Abstract

This paper undertakes a multi-dimensional exploration of the glass imitation jade culture under the context of the ancient Silk Road, tracing the historical trajectory of glass manufacturing technology from West Asia to China, especially after the Han Dynasty, when the flourishing trade along the Silk Road facilitated the integration of foreign glass craftsmanship with China’s indigenous imitation jade tradition. This integration prompted Chinese glass artifacts to not only incorporate foreign techniques but also emphasize the texture and cultural symbolism of jade. Through systematic archaeological excavations and historical text analysis, this study delves into the unique phenomenon of glass imitation jade on the ancient Silk Road in China, providing detailed exposition on the formation, characteristics, and profound impact of this cultural practice. Imitation jade culture extends beyond physical forms, permeating material selection, technological innovation, and cultural symbol inheritance. As a gem of ancient Chinese craft art, the glass imitation jade culture offers valuable insights into understanding the aesthetic features of ancient cultures, cultural exchange patterns, and the evolution of craft technologies. This paper innovatively proposes that ancient glass-making practices imitation jade can serve as a new means to actively protect natural jade resources in modern times, offering a fresh perspective for the exploration and study of the Silk Road cultural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glass is one of the earliest man-made materials invented by human beings, originating in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley in the 23th and 25rd centuries BCE, with a history of more than 4000 years1. Most people’s inherent cognition of glass is that glass is regarded as a modern material. In modern life, glass has long been an easy-to-obtain material for people’s daily use, but glass was once one of the most expensive materials in history2. Around the 5th century BCE, the Book of Job in the Old Testament mentions that “gold and glass cannot be compared with wisdom”, indicating that glass and gold were of equal value at that time3,4. By the early 20th century BCE, glass was already highly esteemed and favored by people, frequently traded in early commercial activities5. Over the next 2500 years, glass beads, glassware, glass ornaments, and glass Buddhist ritual vessels, along with the art of glassmaking, traveled into China via the Silk Road and were cherished by the Chinese noble class6.

Literature review

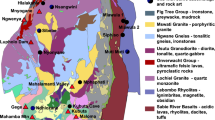

The term “Silk Road” was coined by Ferdinand von Richthofen in the late 19th century7,8. It symbolizes the major arteries that connected the political, economic, cultural, and technological exchanges between Europe and Asia, playing a crucial role in ancient international relations. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization identifies several routes of the Silk Road9,10,11: (1) the northern (grassland) Silk Road7, (2) the northwest (desert) Silk Road12 (3) the southwest (Buddhism) Silk Road13, (4) the southern (maritime) Silk Road14, as shown in Fig. 1.

The artifacts unearthed along the Silk Road reveal the trade and cultural exchanges between the East and West10,11. The wide variety of glass products unearthed along the Silk Road demonstrates the close connection and continuous communication between the development of ancient Chinese glassmaking techniques and those of the West15. Among the trade items, the West exported ancient glass vessels to the East, ultimately exerting a significant influence on China’s glass industry16. The art of glassmaking originated from the Mediterranean coast of Europe and extended through the hinterland of China to the Korean Peninsula and Japan17. In China, glassmaking began with slow progress during the pre-Qin and Han Dynasties, experienced fusion of Eastern and Western techniques during the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, and achieved comprehensive development during the Sui, Tang, Song and Yuan Dynasties, ultimately flourishing in the Ming and Qing Dynasties18. Representative glass vessels from different dynasties are depicted in Fig. 2.

Due to the lack of national cultural motivations, glassmaking has been developing slowly and has always been outside the mainstream of the development of Chinese traditional craftsmanship cultural evolution19. The idea that the glass material were mainly used to imitate jade is deeply rooted in ancient China20. The concept of imitation jade has continued from the Warring States period to the Qing Dynasty. Whether it is the lack of jade during the Song and Ming dynasties, or the relatively abundant jade materials during the Qing dynasty, imitation jade is the main purpose of glass manufacturing21. In ancient China, the most remarkable artistic achievements were consistently utilized for sacrificial purposes. The variety of glass used for sacrifices was extensive and yielded impressive results22. Glass appears as a substitute for jade, with its shape and texture imitating the appearance of jade. However, glass is not typically considered as an independent process category for application and development23. From the perspective of contemporary researchers, the emulation of jade through glass can be considered as a distinctive artistic expression in glass craftsmanship. However, throughout history, the concept of imitation not only constrained the applications of glass but also impeded its technological advancement24.

The history of glassmaking in Europe predates that in China by a significant margin. Glass trade existed in the Xinjiang region of China before the opening of the Silk Road. Glass artifacts unearthed from the Kizil tombs in Xinjiang are the earliest known in China, with their composition closely resembling ancient Western Asian glass. These artifacts date back to the Western Zhou to early Spring and Autumn periods. When the Silk Road was opened during the Han dynasty, it coincided with the flourishing period of Roman glassmaking. As early as around 1500 BCE, glassware in Egypt and Mesopotamia was already quite mature. Glass from the ancient Roman Empire was highly prized and mass-produced. At that time, the majority of glass materials were soda-lime glass, which often appeared opaque due to the combustion temperature, and was frequently used to mimic gemstones in accordance with European cultural beliefs7. This is strikingly similar to how ancient Chinese glass mimicked jade. Due to the Romans’ fondness for wine, there was a drive to enhance the visual and sensory experience of wine tasting, which accelerated the improvement of glass making techniques. This period saw the innovative invention of blown glass, which was crucial for large-scale production. From then on, glassware became both a beautiful art form and gradually established a connection with science, becoming a mainstream craft item in Europe that influenced people’s daily lives. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Sassanian and Islamic glass industries thrived in succession. After the Islamic Arabs occupied the eastern shores of the Mediterranean in the 7th century CE, the first decorative techniques that Islamic glassmakers inherited and developed were these decorative processes. In addition to producing vessels with applied threads that are hard to distinguish from Roman glass, they also produced vessels with applied decorations that are less common in Roman glass25. Glass vessels were very small used for scented oils and musk. Wine was transported in ceramic amphora. The technique of mold-blown impressed decoration was also inherited by Islamic glassmakers from their Roman Empire counterparts. Like in the Roman period, their molds were still made of clay or wood. However, Islamic mold-blown glass vessels had thicker walls and often continued to be blown without a mold after being removed from the mold, often leaving a scar from the punty on the bottom. Mold-blown glass remained popular among Islamic glassmakers for a long time, both in the early and later periods26. Cylindrical cups are a common shape in Islamic glass. During excavations in Nishapur, Iran, by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, several plain cylindrical cups dating from the 8th to 9th centuries were discovered. Round decorations are the most common applied decorations in Islamic glass, and star-shaped decorations (hexagonal, pentagonal, or triangular) are also quite popular. Engraved glass is another technique inherited by Islamic glassmakers from the Roman Empire, which was popular in the early Islamic period, although well-preserved engraved glass vessels are extremely rare. Islamic luster-painted glass is renowned worldwide, and it is generally believed that its use dates from the 12th to 15th centuries CE, with luster-painted glass from before the 9th century being very rare27. Most of the glass imported into China during the Sui, Tang, Song, and Liao dynasties via the Silk Road came from these regions, which had a significant impact on advancing the development of glass technology in China.

From the perspective of glass art history, this article explores the unique cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade” in ancient China as discussed by previous scholars28. This paper argues that “glass imitation jade” not only contributes to the sustainable development of natural resources but also to the sustainable reshaping and revival of Chinese traditional Silk Road culture in today’s modern society29. In the excavation, restoration and protection of the Silk Road heritage, it can also showcase the beauty of art and technology30.

The purpose and significance of this paper lie studying the sustainable development path of the unique cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade” during the eastward spread of glass technology along the Silk Road in China from the perspective of glass art and cross-cultural influences31. The phenomenon of “glass imitation jade” in the history of technology is considered a negative factor that hinders the development of glass. However, through the integration of sustainability concept, it provides a new and innovative academic point of view on contemporary glass technology research, mineral resources protection, artistic creation, cultural relics restoration, cultural renaissance, so that the study of ancient Chinese glass has formed a new research pattern32,33.

Research status at home and abroad

A large number of glass products unearthed along the Silk Road prove that the development of ancient Chinese glass technology has always maintained close contact with Western glass34,35,36. According to the investigation on the current state of Chinese people’s perception of glass culture, it is evident that, compared to traditional crafts such as ceramics, silk, and lacquerware, there is a general lack of fundamental understanding regarding Chinese traditional glass craftsmanship. Moreover, there is an absence of cultural identification with Chinese glass arts, with most individuals merely associating it with utilitarian purposes and contemporary daily necessities37. Internationally, especially in the studies of the history of Western glass technology, Chinese glass technology is rarely involved, and the style of Chinese glass technology along the Silk Road has been neglected38. Even during the Ming and Qing Dynasties which were the most prosperous periods for ancient Chinese glass art, it was largely excluded from global glass art studies. Academician Gan Fuxi from the Shanghai Institute of Optics and Precision Instruments, Chinese Academy of Sciences, edited and published “The Development of Ancient Glass Technology in China” in 2005 and “Research on Ancient Glass on the Silk Road” in 2007, comprehensively expounding on the developmental history of ancient Chinese glass technology, systematically summarizing and analyzing its various historical periods, and conducting systematic studies on its composition. Academician Gan’s achievements provide significant academic support for research on ancient glass. Currently, domestic research on glass on the Silk Road also focuses on the technical development and composition. Building on this foundation, further exploration into the artistic aspects and sustainability of glass technology is necessary. This includes organizing, summarizing, developing, and innovating artistic expressions and aesthetic cultural phenomena that are associated with the historical spread of glass materials eastward through China via the Silk Road39.

Currently, research on ancient Chinese glass mainly focuses on two aspects: historical philology and scientific archaeology40. The limitation of historical philology research lies in the insufficient availability of extensive ancient Chinese glass documents, resulting in a lack of corresponding correlations between unearthed cultural relics and written records. Consequently, many ancient glass objects lack accurate historical literary information41,42. Conversely, due to the absence of specific physical evidence, some information regarding certain glassware mentioned in literature can only be attributed to imagination or speculation. For example, the glazed bowl depicted in “The Glass Bowl” remains a fantasy, as no corresponding glass utensils have been found. Scientific archaeology primarily adopts a natural science perspective by conducting compositional analysis of the glass and drawing corresponding research conclusions43. For example, glassware containing lead and barium is widely recognized by scientists as a prominent representation of domestic Chinese glass and remains one of the primary methods used in global ancient glass studies. However, this approach also has limitations. First, sampling for composition analysis directly damages the valuable glass artifacts themselves, rendering many culturally significant pieces unsuitable for sampling and leaving their specific compositions unclear to date44. Second, ancient glass production is not fixed, and it is impossible to draw definitive conclusions solely based on compositional factors since human communication history spans far beyond our imagination. Both aforementioned approaches have their own merits and constraints45. Therefore, the combination of historical philology and scientific archaeology in the study has become an inevitable trend in the study of ancient Chinese glass. It has also formed a pattern of ancient Chinese glass research that today’s historical philology and scientific archaeology support each other46.

Research materials and methods

Research methods

The article explores the unique cultural phenomenon of glass craft and “glass imitation jade” in the heritage of the Chinese Silk Road from a cross-cultural perspective and its value in today’s sustainable cultural ecology47. The research method is mainly based on the comparative research method. It involves field investigations at sites where glass artifacts from the traditional Silk Road have been unearthed, consulting large number of archaeological excavation reports as evidence, and conducting museum is investigated. The research and analysis of glass cultural relics and the visits of cultural relics departments are carried out. Based on the collation and investigation of unearthed glass artifacts, it is found that the development of glass technology in the traditional Silk Road heritage has been closed and restricted by Chinese traditional cultural thoughts. Scholars at home and abroad believe that the unique cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade” has always been a negative evaluation in the study of traditional glass technology. This paper argues that absolute criticisms of the cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade” is not correct, especially in terms of sustainability48. The embodiment of sustainability is divided into two positive factors: sustainable protection of the natural environment and the sustainable development of cultural resources. Glass is a natural, safe and reliable, recyclable and extremely rich mineral resource material. Glass imitation jade not only protects the increasingly scarce jade mineral resources, but also ensures the sustainable development of the natural environment. Sustainability of cultural resources is not only the protection of Chinese jade culture, but also the unique aesthetic language of glass art developed in China through the unique artistic expression language of glass craft in a low-cost and sustainable form.

Technological development and cultural evolution of ancient glassware

The “jade culture” that originated in the early Neolithic Age is a distinctive representation of Chinese culture, setting it apart from other civilizations worldwide. Jade is revered by the Chinese as the embodiment of heavenly and earthly essence, and is imbued it with profound religious symbolism49. These jade artifacts, sourced from nature and intricately carved within imperial palaces, symbolize hierarchical status and play a crucial role in maintaining the social order through the ritual system50. Additionally, jade holds great mysterious religious significance in funerals. The appearance and color of jade are often compared to natural characteristics and moral qualities of individuals, being praised as an essential virtues for a true “gentleman”, showcasing remarkable creativity by the Chinese people. Thus, jade serves as a tangible manifestation of the Oriental spirit and forms the material foundation for China’s cultural traditions.

As the “beauty of stone” screened out by the ancestors of the Chinese nation from various stones, Chinese jade has the aesthetic qualities and practical function of warm and shining, meticulous and tough. In this long selection process, “Kunshan Jade”, that is, “Hetian Jade”, has become recognized as “Precious Jade” and “True Jade”51,52. For more than three thousand years, the texture, shape, and color of jade have inspired sculptors, painters and poets. Hundreds of schools of thought in the past dynasties interpreted Hetian jade through Confucian doctrine and endowed it with the connotation of “virtue”. Therefore, the saying that jade has eleven virtues, nine virtues and five virtues was widely spread and accepted by the whole society, becoming the spiritual pillar of Chinese jade culture. This unique jade consciousness integrates virtue in jade and compares virtue with jade, combining jade and virtue into one; at the same time, it also connects jade with gentlemen. The unique jade consciousness of the three-in-one combination of material, society and spirit is the ideological achievement of our Chinese nation and has become the rich ideological and spiritual connotation of Chinese jade culture. Chinese jade culture has a long history, rich content, wide range and far-reaching influence, which is incomparable to many other cultures. The glory of Chinese jade culture is no less than the Great Wall and the miracle of the Qin Dynasty terracotta warriors. The achievements of jade culture far exceed those of silk culture, tea culture, porcelain culture and wine culture. Jade culture contains a great national spirit, including a patriotic national spirit of “preferring jade to pieces”; the trend of “turning into jade and silk” for unity and friendship, the selfless dedication of “moistening with warmth”, the pure and honest spirit of “luster of jade cannot conceal flaws”, and the pioneering and enterprising spirit of “being sharp and resilient”53,54.

In the “jade totem” culture of the primitive Chinese society, the ancients used jade carvings with symbolic significance as the symbol of their own nation. Jade was the most respected material among the ancients and was known as the “essence of heaven and earth”. The ancients carved jade into totemic patterns such as birds and beasts. Around these totemic symbols, they also engaged in primitive public activities such as music, song and dance, reflecting that jade totem was a form of ancient culture and ideology, which contributed to the early emergence of jade culture. In ancient China, there was a high demand for jade. At that time, the mining technology was insufficient to meet this demand, resulting in extremely scarce and expensive jade raw materials that could not meet people’s needs. Glass, a synthetic material, was easily obtainable and thus came into existence. The application of ancient Chinese glass materials imitated jade. This was primarily due to the profound influence of Chinese jade culture, and the texture and appearance of lead-barium glass, crafted with the technology of the time, closely resembled jade and were therefore the most suitable materials for imitation. Consequently, glass was widely used in ancient China as a substitute for jade.

In 3500 BCE, the Mesopotamian region (present-day Iraq) discovered the earliest glass products made from raw glass materials, primarily to imitate jewelry and jade artifacts. By sixteenth century BCE, the glassmaking technology in Mesopotamia spread to Syria, Cyprus, Egypt, and the Aegean region, with the most representative examples being glass products unearthed in Egypt and Rome. Ancient Egypt produced monochrome glass beads in sixteenth century BCE, colored mosaic glass beads in tenth century BCE, and improved core-forming method in 1350 BCE. In addition to the core-forming method, the casting method was also used to mold glass into pharaoh’s heads with color stripes for decoration.

Archaeological findings indicate that the glass composition in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt was primarily sodium calcium silicate, with silica introduced from quartz sand and alkali metals from natural alkali and plant ash. The analysis of ancient Egyptian glass composition showed trace amounts of PbO and BaO, with PbO not exceeding 5% in some cases. The primary coloring agents used during this period were copper and manganese to produce different colors and transparency, rarely using cobalt55.

By the late eleventh century BCE during the Western Zhou Dynasty in China, glass began to emerge, and people gradually mastered the techniques to produce glass enameled sand beads, commonly known as dragonfly eye glass beads56. Broadly speaking, dragonfly eye glass beads are also a type of double-colored glass, shaped with two or more glass materials and decorated with dots, lines, and surfaces using other colored materials. During the Spring and Autumn Period (8th to third century BCE), the manufacturing level of enameled sand improved, with some reaching the level of glass sand. By the Warring States period, primary glass products could be produced, such as blue and light blue glass on the swords of King Fuchai of Wu and King Goujian of Yue.

The enameled sand products from Chu tombs dating to the mid to late sixth century BCE, analyzed by modern scholars, showed similar compositions to those from the Western Zhou period. Thus, it is believed that the Chu people learned the manufacturing techniques from the Zhou people and developed them, adopting various glass composition systems, including potassium calcium silicate, sodium calcium silicate, and silica-lead and silica-lead-barium systems. Coloring agents such as iron and copper produced yellow-green or blue glass. At that time, primitive porcelain and bronze ware manufacturing were both well-developed in China. Porcelain enamel was glass-like, capable of forming glass beads, and the slag from bronze smelting may have also been glass-like. These provided conditions for the development of ancient Chinese glass. The potassium calcium silicate composition of ancient Chinese glass was distinct from the sodium calcium silicate composition of ancient Western glass, while the silica-lead-barium composition was similar to bronze smelting slag, which was not found in ancient Western glass. As such, some scholars believe that these unearthed ancient glass were not introduced from the West but independently manufactured in China, known as the "indigenous theory." Besides the core-forming method, there was also the die-pressing method derived from the clay molds used in bronze casting, with molds divided into upper and lower sections. Molten glass was poured into the lower mold and pressed with the upper mold to create glass rings, sword guards, plates, and ewers.

In the tenth century BCE, glassmaking technology spread from West Asia to Greece through the Mediterranean and Crete. By the 4th to second century BCE, Greek daily glass manufacturing matured, using both the core-forming method to make glass bottles and the casting method for glass bowls. Daily glass tableware and utensils were widely used in Greece, with compositions still being sodium calcium glass containing minor amounts of potassium and magnesium, and using cobalt oxide and nickel oxide as coloring agents57.

In the fifth century BCE, Rome became the center of glass manufacturing. Around the first century CE, Roman people (some scholars believe it was the Syrians) invented the blown glass tube, creating the blowing method, which made a significant contribution to glass manufacturing technology. Romans innovated in deep processing such as glass cutting, engraving, painting, and coating, with products ranging from opaque glass beads and ornaments to transparent glass bottles, jars, flat glass, mirrors, and mosaic glass. The blowing method required glass viscosity lower than the core-forming and casting methods, with higher glass melt temperatures. At this time, glass furnaces were improved to increase melting temperatures, adapting to the requirements of the blowing method and improving glass quality and transparency accordingly.

From the 5th to third century BCE, the Sassanian Empire used the blowing method to produce daily glass bowls, cups, and bottles, decorating the surfaces with mold-made or hot-processed bead circle or oval patterns, known as famous Sassanian glass (Sasanian glass).

From 206 BCE to 220 CE, China was in the Han Dynasty period, progressing from small glass beads and jade rings to larger daily utensils and flat glass, with improved transparency58. The 16 green glass cups and glass animals and fragments unearthed from the early Western Han Dynasty serve as evidence. In the mid to late Western Han Dynasty tombs, glass spears and glass burial suits were unearthed, with the glass spear composed of sodium calcium glass rather than lead barium glass. Therefore, some scholars speculate that it was introduced from the West, while others believe that the spear’s shape is similar to that of bronze spears unearthed in other parts of China, suggesting it was domestically produced. During the Han Dynasty, glass was also referred to as Liuli, which has a more ancient meaning and has been used ever since.

The Wei, Jin, Southern, and Northern Dynasties period was a time of great cultural exchange between China and the West. Glass ornaments and containers were exported from West Asia to China through the Silk Road, and the glass blowing method also spread from Rome59. By the Northern Wei period at the latest, China had started using the blowing method to manufacture daily glass bowls, cups, and other hollow products. Particularly, during the fifth century, glass artisans from Persia were invited to China to blow glass bowls, cups, and pots using the mold-free method, with larger sizes and capacities, increased production, reduced costs, and glass not only imitating jewelry and jade but also used as daily utensils. Daily glass manufacturing and application thus entered a new phase53,54.

In the Sui Dynasty, which ended the division of the Southern and Northern Dynasties, the emperor ordered the restoration of glass production, inviting glass craftsmen from the Central Asian region to produce glass. High lead glass composition was adopted for the blowing method, producing green glass bottles, cups, and plates60.

During the Tang Dynasty, political unification and economic and cultural prosperity provided favorable conditions for glass development61. Glass composition evolved from lead and barium of the Han Dynasty to high lead, later applying sodium and calcium. Forming methods included die pressing, casting, free forming, and blowing. Various glass products were produced, imitating jewelry such as jade rings, sword ornaments, beads, and fish charms, as well as special supplies for the royal family, such as Luo Guo, gourd bottles, cups, and cup stands.

In the eighth century, the Arab region produced perfume bottles, tableware, utensils, and lamps of various sizes, shapes, and colors, with distinct Islamic cultural characteristics in their design and decoration, becoming known as Islamic glass62. From the 9th to twelfth centuries, Arabs also made achievements in surface decorations such as gilding, painting, enamel, and engraving. Most Islamic glass was sodium calcium silicate, with only a few being high lead glass composition.

From 960 to 1234, the Song, Liao, and Jin Dynasties period saw significant achievements in ceramic manufacturing but only maintained the Tang Dynasty level in daily glass manufacturing, with no significant breakthrough. The Liao Dynasty had frequent glass exchanges with West Asia, and in recent years, Sassanian, Byzantine, and Islamic style glass cups and bottles have been unearthed in Northeast China and Inner Mongolia.

In 982 CE, Venice began manufacturing glass, reaching its peak from the 13th to seventeenth centuries. Since 1291, it has been a world glass center, producing cups, water pitchers, wine pitchers, plates, perfume bottles, trays, mirrors, glass ornaments, and display items, sold throughout Europe63. The narrow sense of Venetian glass specifically refers to the glass produced on the island of Murano in Venice. From the fifteenth century, Venetians used relatively pure quartzite and re-crystallized white pure soda as raw materials, producing glass with fewer impurities, good whiteness, and high transparency, changing the impression of previous opaque and blurry glass. This glass was similar to crystal, hence called crystal glass (Cristallo). Previously, blown glass mostly used mold-free forming methods, but Venetian glass products mostly used mold blowing methods. During the forming process, they used crushed flowers (blooming flowers), mesh patterns, colored stripes, and agate (imitation marble) for decoration. Surface treatment methods included engraving, gilding, enameling, and painting, often combined in various surface treatments to form the unique Venetian decorative style. This glass produced in the Venetian area with Venetian decorative style can be called Venetian style glass, or broadly Venetian glass products.

In the twelfth century, Bohemia (present-day western Czech Republic) had many glass factories producing engraved glass products, known as Bohemian glass (Bohemian glass). Around 1700, Bohemians used potassium-containing plant ash and relatively pure quartz raw materials to produce potassium calcium silicate glass, which had higher transparency than Venetian glass and was named Bohemian crystal glass (Crystalex), still in production today.

From the 13th to seventeenth centuries, the Yuan and Ming Dynasties in China saw the development of daily glass production and application compared to the Song and Jin Dynasties. The Yuan Dynasty established the Guan Yuju Bureau, whose functions included glass production. At this time, glass was called "Guanyu," referring to the glass made using medicinal substances in a pot, similar to the Song Dynasty’s "Yaoyu." At the end of the Yuan and the beginning of the Ming Dynasties, glass workshops were primarily in Yanshen Town, Yidu County, Qingzhou Prefecture, Shandong. There were large furnaces for melting raw materials into glass, directly forming daily glass products, as well as drawing glass rods for lamp workers to make "glassware." There were also bead furnaces, specializing in producing beads. Glass varieties included various shapes and colors of glass beads, hairpins, earrings, teapot tops, chess pieces, wind chimes, chandeliers, screens, blown light bulbs, fish tanks, water pots, fire pearls, and more.

In the seventeenth century, daily glass production in the West shifted from northern Italy to countries such as Britain, Germany, and France. In the 1670 s, Englishman George Ravenscroft developed lead glass, namely the potassium lead silicate composition system64. The characteristics of this glass were easy melting, long material properties, capable of forming complex shapes, low hardness, easy to engrave, and most importantly, high transparency and gloss, more similar to crystal than Venetian and Bohemian crystal glass. This was named lead crystal glass and is the predecessor of today’s crystal glass.

Ancient cases of glass imitation jade

The ancients advocated the use of jade, and there was a high demand for jade in various Chinese dynasties. For instance, during the Warring States period, the local jade resources in the Hunan region, which is the origin of Chu culture, were scarce and transportation was inconvenient, making it impossible to meet people’s needs. However, Chu also served as an important area for glass production in ancient China, leading to the widespread use of glass as a substitute for jade in this region. This phenomenon directly influenced later dynasties such as Han, Sui, and Tang. Consequently, most of the glass imitations of jade unearthed today originate from Chang’an (now Xi’an) and Luoyang. Chang’an was the capital of the Western Han Dynasty, and Luoyang was the capital of the Eastern Han, Sui and Tang Dynasties. These capitals were the political, economic and cultural centers of their respective dynasties. Due to geographical barriers posed by Qinling Mountains and Taihang Mountains, it became challenging for ordinary people to obtain good quality local jade materials. However, lead-barium glass raw materials are rich in silicon dioxide content. With improved living standards came an increased desire for the wearing of jade jewelry in spiritual practices and daily use of jade utensils. Additionally, funeral culture became prevalent. Therefore, people used local materials to imitate the special cultural characteristics of jade, including opacity, translucency, or having a crystal texture, resembling the moist appearance of jade through glass-burning techniques.

Glass imitation jade

Bi is one of the most traditional utensils in China. “Shuowen” defines Bi as “auspicious jade, also a round vessel”, thus establishing the basic form of Bi’s design. “Eya·Shiqi” said: “The meat is good as the Bi, the meat is good as the Yuan, and the meat is good as a ring.” It distinguishes the proportion characteristics of Bi, Yuan and Huan from the modeling. In ancient China, Bi was mainly used as a sacrificial vessel and a funerary object. Its appearance was earlier. Archaeology shows that it was first unearthed in the Neolithic Age. The shape of the circular Bi was slightly later than tools such as stone axes. In the Stone Age period, the shape of the Bi was derived from the annular stone axes. The shape of the Bi is mostly flat, and there are also approximate squares, rectangles, ellipses, etc. Bi has both independent and multi-layer types. In the decoration of the surface, some are plain, and some are decorated. The unearthed Bi of each dynasty is mainly made of jade, as well as stone, pottery, ivory, crystal and glass. The ancients used glass materials to imitate jade Bi, which is enough to be considered counterfeit. The unique lead barium glass in China has a certain degree of turbidity or appears semi-transparent and milky due to the firing temperature. Its appearance is similar to that of jade, and it is smoother and cleaner than jade. Craftsmen can make molds through lost-wax casting to obtain preliminary shapes and patterns, and then use cold processing techniques to imitate high-quality jade by cutting, grinding, and polishing. Table 1 compares typical vessels made of glass and glass imitations of jade.

The three glass Bi found along the Silk Road all originate from tombs and exhibit shape characteristics consistent with jade Bi. This imitation of jade Bi in glass reflects a unique cultural phenomenon in ancient China. The discs have a circular shape with a hole in the middle. The decorative patterns of these glass discs, unearthed along the traditional Silk Road, exhibit distinct characteristics of their respective eras. Two of them are from the tombs of the Han Dynasty. The decorative patterns on the Bi’s surface are similar to the Pu pattern and the bud valley pattern on the jade Bi of the Warring States period. The other piece is from the Tang Dynasty, and the decorative pattern is the dragon and phoenix ruyi pattern, as shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5.

The glass wall with dragon and phoenix pattern unearthed from the Jingling Mausoleum of Tang Xinzong in Nanling Village, Qianxian County, Shaanxi Province ( The picture is quoted from the "Complete Collection of Chinese Gold and Silver Glass Enamel 4 Glassware" Fig. 92 ). One side is decorated with dragon pattern and the other side is decorated with phoenix pattern. There is a cloud pattern opposite to dragon and phoenix. Due to the corrosion of the soil, the surface of the glass wall has formed a calcified layer. This suitable pattern decoration shows more freedom in technique than the geometric pattern decoration of the Han Dynasty.

Puwen and Yagu patterns are the main decorations on the surface. Puwen primarily employs a geometric protrusion formed by multiple staggered tangent lines as the most basic unit, the bud grain pattern mainly uses a circular rotation pattern similar to bean sprouts as the most basic unit. Both patterns are covered with the body through four continuous decorative techniques. These two patterns are the most typical wall decoration patterns in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. These two glass walls have adopted the same decorative patterns and decorative techniques as the jade wall.

Glass imitation jade

The jade ornaments worn during the Warring States Period, Qin and Han Dynasties were exquisitely beautiful. Even small jade accessories such as jade huang, jade bi, and jade hen were intricately connected with silk threads to form a set of various adornments that accentuated the wearer’s splendid dignity. Over time, men gradually wore fewer various pendants after the Wei and Jin Dynasties, eventually opting only for simple jade pendants in later dynasties, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. However, women continued to wear various pendants for an extended period, often fastening them onto their belts to create a melodious jingling sound as they walked, pleasing to the ear. Consequently, “ring wear” gradually became a term for these women’s accessories. The style and wearing method of the ring pendant have continuously evolved over time. The Qing Dynasty scholar Ye Mengzhu mentioned in "Yue Temple·Inner Manor": "The ring is made by weaving gold threads into floral beads, adorned with pearls, gems, and bells, arranged in a row, and then placed over the chest." In Fanqin’s poems,“Meiyu” refers to admiration for jade or expressing such admiration through writing. The ancients’ love for jade stemmed not merely from its preciousness but also from its inherent qualities. As the old saying goes: “as a gentleman there is no reason not to take jade, to maintain a good image and moral bottom line”.

A half-moon glass decoration was unearthed from the Tang tomb of Jia Zhuang in Shangcai County, Henan Province. (The picture is quoted from “Cleaning Brief of Jia Zhuang Tang Tomb in Shangcai County, Henan Province”). Two more semicircles are dug out on the diameter of the semicircle, and three more holes are dug out along the edge of the semicircle arc. Both sides are relatively flat, with a width of about 5.9 cm and a height of about 2.5 cm. The texture is soft and the surface has white regolith.

Jade pieces similar to the shape of the glass with the dragon and phoenix pattern were unearthed from the Qingshan Six Dynasties tomb in Dangtu County, Anhui Province ( The picture is quoted from “Complete Collection of Jade unearthed in China” ( 6 ), page 158 ). The white jade is slightly transparent, the jade quality is warm, exquisite production, smooth lines. The surface is decorated with turtle pattern. Two pieces of jewelry material is different, the shape is slightly different, but the perforation position, outline structure is basically the same, the shape similarity is very high, and from the time point of view, it also has the relationship between the front and the back, may have a direct relationship with the modeling source.

Glass imitation jade cicada

In Sima Qian’s “Qu Yuan Biography”, it was recorded: “Cicadas shed their shells to escape from the polluted environment, detached from the mundane world, and not contaminated with the dirt of the mundane world”. The cicada lives in a filthy environment. After metamorphosis, it drinks only dew and produces silt without being stained. The ancients were happy to wear jade cicada to show their noble and clean identity. Additionally, the natural phenomenon of cicada’s transformation and reproduction conforms to the ancient Chinese people’s outlook on life of pursuing immortality, rebirth and nirvana. Therefore, cicada has become a totem with the meaning of eternal life. Placing a jade cicada in the mouth of the deceased means that the spirit is immortal, and the soul is expected to be reborn like a cicada. There are records of cicada-shaped adornment jade and funeral jade cicadas. Glass imitations of jade cicadas unearthed along the Silk Road were often placed in the deceased’s mouth or other orifices, which were common in Han Dynasty tombs. Most of them have the style of “Han Badao” at that time. The shape of the cicada is slightly triangular, and the eyes and abdomen of the cicada are obvious. The engraving was simple yet skillful, differing from earlier rounder and plumper jade cicadas, as shown in Fig. 8.

Jade cicada (photo taken in Gansu Provincial Museum). Unearthed from Mozuizi Han Tomb in Wuwei City, Gansu Province, jade cicada, white jade, linear shape, thick in the middle, thin on both sides, clear head, eyes and mouth, simple and without losing detail, strong and powerful knife. The shape of this cicada is realistic and is a typical representative of jade cicada carving in Han Dynasty.

Glass imitation jade ware

There are many kinds of glassware unearthed from the traditional Silk Road, featuring various shapes and decorations. Both casting molding processes and blowing molding processes can be found among them. The shapes of domestic glassware are greatly influenced by traditional Chinese ceramics, as well as gold and silver wares. Imitation jade wares are more commonly seen in small utensils such as relic bottles, gourd-shaped glass bottles, and abalone-shaped glass bottles, as shown in Fig. 9

Literature research on glass imitation jade

Wang discussed the age, spatial distribution, user, decorative pattern, size and other archaeological information of lead-barium glass. Combining chemical powder analysis and simulation experiments, he explored the jade like texture and composition of lead barium glasses, and studied the origin of lead barium glass based on the current research status5. Lead-barium glass was widely used in the Warring States period. In the study of tombs, it was found that there were few jades and their ornaments. The types of glassware were similar to jade ornaments, indicating that lead-barium glassware was closely related to jade ornaments. Glass was used to imitate the shape, luster, color and other properties of jade video to make up for the scarcity of jade resources, and to explore the chemical principle of imitation jade. However, there is no fixed formula for imitation jade with glass. This study helps scholars understand the production and significance of lead-barium glass in the Warring States period, to determine the significance of lead-barium glass to make up for the scarcity of jade resources, and to further explore its development direction and strategy in the sustainable development of glass technology. Christopher studied the production and use of lead-barium glass from the Warring States period to the Han Dynasty (475 BCE to 220 CE). He discussed the origin and decline of lead-barium glass in China, and the debate on the independent invention of Chinese glass. It is proposed that lead-barium glass is the main glass system in China, mainly used to imitate precious materials such as jade. The cultural value of this process and its significance to the symbolic meaning and continuation of traditional jade culture are discussed with a positive attitude.

Conclusion

-

(1)

In China, glass technology has not played a decisive role in the development of glass technology along the Silk Road. On the contrary, people’s orientation of materials, the purpose of process manufacturing, and the influence of traditional aesthetics have made the glass process always been on the edge of mainstream aesthetics, depending on the existence of jade, porcelain and gold and silver crafts. From the Han Dynasty to the Tang and Song Dynasties, the glass material gradually changed from lead-barium glass to lead glass, and with the technological progress and the increase of firing temperature, the glass products with high transparency, such as transparent water cups and wine utensils, were developed. However, the concept of imitation jade is still deeply rooted, and the mainstream aesthetics has hindered the progress of glass technology. For a long time, glass has not been developed as an independent process category. Glass academic circles agree that the concept of imitation not only limits the application of glass, but also hinders the development of glass technology. Even in the glass manufacturing technology, the glass technology in the Ming Dynasty has been very mature, and the whole process of glass making has been recorded in detail in the “Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century”, but this has not accelerated the development of glass technology. The concept of imitation jade has become an important factor in the slow development of glass art.

-

(2)

To sum up, in today’s era of special emphasis on technology, examining the historical process of Chinese glass technology may bring more thinking beyond the technical level to the theoretical research of process history. It is very one-sided to regard glass imitation jade as a historical problem and an obstacle to the development of glass technology. From the perspective of sustainable development, in the context of the maturity of contemporary technology, glass, as a common material, has rich raw material resources, simple and convenient processing technology, environmentally friendly and sustainable characteristics, and irreplaceable advantages, which meets the requirements of sustainable development of natural resources.

-

(3)

At the same time, contemporary art aesthetics tend to reinterpret traditional culture in a modern way. By deconstructing and reorganizing the ancient traditional glass technology and the unique Chinese cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade”, it not only helps to protect the gradually scarce jade mineral resources, but also promotes the inheritance of Chinese jade culture. Through the unique artistic language of glass, such as translucent, frosted and strong particle characteristics, artworks are created. Simultaneously, advanced 3D printing glass technology is applied to the restoration and protection of ancient cultural relics, contributing to the sustainable development path of the cultural phenomenon of “glass imitation jade”. In the context of modernization, these efforts help to achieve the sustainable remodeling and cultural revival of traditional Chinese Silk Road culture.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cormack, P. Arts & crafts stained glass (Yale University Press New Haven, 2015).

Basirico, L. A. The art and craft fair: A new institution in an old art world. Qual. Sociol. 9(4), 339–353 (1986).

Copple, M. Considering Wisdom: Gold or Wisdom-What Will It Be? (WestBow Press, 2020).

Qi Xiaofan. A study of Job 42. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University (2016).

Gumus, C. H. & Walker, S. Design for grassroots production in eastern Turkey through the revival of traditional handicrafts. Des. J. 20(sup1), S2991–S3004 (2017).

Fan, K. K. & Feng, T. T. Discussion on sustainable development strategies of the traditional handicraft industry based on Su-style furniture in the Ming dynasty. Sustainability 11(7), 2008 (2019).

Gan, F. Ancient glass research along the Silk Road (World Scientific, 2009).

von Richthofen F. China: Ergebnisse eigener Reisen, und darauf gegründeter Studien. Verlag von Dietrich Reimer (1882).

Stošić, S. The ancient maritime silk road: a shift to globalization. Uluslararası Medeniyet Çalışmaları Dergisi. 3(1), 304–320 (2018).

Abe, Y. et al. Ancient glassware travelled the Silk Road: Nondestructive X-ray fluorescence analysis of a fragment of a facet-cut glass vessel collected at Kamigamo Shrine in Kyoto, Japan. J. Archaeol. Sci.: Rep. 20, 362–368 (2018).

Abe, Y., Shikaku, R. & Nakai, I. Ancient glassware travelled the Silk Road: Nondestructive X-ray fluorescence analysis of tiny glass fragments believed to be sampled from glassware excavated from Niizawa Senzuka Tumulus No. 126, Japan. J. Ar-chaeol. Sci.: Rep. 17, 212–219 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. Silk Road glass in Xinjiang, China: Chemical compositional analysis and interpretation using a high-resolution portable XRF spectrometer. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39(7), 2128–2142 (2012).

Haksöz, Ç., Seshadri, S. & Iyer, A. V. Managing supply chains on the Silk Road: Strategy, performance, and risk (CRC Press, 2011).

Suocheng, D. et al. Resources, environment and economic patterns and sustainable development modes of the Silk Road Economic Belt. J. Resour. Ecol. 6(2), 65–72 (2015).

Goodman, B. D. Traveling the Silk Road: A measurement analysis of a large anonymous online marketplace. Comput. Rev. 55(7), 446–447 (2014).

van Hout, M. C. & Bingham, T. ‘Silk Road’, the virtual drug marketplace: A single case study of user experiences. Int. J. Drug Policy 24(5), 385–91 (2013).

Liu, J. Cultural trade between china and other countries along maritime silk road: Characteristics and status quo. J. Coastal Res. 107(SI), 351–5 (2020).

Cheng, Q. et al. Characteristics of chemical composition of glass finds from the Qiemo tomb sites on the Silk Road. Spectroscopy Spectral Anal. 32(7), 1955–1960 (2012).

Li, Z., Sui, D. Land Urbanization Level of Core Cities in the Silk Road Economic Belt. International Conference on Modern Management.(2017).

Islamov, A. K., Ibragimova, E. & Nuritdinov, I. Radiation-optical characteristics of quartz glass and sapphire. J. Nuclear Mater. 362(2–3), 222–226 (2007).

Itoh, T., Mugiraneza, J. D. D. & Miyahira. T., et al. P-190L: Late-News Poster: Thermal Durability of Poly-Si Films on Highly Engineered Glass for RTA Processes Enabling Advanced TFTs. SID International Symposium: Digest of Technology Papers. (2010).

Potuzak, M., Mauro, J. C., Kiczenski, T., et al. Communication: Resolving the vibrational and configurational contributions to thermal expansion in isobaric glass-forming systems. J. Chem. Phys. 133(9) (2010).

Sciau, P. Nanoparticles in ancient materials: The metallic lustre decorations of medieval ceramics. IntechOpen. (2012).

Zheng, S. P., Chen, X. & Zhao, B. H. Researching and production technology of golden yellow microcrystalline glass. Adv. Mater. Res. 430–432, 1261–1264 (2012).

Ren, X. L. Study on Islamic glassware unearthed from the underground palace of Famen temple. Cultural Relics Museol. 01, 68–72 (2011).

An, J. Y. A preliminary study of early Islamic glassware unearthed in China in recent years. Archaeology 12, 1116–1126 (1990).

Ren, X. L. Exotic treasures: Islamic glassware unearthed from the underground palace of Famen temple. Civilization 11, 56–65 (2014).

Vostrukhin, A. et al. Test facility for nuclear planetology instruments. Phys. Particles Nuclei Lett. 13, 224–233 (2016).

Zhan, X. & Walker, S. Craft and Design for Sustainability: Leverage for Change. In Proceedings of the 7th International Associa-tion of Soieties of Design Research, Cincinnati, OH, USA. 1–3 (2017).

Fu, Q., Beall, G. H. & Smith, C. M. Nature-inspired design of strong, tough glass-ceramics. MRS Bull. 42(3), 220–225 (2017).

Siczek, K., Zatorski, H. & Chmielowiec-Korzeniowska, A., et al. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effect of silver-coated glass beads in mice with experimentally induced colitis as a new type of treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. In Pharmacological Reports. PR, 69(3) (2017).

Lü, Q. Q. et al. Natron glass beads reveal proto-Silk Road between the Mediterranean and China in the 1st millennium BCE. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3537 (2021).

Sun, Y. & Liu, X. How design technology improves the sustainability of intangible cultural heritage products: A practical study on bamboo basketry craft. Sustainability 14(19), 12058 (2022).

Babajanyan, A. & Franklin, K. Everyday life on the medieval Silk Road: VDSRS excavations at Arpa, Armenia. Aramazd Armenian J. Near Eastern Stud. 12(1), 154–82 (2018).

Guo, X. Y. The exchange and mutual learning between ancient Chinese glass crafts and foreign cultures. Shanghai Arts Crafts 11(1), 3537 (2024).

Chen, S. Y. & Hou, Z. L. Analysis of the ancient Silk Road and ancient Chinese glass. China Natl. Exhibit. 05, 87–88 (2019).

Church, S. K. The Eurasian Silk Road: its historical roots and the Chinese imagination. Cambridge J. Eurasian Stud. 2(2018), 1–13 (2018).

Fu, X. Narrative and cultural analysis of porcelain. Chinese Narratologies. 87–115 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Laser damage characteristics of indium-tin-oxide film and polyimide film. Infrared Phys. Technol. 99, 9980–9985 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Cheng, J. & LI, T., et al. China Design development based on trend-driven innovation strategy under the belt and road initiative. In Proceedings of the Advances in Ergonomics in Design: Proceedings of the AHFE 2018 International Conference on Ergonomics in Design, July 21–25, 2018, Loews Sapphire Falls Resort at Universal Studios, (Orlando, Florida, USA, Springer. 2019).

Cui, P., Chen, X. & Tan, R., et al. Announcement of 2019 International Conference on Silk-roads Disaster Risk Reduction and Sus-tainable Development. (Springer, 2019)

Yin, R. et al. Analyzing the structure of the maritime silk road central city network through the spatial distribution of financial firms. Emerg. Markets Finance Trade 56(11), 2656–2678 (2020).

Yu, H. et al. Massive automatic identification system sensor trajectory data-based multi-layer linkage network dynamics of maritime transport along 21st-century maritime Silk Road. Sensors 19(19), 4197 (2019).

Mamirkulova, G. et al. New Silk Road infrastructure opportunities in developing tourism environment for residents better quality of life. Global Ecol. Conserv. 24, e01194 (2020).

Zhao, S., Yan, Y. & Han, J. Industrial land change in Chinese Silk Road cities and its influence on environments. Land 10(8), 806 (2021).

Abson, D. J. et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46(1), 30–39 (2017).

Qin, Y. et al. The research of burning ancient Chinese lead-barium glass by using mineral raw materials. J. Cultural Heritage 21, 796–801 (2016).

Wang, R., Xu, Y. & Zhou, X. Study on the related problems of lead-barium imitating-jade glass in the Warring States period of China. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14(8), 159 (2022).

Cui, H. X. Reviewing the development of jade culture and its implications. Cult. Relics Identification Appreciat. 22, 98–101 (2023).

Qian, Z. Jade is the symbol of Chinese culture. Art Design 1(Z2), 236–239 (2024).

Xu, H. D. Analysis of the transmission paths of Hetian jade culture from the perspective of cultural enrichment in Xinjiang. J. Hetian Normal College 43(03), 78–83 (2024).

Adili, A. Hetian Jade and ancient Chinese jade culture. Xinjiang Local Chronicles 02, 62–64 (2021).

Zhang, Z. P. Reflections on the study of Chinese Jade artifacts and jade culture. Jianghan Archaeol. 06, 3–7 (2016).

Zhang, J. Buddhist glassware of Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties and Sui Dynasty in archaeological remains. Chinese Art Research. 3, 60–66 (2016).

Zhang, Y. Y. Research on the Glassmaking of Mesopotamia - Centred around the Investigation of Cuneiform Texts. Master’s Thesis, Xiamen University (2017).

Wang, Z. F. Characteristics of glass in early ancient China. Tiangong 3, 10–11 (2020).

Burill, H. & An Jiayao, R. On the origin of the Chinese word “glass”. Glass and Enamel. 5, 55–58 (1990).

Liu, X. L. A Comparative Study on the Ancient Glass of the Warring States to the Han Dynasty in Three Places of Hunan, Hubei and Guangxi. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University (2017).

Ren, Z. Z. Research on Glassware of The Wei, Jin, Southern, Northern, Sui, and Tang Dynasties. Master’s Thesis, SOOCHOW University (2020).

Liu, Y. Exploration on Sui and tang glassware unearthed in Guyuan Ningxia. Cultural Relics World 10, 15–19 (2021).

Guo, Tg. Silk Road treasure cold coagulation beauty: Analysis of the glass ware from the underground palace of Famen temple. Cult. Relics Identificat. Appreciat. 18, 20–22 (2021).

Tan, X. Transport and Influence of Islamic Glass on the Silk Road (8th -16th Century). Master’s Thesis, Jinan University (2020).

Cao, D. Venetian glass crafts. Decoration 1, 34–35 (2001).

Zhou, X. A preliminary study on the origin of british glass decoration style. Art. Hundred. 2, 182–184 (2007).

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the research funding received from the Humanities and Social Research Science Institute of the Ministry of Education (20YJC760034), and the R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (SM202310005009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., Z.W., and J.Z.; Data curation, S.H., Z.W.; Funding acquisition, S.H., Z.W.; Investigation, S.H., Z.W., and J.Z.; Methodology, S.H., Z.W.; Resources, S.H. and J.Z.; Writing–original draft, S.H.; Writing–review & editing, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., Wang, Z. & Zhu, J. Research on glass imitation jade culture in the ancient Chinese Silk Road. Sci Rep 15, 4674 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87468-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87468-9