Abstract

The use of transaxillary and transsubclavian approaches for endoscopic thyroidectomy has increased globally. However, studies examining the comparative outcomes of these procedures are scarce. In this study, we aimed to compare the safety and efficacy of thyroidectomy between the gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transaxillary approach (GETTA) and gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transsubclavian approach (GETTSA) in patients with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC). Medical records of patients with PTC who underwent GETTA or GETTSA performed by the same surgical team between August 2022 and August 2023 were retrospectively reviewed. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to mitigate potential selection bias and adjust for baseline clinical characteristic differences. After PSM using 10 covariates, 196 patients (GETTA: 98; GETTSA: 98) were included. In comparison to the GETTSA group, the GETTA group exhibited a longer duration of operation (120.00 [103.75–140.00] vs. 110.00 [90.00–125.00] min, P = 0.001), longer postoperative hospital stays (1.00 [1.00–3.00] vs. 1.00 [1.00–2.00] days, P = 0.008), higher hospitalisation costs (23,973.02 [22,640.80–25,379.80] vs. 23,306.00 [21,968.97–24,070.68] Yuan, P = 0.015), and greater postoperative drainage (60.00 [50.00–70.00] vs. 46.50 [40.00–56.25] mL, P < 0.001). Intraoperative parathyroid autotransplantation and vocal cord paralysis rates were not significantly different between groups. The number of lymph node metastases via central lymph node dissection was not significantly different between groups (0.00 [0.00–1.00] vs. 0.00 [0.00–1.00], P = 0.645). No significant procedural safety or completeness differences were observed between GETTA and GETTSA. GETTA had better cosmetic outcomes. GETTSA had shorter duration of operation durations, shorter hospital stays, lower hospitalisation costs, and lower postoperative drainage, making it a better option for clinical use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cosmetic outcomes have always been an important consideration in thyroid and parathyroid surgeries owing to the visibility of the front of the neck and the higher incidence of thyroid disease in women1,2. Surgeons have sought ways to improve the cosmetic outcomes of these procedures. Traditionally, thyroidectomies have been performed through a transverse skin incision at the front of the neck. This has potentially led to scarring in the visible area, which may compromise the quality of life in patients after thyroidectomy3. Therefore, surgeons have developed various techniques to prevent neck-scarring. Moreover, in 1998, Shimizu et al. described the first video-assisted endoscopic thyroid and parathyroid surgeries by performing laparoscopic thyroid surgery using a subclavian approach4. The procedure, named the ‘video-assisted neck surgery’, uses a gasless skin-lifting technique to create a working space by lifting the skin and creating an open wound without introducing carbon dioxide. In 2021, Zhang et al. improved the gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transsubclavian approach by refining the incision position, surgical pathway, and instruments5. This improved technique was successfully used to treat unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma, achieving surgical safety and complete tumour removal5. Furthermore, the gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy (GETTA) approach was first proposed by Yoon et al.6in 2006. After being modified by Zheng et al. and introduced in China7, GETTA gained popularity owing to its short learning curve and operating time. Zhu et al. indicated that endoscopic thyroidectomy via the axillary or subclavicular approach for the treatment of PTC was safe and feasible, with no significant difference in the number of central lymph nodes dissected compared to conventional open surgery8. However, the central neck exposure rate for the axillary approach (83.1%) was significantly lower than that for the subclavicular approach (GETTSA) (100%; P = 0.008)8. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to preliminarily investigate the surgical outcomes of gasless transaxillary versus subclavian endoscopic surgery for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) by comparing GETTA with GETTSA.

Methods

Patients and study design

This retrospective study was conducted in the Department of Thyroid Surgery at The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University. The study analysed 351 patients with PTC who underwent surgical treatment by the same team in our department between August 2022 and August 2023. The study included 98 patients who underwent gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transaxillary approach (GETTA group) and 253 who underwent gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transsubclavian approach (GETTSA group). Before surgery, all patients were provided with clear explanations of all available thyroidectomy methods using multimedia. The patients were free to choose their preferred thyroidectomy method. Due to the need for cosmetic interventions, young women tended to opt for transaxillary or transsubclavian thyroidectomy, as opposed to traditional open surgical methods.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

After careful evaluation, patients in both groups met the following inclusion criteria: (a) the same surgical team, (b) first-time thyroid surgery, (c) postoperative pathological confirmation of PTC, (d) unilateral radical thyroid cancer, (e) PTC diameter < 4 cm, and (f) strong cosmetic needs in the neck. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) history of neck surgery, (b) history of neck radiation therapy, (c) lateral neck lymph node metastasis, (d) tumour invasion into adjacent organs, and (e) combined distant metastasis.

Surgical procedure

All surgeries involved unilateral thyroid lobectomy, isthmus resection, and ipsilateral central zone lymph node dissection, all of which were performed by the same surgical team.

Surgical procedure for GETTA

The surgical technique for GETTA has been previously described in detail9 and mainly referenced the GETTA procedure of Zheng et al.10 The patient was placed in the supine position and administered general anaesthesia. The neck was tilted backwards and the head to the contralateral side. A 5-cm incision was made along the natural fold of the axillary region, at either the first or second fold, with the anterior end of the incision not extending beyond the anterior axillary line(Fig. 1A); the skin and subcutaneous tissue were incised down to the surface of the pectoralis major muscle. Thereafter, a flap was created along the sarcolemma of the pectoralis major muscle, bound inferiorly by the sternal heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and superiorly by the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the SCM. The flap was then elevated upwards, and the endoscope was introduced. The dissection of the surface of the pectoralis major muscle was continued under endoscopic guidance. Furthermore, by separating the sternal head of the SCM from the clavicular head in an upward and downward direction, a specialized endoscopic retractor was inserted to lift the sternal head to expose and free the scapulohyoid muscle.The endoscopic atraumatic forceps were used to elevate the strap muscles, while alternating between the ultrasonic scalpel and the endoscopic dissector to carefully separate the deep surface of the strap muscles. Adjusted the retractor to further elevate the strap muscles in the anterior part of the neck, exposing the thyroid (Fig. 1B). The upper pole was thoroughly explored, grasped, and drawn towards the operator before resection to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. After suturing the vessels of the upper part of the thyroid gland, the upper parathyroid gland was carefully identified and preserved in situ on the dorsal side of the thyroid gland (above the inlet of the laryngeal nerve). The parathyroid gland was separated from the thyroid gland, and its blood supply was protected. The lower parathyroid gland, connected to the thymus, was preserved. The middle thyroid veins were closed using a harmonic scalpel. Additionally, after identifying and isolating the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and parathyroid gland, the vessels of the lower thyroid gland were closed using a harmonic scalpel (Fig. 1C). The entry point of the RLN was located, the gland was partially separated from the surface of the trachea, and the thyroid isthmus was incised using an ultrasonic knife (Fig. 1D). The resected specimen was extracted through an axillary incision. Central lymph nodes were dissected, meticulous haemostasis was achieved, and the axillary incision was closed after leaving a closed suction drain in place.

Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy: transaxillary approach. (a) Incision design. (b) Workspace for thyroidectomy. (c) RLN dissection. (d) After thyroidectomy. CH-SCM, clavicular head of sternocleidomastoid muscle; SH-SCM, sternal head of sternocleidomastoid muscle; IJV, internal jugular vein; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Surgical procedure for GETTSA

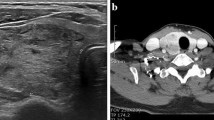

The surgical technique for GETTSA has been previously described in detail11. The patient was placed in the supine position under general anaesthesia, and the head was tilted to the other side of the operation. After making a 5-cm incision along the skin line below the midpoint of the clavicle (Fig. 2A), the skin and subcutaneous tissue were incised, and a flap was created along the clavicular head of the SCM, bounded superiorly by the hyoid level of the SCM, inferiorly by the clavicle, laterally by the external edge of the SCM, and medially by the internal edge of the SCM. Furthermore, by separating the sternal head of the SCM from the clavicular head in an upward and downward direction, a specialized endoscopic retractor was inserted to lift the sternal head. The endoscope was introduced, and the sternal head of the SCM was lifted to expose and free the scapulohyoid muscle. Additionally, the strap muscles were elevated using an endoscopic atraumatic forceps, and a combination of an ultrasonic scalpel and endoscopic dissector was alternately used to carefully separate the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia between the strap muscles and the carotid sheath.Adjusted the retractor to further elevate the strap muscles, and the thyroid bed reached the space between the clavicular and sternal heads of the SCM and across the carotid sheath (Fig. 2B). Using an ultrasonic knife, the carotid artery was dissected along its medial border, specifically at the level where it lies adjacent to the prevertebral fascia and oesophagus. The RLN and inferior parathyroid glands were explored and protected (Fig. 2C). After clamping and disconnecting the inferior thyroid artery, the thyroid glands were retracted contralaterally, exposing their dorsal side, the RLN was found entering the larynx, and the parathyroid glands were detached. The superior pole of the thyroid gland was pulled downwards, exposing the vessels, which were clamped and severed. The thyroid gland was separated from the trachea, and the thyroid isthmus was incised using an ultrasonic knife (Fig. 2D). The specimens were removed, examined for parathyroid glands, and subjected to rapid intraoperative pathological examination. The central lymph node was removed after intraoperative confirmation of PTC. Finally, the wound was flushed with endoluminal suction to check for active bleeding and closed sequentially.

Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy: transsubclavian approach. (a) Incision design. (b) Workspace for thyroidectomy. (c) RLN dissection. (d) After thyroidectomy. CH-SCM, clavicular head of sternocleidomastoid muscle; SH-SCM, sternal head of sternocleidomastoid muscle; IJV, internal jugular vein; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Observation indicators

Data were collected from the patient’s medical records, and a database was established to record the surgical approach, tumour location, patient age and sex, body mass index (BMI), presence of hypertension, coronary artery atherosclerotic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, maximum tumour diameter, thyroid capsule invasion, operative duration, postoperative hospital stay, hospitalisation costs, and drainage volume on the first postoperative day. We assessed the surgical safety of each operative approach by recording the parathyroid autotransplantation results, evaluating RLN palsy, and assessing other complications. Additionally, we measured the total number of retrieved central lymph nodes, the number of metastatic central lymph nodes, and surgical completeness.

Statistical analyses

Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to minimise patient selection bias and adjust for differences in baseline clinical characteristics. The propensity scores of the individuals were calculated using logistic regression analysis (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS] version 27.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For PSM, 10 clinical factors potentially influencing surgical outcomes were selected as covariates: tumour location, age, sex, BMI, presence of hypertension, coronary artery atherosclerotic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, maximum tumour diameter, and thyroid capsule invasion. After including all the aforementioned variables, we performed a 1:1 PSM using the nearest-neighbour method with a calliper width of 0.06 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.

Data were analysed using the independent-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test using SPSS software (version 27.0). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University (No. 2024 − 168). Informed consent from participants was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

During the study period, 351 eligible patients underwent radical surgery for unilateral thyroid cancer involving unilateral thyroid lobectomy, isthmus resection, and central cervical lymph node dissection. Among these patients, 98 opted for GETTA, and 253 opted for GETTSA. After PSM, 196 patients (n = 98 [GETTA group]; n = 98 [GETTSA group]) remained in the study population (Fig. 3), and the two matched groups were well-balanced regarding the 10 covariates. No significant statistical differences were observed between the two groups in terms of tumour location (P = 0.567), age (GETTA, 35.50 [32.00–43.00] vs. GETTSA, 37.50 [33.00–44.00] years, P = 0.157), sex (P = 1.000), presence of comorbid hypertension (P = 0.155), presence of comorbid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (P = 0.371), tumour size (GETTA, 0.60 [0.50–0.80] vs. GETTSA, 0.70 [0.50–0.93] cm, P = 0.741), and invasion of the thyroid capsule (P = 0.886). No patient had a history of coronary heart disease or diabetes mellitus (Table 1).

Surgical characteristics, hospital stays, and hospitalisation cost

The operative duration in the GETTA group was significantly longer than that in the GETTSA group (120.00 [103.75–140.00] vs. 110.00 [90.00–125.00] min, P = 0.001). The postoperative hospital stay in the GETTA group was longer than that in the GETTSA group (1.00 [1.00–3.00] vs. 1.00 [1.00–2.00] days, P = 0.008). Additionally, hospitalisation costs in the GETTA group were significantly higher than those in the GETTSA group (23,973.02 [22,640.80–25,379.80] vs. 23,306.00 [21,968.97–24,070.68] yuan, P = 0.015). The postoperative drainage volume in the GETTA group was significantly greater than that in the GETTSA group (60.00 [50.00–70.00] vs. 46.50 [40.00–56.25] mL, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Safety assessment

No significant differences were observed in the rates of intraoperative parathyroid autotransplantation (10.2% vs. 6.1%, P = 0.297) or vocal cord paralysis (1.0% vs. 3.1%, P = 0.613) between the GETTA and GETTSA groups (Table 3). None of the patients experienced postoperative complications, such as hypoparathyroidism, postoperative haemorrhage, seroma or surgical site infection, Horner’s syndrome, or celiac fistula.

Efficacy of central neck dissection in the two procedures

Fewer lymph nodes were cleared by central lymph node dissection in patients in the GETTA group compared to those in the GETTSA group (4.00 [2.00–7.00] vs. 5.00 [3.00–8.00], P = 0.036), but the number of metastases of central lymph nodes between the two groups was not significantly different (0.00 [0.00–1.00] vs. 0.00 [0.00–1.00], P = 0.645) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study compared the surgical characteristics, postoperative hospital stay, hospitalisation costs, safety, and completeness of the procedure between the GETTSA and GETTA groups of patients undergoing radical thyroid cancer surgery. PSM was used to minimise patient selection bias and differences in confounders in multiple analyses. The baseline clinical characteristics, including tumour location, sex, age, comorbid hypertension, comorbid coronary artery disease, comorbid diabetes mellitus, comorbid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, maximum tumour diameter, and thyroid capsule invasion, were consistent between the two groups.

This study included patients who were diagnosed with thyroid cancer based on postoperative pathological confirmation and underwent preoperative fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the thyroid. The Bethesda system was used to interpret FNAB cytology results. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (BSRTC) classifies thyroid cytology reports into six categories: non-diagnostic or unsatisfactory specimen (I), benign lesion (II), atypia of undetermined significance (AUS) or follicular lesion of undetermined significance (FLUS) (III), follicular neoplasm or suspicious for a follicular neoplasm (IV), suspicious for malignancy (V), and malignant (VI). The patients in our study had preoperative FNAB results classified as Bethesda VI, and their postoperative pathological findings confirmed malignant tumors. However, at our institution, there were cases where preoperative FNAB results were Bethesda II-V, but the postoperative pathology revealed malignant tumors. These cases were considered “incidental”, as thyroid cancer was diagnosed by a pathological study of the surgical specimen, with no previous suspicion by other diagnostic methods before surgery. We did not conduct a detailed statistical analysis for these patients, but Mulita et al. reported that 1.53% (8/522) of Bethesda II cases had incidental malignancies detected upon comparison of FNAB results with final pathological findings12. Rodrigues et al. expanded this finding, showing that when comparing the FNAB results with the entire surgical specimen pathology, the incidence of incidental cancer increased to 9%, with even higher rates in Bethesda III (17.5%) and Bethesda IV (19%) cases13. These findings highlight the importance of performing an anatomical pathological examination of the entire surgical specimen, not just the macroscopically visible lesions. Ultrasound-guided FNAB is an excellent method for the clinical assessment of thyroid nodules; however, careful selection of the biopsy site is crucial.

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) published treatment guidelines for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC)14, suggesting lobectomy only for low-risk patients with thyroid cancer size less than 1 cm. Total thyroidectomy is recommended when the primary thyroid carcinoma is > 4 cm, if there is extrathyroidal invasion, or if regional or distant metastases are clinically present. For tumors that are between 1 and 4 cm in size, either a bilateral or a unilateral thyroidectomy may be suitable as treatment plan. Older age (> 45 years), contralateral thyroid nodules, a personal history of radiation therapy to the head and neck, and familial DTC may be criteria for recommending a bilateral procedure. In our study, all included patients had unilateral PTC with tumor size < 4 cm and underwent unilateral thyroidectomy. For patients with tumors > 4 cm, we typically choose total thyroidectomy over subtotal thyroidectomy. Subtotal thyroidectomy is the procedure in which a remnant of the thyroid is left at the tracheal attachments while the rest of the gland is removed. This procedure is suitable for multinodular goiter and some cases of hyperthyroidism. Compared with subtotal thyroidectomy, total thyroidectomy offers a lower risk of local recurrence and neck lymph node metastasis15, and does not significantly increase the risk of early postoperative complications, such as bleeding, recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) paralysis, or postoperative hypocalcemia16. It could be also considered in patients with indeterminate nodules with bilateral nodular disease and want to avoid a completion thyroidectomy if the indeterminate nodule is malignant, significant comorbidities and a history of childhood neck radiation or familial thyroid cancer, because the risk of cancer in the remaining thyroid tissue is higher. It is also proposed as the initial surgery when there is a high risk of aggressive disease and local recurrence, such as when nodules have radiologic evidence of extrathyroidal extension (ETE) or the adjacent structures are invaded.

From a surgical access perspective, GETTA and GETTSA have advantages and disadvantages. Both approaches can achieve good cosmetic results and are used in lateral approach surgery. They effectively circumvent the linea alba cervicalis, minimising damage to the anterior cervical musculature and subcutaneous nerves, thereby reducing postoperative dysphagia17,18. Furthermore, GETTA has gradually gained acceptance among surgeons owing to its advantages of incision concealment and good postoperative swallowing function18. No significant safety differences were observed compared to conventional open thyroidectomy. Regarding cosmetic outcomes, the axillary surgical incision in the GETTA was superior to that in the GETTSA. Compared to traditional open surgery, both surgical incisions are relatively concealed and can be easily hidden by everyday clothing. However, for clothing that does not cover the clavicle, GETTA offers a distinct advantage, making it more suitable for patients with higher aesthetic demands (Fig. 4). Zhang et al. reported that GETTA resulted in a larger subcutaneous separation area, increased surgical complexity, and challenges in adequately revealing the central neck area owing to its extended operating distance and obstruction by the clavicle and sternoclavicular joints. Conversely, GETTSA, with its shorter operating distance and reduced obstruction by the clavicle and sternoclavicular joints, can diminish the extent of subcutaneous separation, decrease surgical complexity, and enhance visualisation of the central area5,19. GETTSA has the following advantages over GETTA. First, it is a more convenient surgical operation; owing to the shorter operating distance, the subcutaneous cavity is smaller, shortening the learning curve and making it easier for surgeons to master. Second, the patients experienced less discomfort in the operative area, as the flap separation range was small, and the range of postoperative skin numbness was also small. Third, it produced less trauma; with the reduced scope for cavity formation, the damage was significantly reduced18,19. However, the surgical characteristics of GETTA and GETTSA have not been analysed using statistical data analysis.

Cervical cosmetic outcome after GETTA and GETTSA. (a) The incision scar at 1 month after GETTA. (b) Surgical scar is covered. (c) The incision scar at 1 month after GETTSA. (d) Surgical scar is covered by clothes. GETTA, gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transaxillary approach; GETTSA, gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy transsubclavian approach.

The study revealed significant advantages in surgical and hospitalisation characteristics in the GETTSA group, including shorter operative duration, shorter postoperative hospital stay, lower hospitalisation costs, and reduced postoperative drainage compared to those in the GETTA group. This is because, for most surgeons, performing the same procedure in the GETTA group versus in the GETTSA group requires a longer surgical path and, therefore, more surgical time. Consequently, this results in greater cavity creation and trauma, leading to increased postoperative drainage, longer recovery times, and longer postoperative hospital stays. These findings align with those of Zhu et al., which indicated that the GETTSA group exhibits superior operative durations and cost advantages compared to the GETTA group8.

The surgical safety was evaluated based on the presence of intraoperative parathyroid autotransplantation, temporary RLN traction injury, and any other postoperative complications. No significant differences were observed between the GETTSA and GETTA groups regarding intraoperative parathyroid autotransplantation and temporary vocal cord paralysis (vocal cord paralysis returned to normal at the 3-month postoperative follow-up visit). Neither tracheal, nor oesophageal, nor laryngeal tissues were damaged in any of the groups. Since radical surgery for unilateral thyroid cancer was performed in both cases, none of the patients experienced postoperative symptoms of hypoparathyroidism, such as numbness of the hands and feet or convulsions. None of the patients in either group experienced postoperative complications such as postoperative bleeding, seroma, surgical site infection, Horner’s syndrome, or celiac fistula. Therefore, no significant difference was observed between the two groups regarding surgical safety.

Although the GETTSA group had more central neck lymph nodes cleared than the GETTA group, the number of lymph node metastases between the two groups was not significantly different. Thus, the effectiveness of central lymph node dissection was comparable in both groups.

Several limitations must be acknowledged in this study. First, the study population was derived from a single-center cohort, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The retrospective design of the study inherently introduces the risk of selection bias. Patients were not randomly assigned to treatment groups, and factors such as age, tumor characteristics, and comorbid conditions could have influenced the decision to undergo either axillary or supraclavicular approaches. Although we attempted to mitigate these biases through propensity score matching (PSM), unmeasured confounders may still exist, potentially affecting the results.

Additionally, as a retrospective study, this research relied on preoperative patient records, imaging, and pathological data, which could lead to incomplete or inconsistent documentation, as well as potential errors. For example, the surgical records, descriptions of postoperative complications, and follow-up data may have been incomplete, which could influence the accuracy of data analysis and the results. The reliance on historical data means that detailed intraoperative or postoperative information (such as intraoperative blood loss, surgical difficulty, and postoperative recovery) may not have been fully captured, potentially impacting the assessment of surgical techniques.

In the future, prospective studies and multi-center collaborations will be necessary to further validate the reliability and generalizability of these findings. Moreover, in prospective studies, we plan to meticulously record and control for factors that may influence the outcomes of different surgical approaches, and conduct related analyses to minimize the impact of these biases. This will help to provide a more robust understanding of the comparative effectiveness of different surgical approaches in the treatment of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Conclusions

This study indicates that GETTA and GETTSA can be safely and completely performed during radical thyroid cancer surgery. GETTA and GETTSA have inherent advantages. GETTA offers superior cosmetic results, whereas GETTSA boasts shorter operative durations, shorter hospital stays, and lower hospitalisation costs, making it a more clinically valuable option. This study offers additional criteria for guiding patients and surgeons in choosing between GETTA and GETTSA. Nevertheless, studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to examine tumour recurrence after GETTA and GETTSA.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from publicly available and freely accessible database (Science Data Bank, https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.12704).

References

Kurumety, S. K. et al. Post-thyroidectomy neck appearance and impact on quality of life in thyroid cancer survivors. Surgery 165, 1217–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.03.006 (2019).

Lu, Q., Zhu, X., Wang, P., Xue, S. & Chen, G. Comparisons of different approaches and incisions of thyroid surgery and selection strategy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1166820. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1166820 (2023).

Choi, Y. et al. Impact of postthyroidectomy scar on the quality of life of thyroid cancer patients. Ann. Dermatol. 26, 693–699. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.693 (2014).

Shimizu, K., Akira, S. & Tanaka, S. Video-assisted neck surgery: endoscopic resection of benign thyroid tumor aiming at scarless surgery on the neck. J. Surg. Oncol. 69, 178–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199811)69:3<178::aid-jso11>3.0.co;2-9 (1998).

Zhang, D. G. et al. Modified gasless trans-subclavian approach endoscopic lateral neck dissection for treatment of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a series of 31 cases. Chin. J. Surg. 61, 801–806. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112139-20221201-00509 (2023).

Yoon, J. H., Park, C. H. & Chung, W. Y. Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy via an axillary approach: experience of 30 cases. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc Percutan Tech. 16, 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1097/00129689-200608000-00006 (2006).

Zheng, C. M., Mao, X. C., Wang, J. F., Tan, Z. & Ge, M. H. Preliminary evaluation of effect of endoscopic thyroidectomy using the gasless unilat-eral axillary approach. Chin. J. Clin. Oncol. 45, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8179.2018.01.801 (2018).

Zhu, X. M. et al. Clinical comparison of transaxillary and transsubclavian endoscopic surgery for cN0 papillary thyroid carcinoma. Chin. J. Endocr. Surg. 17, 399–403. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn.115807–20221205–00352 (2023).

Zheng, G. et al. Transoral versus gasless transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy: a comparative study. Updates Surg. 74, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01062-y (2022).

Zheng, C. M., Xu, J. J., Jiang, L. H. & Ge, M. H. Endoscopic thyroid lobectomy by a gasless unilateral axillary approach: Ge & Zheng’s seven-step method. Chin. J. Gen. Surg. 28, 1336–1341. https://doi.org/10.7659/j.issn.1005-6947.2019.11.003 (2019).

Zheng, G. et al. Gasless single-incision endoscopic surgery via Subclavicular Approach for lateral Neck dissection in patients with papillary thyroid Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31, 1498–1508. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-14639-1 (2023).

Mulita, F. et al. Cancer rate of Bethesda category II thyroid nodules. Medicinski Glasnik. 19, 0–0. https://doi.org/10.17392/1413-21 (2021).

Rodrigues, M. G. et al. Incidental thyroid carcinoma: correlation between FNAB cytology and pathological examination in 1093 cases. Clinics https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2022.100022 (2022).

Haugen, B. R. et al. American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 26, 1-133 (2016). (2015). https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

Giuffrida, D. et al. Thyroidectomy as Treatment of Choice for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Int J Surg Oncol 2715260 (2019). (2019). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2715260

Bouchagier, K. et al. Thyroidectomy for the management of differentiated thyroid carcinoma and their outcome on early postoperative complications: a 6-year single-centre Retrospective Study. Chirurgia https://doi.org/10.21614/chirurgia.2736 (2022).

Lombardi, C. P. et al. Video-assisted thyroidectomy significantly reduces the risk of early postthyroidectomy voice and swallowing symptoms. World J. Surg. 32, 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-007-9443-2 (2008).

Xu, J. J. et al. Clinical application of the gasless unilateral axillary approach in endoscopic thyroid surgery. Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 55, 913–920. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn115330-20200225-00126 (2020).

He, G. F. et al. A video report of a case of gasless endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy with right central lymph node dissection by transsubclavian approach. Chin. J. Gen. Surg. 32, 1705–1712. https://doi.org/10.7659/j.issn.1005-6947.2023.11.009 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongji Wu: conceptualization, methodology, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, and investigation; Meiyu Zhu: methodology, statistical analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, and investigation; Chi Ma: writing – review and editing, validation, and investigation; Rui Yang: acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, statistical analysis; Yanzhong Gu: acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, statistical analysis; Shujian Wei: acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data; Xincheng Liu.: acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data; Haiqing Sun: writing – review and editing, validation; Guibin Zheng: writing – review and editing, validation; Xicheng Song: methodology, writing – review and editing, validation, investigation, and supervision; Haitao Zheng: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, validation, investigation, and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Zhu, M., Ma, C. et al. Transaxillary vs. Transsubclavian Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy approaches for papillary thyroid cancer. Sci Rep 15, 215 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84683-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84683-8