Abstract

Shared values play an important role in attracting new tourists, retaining existing ones and gaining an important competitive advantage. Building upon the Commitment-Trust model, this study tested the role of shared ecological values in the creation of tourist trust and relationship commitment, and finally tourist behavioral intention. To test the hypotheses, a sample consisting of 480 mountaineering tourists of two representative travel agencies were surveyed, and a mixed-method approach based on a quantitative survey (n = 436) and qualitative interviews (n = 60) was also adopted to examine their relationships. Results revealed that shared ecological values between tourists and travel agencies were significantly negative predictors of credibility, while credibility and benevolence emerged as significantly positive predictors of relationship commitment. Moreover, credibility and relationship commitment were partially positively predictors of tourist’s behavioral intentions. The findings enrich the extant knowledge on mountaineering tourist relationship marketing and human-nature relationships and provide implications for destination management and wildlife protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The past five years have witnessed a rapid development of mountaineering tourism in China1. According to Zhong et al., Chinese outdoor sports market scale reached 74.8 billion yuan, of which the skiing, mountaineering and camping market accounted for 18.5%, 14.5% and 20.8% in 2022, respectively2. As for mountaineering tourism, the core market size for climbing in China in 2022 was 10.7 billion yuan, with a year-on-year growth of 6.5%. In fact, 197 million Chinese adults, have taken an adventure trip, of which 68 million participated in ‘hard adventure activities’ including Mountaineering tourism3. The value of the Mountaineering tourism industry has been estimated at “half of the size of the tourism industry as a whole,” approximately $15 billion dollars (including equipment sales)4.

Mountaineering tourism is a popular activity that involves traversing challenging terrain and heights, often in remote and pristine locations. On the one hand, this tourism behavior may have a significant impact on the environment, with mountaineers potentially causing damage to fragile ecosystems and indigenous cultures. Thus, environmental protection is essential for the development of mountaineering tourism.

On the other hand, it is evident that today’s customer is more concerned about the environment than ever before5. Especially Since August 24th, Tokyo Electric Power Company announced to start discharging treated radioactive wastewater from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean, global consumers expressed seriously concern about seafood safety. Fukushima’s badly hit fisheries, tourism and economy are still recovering from the disaster. There is indication that today’s customers are demanding quality products and services from companies that hold higher environmental and ecological values6. A company that shares the customer’s environmental and ecological concerns has the potential to gain a competitive advantage over its competitors, as these shared values significantly contribute to the development of customer trust and relationship commitment with the company.

From a theoretical point of view, shared value has been extensively studied within organizational and HRM domain in the past, while neglecting its application in relationship marketing between business and customers, which is considered as huge potential in theory and management practice. Furthermore, a thorough review of previous value-attitude-behavior literature indicated that no study has investigated the roles shared ecological values have affected mountaineering tourists’ behavioral intentions, which provides a new perspective for our research. In addition, relationship marketing holds particularly importance in the travel and tourism industry, building customer trust is one of the most crucial factors in developing a relationship between a customer and a provider7. An increasing number of researchers have recognized its importance in relational marketing and have incorporated it into buyer-supplier relationship. Within this domain, a thorough review of previous literature indicated that no study has investigated the role trust (reflected by credibility and benevolence) has affected mountaineering tourists’ behavioral intentions, this provides a new theoretical research perspective for this research.

From the perspective of the tourism industry development, research suggests that tourists are calling for higher quality services from organizations that prioritize environmental and social values8. As the travel industry expands, expectations for its performance in both socially and environmentally – were heighten. Tourism agencies that share these ecological values with their tourists stand to benefit from their beliefs. A study of tourists that participate most frequently in Mountaineering tourism indicates that they have higher than average incomes and levels of education, are willing to spend more than the average tourist, and possess environmental ethics9. Over the past three years, the tourism sector has experienced a precipitous drop in revenue due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to succeed in today’s marketplace, it is necessary to gain a competitive advantage through developing long-term relationships with these most valuable tourists10.

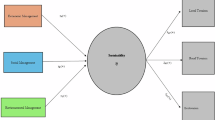

This study hypothesized that shared ecological values were a significant precursor of buyer-supplier relationship development. Also, the outcomes of relationship development were investigated. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the role of shared ecological values, trust, and relationship commitment in developing relationships between mountaineering tourism providers and their tourists. Specifically, the role of shared ecological values between Mountaineering tourists and travel agency in the establishment of tourist trust (reflected by credibility and benevolence) and relationship commitment was investigated, besides the relationships among tourist trust, relationship commitment and long-term behavioral intentions (i.e., cooperation, positive word-of-mouth, repurchasing intentions, and reluctance to change) was also studied (see Fig. 1).

Previous researchers have also done a lot of quantitative researches for examining factors influencing tourists’ supplier-buyer relationship in western countries; however, few have done for identifying factors and their relationships under Chinese mountaineering tourism context. An understanding of these concepts and how they can assist providers in gaining a more high-end, committed clientele could help them achieve the competitive advantage they desire.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Shared ecological values and trust

In 1996, Fulton et al. proposed an instrument for measuring fundamental issues related to human-wildlife interactions, and they established two dimensions of wildlife value orientation in humans, “use” and “protection” dimension11. They then examined the relationship between wildlife value orientations and participation in fishing, hunting, and wildlife observation. In collaboration with wildlife managers and planners, they identified eight categories of wildlife value orientations that are important for wildlife planning (Table 1).

Similar Research conducted in different countries, such as the Netherlands12,13,14, Germany15, the USA16,17, Greece18, Denmark19, and China20, have proved the reliability of wildlife value orientations scales under different cultural background. Therefore, in this study, we adapted wildlife value orientations to wildlife ecological orientations so as to better suit the background of mountaineering tourism.

While researchers studying interpersonal trust acknowledge it as a multidimensional construct, trust in marketing has traditionally been viewed as unidimensional. Moorman et al. define trust as “a readiness to rely on a dealing partner in whom one has confidence”21. Doney and Cannon argue that trust comprises two distinct elements: credibility, the customer’s belief in the provider’s expertise and reliability in performing the job effectively, and benevolence, the customer’s belief that the provider will act in their best interest, prioritizing the customer’s needs22. Reliability and working in the partner’s best interest are central to all trust definitions. In tourism, benevolence refers to the belief that tourism provider is motivated by a genuine concern to place tourists ‘interests ahead of his or her manifest profit motive23. A study conducted by Nguyen suggested that benevolence has a positive impact on satisfaction as well as customer-company relations24. Indeed, an abundance of contemporary research underscores the significance of benevolence exhibited by tourism suppliers in enhancing tourist satisfaction25.

Morgan and Hunt proposed that when cooperation partners hold shared values, they are more likely to be committed to their relationships. Shared values refer to common beliefs about important or unimportant behaviors, goals, and policies26. According to their study on commitment-trust relationships, shared values were the only concept directly preceding both relationship commitment and trust. Shared values contribute to trust and create a tendency to trust27.

Wang et al. found that a customer’s identification with important values related to their preference for providers, and the stronger the consumer’s identification with the common values and images brought by the brand, the more resistant they become to changing that preference28. Shared value systems are believed to ensure sustained interdependence, as relationship investments are sustained through joint investments29. Furthermore, Dunaetz et al. conducted a research to investigated the relationship among shared value, trust and commitment, and the outcome demonstrated that shared value indeed posed positive influence on trust and commitment30. Based on the above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1

Shared values of ecological use, ecological experience, ecological education, ecological existence, and ecological activity are significant and positive predictors of credibility.

H2

Shared values of ecological use, ecological experience, ecological education, ecological existence, and ecological activity are significant and positive predictors of benevolence.

Shared Ecological values and buyer-supplier relationship commitment

The trust-commitment model offers a valuable foundation for this article, as it emphasized the significance of “shared values”, and regarded it as the sole precursor to both trust and commitment31. Further empirical researches across different settings have validated that shared values constitute a crucial element in a relationship marketing strategy. In 2005, Sin et al. have investigated B2B marketing in China, and they found that shared values are an integral component of relationship marketing approach32. Kashyap and Sivadas examined the impact of shared values in the dynamics of channel partner relationships. They concluded that shared values not only inspire partners to fulfill their contractual obligations but also to exceed them, exhibiting behaviors that enhance the mutual trust33. Another study of relationship marketing within the commercial banking industry, Yoganathan et al. affirmed that shared values are instrumental in fostering a relationship marketing approach and to enhance mutual trust and commitment34. Thus, we can propose the following sub-hypothesis: Shared values of ecological use, ecological experience, ecological education, ecological existence, and ecological activity are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s commitment to their relationship with the agency.

In 1994, Morgan and Hunt initiatively proposed the commitment–trust theory, which stated that trust and commitment were important variables in relationship marketing. In their view, Commitment to a relationship is described as “a dealing partner believing that maintaining a persistent relationship with another is so significant as it would lead to maximum benefits for both,” while trust is “a readiness to rely on a dealing partner”. They found that the relationship between trust and relationship commitment was that trust is a preceding state for the development of commitment26. Trust is recognized as a key factor in predicting commitment35,36. Several researches have documented substantial correlations between trust and commitment37,38,39, Given that commitment is inherently linked to making sacrifices, individuals have a propensity to look for business collaborators they deem trustworthy. They only make their commitment once a solid foundation of trust has been established40. Similarly, Sui Pheng suggested that Relationship marketing concentrated on building long-term relationship with stakeholders rather than short-term transactions41. Consequence, Lumineau stated that Distrust leads to misunderstanding, suspicion, and the rise of contradictions between the two sides, and this would decrease relationship commitment between cooperating partners and resulting in short-term exchanges42. Thus, Trust has posed influence on relationship commitment28. Following the principles of the trust-commitment theory, we assert that trust is a predictor of commitment7,26. In line with past studies, trust is an antecedent of commitment26,38,43,44. The Following hypothesis is formulated:

Thus, based on above, we can propose the following hypothesis.

H3

Shared values of ecological use, ecological experience, ecological education, ecological existence, and ecological activity, and credibility and benevolence are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s commitment to their relationship with the agency.

Buyer-supplier relationship and behavioral intention

Although some authors believe that trust and commitment are in and of themselves highly desirable outcomes of any relationship45, there are many possible benefits that can be associated with their development. Four of these relationship outcomes include Collaboration, word of mouth communication, repurchase, and reluctance to change providers.

Collaboration is defined by Moirano et al., as working together to achieve mutual goals46. Anderson and Narus characterized trust as a key factor in fostering Collaboration within business relationships47. Such cooperative efforts are not only proactive but also contribute to the achievements of relationship marketing26. Furthermore, Collaboration is highlighted as a unique result shaped by the combined influences of both trust and commitment26,47,48. In fact, before the trust-commitment model was tested by Morgan and Hunt26, there was a lack of theory explaining the role of Collaboration in relationships. However, in their study, they found that cooperation was a direct outcome of both relationship commitment and trust. This study will measure Collaboration through the concepts of the customer’s willingness to organize groups of people to patronize a provider and by their willingness to give feedback to the provider regarding services provided.

H4

Credibility, benevolence and relationship commitment are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s Collaboration with the agency.

Berger define word-of-mouth communication as “volitional post-purchase communication by consumers”49. When a party or buyer places their trust in a company, that trust engenders a sense of commitment and leads to the sharing of favorable word-of-mouth regarding the business partner. High levels of trust and commitment can significantly increase the likelihood of positive word-of-mouth communication. Thus, the impact of word-of-mouth is shaped by the presence of both trust and commitment.

H5

Credibility, benevolence and relationship commitment are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s positive word of mouth communication for the agency.

The potential to remain with or revisit a supplier is the definition of Repurchasing intention given by Lee, Eze & Ndubis50. In a study by Erciş et al., repurchasing intention were consequence of trust and commitment. In their study, they proposed that both trust and commitment influence the future intentions of an exchange partner. Their study was conducted in the nonprofit university context to entail future attendance, subscription, and donation using high and low relational customers. They found that the future intentions of high relational consistent subscribers are driven by trust and commitment, not satisfaction51. Numerous scholars have posited that the trust can enhance their engagement with the suppliers for information-seeking and their propensity to repurchase. This trust-commitment is a critical factor that encourages customers to engage in past transactions. Agag contended that the probability of customers choosing to make repeat purchases is significantly affected by their level of confidence in the supplier’s ability to securely deliver products and responsibly manage their personal data52.

In our research, the concept of “repurchase intentions” is operationalized as the probability of tourists returning to and favoring a service provider in both the immediate and extended timeframes. We propose the hypothesis that the variables of trust and commitment are positively associated with the intentions of tourists to make subsequent purchases. In line with past studies, the presence of trust and commitment are instrumental in fostering the success of relationship marketing initiatives, and customer’s repurchase intentions with the agency. The Following hypothesis is formulated:

H6

Credibility, benevolence and relationship commitment are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s repurchase intentions with the agency.

Most tourism agents are realizing the significance of maintaining committed relationships with their loyalty customers. According to Jost, commitment is primarily reflected by one customer’s reluctant to switch to another provider53. Organizational behavior theorists believe that reluctance to change can be measured by the strength of customers’ involvement in and persistent with a provider54. Baumann, Elliott, & Hamin believes that the tendency of a committed customer is to oppose altering their preference55; however, this assumption has seldom been considered in consumer research. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H7

Credibility, benevolence and relationship commitment are significant and positive predictors of the customer’s reluctance to change the agency.

Research method

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant ethics guidelines and regulations. All survey methods and materials were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Three Gorges University and Chongqing Jiaotong University. All the participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Research methodology

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, which combining quantitative data obtained through simultaneous multiple regression analysis and qualitative data obtained through thematic coding. This approach was chosen because the mixed methods could complement and strengthen each other, and thus enhance the validity of the study56. It is a widely used approach in tourism and social research.

Quantitative survey

Participants

China Youth Travel Service (CYTS) Co., Ltd and China International Travel Service (CITS) Co., Ltd are two famous Integrated travel service providers in China. They launched mountaineering tourism service in Chongqing and the whole western region of China. CYTS has 78 branches and 1278 employees in Chongqing, CITS has 101 sale networks and over 2,000 employees. The two companies are famous mountaineering service providers including mountaineering tourism plan, Mountaineering equipment, mountaineering guide, and training, etc. 240 existing customers of each company will be surveyed through questionnaire surveys, together with interviews.

Instruments

The self-developed questionnaire consists of four main parts, which are described as follows.

-

(1)

Ecological values Survey. Ecological values Survey was adapted from Fulton et al.’s wildlife assessment to capture the tourists’ ecological values and the tourists’ perception of the company’s ecological values11, so that a “shared values” score could then be computed. Shared ecological values are those values held in common between two parties: mountaineering tourists and travel agencies. In order to capture ecological values under a mountaineering context, the values orientation approach used by Fulton et al. was adopted and their basic belief items were modified to reflect natural-based recreation generally and mountaineering tourism specifically. This construct was measured through the using of a dual sided, 20 item, 5-point Likert-type scale, that ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Customers’ ecological values were measured on one side of the scale and the customers’ perceptions of the travel agency’s ecological values on the other (see Supplementary Table S1). Then, 20 items subscale were extracted because their factor loadings were above 0.60.

-

(2)

Trust and relationship commitment Scale. Customer trust was examined from two dimensions. The first dimension, credibility, was measured using a seven-item index modified from Ganesan’s and Palácios et al. work57,58. The reliability for Ganesan’s scale was reported to range from 0.80 to 0.90. The index included such items as, “The promises made by this travel agency are trustworthy and reliable” and “This travel agency is open in trading with us.” The second dimension of trust was benevolence. Benevolence was measured using a five-item index, which included such items as, “In the past, this travel agency has made many sacrifices for me” and “In times of need, this travel agency has gone above and beyond for me.” The reliability for the scale was reported to range from 0.76 to 0.88. Each item was assessed using a six-point Likert-type scale. The answers for the items were averaged to obtain index scores for the credibility and benevolence.

Relationship commitment was measured using an index modified from Garbarino and Johnson together with Khan et al.40,59. The reliability for the scale was reported to be 0.87. Examples of the modified items include, “I am very committed to the relationship I have with this agency” and “This connection I have with this company is very close, like family members”. Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale.

-

(3)

Behavioral intention scale. This part focused on selected outcomes surveys (i.e., collaboration, word of mouth, repurchasing intentions, and reluctance to change).

Collaboration consists of organizing groups and giving feedback. Organizing groups and giving feedback were assessed through a scale adapted from Baloglu60. The scale has reported reliability ranging from 0.72 to 0.89. Examples of adapted items include, “I would permit my name and a positive comment I made about this agency to be used in an advertisement” and “If I encountered an idea that I liked at another agency, I would be willing to share it with the management or employees of this agency”.

Word-of-mouth communication was assessed using a three-item index modified from Baloglu’s study60. Word-of-mouth communication was measured using items such as, “I recommend this travel agency to my friends” and “I recommend this agency to individuals who seek my advice about mountaineering trip.” Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Repurchase intentions were assessed using a three-item index modified from Lee, Eze, & Ndubisi50. Repurchase intentions were measured by asking participants such questions as “I plan to go climbing with this travel agency again” and “I Plan to take more climbing trips with this travel agency in the future.” The reported reliability for this index prior to its adaptation for use in this study was 0.75. The answers for the four items were averaged to obtain an index score for future intentions.

The construct of reluctance to change was measured by adopting a four-item index modified from previous literature53. Items such as“I am not easily willing to change my preference to raft with this travel agency. and “Even if close friends recommended another agency, I would not change my preferences for this agency” are examples of those adapted for the questionnaire. The reported reliability for this scale before being adapted for this study was 0.81. Answers for the four items were averaged to obtain an overall index score. Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale.

-

(4)

Open-ended questionnaire. The fourth section, contained questions included at the end of the questionnaire. These scales were developed specifically for this study. Questions focused on such things as: their understanding of Mountaineering tourism, the differences between mass tourism, important factors while service provider selection and important attributes contributing to long-term relationship development. Participants were asked to “Please list some important factors to consider while choosing a mountaineering tourism service provider” and to “What do you see as the most important factors influencing your collaboration with this Mountaineering tourism provider in the future and why.”

Participants and data collection

The research sample of this study consisted of Chinese tourists who had purchased a mountaineering trip from these two firms: CYTS and CITS. To ensure sample independence and representativeness, 6 branches of each company were selected as research sites, and they were in various districts of Chongqing province.

During summer holiday, From July 29th to August 4th, 2023, an on-site investigation was implemented at these branches. 24 well-trained undergraduates majoring in tourism management were chosen as investigator to collect the tourists’ data on the spot. Random sampling was employed to collect data for ensuring generality and universal of the sample. Before the survey, all the participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Data analysis

A codebook was developed, assigning numerical scores to each item. These scores were then entered into SPSS. Frequency analyses and descriptive statistics were used to profile the study participants.

Validity and reliability of the scales used in the study were assessed by using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and alpha if item deleted coefficients. To ensure that the independent variables were not too highly correlated with the others, a bi-variate correlation matrix was constructed.

Simultaneous multiple regression analysis was used to analyze the hypothesized relationship between interval-scaled variables. Relationships between variables were considered statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Qualitative survey

Participants

An open-ended follow-up qualitative survey was conducted after the quantitative phase, the aim was to gain further insight into the data obtained during the quantitative phase. The participants are those who were willing to answer additional questions about their attitude toward mountaineering trips. Finally, 5 participants of each branch, and 60 respondents were invited to participate in this survey.

Questionnaire protocol development

The qualitative phase’s open-ended questionnaire survey was informed by the findings of the initial quantitative research. 10 open-ended questions were designed to gather additional data about tourists’ opinions of tourism service provider selection and relationship development. Among them, four questions explored participants’ understanding of mountaineering tourism, another two investigated their selection preference, and the last four items were used to measure factors contributing to long-term behavioral intentions (see Supplementary Table S2). This questionnaire protocol was pilot-tested among ten tourism professionals to ensure validity.

Data collection and analysis

The open-ended questions were printed and distributed to the participants on spot, and all participants completed the interviews on a voluntary basis. The collected data was subsequently analyzed using a thematic coding approach. Themes were identified based on the factors studied, and the most frequently mentioned themes and similarities among themes provided additional support for the quantitative results. Member checking was also used to further validate the responses, in conjunction with the quantitative findings.

Results

Sample description

After a week of field research, the researchers collected 40 questionnaires at each branch, and finally received 480 questionnaires. Of these, 240 were from company A and another 240 were from company B. Through data reviewing and screening, 44 questionnaires were discarded because most critical questions were left blank. Finally, 215 valid questionnaires from company A and 221 valid questionnaires from company B were qualified and sent to further analysis, resulting in a rate of 90.8%. The details of the sample description could be seen in following Table 2. Male participants occupied 55.7% and female ones occupied just 44.3%, indicating that male tourists prefer mountaineering tourism. The most frequently reported age group 21–30 years (43.1%), followed by 18–20 years (28.2%) and 31–40 (18.8%), reflecting that mountaineering trip was most popular among young and middle-aged populations.

Scales of measurement

This study utilized scales to measure three types of constructs: ecological values, relationship characteristics, and relationship outcomes. The following section will focus on the reliability analysis of the scales used in the study and the assessment of scale items.

Shared ecological values scale

The ecological values scale initially consisted of five distinct indices: ecological use, ecological experience, ecological education, ecological existence, and ecological activity. The first application of this scale was to measure tourists’ ecological values, while the second application was to measure tourists’ perceptions of the travel agency’s’ ecological values. However, seen from Supplementary Table S3, two of these indices, ecological use and ecological activity, were excluded from the study due to a low Cronbach’s alpha.

In testing the tourists’ ecological values scales, ecological education, ecological experience, and ecological existence demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.669, 0.725, and 0.755, respectively (see Supplementary Table S3).

Similarly, in testing the travel agency’s’ ecological values scales, ecological existence, ecological experience, and ecological education showed acceptable levels of reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.759, 0.776, and 0.702, respectively (see Supplementary Table S3).

-

(1)

Assessment of Tourists’ and travel agency’s’ Ecological values.

Three separate indices, namely Ecological experience, Ecological education, and Ecological existence, were used to assess ecological values. These values were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, where (1) represented “Strongly disagree,” and (5) represented “Strongly agree”. Table 3 provides a summary of the Tourists’ Ecological values Scale Items as well as tourists’ perception of travel agency’s’ Ecological values Scale Items.

Table 3 Ecological values scale items. From Table 3, it can be observed that both tourists’ ecological values and their perceptions of the travel agency’s’ ecological values are very similar. Tourists perceived both travel service providers’ have the same highest item score in each ecological values index. The highest overall mean among the items in the three indices was slightly higher for tourists regarding Ecological experience, "I appreciate the ecological environment when I go out for climbing" (4.813 for tourists vs. 4.713 for travel agency). The lowest overall mean on both scales was for the item "Some of my most unforgettable moments occurs when I saw some ecological environment that was unexpected” (4.346 for tourists vs. 4.369 for travel agency).

-

(2)

Shared Ecological values.

To calculate a “shared values” score, a simultaneous multiple regression was conducted using tourists’ ecological values to predict their perception of the travel agency’s’ ecological values. For each case, a predicted ecological values score was determined based on the regression equation. The residual for each case was saved as the measure of change (Table 4). The absolute values of the residuals were then used as the “shared values” score since they are not correlated with the predictor variable. By using the residuals to measure the difference between tourists’ ecological values and their perceptions of the travel agency’ ecological values, the study achieved the variance that remains unaccounted for after considering tourists’ ecological values. The absolute values of the residuals were used because the study aimed to measure the level of agreement/disagreement between tourists’ ecological values and their perceptions of the providers’ ecological values. Whether tourists’ or providers’ values were higher was irrelevant for this study. The absolute value assesses the distance from complete agreement.

Table 4 Descriptive of residuals (absolute values).

Trust-commitment scales

Scales measuring credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of over 0.80. Therefore, all scales were deemed acceptable and used in this study. The assessment of Credibility, Benevolence, and Commitment can also be seen in Supplementary Table S4., with the overall scale mean of 4.36, 3.62, and 3.49, respectively.

Behavioral intention scales

The scale measuring cooperation had a marginal but acceptable Cronbach’s alpha of 0.693. The relationship outcomes of word of mouth, future intentions, and reluctance to change demonstrated Cronbach’s alphas of over 0.80 (see supplementary Tables S5). The assessment of word of mouth, future intentions, and reluctance to change can also be seen in Supplementary Table S5., with the overall scale mean of 4.36, 3.26, and 3.499, respectively.

Hypothesis testing

In this section, seven hypotheses were tested to examine the influence of tourists’ perceptions of shared ecological values with the provider on their relationship with the provider and the outcomes of such a relationship. A series of standard multiple regression models were developed to identify relationships between these factors.

Test of hypothesis one

To test hypothesis 1, a simultaneous multiple regression was used to examine the effect of shared ecological values on credibility. Credibility was the dependent variable, and the three measures of shared ecological values were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 5 reveal that the regression model, consisting of three shared ecological values, significantly predicted tourists’ perception of the provider’s credibility (F3,436 = 4.981, p = 0.003). The three independent variables explained 3.6% of the variance in credibility. The results further indicated that two of the ecological values, ecological experience (β= -0.099) and ecological existence (β= -0.127), were negative predictors of credibility. Ecological education was not found to be significant predictors. The independent variable of ecological existence accounted for 4.1% of the variance in credibility. These outcomes reject H1, suggesting the discrepancy between share ecological values and tourists’ trust in the provider’s credibility.

Test of hypothesis two

To test hypothesis 2, a simultaneous multiple regression was used to examine the effect of shared ecological values on benevolence. Benevolence was the dependent variable, and the three measures of shared ecological values were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 6 revealed that the regression model, consisting of three shared ecological values, did not significantly predict tourist benevolence (F3,436 = 1.151, p = 0.0392). The results failed to provide support for Hypothesis 2, suggesting that the tourist’s perception of the provider’s benevolence is not influenced by the shared ecological values of ecological experience, ecological education, or ecological existence.

Test of hypothesis three

To test hypothesis 3, a simultaneous multiple regression was used to examine the effect of shared ecological values, tourist credibility, and benevolence on relationship commitment.

As shown in Table 7, the regression model, consisting of three shared ecological values, credibility, and benevolence, significantly predicted relationship commitment (F3,436 =152.011, p = 0.000). The five independent variables explained 67.1% of the variance in relationship commitment. The results further indicated that credibility (β = 0.261) and benevolence (β = 0.684) were significant predictors of relationship commitment, while shared ecological values were not.

Credibility alone accounted for 7.1% of the unique variance explained, and benevolence accounted for 5.3%. These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 3, suggesting that credibility and benevolence are significant predictors of relationship commitment. This implies that tourists are more likely to maintain a relationship with a provider if they perceive them as credible and having their best interests in mind.

Test of hypothesis four

To test hypothesis 4, a simultaneous multiple regression was used to examine the effect of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment on Collaboration. Collaboration was the dependent variable, while credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 8 revealed that the regression model, consisting of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment, significantly predicted Collaboration (F3,436 = 181.913, p = 0.000). The three independent variables explained 61.1% of the variance in cooperation. The results further indicated that all three independent variables, credibility (β = 0.237), benevolence (β = 0.118), and relationship commitment (β = 0.526), were significant predictors of Collaboration. Credibility accounted for 5.9% of the variance, benevolence accounted for 5.7%, and relationship commitment accounted for 5.1% of the variance explained in cooperation.

These results provide support for Hypothesis 4, suggesting that cooperation between a tourist and provider can be enhanced through the development of tourist trust (credibility and benevolence) and relationship commitment.

Test of hypothesis five

To test hypothesis 5, a simultaneous multiple regression was used to examine the effect of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment on word of mouth. Word of mouth was the dependent variable, while credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 9 revealed that the regression model, consisting of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment, significantly predicted word of mouth (F3,436 = 160.673, p = 0.000). The three independent variables explained 55.9% of the variance in word of mouth. The results further indicated that two independent variables, credibility (β = 0.599) and relationship commitment (β = 0.283), were significant predictors of word of mouth. Credibility accounted for 5.3% of the variance, and relationship commitment accounted for 4.5%.

These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 5, suggesting that the tourist’s perception of the provider’s credibility and the development of committed relationships with tourists can enhance word of mouth communication.

Test of hypothesis six

To test hypothesis 6, a simultaneous multiple regression was adopted for analyzing the effect of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment on repurchase intentions. Repurchase intentions were the dependent variable, while credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 10 revealed that the regression model, consisting of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment, significantly predicted repurchase intentions (F3,436= 169.501, p = 0.000). The three independent variables explained 58.1% of the variance in future intentions. The results further indicated that two independent variables, credibility (β = 0.516) and relationship commitment (β = 0.424), were significant predictors of repurchase intentions. Credibility accounted for 5.9% of the variance, and relationship commitment accounted for 4.9%.

These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 6, suggesting that a tourist’s intentions to purchase from the same provider in the future can be enhanced through the development of the tourist’s perception of the provider’s credibility and through the development of committed relationships with tourists.

Test of hypothesis seven

To test hypothesis 7, a simultaneous multiple regression was also adopted to analyzing the impact of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment on reluctance to change. Reluctance to change was the dependent variable, while credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment were the independent variables.

Results shown in Table 11 revealed that the regression model, consisting of credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment, significantly predicted reluctance to change (F3,436= 199.374, p = 0.000). The three independent variables explained 62.9% of the variance in reluctance to change. The results further indicated that two independent variables, credibility (β = 0.301) and relationship commitment (β = 0.493), were significant predictors of reluctance to change. Credibility accounted for 6.2% of the variance, and relationship commitment accounted for 5.2%.

These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 7, suggesting that a tourist’s reluctance to change providers can be enhanced through the development of the tourist’s perception of the provider’s credibility and through the development of committed relationships with providers.

Qualitative phase

This part analyzed respondents’ interview related to mountaineering tourism suppliers’ selection and relationship development. Thematic coding was adopted for analyzing respondents’ response. Themes were identified by reviewing each respondents’ answers and generating inductively from the raw data. The responses were faithfully recorded and subsequently divided into pieces for coding and interpretation. Initially, main themes were identified according to the study variables and interview responses. Based on responses as well as open-ended questions, three main themes were identified: Mountaineering tourism, provider selection, and relationship development. Following a thorough review of the individual transcripts, the research team collectively discussed and established sub-category codes, achieving a unified agreement on the themes among all contributors. This ongoing process of refinement shaped the coding framework, resulting in the emergence of nine distinct sub-themes spread across three different categories. Additionally, member checking was utilized to validate the responses. Coding scheme as well as influencing factors developed for examining the response data are presented in Table 12.

Mountaineering tourism

Majority of respondents stated that Mountaineering tourism refers to the activity of traveling to and experiencing mountains, typically involving climbing and hiking in mountainous regions. And based on the content analysis of responses the outstanding advantages of Mountaineering tourism lies in that it combines adventure, physical exertion, and enjoyment of natural beauty.

Their ecological-related activities may include Garbage classification and storage, no littering, flowers and plants caring, Wildlife Protection, recycling, Respecting for local culture and history, and do not damage historical relics and cultural relics, and so on. Additionally, 49 male respondents stated that the improvement of mountaineers’ ecological awareness has led to higher expectations for tourism providers to adopt environmentally friendly and ecological concepts. When choosing suppliers, they may place greater emphasis on whether they share a common ecological value perspective. In specific, 55 out of 60 mentioned that it plays an important role of their decision-making whether the suppliers hold concept of ecological environment protection. As to the key factors while selecting suppliers, respondents frequently prioritize safety and engage in responsible ecological practices. As with any outdoor activity, preparation, proper equipment, experienced guides, and adherence to environmental regulations are crucial for ensuring a positive and sustainable experience. And keywords frequently mentioned are credibility, responsibility, philanthropy and sustainability. This finding was proved to be consistent with Hypothesis 3.

Through semi-interview, 32 out of 60 responded that the key differences between mountaineering tourism and mass tourism was that the former one emphasized more on ecological environmental protection. In addition, this form of tourism often involves specialized equipment, such as climbing ropes, harnesses, crampons, and ice axes. It requires knowledge and skills related to rock climbing, navigation, wilderness survival, and altitude acclimatization.

Factors influencing mountaineering tourism provider selection

The factors here refer to the reasons of why choose this mountaineering tourism provider. And the respondents’ replies encompass variety of incentive factors, including reputation, expertise and experience, safety measures, transaction cost, customization and flexibility, ecological awareness, client reviews and feedback, accessibility and logistics, and support Services. Among them, 93.3% (56 out of 60) mentioned credibility. In other words, the priority criterion for a choosing a mountaineering provider was credibility, in specific, providers’ business reputation, trustworthiness, and reliability in offering safe and high-quality mountain adventure experiences. As one middle-aged tourist stated “Credibility encompasses the provider’s ability to deliver on their promises, adhere to safety standards, and provide a positive tourist experience”, this statement was further supported by other similar responses, which stated that the following factors: experience and expertise, safety measures, legal compliance, positive reviews and recommendations, environmental and ecological considerations have in fact positive influence tourists’ pre-purchase decision making. Among them, majority of them choose environmental and ecological considerations (49 out of 60), which is a direct reflection of improvement environmental awareness of the audience and it is also an important role for improving brand image as well as reducing operation costs. These statement all have proved that credibility was important predictor for tourists’ purchasing, which is consistent with H3.

The second main driver was cost. More than half (41 out of 60) noted that expenditure was becoming more important in shaping tourists’ supplier selection. Based on one young respondent’ comment “In addition to caring for the credibility, if one Mountaineering tourism supplier could enable tourists to enjoy more beautiful mountains at an affordable price. This could increase tourists’ psychological satisfaction and emotional belongings, which would enhance tourists’ confidence of the supplier. As to the reasons, as one respondent noted, Mountaineering adventure is still at the early stage of development, the operation cost of this tourism programs was so high, and the pricing mechanism is also not open and transparent. Thus, it is also an important factor which should be taken into consideration.

The third influencing factor was benevolence, which was a value of putting tourists’ interests above own. It is a valuable and scarce kindness of organization. 29 out of 60 cited that donation, community service, training of ecological knowledge for tourists, ecological foundation establishment, advocating low-carbon life, all these kindness activities have left an unforgettable impression among the audience. People prefer to choose the supplies of good reputation and brand image. This is also consistent with H3.

Factors influencing long-term relationship development

The third theme of qualitative analysis was attributes of future behavioral intention. Respondents were asked to point out the factors influencing their collaboration, WOM, repurchasing intention and reluctance to change, respectively. Through content analysis of answers, two interesting findings emerged.

Firstly, credibility and relationship commitment are frequently mentioned, almost every response has mentioned the importance of them. In details, expressions such as reputation, trustworthiness, reliability, experience and expertise, safety measures, legal compliance, positive reviews and recommendations, environmental and ecological considerations were mentioned by more than 95% of respondents. No doubt, credibility and relationship commitment were indeed important factors contributing to tourists’ long-term collaboration, WOM as well as repurchase intention. As one female participant responded that “the brand image of credibility and responsibility have reduced the doubts of consumers and provided tangible guidance for future actions”, thus the image of credibility was the foundation for tourists’ future intention. Similarity, the harmonious and intimate relationship between tourists and business forms a solid foundation of future commercial behavior. Thus, more than two thirds (45 out of 60) highlighted the role of relationship commitment. This finding is consistent with above hypotheses 4 to 7, which indicated that both credibility and relationship commitment were positively predictors of future behavioral intention.

Secondly, only relationship commitment and credibility were not enough, and 20% of the respondents remarked that the role of benevolence cannot be ignored. As one noted: “Only relationship commitment and credibility were not enough, and providers should provide an image of kindness, charity and goodwill, it should be a representative of cause-related tourism”. Besides, two elder participants added that benevolence was only a public relations image of the supplier to the public audience, it is not closely related with real transaction, and this psychological suggestion has little influence on the future relationship development of tourists. This outcome was an important supplementary for the quantitative testing, indicating that benevolence was only important in predicting tourists’ collaboration, while not played an important role in predicting tourists’ business transaction behavioral intentions including repurchasing and reluctant to change in the future.

Conclusions and recommendations

Hypotheses outcomes

This part reported the outcomes of the hypotheses testing. Of the seven hypotheses, only H3, H4, H5, H6 and H7 were proved to be supported, or partially supported. In specific, the degree to which tourists value the existence and experience of the ecological environment was shown to negatively predict the tourists’ feelings that the provider is credible. In addition, credibility and benevolence were shown to be significantly positive predictors of the tourist’s commitment to their relationship with the provider. The outcomes of collaboration, word of mouth, repurchase intention and reluctance to change were all significantly and positively related to credibility and relationship commitment. Table 13 presented the outcomes of the hypotheses testing.

Conclusions and discussions

The study aimed to examine the role of shared ecological values, trust, and relationship commitment in developing relationships between Mountaineering tourism providers and their tourists. The following made an analysis and discussions of this finding with previous research outcomes.

Antecedents of buyer-supplier relationship

According to Morgan and Hunt, companies that prioritize collaborating with tourists and business partners who align with their values can cultivate trust and strengthen commitment in their relationships26. Besides, they also found that shared values were the only factor contributing to trust and relationship commitment. However, in our study, Morgan and Hunt’s findings were not supported. It is interesting to note that the following two sub-dimensions of shared ecological values, ecological existence and ecological experience were slightly negative predictors of credibility. As to the reasons, firstly, At the current stage of China’s economic development, the majority of businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises and their local branches, prioritize profit above all else, often treating Ecological protection as nothing more than a marketing slogan61. This mindset may lead to the perception that travel agencies’ environmental initiatives are primarily profit-driven rather than stemming from a genuine concern for the environment, which in turn can undermine their credibility62. If a travel agency highlights its environmental practices in its promotional materials but fails to take meaningful action, it may prompt tourists with ecological awareness to question the agency’s credibility. The second issue is the discrepancy between expectations and reality. Tourists with extensive ecological experience may have higher expectations for the natural environment63. If they perceive that the tourism agencies’ performance in ecological protection falls short of their expectations, it can cast doubt on the agencies’ credibility. These individuals might be more attuned to environmental issues and, as a result, may be more critical of tourism companies’ environmental impacts, leading to skepticism about their environmental claims. The third sub-dimension of shared ecological values, shared ecological education has not been proved a positive predictor of credibility because the primarily purpose of mountaineers focused on adventure rather than education64. Therefore, Mountaineering adventure tourists may not place an emphasis on educational function while evaluating the reliability of the company.

Furthermore, shared ecological values, including ecological experience, ecological education, and ecological existence were not proved to be a significant and direct predictor of benevolence or relationship commitment under the context of this research. The reasons underlying the phenomenon lies in that benevolence was not considered as crucial for Mountaineering tourists’ provider selection in the adventure travel industry. On the one hand, Mountaineering tourism is seen as inherently risky, and tourists prioritize the assurance of safe and professional trips when evaluating providers, rather than the benevolence. On the other hand, as a customer, it is challenging to evaluate providers’ benevolence through limited business interaction. Since most Mountaineering tourists do not make frequent visits to the travel agencies, it becomes very difficult to assess agencies’ strategic vision and intrinsic intent, which are essential in assessing benevolence65.

Additionally, trust, a key determinant of relationship commitment, has been extensively examined by various authors, including Morgan and Hunt, Wang et al., Afsar et al. and Dunaetz et al.26,28,29,30. And in this research, trust was measured using two dimensions in our research: credibility and benevolence, it was also proved to be a prerequisite for relationship commitment between tourists and providers, which was consistent with notions held by several previous authors66,67,68. The reason behind this was that perceived risk associated with adventure tourism extends beyond financial and temporal considerations to include physical well-being. The exaggerated risk perception underscores the importance of provider credibility and benevolence in fostering tourist-provider relationships. This concept might be magnified in industries like Mountaineering tourism, which are not only risky due to the nature of the service being difficult to evaluate before purchase but also because they involve an inherently dangerous activity. Thus trust, measured by credibility and benevolence, was proved to be positive predictor of supplier-buyer relationship development.

These findings bear significant implications in the domain of buyer-supplier relationship development, particularly in the setting of mountaineering tourism, which is perceived as high-risk by tourists.

Outcomes of buyer-supplier relationship

Cui et al. claimed that trust and commitment can distinguish tourists seeking short-term transactions from those interested in long-term relationships45. While some authors contend that trust and commitment are desirable outcomes in themselves26,45, this study investigates four potential outcomes associated with their development. These benefits include cooperation, word of mouth communication, future intentions, and reluctance to change.

Collaboration, defined in this study as buyer-supplier working together to achieve mutual goals, is the only relationship outcome significantly and positively predicted by credibility, benevolence, and relationship commitment. This suggests that tourists are more inclined to cooperate with providers who demonstrate the ability and intention to fulfill promises, prioritize their best interests, and have established a committed relationship. This finding aligns with Moirano et al. and Morgan and Hunt’s discovery that collaboration directly results from both trust and relationship commitment26,46.

Word-of-mouth communication is positively predicted by two factors including credibility and relationship commitment. This finding emphasizes the importance of provider’s expertise and reliability in performing the job effectively and foster committed relationships with tourists. These results are consistent with Berger, where positive WOM was strongly correlated with buyer-supplier relationship, which in turn are highly associated with trust49.

Repurchasing Intentions are also positively predicted by credibility and relationship commitment. This finding stresses the importance of suppliers’ abilities of fulfilling their responsibilities and cultivating committed relationships with tourists. The study’s results align with Erciş et al.‘s assertion that trust and commitment are pivotal in distinguishing between consumers who prefer fleeting engagements and those who are invested in enduring connections51. Their research indicated that the ongoing engagement of deeply committed patrons is primarily influenced by their levels of trust and commitment.

Reluctance to change is also positively predicted by credibility and relationship commitment. It implies that tourists are less likely to alter their preferences when they perceive service providers as both competent and committed to honoring their commitments, and when a strong relationship exists between the tourist and the provider, regardless of external lures. These results are proved to be consistent with Jost and Shimoni, who argued that committed tourists tend to resist altering their preferences53,54.

It is worth noting that benevolence did not exhibit a substantial correlation with word of mouth, future intentions, or reluctance to change. This observation is consistent with the studies by Ganesan’s and Palácios et al.57,58, who similarly observed no significant link between benevolence and a long-term relationship development.

Managerial implications

Given the increasingly intense market competition and constantly evolving economic circumstances faced by the tourism enterprises, maintaining viability requires gaining a competitive advantage. As to the tourism suppliers, an important way to gain the advantage was through establishing long-term relationship with high-end tourists of shared values69. This study hypothesized that shared ecological values serve as significant precursors to buyer-supplier relationship development, and it also investigated the outcomes of relationship development.

Tourists with strong trust-commitment relationship with suppliers are known to travel more, spend more, have higher levels of education, and are more likely to develop relationships with providers70. The findings of this study indicate that one approach for providers to acquire and retain tourists is to cultivate trust-committed relationships with high-value tourists. Therefore, providers must work on developing their credibility in the eyes of tourists to enjoy the associated benefits. For instance, providers should first offer tourists exceptional value services, which include professional proficiency and efficient execution in areas such as tour route planning, ticketing services, hotel reservations, and tour guiding. Secondly, constructing and maintaining sound customer relationships is crucial for enhancing reliability. This involves an in-depth comprehension of customer demands, provision of quality service throughout the entire process, regular follow-up visits, and establishment of trust relationships. Additionally, establishing a customer feedback mechanism and promptly addressing customer issues and complaints, along with the ongoing optimization and refinement of service processes, are also crucial for enhancing reliability.

In addition, the findings suggest that ecological existence and ecological experience act as modest negative predictors of credibility. In light of these insights, travel agencies should consider more impactful and practical initiatives to bolster their image as stewards of ecological care. For example, they could showcase their environmental commitment by developing eco-friendly hiking itineraries, conducting environmental conservation workshops, and engaging in ecologically-focused public service projects, thereby underscoring their enduring dedication to ecological values71.

Therefore, trust and buyer-supplier relationship commitment are critical important for targeting and retaining potential tourists, understanding these concepts and how they can help providers attract a committed, high-end clientele can contribute to the desired competitive advantage.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of the present study are available within the article. Additional data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Wang, Y. et al. Comprehensive evaluation and prediction of tourism ecological security in droughty area national parks—A case study of Qilian Mountain of Zhangye section, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 16816–16829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-12021-2 (2021).

Zhong, L., Sun, S., Law, R., Li, X. & Deng, B. Health tourism in China: A 40-year bibliometric analysis. Tour Rev. 78(1), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2022-0112 (2023).

Cao, Q. et al. Tourism competitiveness evaluation: Evidence from mountain tourism in China. Front. Psychol. 13, 809314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809314 (2022).

Zeng, L., Li, R. Y. M., Nuttapong, J., Sun, J. & Mao, Y. Economic development and mountain tourism research from 2010 to 2020: Bibliometric analysis and science mapping approach. Sustainability 14, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010562 (2022).

Van Tonder, E., Fullerton, S., De Beer, L. T. & Saunders, S. G. Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: The role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. J. Retail Consum. Serv. 71, 103190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103190 (2023).

Ahmed, R. R., Streimikiene, D., Qadir, H. & Streimikis, J. Effect of green marketing mix, green customer value, and attitude on green purchase intention: evidence from the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 11473–11495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22944-7 (2023).

Li, M. W., Teng, H. Y. & Chen, C. Y. Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. J. Hosp. Tour Mang. 44, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.015 (2020).

Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour 31, 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091 (2023).

Bigné, E., Zanfardini, M. & Andreu, L. How online reviews of destination responsibility influence tourists’ evaluations: An exploratory study of mountain tourism. J. Sustain. Tour 28, 686–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1699565 (2020).

Casais, B., Fernandes, J. & Sarmento, M. Tourism innovation through relationship marketing and value co-creation: A study on peer-to-peer online platforms for sharing accommodation. J. Hosp. Tour Manag. 42, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.11.010 (2020).

Fulton, D. C., Manfredo, M. J. & Lipscomb, J. Wildlife value orientations: A conceptual and measurement approach. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 1, 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209609359060 (1996).

Abidin, Z. A. Z. & Jacobs, M. Relationships between valence towards wildlife and wildlife value orientations. J. Nat. Conserv. 49, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2019.02.007 (2019).

Jacobs, M. H., Vaske, J. J. & Sijtsma, M. T. Predictive potential of wildlife value orientations for acceptability of management interventions. J. Nat. Conserv. 22, 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2014.03.005 (2014).

Vaske, J. J., Jacobs, M. H. & Sijtsma, M. T. Wildlife value orientations and demographics in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 57, 1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0531-0 (2011).

Hermann, N., Voß, C. & Menzel, S. Wildlife value orientations as predicting factors in support of reintroducing bison and of wolves migrating to Germany. J. Nat. Conserv. 21, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2012.11.008 (2013).

Gigliotti, L. M. & Sweikert, L. A. Wildlife value orientation of landowners from five states in the upper midwest, USA. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 24, 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2019.1632991 (2019).

Manfredo, M. J., Teel, T. L. & Henry, K. L. Linking society and environment: A multilevel model of shifting wildlife value orientations in the western United States. Soc. Sci. Quart. 90, 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00624.x (2009).

Liordos, V., Kontsiotis, V. J., Eleftheriadou, I., Telidis, S. & Triantafyllidis, A. Wildlife value orientations and demographics in Greece. Earth. 2, 457–467. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth2030027 (2021).

Gamborg, C. & Jensen, F. S. Wildlife value orientations among hunters, landowners, and the general public: A Danish comparative quantitative study. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 21, 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2016.1157906 (2016).

Zinn, H. C. & Shen, X. S. Wildlife value orientations in China. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 12, 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701555444 (2007).

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R. & Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Mark. 57 (1), 81–101 (1993). http://www.jstor.org/stable/1252059

Doney, P. M. & Canno, J. P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J. Mark. 61(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100203 (1997).

Sycamore, R. Deconstructing volunteer tourism: Benevolence or self-serving altruism?. J. Paramed. Pract. 13(12), 523–525. https://doi.org/10.12968/jpar.2021.13.12.523 (2021).

Nguyen, N. Reinforcing customer loyalty through service employees’ competence and benevolence. Serv. Ind. J. 36 (13–14), 721–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2016.1272595 (2016).

Khairy, H. A. et al. The effect of benevolent leadership on job engagement through psychological safety and workplace friendship prevalence in the tourism and hospitality industry. Sustainability 15, 13245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713245 (2023).

Morgan, R. M. & Hunt, S. D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 58, 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302 (1994).

Ramkissoon, H. Social bonding and public trust/distrust in COVID-19 vaccines. Sustainability. 13, 10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810248 (2021).

Wang, X., Tajvidi, M., Lin, X. & Hajli, N. Towards an ethical and trustworthy social commerce community for brand value co-creation: a trust-commitment perspective. J. Bus. Ethics. 167, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04182-z (2020).

Afsar, B. et al. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 27, 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1806 (2020).

Dunaetz, D. R., Smyly, C., Fairley, C. M. & Heykoop, C. Values congruence and organizational commitment in churches: When do shared values matter?. Psychol. Relig. Spirit 14, 625–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000314 (2022).

Crotts, J. C., Coppage, C. M. A. & Andibo, A. Trust-commitment model of buyer-supplier relationships. J. Hosp. Tour Res. 25(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/109634800102500206 (2001).

Sin, L. Y., Tse, A. C. & Yim, F. H. CRM: Conceptualization and scale development. Eur. J. Mark. 39, 1264–1290. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510623253 (2005).

Kashyap, V. & Sivadas, E. An exploratory examination of shared values in channel relationships. J. Bus. Res. 65 (5), 586–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.008 (2012).

Yoganathan, D., Jebarajakirthy, C. & Thaichon, P. The influence of relationship marketing orientation on brand equity in banks. J. Retail Consum. Serv. 26, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.05.006 (2015).

Malla, S. S. & Malla, S. Does the perception of organizational justice determine employees’ affective commitment? The mediating role of organizational trust. Benchmarking. 30, 603–627. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2021-0408 (2023).

Nunkoo, R., Ramkissoon, H. & Gursoy, D. Public trust in tourism institutions. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 1538–1564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.04.004 (2012).

Ferro-Soto, C., Padin, C., Svensson, G. & Høgevold, N. The role of trust and commitment as mediators between economic and non-economic satisfaction in sales manager B2B relationships. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 38, 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2021-0076 (2023).

Curado, C. & Vieira, S. Trust, knowledge sharing and organizational commitment in SMEs. Pers. Rev. 48, 1449–1468. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2018-0094 (2019).

Nunkoo, R. & Ramkissoon, H. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 997–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.017 (2012).

Garbarino, E. & Johnson, M. S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 63, 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299906300205 (1999).

Sui Pheng, L. The extension of construction partnering for relationship marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 17, 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634509910271614 (1999).

Lumineau, F. How contracts influence trust and distrust. J. Manag. 43, 1553–1577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314556656 (2017).

Paluri, R. A. & Mishal, A. Trust and commitment in supply chain management: A systematic review of literature. Benchmarking 27, 2831–2862. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2019-0517 (2020).

Ashnai, B., Henneberg, S. C., Naudé, P. & Francescucci, A. Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: An attitude–behavior–outcome model. Ind. Mark. Manag. 52, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.020 (2016).

Cui, Y., Mou, J., Cohen, J., Liu, Y. & Kurcz, K. Understanding consumer intentions toward cross-border m-commerce usage: A psychological distance and commitment-trust perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 39, 100920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100920 (2020).

Moirano, R., Sánchez, M. A. & Štěpánek, L. Creative interdisciplinary collaboration: A systematic literature review. Think. Skills Creat. 35, 100626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100626 (2020).

Anderson, J. C. & Narus, J. A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 54, 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400103 (1990).

Choi, O. K. & Cho, E. The mechanism of trust affecting collaboration in virtual teams and the moderating roles of the culture of autonomy and task complexity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 91, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.032 (2019).

Berger, J. Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. J. Consum. Psychol. 24, 586–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002 (2014).

Lee, C. H., Eze, U. C. & Ndubisi, N. O. Analyzing key determinants of online repurchase intentions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 23, 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851111120498 (2011).

Erciş, A., Ünal, S., Candan, F. B. & Yıldırım, H. The effect of brand satisfaction, trust and brand commitment on loyalty and repurchase intentions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 58, 1395–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1124 (2012).

Agag, G. E-commerce ethics and its impact on buyer repurchase intentions and loyalty: An empirical study of small and medium Egyptian businesses. J. Bus. Ethics 154, 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3452-3 (2019).

Jost, J. T. Resistance to change: A social psychological perspective. Soc. Res. 82, 607–636. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2015.0035 (2015).

Shimoni, B. What is resistance to change? A habitus-oriented approach. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 31, 257–270. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0073 (2017).

Baumann, C., Elliott, G. & Hamin, H. Modelling customer loyalty in financial services: A hybrid of formative and reflective constructs. Int. J. Bank. Mark. 29, 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321111117511 (2011).

Östlund, U., Kidd, L., Wengström, Y. & Rowa-Dewar, N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48, 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.005 (2011).

Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 58, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800201 (1994).

Palácios, H., de Almeida, M. H. & Sousa, M. J. A bibliometric analysis of trust in the field of hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 95, 102944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102944 (2021).

Khan, I., Hollebeek, L. D., Fatma, M., Islam, J. U. & Riivits-Arkonsuo, I. Customer experience and commitment in retailing: Does customer age matter?. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 57, 102219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102219 (2020).

Baloglu, S. Dimensions of customer loyalty: Separating friends from well wishers. Cornell Hotel Restaur. A 43, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010880402431005 (2002).

Zhang, D., Lu, S., Morse, S. & Liu, L. The impact of COVID-19 on business perspectives of sustainable development and corporate social responsibility in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24, 8521–8544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01798-y (2022).

Tang, L. & Li, H. Corporate social responsibility communication of Chinese and global corporations in China. Public. Relat. Rev. 35, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.016 (2009).

Zhang, Q. & Xu, H. Understanding aesthetic experiences in nature-based tourism: The important role of tourists’ literary associations. J. Destin Mark. Manag. 16, 100429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100429 (2020).

Wilson, J. & Dashper, K. In the shadow of the mountain: The crisis of precarious livelihoods in high altitude mountaineering tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 2270–2290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2108038 (2022).

Anderson, B. Mountaineers in the City. Cities, Mountains and Being Modern in fin-de-siècle England and Germany 25–63 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Chapman, C. M., Hornsey, M. J. & Gillespie, N. To what extent is trust a prerequisite for charitable giving? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 50, 1274–1303. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211003250 (2021).

Bianchi, C. & Saleh, M. A. Investigating SME importer–foreign supplier relationship trust and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 119, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.023 (2020).

Barbalet, J. Brill. The experience of trust: Its content and basis, in Trust in Contemporary Society, 11–30 (2019).

Chaney, D. & Martin, D. The role of shared values in understanding loyalty over time: A longitudinal study on music festivals. J. Travel Res. 56, 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516643411 (2017).

Batat, W. The role of luxury gastronomy in culinary tourism: An ethnographic study of Michelin-starred restaurants in France. Int. J. Tour. Res. 23, 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2372 (2021).

Lee, T. H., Jan, F. H. & Liu, J. T. Developing an indicator framework for assessing sustainable tourism: Evidence from a Taiwan ecological resort. Ecol. Indic. 125, 107596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107596 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the articles for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72172021), Chongqing Talent Fundation (No.cstc2024ycjh-bgzxm0093), Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No.yjg223131), Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission(No.223297 and No. 243415), Higher Education Research Projects of Chongqing Three Gorges University (Nos.GJ202210 and JGSZH2202) and Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Research Program of Chongqing Three Gorges University (No. XYJG202305).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions