental health and stigma: Among both parents of young people and young adults, the theme of stigma surrounding mental health topics was highly prevalent. Young adults frequently discussed how mental health stigma was more prevalent for their parents’ generation, although this differed across refugee groups on the basis of how long each refugee community had been in the United States, with longer-established communities citing more acceptance of mental health topics than more recently arrived refugees. Young adults also described how the intensity of mental health stigma varied by gender, with both men and women agreeing that mental health is a more stigmatizing topic for men than women.

Both parents and young adults across all ethnic groups described how their cultures viewed mental health as a stigmatized topic. In a Dinka parent group, one father said that “to be honest, my personal view on mental health within our community is very stigmatized, like we don't take it seriously. I don't think we believe in mental health, especially the older generation or the ones that have kids here” (Dinka Father). The harms of this stigma were discussed by a Nepali father warning of the consequences of stigmatizing mental illness: ‘“My son is damaged. My son has become mentally ill. Others might talk about him. I won’t share it with others.’ If we think this way then things will get worse” (Nepali Father).

The word “crazy” was often used in connection with this concept. A Dinka mother observed that “when you tell someone that you are going to therapy, now you are being labeled as a crazy person, if you seek help you are labeled someone who is unstable, if you’re on medications then you become crazy” (Dinka Mother). Similarly, a Syrian mother recalled her own experience of being told to seek mental health care, saying, “When they told me to go to a psychiatrist, I told them I am not crazy, I don’t need it. They told me no you are not but sometimes you need to talk to someone other than your husband or friends. I went once and I don’t want to go again” (Syrian Mother).

Like the parents, young adults held similar views about stigma and their communities’ perceptions of mental health and mental illness. A Somali young woman described her community’s view of mental illness:

There is this level of shamefulness … We know every house is struggling with it. It’s, “Don't talk about it, it’s taboo. Don't whisper it, don't seek help. And if you do, don't tell others you are seeking help. We are gonna look crazy.” Because of a lot of shamefulness and trying to look good for other people. (Somali Young Women)

A Syrian young woman echoed this sentiment, saying, “In our community it’s like, when somebody is struggling with a mental problem … in our country it doesn't exist, mental health doesn't exist … They don't know that it's like a real medical problem (Syrian Young Women). The belief that the young adult participants’ peers and community members felt that mental health is either a taboo topic or not “real” was pervasive across ethnic groups and gender groups. Young adults also used the word “crazy” in association with mental illness, although with less frequency than the parents. A Syrian young man noted that he would not recommend therapy to a friend, because “even if you recommend it, you don't know the reaction. ‘Do you think I'm crazy, why should I go to therapy?’ Yeah, some people take it personally” (Syrian Young Men).

Although young adults acknowledged that they felt the stigma of discussing mental health, many noted that their parents were more affected by that stigma. Discussing mental health stigma, one Syrian young woman observed that “that's how we were raised. Like, man like it’s not it’s not such a big deal. But then, as you look more into [therapy], like it actually helps a person but you are Syrian so that is like disobeying” (Syrian Young Women). The idea that seeking therapy as a Syrian is “like disobeying” can be compared to a Somali young man’s discussion of his parents’ own mental health. He notes that his parents “never had to learn how to cope, they've always just pushed everything to the side … And that's why right now we can't express ourselves, because that's how they grew up. They're 40 something years old … and they've never expressed themselves” (Somali Young Men). Both of these young adults attributed mental health stigma to their parents’ generation and their own upbringing. Of note, refugee young adults from Syria, who overall had spent less time in the U.S., described the stigma surrounding mental health more frequently than the young adults from Somalia, who had generally spent more time in the U.S.

Community strengths and strategies: Parents and young adults discussed strengths of their communities that lent themselves to several possible interventions that they felt could improve the mental health of resettled refugee young people and their families. Young adults were more likely to emphasize the importance of personal friendships for improving and maintaining mental health, while parents were more likely to discuss the role of community support and the importance of family relationships. Respondents in both groups also discussed the role of religion in managing mental health challenges. Both parents and young adults frequently discussed their views about individual and group counseling and suggested that both could be helpful for improving the mental health of young people, although there were disagreements about the best modalities and providers of therapy for refugee communities.

Among young adults, the idea that strong friendships are central to supporting good mental health was very common. A Somali young woman described how online conversations with friends and strangers helped with her mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, saying:

I was in certain groups, I was in Zoom calls, I was on FaceTime with people that I've never met just through online and like, supportive groups and really connected to share what's going on in our lives … So just talking to strangers, talking to your friends really helped with that. (Somali Young Women)

A Syrian young woman also described the power of friendship for promoting mental health, explaining how she would support a friend who was struggling:

First, you have to take them out of this house … maybe just go to Starbucks, you know, talk about it, that might help people a lot. To show them that there's a purpose to life, there's happiness, it's not just like, you're gonna grow out of it. (Syrian Young Women)

Other young adult participants also described how conversations with friends can promote mental health as well, although this view was less common among the parent participants.

Some parents did emphasize the value of community support, however, including a Somali father who described how he could rely on his friends and community for strength, saying, “The community is built the right way and we help each other. If I need anything … I can get help with it. We put our strengths in our community” (Somali Father). Other parent respondents refuted this view, suggesting that their community was not sufficiently cohesive. Several mothers from the Dinka group suggested that a stronger community, or even a community center, would be helpful for supporting mental health: “If we had a place where people can go to gather and work together and know each other perhaps we can learn from each other what are the best ways to raise children and therefore those can also be sources of emotional wellness” (Dinka Mother).

While young adults were quick to emphasize the value of relying on friends for support, parents were more likely to discuss the value of parental and family support for improving the mental health of young people. A Syrian mother described the importance of “talking to the child and giving him the feeling that the safest place to get help is his parents, not from the outsiders. We are his friends, and his sister is not his enemy” (Syrian Mother). This emphasis on seeking support from family rather than “outsiders” relates to the theme below about treatment modalities. A Somali father also expressed the importance of providing support within the family, recommending that “when they’re young you start with the deen [teachings] of Islam and having them open to you and tell them their problems and everything else” (Somali Men). This relates to the next point theme, the role of religion in supporting (or harming) mental health.

Many refugee young people discussed the importance of religion in their lives and the ways it was or was not beneficial to their mental health. One Syrian young woman described how reading the Quran and reflecting on her religion helped her manage her anxiety around school, saying, “When I have something that I'm worried about a lot, like for example a final exam … I would start studying for it and every day more anxiety goes to the test. When I hear some Quran or read some Quran, it’s going to be a lot of help for me, like it just slows me down” (Syrian Young Woman).

Parents also described the importance of religion and that religion is the best response and is preferable to seeking treatment for mental illness. One Syrian father observed:

In Islam, if you have faith … then you would completely understand that whatever happens in your life is written for, and it is in God’s hand… So when it comes to going to psychiatry, for me personally and what I believe: if the person is accepting himself and there is inner self-satisfaction, and [he is] satisfied with God’s plan and judgment, that person would not reach a point that requires going to a psychiatrist. (Syrian Father)

A Somali father echoed this sentiment, noting that “when we first encounter a problem with a child first … we would put the Quran on him … [If] the sickness goes on and then that’s when you go to the community or the doctor. And if you go through all of that and nothing is being fixed, you can go back to the Quran” (Somali Father). This view that religion should be the first response to mental illness was shared by some Nepali respondents as well.

Of course, some young people did not agree with their parents that religion is the best response. One Somali young woman described with frustration a conversation she had with her mother about her traumatic experiences as a refugee:

[Mental illness] doesn’t exist. Like their issue is normalized. We move on, we go back to Allah and ask for forgiveness, ask for guidance. And that’s basically their therapy, of how they move on. (Somali Young Woman)

Other young people similarly spoke about the difficulties they experienced when their families felt religion was the best response to mental health challenges. A Somali young woman described her family’s disapproving reaction to her getting a therapist, saying, “He was like, what is wrong with you? We can do this. We can do that. Like other things, like put the Quran on you” (Somali Young Woman). Similarly, a Somali young man described how his community promotes religion as a cure for mental illness: “What they will push on you is the religion, so they will say ‘[read] the Quran, pray five times a day, you’ll probably get better … Allah will answer your prayers’” (Somali Young Man).

Many of the strategies discussed across all groups centered on the acceptability of individual and group therapy, with young adults expressing more openness to individual therapy, although there was disagreement regarding who should provide the counseling. Both parents and young adults across ethnic groups expressed enthusiasm for mental health support groups. In fact, several groups of parents and young adults cited the research focus groups in which they were participating as a possible model for a therapeutic intervention that could promote mental health for young people and their parents.

Among Nepali parents in particular, there was a strong view that counseling would be beneficial both for children and for their parents. One Nepali father asserted, “We should make counseling available for the children and the parents. Counseling helps and can potentially help children recover” (Nepali Father). The others in the group agreed, although Nepali fathers and mothers both indicated that they would prefer for their families to receive counseling from clinicians outside their own community: “If a Nepali tries to counsel another Nepali then it’s like hitting your leg with your own ax. If somebody else from another community, possibly along with an interpreter, could provide the counseling then it would be much better” (Nepali Mother). A Dinka mother expressed a similar view, saying, “I would rather go to a professional therapist and have them talk to me then go to someone in the community because that situation will be taken as a gossip … I have stuff that I need to talk to someone about and I can’t come to the community” (Dinka Mother).

This view that therapists should be from outside the refugee community was not shared by all respondents. Two Syrian mothers explained:

Syrian Mother 7: [An Arab mental health counselor] would be close to our culture and traditions.

Syrian Mother 1: He would understand us and know our needs.

Similarly, many young adults supported the idea of individual therapy, but felt the therapist should be culturally concordant. A Somali young woman explained the challenges of finding a culturally appropriate therapist, saying:

As a Somalian who's also black, Muslim, and all of us are women as well. So it’s already hard enough finding a therapist as a black person. So imagine having to find somebody who’s a black person who’s also Muslim and a woman. Just that kind of comfortability is one aspect. The other aspect is someone who's just culturally sensitive. Like, I can't just cut off my parents, Cindy, it's not gonna work like that. (Somali Young Women)

Given these divergent views, there was no overall consensus on whether a culturally concordant clinician would be better or worse than one from within the community.

Parents and young adults alike suggested that group therapy sessions would be helpful for supporting the mental health of young people and their parents. A Syrian young woman suggested that she would enjoy group therapy, saying, “I think it’d be more fun to listen to other people you actually empathize with” (Syrian Young Women). Several respondents also suggested that just having a place to discuss mental health, like the space provided by the research focus group, would be beneficial. A Nepali father suggested, “If we could have this kind of session a couple of times in a month or a couple of months, that would help. They will know and maybe understand that many people have these kinds of experiences” (Nepali Father). In fact, at the end of the Syrian Mothers focus group, the participants even requested that we keep holding group meetings to continue the conversation around mental health.

4 Discussion

This study identifies some mental health issues that parents and young adult refugees face, as well as some strengths and potential intervention points. Although participants in the Dinka, Nepali, Syrian, and Somali refugee communities each face unique challenges in resettling and adjusting to life in the United States, they all share many of the same barriers to mental health. This study did not aim to explore the differences between these communities, although sometimes differences did arise and have been noted above. Our focus groups echo and reinforce existing literature about resettled refugees’ views of mental health, but in the context of COVID-related isolation and anxiety, these views were intensified and made more urgent. Given the deep and lasting effects of the pandemic on economic and social well-being around the globe, this finding aligned with our hypotheses.

Despite the identified challenges COVID-19 posed to mental health, parents also discussed positive outcomes from the pandemic. Parents especially cited the benefits of being able to spend more time with their children and families due to the stay-at-home orders. Yet young adult participants viewed the time at home as detrimental to their mental health, and many stated being stuck inside increased their anxiety and diminished their ability to maintain peer friendships. However, some young adults discussed coping mechanisms that they were able to implement to overcome the isolation brought upon by the stay-at-home orders. Many discussed how they were able to connect with friends via Zoom or over the internet, or focused on activities they could participate in outside with friends.

Mental health stigma presents a major cultural barrier to mental health help-seeking among refugees. Past studies have found that negative perceptions of mental health and concerns about social consequences associated with mental illness often prevent individuals from seeking help [37]. In some instances, individuals in refugee communities who do seek care are considered mentally unfit to be around others, and there are concerns that the stigma resulting from obtaining care may be more damaging than receiving no mental health care at all [38]. Our data resonates with this literature, and reinforces previous findings that the discussion of mental health is considered shameful and taboo in some refugee communities and may jeopardize one’s position within their community [22, 37].

We found that that discussion of mental health stigma was highly prevalent among both parents and young adults. Parents and young adults frequently used the word “crazy” when discussing perceptions of mental illness, and participants expressed a general fear that seeking therapy for mental health could result in being labeled as such. Although young adults discussed the stigma surrounding mental health for themselves and their peers, they were also aware of how stigma negatively impacts their parents’ mental health behaviors. Time in the United States appeared to affect acceptance of mental health care-seeking behaviors and lessened stigma in some circumstances; those refugee groups who had spent more time in the United States mentioned mental health stigma less than groups who were more recently resettled or discussed it as being less prevalent in their communities.

Our findings revealed that health literacy barriers can prevent uptake of mental health care in some refugee populations, which also resonates with previous research in this space. Prior studies have shown that many refugees do not always understand the wide scope of mental disorders, a factor that is also limited by low communication and discussion around mental health within some communities due to stigma and fear [39]. Compounding these health literacy barriers faced by refugees are the Westernized diagnostic methods like the DSM-5 that are used to diagnose and treat mental health disorders. Mental health disorders may be conceptualized and expressed differently across cultures in ways that do not align with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, limiting access to care. Stigma furthers this barrier in that many refugee individuals do not speak openly with healthcare providers about their past traumatic experiences.

Another barrier related to health literacy that emerged from our focus groups was uncertainty or misunderstanding regarding private health information. Our findings identified gaps in understanding about confidentiality and the therapeutic relationship between counselor and patient. Many participants were concerned that mental health counselors would share their information within the community, thus preventing them from seeking care from culturally congruent and/or community member mental health support teams. Additional efforts to increase health literacy and a general understanding of health privacy will be important to disseminate to newly resettled populations.

Although some parental focus group members expressed concern about seeking mental health care and therapy modalities from a culturally congruent and/or community member, not all focus group members shared this view. Some focus group members preferred a culturally congruent counselor, while others preferred to seek help outside of their communities. This resonates with previous findings that sharing intimate information with counselors outside of one’s own community can sometimes be considered inappropriate [40, 41]. Trust is an important factor in determining the appropriate counselor for a given individual or group, as some participants may have had traumatic experiences at the hand of governments or other authorities, both before and after resettlement. This may lead to fear and distrust of authorities, which can also affect uptake of mental health care services. Previous research indicates that interventions that leverage community health workers and peer support/peer mentors who share cultural and linguistic backgrounds with the patients they aim to serve are often effective at addressing mental health challenges for resettled refugees [42,43,44].

Despite the lack of agreement regarding the demographics of appropriate mental health providers, both parents and youth felt that group counseling would be a beneficial treatment modality. These findings reinforce the importance of community factors in providing mental health care to resettled refugees [45,46,47,48]. Our research group has previously found an emphasis on using a trusted, local community site to connect with the refugee population [21]. For this study, we hosted our focus groups at one of the local refugee resettlement locations in Syracuse, NY. This site is centrally located within the refugee community and has consistently remained a safe space for refugee groups to come together for support services. It is used for a variety of resettlement services including language classes, youth programs, and job assistance, in addition to the health outreach efforts by the research teams’ community clinic partnership. Several focus groups suggested that mental health discussion groups or counseling could occur at this same site, indicating that the benefit of this type of care can be gained outside of a stigmatized mental health care setting. This finding is corroborated by other studies focusing on increasing uptake of mental health care services in this population [23, 45, 49]. However, some studies suggest that even when community-based mental health treatment is offered, acceptance rates can be low [25, 39]. This low uptake may result from the reality that many resettled refugees have more pressing needs and stressors in their daily lives or other experiences of structural barriers, and therefore engaging in counseling or discussing past trauma may not be a priority [50].

Another reason for low uptake of formal mental health programming may be that, for some resettled refugees, religious support or informal friend or family assistance may be preferable to community-based therapy [22]. The importance of both religion and friendships emerged as important strengths and points of resilience across focus groups. Young adults discussed the importance of maintaining strong friendships in managing mental health challenges. These focus group members discussed the mental health benefits of online modalities like connecting over Zoom with friends during the pandemic, in addition to bringing friends outside and having open discussions when they identified that the friend was struggling. Parents were less likely to discuss coping strategies regarding friendships compared to the youth focus groups, but often emphasized the importance of relying on family support or their communities.

Both parents and young adults discussed the importance of religion in their lives, and how it may be used to cope with mental struggles. Young adults spoke about how their families often felt that religion was the best response to mental challenges, and some cited that religion is promoted as a cure for mental illness. When mental health challenges arise, parents often felt that the answer is not to go to a therapist, but to pray, forgive, and move on. These statements align with prior research findings from Piwowarczyk et al. [41]; Bettmann et al. [51]; and Alemi et al. [23] citing that preferred treatments often involve religious solutions or talking with family or friends [23, 41, 51].

Interestingly, although the study's goals were to explore refugee parent and young adult perceptions of mental health to specifically support young people aged 10–24, we found that conversations in the focus groups were bidirectional about parents and children. Parents came to speak about their children, yet they also spoke about themselves, their culture, and how they would approach therapy and mental health care. In addition, the young people spoke about their own experiences and also often discussed their parents’ mental health. In addition, although we did not seek to address this point, many participants independently surfaced the idea of participating in therapy, either in a group or individually, with mixed feelings with regard to modality and also to the importance of cultural concordance with a therapist.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced and intensified existing mental health challenges within resettled refugee communities. The findings of this study suggest several possible intervention points to support refugee youth and parent mental health, including culturally sensitive group and individual therapy in a trusted community setting. Future community-based participatory research, in partnership with the affected communities, will be necessary to develop interventions that will be responsive to the needs and unique challenges that individual refugee communities face.

5 Strengths, limitations, and conclusions

Strengths: As is typical of qualitative research, our findings are not meant to be generalizable beyond the context in which they were generated. Instead, through the application of multiple methodological validity and reliability checks, we have generated research that is instead transferable into other contexts by understanding and acknowledging the respondent and researcher biases that shaped them.

We worked to promote the validity of our findings by leveraging the longstanding community-clinic partnership led by the senior member of our research team, through which we have developed relationships with multiple resettled refugee communities in Syracuse, NY grounded in trust and mutual respect. By incorporating the perspectives and experiences of refugee community leaders and young adult members of these communities into our research design, data collection, and member-checking of our findings, we have confidence in the validity of the findings presented here. Additionally, this paper has the benefit of building on a strong evidence base regarding the views and experiences of mental health among resettled refugees in the United States. Triangulating our findings with both this evidence base and the experiences of our community and clinical team members additionally lends confidence to the validity of these findings. Reliability was promoted by the consistent application of rigorous qualitative research methods, including analytic and personal memo-writing, constant intercoder discussion and comparison, and coding audits.

Limitations: As noted above, these findings cannot be generalized beyond the context in which they were generated, which is a feature of much qualitative work. Even so, there are several factors that could limit the validity of our findings. Despite efforts, we were unable to recruit young adults from the Dinka and Nepali communities. This was due in some cases to timing, as many young adults were away for school when we attempted recruitment. In other cases, the mental health stigma that we describe above led some Dinka community members to refuse participation due to concerns about confidentiality and fears that young adult peers might judge their participation in focus groups as an indication that participants were mentally ill. This meant that although members of four refugee communities were represented in the parent data, only two communities contributed to our young adult data. Despite this limitation, however, we believe the rich data we gathered across the groups who did participate remains important and relevant in itself. Another limitation of this data is that although focus groups often reveal insights grounded in social dynamics and agreement/disagreement, these dynamics are largely absent from our report. This is because the parent focus groups were conducted in the participants’ preferred languages and then translated into English, so some of the nuance of social dynamics may have been lost in the translation process. We are therefore cautious about reporting social dynamics and instances of agreement or disagreement.

Conclusions: Although the COVID-19 pandemic no longer dominates the lived experiences of resettled refugees in our communities, its impact will be felt for years to come. Taken together, our findings lay the groundwork for future studies that could implement and evaluate the acceptability of community-based mental health programming drawing on the preferences and strengths identified by our focus group participants. And while this particular pandemic may have run its course, future social shocks are inevitable. It is imperative that public health and mental health professionals work in concert with the communities they aim to serve, including refugee communities, to create systems that will support the mental health of all.

Data availability

The deidentified datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(7):1151–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00787-021-01856-W.

Brickhill-Atkinson M, Hauck FR. Impact of COVID-19 on resettled refugees. Prim Care. 2021;48(1):57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POP.2020.10.001.

Osborn TL, Wasanga CM, Ndetei DM. Transforming mental health for all. BMJ. 2022;377: o1593. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1593.

Ermansons G, Kienzler H, Asif Z, Schofield P. Refugee mental health and the role of place in the Global North countries: a scoping review. Health Place. 2023;79: 102964. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HEALTHPLACE.2023.102964.

Blackmore R, Boyle JA, Fazel M, et al. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020;17(9): e1003337. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1003337.

Endale T, Jean NS, Birman D. COVID-19 and refugee and immigrant youth: a community-based mental health perspective. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S225–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/TRA0000875.

Kurt G, Ilkkursun Z, Javanbakht A, Uygun E, Karaoglan-Kahilogullari A, Acarturk C. The psychological impacts of COVID-19 related stressors on Syrian refugees in Turkey: the role of resource loss, discrimination, and social support. Int J Intercult Relat. 2021;85:130–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINTREL.2021.09.009.

Perreira KM, Yoshikawa H, Oberlander J. A new threat to immigrants’ health—the public-charge rule. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):901–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1808020.

Jorgenson KC, Nilsson JE. The relationship among trauma, acculturation, and mental health symptoms in somali refugees. Couns Psychol. 2021;49(2):196–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020968548.

Rumbaut RG. Paradoxes (and orthodoxies) of assimilation. Sociol Perspect. 1997;40(3):483–511. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389453.

Schweitzer R, Melville F, Steel Z, Lacherez P. Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled sudanese refugees. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(2):179–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x.

Sluzki CE. Migration and family conflict. Fam Process. 1979;18(4):379–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1545-5300.1979.00379.X.

Harris KM, Chen P. The acculturation gap of parent-child relationships in immigrant families: a national study. Family Relat. 2022;72(4):1748–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12760.

Meyer C, Alhaddad L, Stammel N, et al. With a little help from my friends? Acculturation and mental health in Arabic-speaking refugee youth living with their families. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1130199. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2023.1130199/BIBTEX.

Weine S. Family roles in refugee youth resettlement from a prevention perspective. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(3):515. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHC.2008.02.006.

Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099–106.

Back Nielsen M, Carlsson J, Køster Rimvall M, Petersen JH, Norredam M. Risk of childhood psychiatric disorders in children of refugee parents with post-traumatic stress disorder: a nationwide, register-based, cohort study. Lancet Pub Health. 2019;4(7):e353–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30077-5.

Davis C, Wanninger A. Mental health and psychosocial support considerations for Syrian refugees in Turkey: sources of distress, coping mechanisms, & access to support. Int Medical Corps. 2017;26:2019.

Rizkalla N, Mallat NK, Arafa R, Adi S, Soudi L, Segal SP. “Children are not children anymore; they are a lost generation”: adverse physical and mental health consequences on Syrian refugee children. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2020;17(22):1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17228378.

Davis SH, Winer JP, Gillespie SC, Mulder LA. The refugee and immigrant core stressors toolkit (RICST): understanding the multifaceted needs of refugee and immigrant youth and families through a four core stressors framework. J Tech Behav Sci. 2021;6(4):620–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/S41347-021-00218-2.

Kuroda M, Shaw AV, Campagna CD. The experiences of community health workers when communicating with refugees about COVID-19 vaccines in Syracuse, NY: a qualitative study. Heliyon. 2024;10(4): e26136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26136.

Moses S, Holmes D. What mental illness means in different cultures: perceptions of mental health among refugees from various countries of origin. Ment Health Glob Chall J. 2022. https://doi.org/10.56508/mhgcj.v5i2.126.

Alemi Q, James S, Montgomery S. Contextualizing Afghan refugee views of depression through narratives of trauma, resettlement stress, and coping. Transcult Psychiatry. 2016;53(5):630–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461516660937.

DSM-5. Cleveland Clinic. 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/24291-diagnostic-and-statistical-manual-dsm-5. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

Savin D, Seymour DJ, Littleford LN, Bettridge J, Giese A. Findings from mental health screening of newly arrived refugees in Colorado. Pub Health Rep. 2005;120(3):224–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490512000303.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Guidance for Community Health Workers. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/php/community-health-worker-resources/. Accessed 17 July 2024.

Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x.

Cultural Concepts in DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. 2013. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM_Cultural-Concepts-in-DSM-5.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

Scott M. Resources continue to expand for growing Syracuse refugee population. CNY Central. 2024. https://cnycentral.com/news/local/resources-continue-to-expand-for-syracuse-refugee-population. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

QuickFacts: Syracuse city, New York. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/syracusecitynewyork/RHI125218#RHI125218. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

Allen P, Breidenbach M. Refugees in Onondaga country: where are they from? When did they arrive? Syracuse.com. 2023. https://www.syracuse.com/news/2017/02/refugees_in_onondaga_county_where_are_they_from_when_did_they_arrive_1.html. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

American Public Health Association. Community Health Workers. 2024. https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers. Accessed 17 July 2024.

Harris MA, Lupone CM, Asiago-Reddy E, et al. Community-clinical partnership: engaging health navigators to support refugees and non-refugee immigrants amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Sq. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-115115/v1.

Bush EJ, Singh RL, Kooienga S. Lived experiences of a community: merging interpretive phenomenology and community-based participatory research. Int J Qual Methods. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919875891.

Shaw J, Anderson KB, Fabi RE, et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention and behavior in a large, diverse U.S. refugee population. Vaccine. 2022;40:1231–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.057.

QSR International Pty Ltd. 2023.

Kim W, Yalim AC, Kim I. “Mental health is for crazy people”: perceptions and barriers to mental health service use among refugees from Burma. Commun Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):965–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00700-w.

Ellis BH, Miller AB, Baldwin H, Abdi S. New directions in refugee youth mental health services: overcoming barriers to engagement. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2021;4(1):69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2011.545047.

Karamehic-Muratovic A, Sichling F, Doherty C. Perceptions of parents’ mental health and perceived stigma by refugee youth in the U.S. context. Commun Ment Health J. 2022;58(8):1457–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00958-2.

Brown F. Counseling Vietnamese refugees: the new challenge. Int J Adv Couns. 1987;10(4):259–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00121521.

Piwowarczyk L, Bishop H, Yusuf A, Mudymba F, Raj A. Congolese and Somali beliefs about mental health services. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(3):209–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000087.

Peterson C, Poudel-Tandukar K, Sanger K, Jacelon CS. Improving mental health in refugee populations: a review of intervention studies conducted in the United States. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41(4):271.

Nazzal KH, Forghany M, Geevarughese MC, Mahmoodi V, Wong J. An innovative community-oriented approach to prevention and early intervention with refugees in the United States. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(4):477. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037964.

Barbaresos F, Georgiou N, Vasilopoulos F, Papathanasiou C. Peer support groups and peer mentoring in refugee adolescents and young adults: a literature review. Glob J Commun Psychol Pract. 2023;14(2):1–18.

Miller KE. Rethinking a familiar model: psychotherapy and the mental health of refugees. J Contemp Psychother. 1999;29(4):283–306. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022926721458.

Watters C. Emerging paradigms in the mental health care of refugees. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1709–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00284-7.

Weine SM. Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam Process. 2011;50(3):410. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1545-5300.2011.01366.X.

Strang A, Ager A. Refugee integration: emerging trends and remaining agendas. J Refug Stud. 2010;23(4):589–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq046.

Mitschke DB, Praetorius RT, Kelly DR, Small E, Kim YK. Listening to refugees: how traditional mental health interventions may miss the mark. Int Soc Work. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816648256.

Wong EC, Marshall GN, Schell TL, et al. Barriers to mental health care utilization for U.S. Cambodian refugees. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1116–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1116.

Bettmann JE, Penney D, Clarkson Freeman P, Lecy N. Somali Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Illness. Soc Work Health Care. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2015.104657.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people and organizations for their support of this work: Sophie Pollack-Milgate, Joanna Berg, Alexandra Rodriguez, Athyang Aman, Nishal Basnet, Dahabo Farah, Hawa Omar, Aakritee Sharma, Bernard Appiah, Sandra D. Lane, Felicia Castricone, Razan Shalash, Jay Subedi, Ali Adan, Hassina Adams, Jan-Juba Arway, Jasenko Mondom, Tai Shaw, Beatrice Faida, Chol Majok, Razan Shalash, Jok Jok, Liban Mohamed, the Syracuse New Americans Forum, and the Clark Endowment for Pediatric Research through Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital and the Upstate Foundation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clark Endowment for Pediatric Research through Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital and the Upstate Foundation supporting research relevant to child health, 2020–2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF and CC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RF led the qualitative data analysis, assisted by NA and EO. AS acquired funding and helped conceptualize the research project. RF, RS, and CC helped conceptualize the research project and supervised data collection. RR helped conceptualize the research project. NA, EO, NA, WA, and SA helped conceptualize the project and assisted with data collection. All authors reviewed and provided critical feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and granted exemption by the SUNY Upstate Medical University institutional review board in accordance with United States 45 CFR 46 (IRB reference number 1768846). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as established by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabi, R., Campagna, C.D., Aljabarrin, N. et al. Resettled refugee parent and young adult perspectives on mental health after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Discov Ment Health 5, 53 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-025-00182-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-025-00182-w