Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected global health system, significantly altering not only the acute management of viral infection, but also management strategies for chronic diseases. This study aimed to investigate the impact of COVID-19 infection on exacerbation rates and the economic burden in patients with COPD. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the national insurance reimbursement data of South Korea. Eligible participants included COPD patients diagnosed with COVID-19 between January and December 2020. We analyzed exacerbation rates, healthcare utilization, and medical costs pre- and post-COVID-19 infection. In 3,445 COPD patients who were infected by COVID-19, COVID-19 infection resulted in increased annual moderate-to-severe and severe exacerbations compared to pre-COVID-19 infection (IRR = 1.062 [95%CI 1.027–1.099]; IRR = 1.315 [95%CI 1.182–1.481], respectively). Among previously non-exacerbators, 11.2% of patients transitioned to exacerbator after COVID-19 infection. Older age, comorbidities and use of triple therapy were the factors associated with transitioners. Direct medical costs escalated significantly from approximately $6810 to $11,032, reflecting the increased intensity of care after COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 infection has significantly increased rate of exacerbations in patients with COPD and imposed a heavier economic burden on healthcare system. Among non-exacerbators, substantial number of patients transitioned to exacerbators after COVID-19 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented challenges and changes across the world, fundamentally altering the context of global health1. In South Korea, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported on January 20, 20202. Following this, strict public health interventions, such as mandatory mask usage and social distancing, were implemented to control the spread of the virus3. By May 19, 2024, the total number of confirmed cases worldwide had reached 775,522,404, with 7,049,617 reported deaths in South Korea4. It has impacted every aspect of healthcare, notably influencing the acute management of the viral infection itself, from detection and diagnosis to treatment protocols5-7. Beyond these immediate effects, the pandemic has also profoundly influenced the management and trajectory of chronic diseases, posing challenges to ongoing management strategies for these conditions8−10.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a prevalent and progressive respiratory disease, is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction, primarily caused by long-term exposure to noxious particles or gases11. Exacerbation, defined as a sudden worsening of symptoms such as increased breathlessness, cough, and sputum production, has been reported to lead to the acceleration of lung function decline, deterioration of quality-of-life, more frequent exacerbation, and increased mortality12. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the exacerbation rate of COPD has been reported to be lower, attributed largely to protective measures implemented by governments, such as widespread mask mandates, social distancing, and increased public awareness of respiratory hygiene13−16.

One of the most important factors for future exacerbation is the previous exacerbation history11,12. Frequent exacerbators are shown to be characterized by increased inflammation, a higher number of comorbidities, and poorer baseline lung function12,17−19. The status between frequent and non-frequent exacerbators may change due to variations in treatment adherence, environmental factors, or newly developed comorbid conditions20−23. Limited studies have shown the impact of COVID-19 infection on the exacerbation rate between pre- and post-infection in patients with COPD.

In this study, we aimed to identify the different rates of exacerbation frequency between pre- and post-COVID infection in patients with COPD. We hypothesized that those who have infected with COVID-19 may become more frequent exacerbators. Moreover, we aimed to analyze the difference in characteristics between non-exacerbators and exacerbators in post-COVID-19 patients with COPD, among pre-COVID-19 non-exacerbators.

Methods

Study population and data collection

The HIRA database, which encompasses insurance reimbursement claims from all medical centers in South Korea, provides detailed information including patient demographics, types of medical centers, diagnoses (using the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; ICD-10 classification), prescribed medications, and medical costs24. For this research, we selected patients with COVID-19 infection and COPD from January to December 2020. COVID-19 infection was detected with the presence of ICD-10 codes of U071, U072, U09, and U099. COPD patients were identified based on the following criteria: age 40 years or older; a primary or secondary (within the fourth position) diagnosis of COPD according to ICD-10 codes J43-J44 (excluding J43.0); and receipt of COPD medications (such as systemic β2-agonists, theophylline, LABA, LAMA, combinations of LABA and LAMA, SABA, SAMA, combinations of SABA and SAMA, ICS combined with LABA, or PDE4 inhibitors) at least twice a year throughout the duration of the study, as previously described25−27. To evaluate clinical characteristics and medical costs in pre- and post-COVID-19 infection, we extracted data from January 2019 to December 2021. The pre-COVID period was defined as 1 year before the registered COVID-19 infection date for each patient, and the post-COVID period was defined as 1 year after the infection date. We excluded patients who had re-infection of COVID-19 within a year.

Clinical parameters

General characteristics including age, sex, insurance type (national health insurance, medical aid, veterans’ insurance), and comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, malignancy, and renal insufficiency were collected from the database. Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (mCCI) was calculated according to a previously described method. Information on types of COPD medication was gathered including long-acting beta agonist (LABA) or long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), LABA plus LAMA, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus LABA, and ICS plus LABA plus LAMA were collected.

Exacerbation

The operational definition of a moderate exacerbation encompasses the following criteria: an outpatient visit, a diagnosis of COPD as indicated by ICD-10 codes J43–J44 (excluding J43.0), and the prescription of antibiotics or systemic corticosteroids. A severe exacerbation is defined by an emergency room visit or hospital admission with presence of ICD-10 code for COPD, and the prescription of antibiotics and/or systemic corticosteroids. Patients with ICD-10 codes for pneumonia (J12–J17), pulmonary embolism (I26, I26.0, or I26.9), or acute respiratory distress syndrome (J80) were excluded. If events occur within a 14-day period, they are considered a single exacerbation event. All the operational definitions for exacerbations were previously described26,27.

Exacerbators are defined by those with ≥ 2 moderate exacerbation or ≥ 1 severe exacerbation in 1 year, whereas non-exacerbators are defined by those with no exacerbation or 1 moderate exacerbation in 1 year.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide (version 7.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Categorical variables are presented as numbers (%) and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The differences in the percentage of patients who experienced exacerbations and in medication use between the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods were compared using McNemar’s test. Difference of annual exacerbation rate between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 period in patients with COPD were analyzed with binomial mixed model. The differences in 1-year direct medical costs between the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods were compared overall, by post-COVID-19 exacerbation status, and by type of medical use (inpatient and outpatient), using paired t-tests. Also, we compared differences of baseline characteristics between non-exacerbators and exacerbators in post-COVID-19 patients, among pre-COVID-19 non-exacerbators. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Student’s t-test and categorical variables with the χ2 test.

Results

General characteristics of study subjects

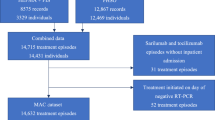

Among 83,123 patients with COVID-19 infection in 2020, number of eligible COPD patients without re-infection event of COVID-19 within year was 3,445 (Fig. 1). Mean age of the population was 70.42 ± 1.44, and 70.1% were male (Table 1). Most of the patients were covered by NHI, and mean mCCI was 6.07 ± 3.18.

Differences of annual exacerbation rate before and after COVID-19

Compared to pre-COVID-19 period, post-COVID-19 period showed increase in the proportion of patients experiencing moderate-to-severe (26.5% vs. 34.2%, respectively) and severe (7.31% vs. 9.6%, respectively) exacerbation (Table 2). In binomial mixed model, incidence rate ratio (IRR) of moderate-to-severe exacerbation between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 period was 1.062 (95%CI, 1.027–1.099; p < 0.001), and severe exacerbation was 1.315 (95%CI 1.182–1.481, p < 0.001) (Table 3, Figure S1), suggesting more frequent moderate-to-severe and severe exacerbation shown in post-COVID-19 compared to pre-COVID-19 infection.

Differences in baseline characteristics between non-exacerbators and exacerbators in post-COVID-19 patients, among pre-COVID-19 non-exacerbators

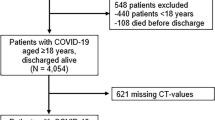

The number of exacerbators increased from 454 to 499 patients before and after COVID-19 infection, respectively (Fig. 2). Among the 2,991 patients who were non-exacerbators before COVID-19 infection, 334 (11.2%) patients transitioned to exacerbators. Those who transitioned to exacerbators showed older age, and more covered by medical aid or veterans’ insurance. Use of triple therapy (ICS + LABA + LAMA) at baseline were more frequent in those who transitioned to exacerbators compared to consistent non-exacerbators (Table 4).

Difference of medical usage between pre- and post-COVID-19 infection

The usage of LABA plus LAMA medications for COPD increased from 7.0 to 8.5% (p < 0.003), while there was no significant difference in use of mono-bronchodilator and triple therapy (Table 2). The total direct medical costs increased from the pre-COVID-19 to the post-COVID-19 period, from $6809.95 ± 11521.08 to $11032.19 ± 18834.31 (Exchange currency: 1 USD = 1366.00 KRW [based on 29 May 2024], p < 0.001) (Table 5). The increased costs were comparable whether individuals were non-exacerbators or exacerbators in the post-COVID-19 period.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 infection on the exacerbation rates of COPD patients, alongside variations in medication use, and direct medical costs before and after COVID-19. Our findings revealed a significant increase in the proportion of patients experiencing moderate-to-severe and severe exacerbation after COVID-19 infection, with exacerbation becoming more frequent compared to the pre-COVID-19 year. This escalation is paralleled by increase in the utilization of LABA + LAMA combination therapy, suggesting a shift towards more aggressive management strategies during the pandemic. Among patients who were non-exacerbators before COVID-19 infection, 27.0% of patients transitioned to frequent exacerbators; those with older age, more comorbidities and using triple therapy at baseline were more likely to be the transitioners. Lastly, the economic analysis further revealed a significant rise in the direct medical costs after COVID-19 infection, reflecting the elevated healthcare demands and the intensified treatment regimens required for managing patients.

The increased risk of exacerbation in patients with COPD following COVID-19 infection indicates significant immunological and pathologic mechanisms28,29,30. Viral infections are known to be a prominent trigger for exacerbation in COPD, and SARS-CoV-2 contributes to this by inducing extensive lung inflammation and tissue damage28,30. Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 aggravates airway inflammation in COPD patients, potentially due to the virus’s interaction with ACE2 receptors, which are highly expressed in the lung tissue28,31. This interaction not only facilitates viral entry but also exacerbates the inflammatory response, which can worsen respiratory symptoms and precipitate exacerbation. Immunologically, the systemic inflammatory response to COVID-19, often resulting in cytokine storm, is particularly detrimental for COPD patients, as it can lead to an exaggerated immune response, further impairing lung function32,33,34. Dysregulation in immune response due to COVID-9 could lead to increased susceptibility to severe exacerbation in patients with COPD35.

As a result of the immunological and pathological mechanisms triggered by COVID-19, our study observed a considerable transition from non-exacerbators to exacerbators among COPD patients after COVID-19 infection. Frequent exacerbator is known to be one of the phenotypes in COPD, which has been shown to be associated with more COPD symptoms, increased lung function decline rate and mortality12,17−19. As our study showed that factors such as older age, the presence of comorbidities, and the use of triple therapy at baseline were identified as key predictors of transition into frequent exacerbators, it is crucial to implement targeted monitoring and tailored interventions for these high-risk patients.

The economic burden of the COVID-19 pandemic was massive, with a global mortality cost of $3.5 trillion being imposed36. As largely of preventive measures, the exacerbation rates of COPD have been shown to be lowered during COVID-19 pandemic13−16. However, our study has shown that the economic burden of COVID-19 infection on individuals with COPD has elevated, primarily due to increased exacerbation rates and the corresponding need for step-up treatment. This burden may also compounded by higher health-care resource utilization among COPD patients, including increased rates of hospitalization, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation, resulting in higher mortality compared to non-COPD patients, which have presented in the previous studies37,38,39. Therefore, COVID-19 infection in patients with COPD not only demand immediate medical attention but also lead to prolonged recovery periods, increasing the overall healthcare cost substantially.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, shielding measures such as mask mandates and social distancing were widely implemented, helping to reduce respiratory infections and exacerbations in patients with COPD3. In Korea, these protective strategies were strictly enforced starting in March 20203. These measures likely contributed to fewer viral and bacterial respiratory infections40. For example, the number of severe acute respiratory infections decreased dramatically (from 18.61 to 6.25 per 1,000 hospitalized patients) in Korea41. Despite overall decrease of respiratory infection, our study observed an increase in exacerbations among COPD patients post-COVID-19 infection. This suggests that the direct effects of COVID-19 on COPD exacerbations outweighed the protective benefits of shielding measures, resulting in higher exacerbation rates.

Our study used robust data from a comprehensive national health insurance reimbursement database, providing a significant sample size that enhances the generalizability of our findings across the COPD population. The use of longitudinal data allows for a detailed analysis of changes in exacerbation rates and medical costs before and after COVID-19 infection, offering valuable insights into the pandemic’s impact on COPD. Additionally, our data focused on the clinical impact of COVID-19 infection in individuals with COPD, an area that has not been thoroughly studied.

However, there are some limitations in this study. First, this study has limitation for the nature of the observational study, which has limitation to establish causality between COVID-19 and exacerbation rates. Potential confounders including differences in healthcare accessibility, diagnostic accuracy, and patients’ compliance with treatment might have influenced the outcomes. Second, there are potential underreporting of COPD exacerbations if patients avoided hospital visits during the pandemic era, leading to data that might not fully capture the incidence of exacerbations. Third, the reliance on reimbursement data may overlook detailed clinical features, which are not captured in the system, including severity of symptoms, lung function, and exact reasons for changes in medication regimens. Fourth, since patient inclusion in this study relied on insurance reimbursement claims for a COVID-19 diagnosis, there is a risk that mild cases may have been under-reported. Some patients with mild symptoms may have self-managed or not sought medical care, leading to missed diagnoses, particularly with rapid antigen tests (RAT). Additionally, some individuals with self-reported positive RAT results and mild symptoms may not have sought medical treatment or insurance reimbursement, contributing to the potential under-diagnosis of COVID-19 in our cohort. This could have resulted in an underestimation of the true prevalence of COVID-19 within the study population. Fifth, the use of insurance claim data limits our ability to determine whether patients with malignancies were in an active state or receiving treatment. This lack of detailed clinical information restricts our capacity to evaluate the impact of malignancy status on immune function and susceptibility to infections, including COVID-19. Lastly, changes in the prescription of inhalers before and after the COVID-19 pandemic may not necessarily be attributed solely to the patients’ conditions or the impact of COVID-19; individual doctors’ prescribing patterns could have also influenced the use of these medications.

In conclusion, this study highlights the increased risk of exacerbation in patients with COPD and the subsequent escalation of medical costs following COVID-19 infection. We have identified notable increase in the proportion of those who experienced exacerbation between 1-year pre- and post-COVID-19, and in the frequency of exacerbations. Furthermore, among non-exacerbators in pre-COVID-19 period, considerable number of patients transitioned to exacerbators after COVID-19 infection. These findings show profound impact of COVID-19 on individuals with COPD, emphasizing the need for heightened surveillance for the vulnerable population. Furthermore, the increased economic burden due to higher healthcare demands also shows importance of integrating cost-effective approaches of these patients. It is crucial for the future research to further explore the long-term impact of COVID-19 on COPD patients and to adjust clinical practices accordingly to enhance patients’ outcomes in post-pandemic healthcare settings.

Data availability

The datasets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Assefa, Y. et al. Reimagining global health systems for the 21st century: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health 6, e004882 (2021).

Apio, C., Han, K., Lee, D., Lee, B. & Park, T. Development of New Stringency Indices for Nonpharmacological Social Distancing policies implemented in Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic: Random Forest Approach. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 10, e47099 (2024).

Arora, A. S., Rajput, H. & Changotra, R. Current perspective of COVID-19 spread across South Korea: exploratory data analysis and containment of the pandemic. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 6553–6563 (2021).

Alhazzani, W. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines on the management of adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: first update. Crit. Care Med. 49, e219–e234 (2021).

Yuan, Y., Jiao, B., Qu, L., Yang, D. & Liu, R. The development of COVID-19 treatment. Front. Immunol. 14, 1125246 (2023).

Sharma, A., Ahmad Farouk, I. & Lal, S. K. COVID-19: a review on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Evolution, Transmission, Detection, Control and Prevention. Viruses 13, 202 (2021).

Tiotiu, A. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management of chronic noninfectious respiratory diseases. Expert Rev. Respir Med. 15, 1035–1048 (2021).

Oseran, A. S. et al. Long term risk of death and readmission after hospital admission with covid-19 among older adults: retrospective cohort study. Bmj 382, e076222 (2023).

Castanares-Zapatero, D. et al. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 54, 1473–1487 (2022).

Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung. Disease (GOLD) guidelines, global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease (2024). https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-reports/ (.

MacLeod, M. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation fundamentals: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and disease impact. Respirology 26, 532–551 (2021).

Ho, T. et al. Examining the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on community virus prevalence and healthcare utilisation reveals that peaks in asthma, COPD and respiratory tract infection occur with the re-emergence of rhino/enterovirus. Thorax 78, 1248–1253 (2023).

Principi, N., Autore, G., Ramundo, G. & Esposito, S. Epidemiology of respiratory infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses 15, 1160 (2023).

Chu, D. K. et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 395, 1973–1987 (2020).

Poucineau, J. et al. Hospital admissions and mortality for acute exacerbations of COPD during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide study in France. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 995016 (2022).

Zhu, D. et al. Identification of frequent acute exacerbations phenotype in COPD patients based on imaging and clinical characteristics. Respir Med. 209, 107150 (2023).

McGarvey, L. et al. Characterisation of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in COPD patients in a large UK primary care population. Respir Med. 109, 228–237 (2015).

Wu, Y. K. et al. Characterization Associated with the frequent severe Exacerbator phenotype in COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 16, 2475–2485 (2021).

Lenferink, A. et al. Self-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, Cd011682 (2017).

Tian, L. et al. Ambient carbon monoxide and the risk of hospitalization due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180, 1159–1167 (2014).

Nguyen, T. C. et al. Identification of modifiable risk factors of exacerbations Chronic Respiratory diseases with airways obstruction, in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 11088 (2022).

Smith, M. C. & Wrobel, J. P. Epidemiology and clinical impact of major comorbidities in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 9, 871–888 (2014).

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Services. https://www.hira.or.kr/eng/main.do (.

Kim, E. K. et al. Cardiovascular events according to Inhaler Therapy and comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 19, 243–254 (2024).

Choi, J. Y., Park, Y. B., An, T. J., Yoo, K. H. & Rhee, C. K. Effect of Broncho-Vaxom (OM-85) on the frequency of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations. BMC Pulm Med. 23, 378 (2023).

Choi, J. Y. et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation is Associated with decreased exacerbation and mortality in patients with COPD: a nationwide Korean study. Chest 165, 313–322 (2024).

Ki, M. Epidemiologic characteristics of early cases with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease in Korea. Epidemiol. Health. 42, e2020007 (2020).

Awatade, N. T. et al. The Complex Association between COPD and COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 12, 3791 (2023).

Miura, Y., Ohkubo, H., Nakano, A., Bourke, J. E. & Kanazawa, S. Pathophysiological conditions induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection reduce ACE2 expression in the lung. Front. Immunol. 13, 1028613 (2022).

Johansen, M. D. et al. Increased SARS-CoV-2 infection, protease, and inflammatory responses in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Primary Bronchial epithelial cells defined with single-cell RNA sequencing. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 206, 712–729 (2022).

Leung, J. M. et al. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur. Respir J. 55, 2000688 (2020).

Zhang, H. P. et al. Recent developments in the immunopathology of COVID-19. Allergy 78, 369–388 (2023).

Singh, S. J. et al. Respiratory sequelae of COVID-19: pulmonary and extrapulmonary origins, and approaches to clinical care and rehabilitation. Lancet Respir Med. 11, 709–725 (2023).

de la Rica, R., Borges, M. & Gonzalez-Freire, M. COVID-19: in the Eye of the Cytokine Storm. Front. Immunol. 11, 558898 (2020).

Olloquequi, J. COVID-19 susceptibility in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 50, e13382 (2020).

Richards, F. et al. Economic Burden of COVID-19: a systematic review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 14, 293–307 (2022).

Halpin, D. M. G. et al. Healthcare Resource Utilization, and mortality of Asthma and COPD in COVID-19: a systematic literature review and Meta-analyses. J. Asthma Allergy. 15, 811–825 (2022). Epidemiology.

Poucineau, J. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on COPD Patient Mortality: a nationwide study in France. Int. J. Public. Health. 69, 1606617 (2024).

Pappe, E. et al. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Hospital Admissions, Health Status, and behavioral changes of patients with COPD. Chronic Obstr. Pulm Dis. 10, 211–223 (2023).

Cookson, W., Moffatt, M., Rapeport, G. & Quint, J. A pandemic lesson for Global Lung diseases: exacerbations are preventable. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 205, 1271–1280 (2022).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Nationwide Social Distancing and the epidemiology of severe Acute Respiratory infections. Yonsei Med. J. 62, 954–957 (2021).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: 1711179395, RS-2022-00141508).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CJY and CKR contributed to study concept/study design. KKJ contributed to data acquisition and analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation for the work. CJY and CKR contributed to drafting the work. All authors contributed to critical revision for relevant intellectual content and final approval of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital with registration number KC22ZISI0379. Informed consent from patients was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, J.Y., Kim, K.J. & Rhee, C.K. Change in exacerbation rate of COPD patients before and after COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep 15, 2427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86426-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86426-9