Abstract

Deaf people experience ableism (able-bodied oppression), audism (hearing-ability oppression), and linguicism (sign language-use oppression) and this study investigated if internalizing these oppressive experiences predicts their mental health. Deaf participants (N = 134) completed a 54-item Deaf Oppression Scale, developed for this study with Ableism, Audism, and Linguicism Subtests, along with the Beck Depression Inventory-II and the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory. The Deaf Oppression Scale and its Ableism, Audism, and Linguicism Subscales carry good reliability and the model fit indices for a confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good fit. Sixteen (16%) percent (n = 22) of the sample had depression, 36% (n = 48) had state anxiety, and 64% (n = 86) had trait anxiety. Internalized ableism predicted greater characteristics and symptoms of depression, internalized ableism and linguicism predicted greater state anxiety, and internalized audism predicted greater trait anxiety. This is the first empirical evidence dissociating three types of oppression that deaf people experience and their separate and different effects on their psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The biodiversity of the human species includes individuals with different hearing levels, although the majority have similar abilities to hear (henceforth, hearing people). Schools, workplaces, and healthcare systems, for example, have infrastructures and practices that have been built by hearing people but might cause barriers to those of different hearing levels, including deaf and hard of hearing people1,2,3,4. While deaf individuals navigate institutional and systemic barriers, many also experience oppression and other people’s perception of them as broken, impaired, or disabled; this perception is known as ableism5,6. Deaf individuals often face unique challenges that other people with perceived disabilities do not face, specifically referred to as audism1,7: the negative perceptions, prejudice, and discrimination towards those who are deaf. Among deaf people, there is a smaller population that considers itself a cultural and linguistic minority and predominantly communicate in a signed language. They also face sociocultural challenges that are unique to only them because they use a signed language and so they frequently experience linguicism, the perception of a language as inferior to a mainstream language8.

Individuals with perceived disabilities, including deaf people, face higher practical and social challenges compared to those who identify as able-bodied9,10,11. Individuals who are perceived as different frequently experience oppression, including negative unconscious bias, prejudice, microaggressions, and discrimination12,13,14. Oppression represents a state in which one group has more power and privileges than another, resulting in the maintenance of inequality and the domination of one group over the other13,15,16. In this context, internalized oppression is a process wherein individuals from a discriminated group internally adopt and internalize negative beliefs about their own group, derived from the beliefs of the dominant social group15,16,17,18. The process of transitioning from experiences of discrimination to internalized oppression can be gradual and may result from repeated incidents of discrimination. Individuals experiencing discrimination are often exposed to negative stereotypes and prejudices associated with their social group, which can become internalized and accepted as an integral part of their identity, leading to beliefs in their own inferiority. As a result, individuals may internally accept these norms as real or appropriate, resulting in the internalization of oppressive beliefs and behaviors. Internalized oppression can occur in many marginalized social groups. This can take a variety of specific forms, such as internalized racism or internalized sexism19.

In Poland, the experiences of deaf individuals have been shaped by systemic ableism, linguicism, and audism. Historically, deaf people have long been marginalized in educational systems, especially after the 1880 Milan Conference where mostly hearing educators came together to ban sign language in deaf education20. Before this decision, the Institute for the Deaf, established in 1817 in Warsaw, used Polish Sign Language (PJM) as the language of instruction in the classroom and published a PJM dictionary21. PJM is a natural language, like many other signed languages in the world that are full-fledged visual-gestural languages with their own grammar and structures, independent of spoken languages. Signed languages are not written languages; rather, they serve as the primary means of communication for many deaf communities worldwide. However, oralism, which dominated Polish deaf education until the late 1970s, emphasized speech and speechreading while discouraging the use of sign language. In the 1980s, signed Polish, an artificial sign language made by teachers, began to be introduced in schools, reflecting educational authorities’ preference for a system closer to spoken Polish. This was and is a clear example of linguicism, devaluing PJM as a legitimate language and prioritizing a system rooted in the dominant spoken language22,23.

In 2011, PJM was officially recognized with the enactment of the Act of 19 August 2011 on Sign Language and Other Means of Communication, which guarantees the right of Deaf citizens to choose their preferred form of communication in interactions with Polish public institutions24. Challenges persist, including limited accessibility to public services, systemic biases in education and employment, and societal stereotypes portraying deafness as a defect rather than a cultural and linguistic identity. For example, in the education system, many schools lack qualified PJM-Polish interpreters and/or many teachers are not proficient in PJM, severely limiting access to knowledge among deaf students. In the workplace, deaf employees often face discrimination due to the absence of appropriate accommodations such as communication technologies. Additionally, in daily life, deaf individuals encounter barriers in accessing public services, such as a shortage of PJM interpreters in hospitals or government offices. These systemic barriers exemplify ableism and audism and highlight the need for greater advocacy and legal protections for the Polish Deaf community. Preliminary qualitative studies conducted in Poland confirmed that Deaf individuals experience various forms of oppression, including audism, with significant psychological and social consequences25.

The minority stress theory classifies internalized oppression as a proximal stressor, resulting in negative mental health consequences for people from social minorities26,27,28. Individuals who experience discrimination frequently struggle with feelings of rejection, low self-esteem, and/or a lack of social support, which can further exacerbate anxiety and depressive symptoms29,30,31. A meta-analysis of the relationship between internalized oppression and health found that internalized racism had a strong, direct impact on both mental and physical negative health outcomes32. Individuals who internalize negative attitudes and beliefs about their own group may experience issues such as: (a) low self-esteem33,34; (b) anxiety35; (c) depression36,37,38,39; (d) body image40; and (e) substance abuse41. Those subjected to oppression may also be more vulnerable to experiencing traumatic life events and exhibit a limited capacity to counteract internalized oppression19. Internalized oppression is one of the many facets affecting deaf individuals when they internally adopt and believe in society’s oppressive attitudes and perspectives of them3,42. This is a concerning public health issue because numerous studies of deaf children and adults around the world confirm the high rate of mental health issues among deaf individuals43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. A Danish study45 found that additional disabilities and the feeling of being discriminated against significantly and independently explained deaf individuals’ degree(s) of psychological well-being. In Poland, deaf people who communicate in spoken Polish demonstrated that there is a relationship between a sense of disability and depression whereas those who had a greater sense of disability had more depressive symptomatology52. Here, we were interested in: (a) how to measure deaf-related oppression (ableism, audism, linguicism), including the psychometrics of a scale developed for this study, and (b) if internalized, deaf-related oppression can explain some of the anxiety and depression symptomology found in deaf adults.

Research design

A quantitative research design was used in this study with one sample of deaf adults. A deaf-related oppression scale (henceforth, Deaf Oppression Scale or DOS) as developed to measure the effects of internalized ableism, audism, and linguicism. The psychometric properties of this scale were tested as described in the analysis plan in the Method section. A background questionnaire, standardized measures of depression and anxiety, along with the DOS, was administered to this sample. The following hypotheses were generated:

Hypothesis 1. Psychometric analyses will support the reliability and validity of the DOS and its subscales, which assess internalized oppression resulting from ableism, audism, and linguicism among Polish deaf adults.

Hypothesis 2. The DOS subscales will account for some of the variance in depression symptomology, with internalized oppression contributing to the severity of depressive symptoms, as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory-II, among Polish deaf adults.

Hypothesis 3. The DOS subscales will account for some of the variance in anxiety symptomology, with internalized oppression being associated with higher anxiety levels, as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, among Polish deaf adults.

Method

Participants

The study included 134 adults from Poland between the ages of 18 to 64 years old (M = 32.4; SD = 8.8) who self-reported what is known in the medical field as clinical or atypical bilateral hearing levels in the profound or severe hearing loss ranges. The majority of the 134 participants were born deaf (79.1%; age deaf M = 0.7, SD = 1.6 years old). The study originally had 147 participants, with 13 excluded from the analyses because they self-reported moderate or mild hearing loss. Table 1 documents the sample’s demographic and background characteristics: city/town population, sex, education, preferred language, parent hearing level, hearing level, and assistive technology use. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, and was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed about the voluntary and confidential nature of their participation in the study and about their right not to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Materials

Background questionnaire

A written questionnaire requested information about participants’ age, residential population, sex, education, preferred language, parental hearing level, and assistive technology use.

Deaf Oppression Scale

The Deaf Oppression Scale (DOS) is a written questionnaire designed to measure internalized oppression among deaf individuals and includes 54 items divided into three subscales: ableism, audism, and linguicism. The items were developed first through interviews with deaf individuals about their experiences with oppression25,53. This inclusion of firsthand experiences was crucial in ensuring that the scale accurately reflected the perspectives and realities faced by deaf individuals, thereby enhancing the face validity and relevance of the scale for measuring experiences of ableism, audism, and linguicism. The scale was designed from the outset with 54 items, based on the dimensions identified in the interviews, and no items were reduced from a larger pool. The preliminary items, along with the three subscales, were pre-decided based on these interviews and further developed and refined through pilot testing to ensure their relevance and clarity. The final items were administered to a sample of 26 deaf individuals. DOS items are on a 7-point Likert scale and each subscale, with 18 items, had a sum of scores that ranged from 18 to 126. Higher scores signified a heightened degree of internalized oppression related to audism, linguicism, and ableism. The DOS is the first scale specifically designed to measure internalized oppression and the experiences of ableism, audism, and linguicism among deaf individuals. It captures the psychological and sociocultural impact of oppression on identity and self-perception. Other scales used in past research such as the Deaf Acculturation Scale54 measures the degree to which individuals acculturate within the deaf community, hearing community, or both, highlighting the cultural dimensions of being deaf. These differences illustrate that while both scales address aspects of Deaf experience, the DOS uniquely centers on the internalization of oppression and its effects, which are not covered by the DAS.

Beck Depression Inventory

The written Polish version55 of the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)56, was used to document participants’ level of characteristics and symptoms of depression. The BDI-II was chosen because of its wide use, the availability of BDI-II data on deaf individuals in other countries, and the availability of a written Polish version. The BDI-II consists of 21 self-report items, and participants were tasked with evaluating each of the items using a four-point response scale. Item scores ranged from 0 to 3 points and the overall sum of scores range from 0 to 63 with 0–13 representing no or minimal depression, 14–19 mild depression, 20–28 moderate depression, and 29–63 severe depression.

State and trait anxiety inventory

The State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)57 was used in this study because it is widely used in medical research and because a written Polish version was available58. The STAI consists of two scales, State Anxiety Subscale (STAI-S) and Trait Anxiety Subscale (STAI-T) comprising 20 statements each and participants assessed their responses using a 4-point Likert scale, where ‘1’ indicated ‘not at all’ or ‘almost never’ and ‘4’ indicated ‘very much so’ or ‘almost always.’ Scores for each scale range from 20 to 80 points, with scores 20–37 representing no or low anxiety, 38–44, moderate anxiety, and 45–80 high anxiety. The score for each scale was calculated as the sum of responses, with a higher score indicating a higher level of anxiety. State anxiety is defined as hyperarousal and a temporary emotional response to a stressful situation, which can occur at various points in life and depends on external factors such as stress, threat, or uncertainty. Trait anxiety is defined as persistent tendency to attend to and experience fear, worry, and anxiety across many situations59.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from Polish associations of Deaf people and local branches through presentations in PJM offered by the first or second author. Prior to the study, all participants were informed about personal data protection and regulations regarding limited access to this data. They were also thoroughly introduced to the purpose of the study and their informed consent was requested to participate. Participants were given the BDI-II and STAI questionnaires and they had the option to consult a PJM interpreter to ensure full language access to the questionnaire items. The interpreter was available to interpret single items that needed clarification, multiple items, or the whole forms. The interpreter facilitated communication only while participants independently completed the questionnaires.

Furthermore, a psychologist fluent in PJM, as well as spoken and written Polish, supervised the process and addressed procedural questions as needed. Participants completed all the forms independently; the interpreter did not receive or record the participants’ responses to items. The psychologist and interpreter’s roles were strictly limited to ensuring accessibility and procedural clarity without influencing the content of participants’ responses in order to avoid response biases. Testing took place at the University of Warsaw Faculty of Psychology. Participants were tested individually to accommodate their preferred communication methods. Participation took approximately 30–60 min and participants were paid for their time.

Analysis plan

Reliability of the DOS and subscales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha60, a measure of internal consistency that provides an estimate of the reliability of a scale by evaluating how closely related a set of items are as a group, and 95% confidence intervals were computed to provide a range within which the true reliability coefficient is expected to exist. An exploratory correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among individual items within and between subscales. This involved calculating pairwise correlations and identifying large correlations, which could indicate strong relationships between items. This analysis helps in understanding the inter-item relationships and potential redundancies or overlaps within and across subscales.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimation. DWLS is particularly suited for ordinal data since it provides more accurate parameter estimates compared to maximum likelihood estimation. The factor loadings obtained were fully standardized to facilitate interpretation. Model fit was assessed using several indices: (a) chi-square (χ2) results were reported to evaluate the discrepancy between the observed and model-implied covariance matrices; (b) comparative fit index (CFI) results reported the incremental fit index that compares the fit of the target model to a null model; (c) Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) provided another incremental fit index that takes model complexity into account; (d) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) provided a measure of how well the model, with unknown but optimally chosen parameter estimates, would fit the population’s covariance matrix; and, (e) weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) assessed the model fit by comparing the residuals. A CFI and TLI above 0.95 indicate excellent fit, and an RMSEA below 0.08 suggests a reasonable fit of the model to the data61,62.

An exploratory correlation analysis was conducted with participants’ background variables as listed in Table 1 with the outcome measure scores and subscale scores: DOS Total Score, Ableism Subtest Score, Audism Subtest Score, Linguicism Subtest Score, BDI-II Score, STAI-S Score, and STAI-T Score. The results of each mental health test (BDI-II, STAI) were then analyzed individually to: (a) describe the sample’s results (mean, standard deviation) and compare them with prior findings with other deaf and hearing samples using t-tests with p < .05; and, (b) assess if internalized oppression (DOS subtests) accounted for any of the variance found in the mental health tests using a regression analysis with any background variables that were found to be significant.

Results

There was no missing background nor DOS, BDI-II, or STAI data. The DOS psychometric results are first described, then the BDI-II and STAI results are described before the DOS predictors results are presented respectively.

Deaf Oppression Scale psychometric properties

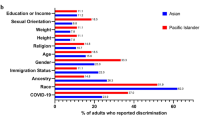

Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimates for the DOS, and its three subscales were above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating adequate reliability60. Specifically, the overall scale showed high reliability (α = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.89, 0.93), while the subscales demonstrated good reliability with Ableism (α = 0.78; 95% CI: 0.72, 0.83), Audism (α = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.73, 0.83), and Linguicism (α = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.82, 0.89). These results demonstrate that the DOS and Ableism, Audism, and Linguicism Subscales have good internal consistency. An exploratory correlation analysis revealed several large pairwise scale item statement correlations within the Ableism, Audism, and Linguicism Subscales and between subscales. A 54 × 54 correlation matrix is too large to include in this article, therefore multidimensional scaling (MDS) was used to visualize the similarity or dissimilarity of the items based on their correlations, see Fig. 1. MDS places each item in a low-dimensional space such that the distances between items reflect their dissimilarities. This approach provides a visual representation of the relationships among items, helping to identify clusters and patterns that may not be immediately apparent from a correlation matrix alone.

What was noteworthy in the exploratory correlation analysis was the strong pairwise item correlations within subtests and between subtests that were equal to or greater 0.05 (R = > 0.05). Within the Ableism Subscale, there were three pairwise correlations with R = > 0.05: Item 11 & Item 35 (R = .60, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.48, 0.70), Item 30 & Item 34 (R = .54, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.65), and Item 39 & Item 43 (R = .81, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.86). See Table 2 for item statements. Within the Audism Subscale, there was one pair-wise correlation with R = > 0.05: Item 31 & Item 33 (R = .51, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.63). Within the Linguicism Subscale, there were four correlations with that were R = > 0.05: Item 8 & Item 9 (R = .60, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.39, 0.64), Item 13 & Item 48 (R = .64, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.53, 0.73), Item 17 & Item 27 (R = .58, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.68), and Item 46 & Item 47 (R = .57, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.68). Correlation analysis between subscales illustrated six pairwise correlations with R = > 0.05 between the Ableism and Audism Subscales: Item 6 & Item 45 (R = .53, p = .002; 95% CI: 0.10, 0.41), Item 20 & Item 28 (R = .61, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.70), Item 29 & Item 53 (R = .51, p = < 0.001; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.62), Item 7 & Item 30 (R = .058, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.68), and Item 18 & Item 35 (R = .53, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.64). The Audism and Linguicism Subscales had three pairwise correlations that were R > .50: Item 4 & Item 18 (R = .50, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.36; 0.62), Item 4 & Item 36 (R = .50, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.36; 0.61), and Item 41 & Item 53 (R = .59, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.47; 0. 69). There were no pairwise correlations greater than 0.5 between the Ableism and Linguicism Subscale items. The within and between subscale findings suggest that there are strong relationships between certain items that may indicate underlying constructs that are well-defined and consistent across items. High correlations within subscales support the internal consistency findings, while correlations between subscales provide insight into how different constructs might relate to each other.

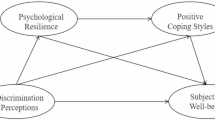

The results of the CFA model demonstrated large covariance for all pairs of subscales: Ableism and Audism = 0.89, Ableism and Linguicism = 0.64, and Audism and Linguicism = 0.89. This suggests that there is fairly large covariance for all subtest pairs, as found in the exploratory correlation plot (see Fig. 2 for visualization), with really strong covariance for each subtest when compared with the Audism subtest,. Table 2 illustrates the factor loadings for scale items by the three subscales. The model fit indices for the CFA indicated a good fit to the data: χ2(1374) = 3372, p < .001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.079 (95% CI: 0.075, 0.083). These indices meet the generally accepted criteria for a well-fitting model. The chi-square statistic, while typically significant in large samples, supports these findings when considered alongside the other fit indices. Overall, the CFA results suggest that the proposed factor structure is a good representation of the data, with each subscale adequately capturing its intended construct and the overall model demonstrating good fit.

To determine if participant background variables influenced their DOS responses, multiple analyses of variance were performed with Ableism, Audism, and Linguicism Subscales as the dependent variables and assistive technology use, hearing level, parent hearing level, and preferred language as the between-subject variables. The deaf adults who reported preferring Spoken Polish (M = 52.62; SD = 15.64) had higher Linguicism Subscale scores than those who preferred PJM (M = 40.81; SD = 13.53), F(21, 133) = 4.203, p = .043, partial eta squared = 0.036. There were no other significant main effects or any significant interactions (p > .05).

Internalized oppression effect on mental health

The mean and standard deviations of the deaf participants’ scores on the BDI-II, STAI-S, and STAI-T and their DOS subscale scores are presented in Table 3. The table also demonstrates significant (p < .001) bivariate correlations between all mental health scales and DOS subscales. The positive correlations suggest that there is a significant relationship between internalized oppression and mental health.

Depression

The first analysis of the BDI-II data was to determine if this sample’s depression symptomatology was similar to other studies. The deaf adult sample yielded the following results: 84% (n = 112) none or minimal depression; 9% (n = 13) mild depression; 6% (n = 8) moderate depression; and 1% (n = 1) severe depression. The Polish deaf adults in this study had depression levels in the non-clinical range, similar to Brazilian hearing young adults63, but significantly lower than those of Polish hearing adults55 and deaf and hearing adults in other countries64,65,66,67,68 (see Table 4 for means and t-test statistics). However, it is worth noting that the deaf adults from other countries, such as Spain64, Mexico65, and India67, took versions of the BDI-II that were adapted to their signed languages whereas in the present study, the deaf adults did not have a PJM version. The BDI-II scores among the Polish deaf adults who identified as male and female were not different, t(132) = 0.851, p = .396, but there was a significant negative correlation with age, R(134) = − 0.198, p = .022. This negative correlation suggests that older deaf adults had more depression symptomatology than the younger deaf adults. Analyses of BDI-II scores with other background variables revealed no correlation with education or group differences (p < .05) based on parent hearing level, preferred language, hearing level, and assistive technology use.

The second analysis, a linear regression, was performed to see how much internalized oppression accounted for variance in the sample’s BDI-II scores with age as a covariant. Internalized oppression explains approximately 16% of the variance in BDI-II scores, R = .450, R2 = 0.202 (adjusted R2 = 0.178), F(1, 133) = 8.183, p < .001. The regression analysis demonstrated that age and internalized ableism, but not audism nor linguicism, have an effect on depression. See Table 5.

State anxiety

The deaf adult sample yielded the following STAI-S results: 64% (n = 86) no or low anxiety, 25% (n = 33) moderate anxiety, and 11% (n = 15) high anxiety. The Polish deaf adults’ STAI-S scores were in the no or low anxiety range and similar to Polish hard of hearing adults but significantly higher than Polish hearing adults69 and American deaf adults70 but significantly lower than Serbian hard of hearing adults71; see Table 6 for means and t-test statistics. Analyses of background variables revealed no correlation with age (p < .05) and no differences (p < .05) based on sex or assistive technology use. Deaf adults with higher levels of education also had higher state anxiety scores, R(134) = 0.224, p = .009. Deaf adults with severe hearing levels (M = 36.6, SD = 8.5) had higher state anxiety scores compared to those with profound hearing levels (M = 32.7, SD = 8.6), t(132) = 2.303, p = .023 (95% CI: 0.544, 7.187). Deaf adults who preferred spoken Polish (M = 37.0, SD = 8.3) had higher state anxiety scores than those who preferred PJM (M = 31.2, SD = 8.2), t(132) = -4.001, p = < 0.001 (95% CI: -8.633, -2.920). Deaf adults with deaf parents (M = 35.3, SD = 8.6) had higher state anxiety scores compared to those with hearing parents (M = 30.8, SD = 8.3), t(132) = 2.860, p = .005 (95% CI: 1.3, 7.5). A linear regression was performed with the DOS subtests, R = .619, R2 = 0.383 (adjusted R2 = 0.349), F(4, 133) = 11.168, p = < 0.001, and the results demonstrated that internalized oppression explains approximately 20% of the variance in state anxiety scores (see Table 7 for summary of predictors). These findings indicate that having some hearing ability and internalized ableism and linguicism, but not internalized audism, predicts deaf people’s hyperarousal and their short-term, temporary emotional response to a stressful situation.

Trait anxiety

The result that seemed most alarming was that the deaf adult sample yielded the following STAI-T scores in the following ranges: 36% (n = 48) no or low anxiety; 38% (n = 51) moderate anxiety; and 26% (n = 35) high anxiety. The STAI-T mean score was in the moderate anxiety range and significantly higher than Polish hearing and hard of hearing adults69, but not different from Serbian hard of hearing adults71 (see Table 6 for means and t-test statistics). No correlations (p < .05) were found with age or education and no differences (p < .05) were found based on sex, parent hearing level, preferred language, hearing level, or assistive technology use. A linear regression was performed with the DOS subtests, R = .464, R2 = 0.215 (adjusted R2 = 0.197), F(3, 133) = 11.879, p = < 0.001, and the results demonstrate that internalized oppression explains approximately 21% of the variance in trait anxiety scores (see Table 8 for summary of predictors). These findings suggest internalized audism, but not ableism nor linguicism, predicts greater persistent tendency to attend to and experience fear, worry, and anxiety across many situations.

Discussion

This study presents the first empirical evidence documenting the different and separate effects of ableism, audism, and linguicism. This is important because those not familiar with Deaf Studies might assume that deaf people, particularly signers, have the same oppressive experiences as other people with perceived disabilities. The finding that oppression has adverse effects on mental health provides additional empirical evidence supporting the Minority Stress Theory26,27,28 and sheds light on the public health crisis in deaf people’s psychological well-being as they navigate oppressive experiences in their lives.

Age and internalizing ableism predict depression in the deaf community. The findings that deaf participants’ ages negatively correlated with depression supports other studies findings that older adults, with their accumulated experiences, seem to be better prepared to manage these difficulties effectively. This manifests in a lower intensity of depressive symptoms compared to younger adults72. A recent study of young deaf adults in the United Kingdom found that only a few deaf young people scored high for subjective well-being and that 42% of deaf young people had probable or possible depression73. An American study of deaf adults also suggested that they are susceptible to depression, possibly due to early stressful experiences and limited access to language, information, and appropriate healthcare47. The significant impact of internalized ableism on the severity of depression was found in another study with hearing adults74 that observed the perception of lesser worth in the context of internalized ableism. That study found that this depression could lead to avoidance of social interactions and exacerbate feelings of isolation, which in turn may increase the risk of depression. The results of the present study highlight the need for further research into the mechanisms influencing these relationships; it could contribute to a better understanding and support of the mental health of deaf individuals.

Hearing level, education level, internalizing ableism, and internalizing linguicism predict state anxiety. High levels of anxiety as a state among deaf adults appear to be associated with several factors. Others have suggested that deaf individuals may experience social stigma and discrimination due to their disability, which can induce tension and fear of negative reactions from others75. In context where sign language is not widely used, deaf adults might experience feelings of isolation and increased anxiety47,76. Communication barriers and challenges with hearing individuals, who are not familiar with the deaf community, and limited understanding of environmental speech could generate frustration and stress, while deaf individuals may also feel social pressure to meet expectations and conform to societal norms, possibly leading to increased feelings of anxiety and insecurity. The observation that individuals with severe hearing levels often experience higher levels of anxiety than those with profound hearing levels could possibly be due to greater involvement in the hearing environment and continuous coping with communication barriers. Conversely, individuals with profound hearing levels, who are more often integrated into the deaf culture and community, may experience less anxiety due to a stronger sense of belonging and support. Similarly, those with higher levels of education who were observed to also have higher levels of state anxiety. This observation could be attributed to greater awareness of complex deaf and hearing sociocultural interactions in the public, at universities, and/or at the workplace.

Internalizing audism predicts trait anxiety. Studies suggest that trait anxiety is a neurobiopsychological arousal process found in animals and humans after experiencing frequent, intense, and/or enduring negative affect59. Those with high trait anxiety tend to have attentional bias towards threat77, enhanced memory of past threats78 and show slower physiological recovery after a stressor79,80. Unlike state anxiety that fluctuates often depending on present situations, trait anxiety is something that has become integrated in the individual during their personality development prior to adulthood. Some suggest trait anxiety is actually a personality trait—neuroticism—and may not be specific to anxiety-related disorders59,81. Like neuroticism, trait anxiety appears to be a nonspecific vulnerability factor that is a product of generalized vulnerability for anxiety and depression59, which is consistent with the present study’s finding of the STAI-T having strong positive correlations with BDI-II and STAI-S scores. Those with high trait anxiety have been found to have different brain structures and functions than those with no or low anxiety82,83,84. 64% (64%) of the deaf people in the current study had moderate or high trait anxiety, suggesting a lifetime of intense stress.

While this study focused on those with severe to profound hearing levels, a study of children with mild to moderate hearing levels (loss) displayed elevated cortisol levels compared to their peers with no hearing loss; in fact, their levels were similar to adults experiencing burnout85. Deaf adults constantly experience social and communication difficulties, trauma, and limited access to psychological support86,87, along with stigmatization and discrimination, which can result in internal conflict and the development of negative self-beliefs, thereby increasing trait anxiety levels. Furthermore, communication challenges often contribute to feelings of social isolation and uncertainty, both key variables in the development of anxiety. The lack of adequate social support and understanding from the environment can further exacerbate this condition. Deaf individuals also often experience violence or trauma that may further contribute to an increase in anxiety levels86,87. Additionally, pressure to conform to the norms of hearing society and the need to prove one’s worth can heighten anxiety. Limited access to mental health services, resulting from language barriers, impedes deaf individuals from receiving appropriate therapeutic support88,89,90. Moreover, educational and professional difficulties, stemming from a lack of system adjustments to the needs of deaf individuals, can intensify feelings of uncertainty and anxiety about the future. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the specific needs of deaf individuals and adjusting support systems to reduce the occurrence of trait anxiety.

The study findings suggest deaf Polish adults exhibit lower levels of depression compared to Polish hearing adults and compared to deaf and hearing individuals in other countries. It is possible that deaf individuals in Poland benefit from more effective mental health support mechanisms or are better adapted to handling challenges associated with being deaf. The availability of integrated healthcare services and specialized support programs may even have played a key role here. On the other hand, the higher level of anxiety, both as a state and a trait, compared to Polish hearing adults, suggests that deaf individuals in Poland may experience significant stress and anxiety levels. The causes could be communication difficulties, social stigmatization, and/or insufficient integration within society. Additionally, the higher level of anxiety may reflect uncertainties and concerns related to daily functioning in a predominantly hearing environment. To reduce anxiety symptomology in Polish deaf adults, it is crucial for psychological services that are tailored to the specific needs of the deaf community to provide more effective anxiety prevention strategies and interventions. Furthermore, promoting greater acceptance and understanding in society, through education about deafness and the elimination of communication barriers, may contribute to reducing anxiety levels and enhancing the overall quality of life for deaf individuals.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study was the first quantitative attempt to demonstrate different effects of ableism, audism, and linguicism on deaf individuals. It is crucial important to test the replicability of this study’s results in future studies. The DOS offers good psychometric properties to be used in other studies on oppression; nevertheless, as with the BDI-II and STAI, the DOS is a written test, which is a limitation for deaf individuals whose reading skills are not on par with their hearing peers91,92. It would be beneficial for future studies to have the DOS available in the participants’ sign language through a fixed video translation, with documented translation procedures and psychometric properties. Previous research has demonstrated the effective use of pre-recorded video translations for assessing outcomes in signed language, with studies such as Estrada et al.64 for the Spanish Sign Language version of the BDI-II and Rogers et al.93 for the BSL versions of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and WSAS demonstrating the validity of these methods. Recent studies have also shown equivalence between pre-recorded video and live-mode assessments, such as those by Rogers et al.94, which supports the use of pre-recorded video outcome measures in future studies.

Another limitation is the generalizability of the results since the sample may be a limited representation of the larger deaf community. The participants in the already-small sample from one country, and this small sample became even smaller when compared with different background characteristics. As a result, the sample might not fully reflect the diversity of the deaf population in Poland or in other countries. Furthermore, the results of this research may be influenced by the prevailing economic and socio-political contexts in Poland. A cross-cultural meta-analysis found that the country participants lived in accounted for 31% of the variance in trait anxiety95. Future studies should include deaf individuals with some hearing ability (hard of hearing individuals) and deaf individuals from other underrepresented minority populations. Research on internalized oppression within the deaf community is crucial for improving our understanding of the mental health of this group. For example, this study’s findings can provide valuable guidance to mental health professionals, including psychotherapists, psychologists, and social workers, who work with deaf individuals and are concerned with how internalized oppression may offer a crucial perspective in the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety and depression disorders within this community.

Future research is needed on the society’s perceptions of deaf people, the process by which deaf people internalize oppression, and the effects ableism, audism, and linguicism have on other aspects of well-being such as self-esteem, quality of life, and physical health. Such research is needed to provide more empirical evidence that ableism, audism, and linguicism are different theoretical constructs and can have different effects on deaf individuals’ wellbeing. While the present study focused on Polish deaf adults, it will be important to investigate if similar findings are found in deaf communities outside of Poland. Another important follow-up study would be a replication of the present study with the DOS, BDI-II, and STAI administered in PJM rather than written Polish. Outside of Deaf Studies, the DOS Ableism Subscale could be used by itself in similar future research with different disabled populations to investigate the effect of internalized ableism.

Conclusion

Deaf people experience and internalize different types of oppression, similar to other societal minorities, that clearly have adverse effects on their mental health. Such oppression is a violation of deaf people’s human rights according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities96. The findings in the present study support the significance of prioritizing discussions about oppression and provide three types of oppression—ableism, audism, and linguicism–for discussion among scholars, educators, and healthcare providers. In the United States, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has prioritized dismantling ableism to advance new discoveries and knowledge97 the National Science Foundation set priorities for studies that address biases98 and established funding to accelerate science partnerships to remove disability barriers, and the National Institutes of Health established funding mechanisms to increase the number of future biomedical scientists from underrepresented minority groups, including deaf people99. In Poland, the Government Plenipotentiary for Disabled People is responsible for initiating and implementing measures aimed at reducing the impact of disabilities, including barriers that hinder the full participation of disabled people, such as deaf individuals, in society100. This office also collaborates with non-governmental organizations supporting disabled individuals. Additionally, under the Polish Act on Sign Language and Other Means of Communication, the Polish Board of Sign Language was established as an advisory body to the minister responsible for social security101. The Board’s scope includes issuing recommendations for the proper use of sign language communication, promoting knowledge of PJM through initiatives supporting accessibility and opinions on the effectiveness of legislative measures while reviewing government documents affecting deaf people. Future work is needed to build optimal ways for reduction of deaf people’s experiences of oppression, protection and support for navigating life in a society with such perceptions, and advancement of the community’s well-being.

Data availability

All data have been made publicly available on OSF and can be accessed at https://osf.io/kts7u/.

References

Bauman, H-D-L. & Murray, J. J. Deaf gain: an introduction. In Deaf Gain: Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity (eds Bauman, H-D-L. & Murray, J. J.) xv–xiii (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Hauser, P. C., O’Hearn, A., McKee, M., Steider, A. & Thew, D. Deaf epistemology: deafhood and deafness. Am. Ann. Deaf. 154, 486–492 (2010).

Lane, H. Do Deaf people have a disability? In Open Your Eyes: Deaf Studies Talking (ed Bauman, H-D-L.) 277–292 (University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

Mauldin, L. Made to Hear: Cochlear Implants and Raising Deaf Children (University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

Bauman, H. L., Simser, S. & Hannan, G. Beyond ableism and audism: Achieving human rights for deaf and hard of hearing citizens. https://www.chs.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/beyond_ableism_and_audism_2013july.pdf (2013).

Campbell, F. K. Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Humphries, T. & Audism The making of a world. Unpublished essay. https://docs.google.com/document/d/16D6h6JxZy8z84y4XczSfcce6IBf33BJ41ErvdxWASZA/preview#bookmark=id.es4yxcrwabhb (1975).

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. Language rights. In Handbook of Bilingual and Multilingual Education (eds Wright, W. E. et al.) 185–202 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015).

Akram, B., Nawaz, J., Rafi, Z. & Akram, A. Social exclusion, mental health and suicidal ideation among adults with hearing loss: protective and risk factors. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 68, 388–393 (2018).

Bogart, K. R. & Dunn, D. S. Ableism special issue introduction. J. Soc. Issues. 75, 650–664 (2019).

Brown, R. L. & Ciciurkaite, G. Disability, ableism, and mental health. In Research Handbook on Society and Mental Health (ed Elliott, M.) 201–217 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2022).

Marks, A. K., Woolverton, G. A. & García Coll, C. Risk and resilience in minority youth populations. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 16, 151–163 (2020).

Torres, S. A., Sosa, S. S., Flores Toussaint, R. J., Jolie, S. & Bustos, Y. Systems of oppression: the impact of discrimination on latinx immigrant adolescents’ well-being and development. J. Res. Adolesc. 32, 501–517 (2022).

Williams, M., Osman, M. & Hyon, C. Understanding the psychological impact of oppression using the trauma symptoms of discrimination scale. Chronic Stress. 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/24705470221149511 (2023).

Bell, L. A. Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (eds Adams, M. et al.) 1–14 (Routledge, 2007).

David, E. R. & Derthick, A. O. What is internalized oppression, and so what? In Internalized oppression: The Psychology of Marginalized Groups (ed. David, E J. R.) 1–30 (Springer Publishing Company, 2014).

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. & Griffin, P. Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (eds Adams, M. e al.) 35–66 (Routledge, 2007).

Tomaszewski, P., Wieczorek, R. & Moroń, E. Audyzm a opresja społeczna [Audism and and social oppression]. In Kultura a zdrowie i niepełnosprawność [Culture, health and disability] (eds. Kowalska, J. et al.) 161–189 (Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2018).

David, E. J. R. & Derthick, A. O. The Psychology of Oppression (Springer Publishing Company, 2017).

Lane, H. The Mask of Benevolence. Disabling the Deaf Community (Knopf, 1992).

Hollak, J. & Jagodziński, T. Słownik mimiczny dla głuchoniemych i osób z nimi styczność mających [A mimical dictionary for the deaf-mute and those interacting with them] (Instytut Głuchoniemych i Ociemniałych, 1879).

Tomaszewski, P. & Sak, M. Is it possible to educate deaf children bilingually in Poland? In Zweisprachigkeit und Bilingualer Unterricht [Bilingualism and bilingual education] (eds. Olpińska-Szkiełko, M. & Bertelle, L.) 129–149 (Peter Lang Edition, 2014).

Zajkowska, M. & Swoi Inni, gdy głusi. Praktyki kolonizatorskie wobec głuchych w polsce [Part of us is Polish. Different if deaf. Colonizing practices towards the deaf in Poland]. Prz Hum. 5, 97–106 (2014).

Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych [Internet system of legal acts]. Ustawa z dnia 19 sierpnia 2011 r. o języku migowym i innych środkach komunikowania się [Act of 19 August 2011 on Sign Language and Other Means of Communication]. Accessed 15 Dec https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20112091243 (2024).

Tomaszewski, P., Wieczorek, R., Krzysztofiak, P. & Kowalska, J. Percepcja Audyzmu w Polskiej społeczności głuchych [Perception of audism in the Polish deaf community]. Societas/Communitas 2–2, 109–139 (2018).

Crawford, C., Sangermano, L. & Trinh, N-H-T. Oxford University Press,. Minority stress theory and internalized prejudice: Links to clinical psychiatric practice. In Sociocultural Issues in Psychiatry: A Casebook and Curriculum (eds. Trinh, N-H.T. & Chen, J.A.) 103–125 (2019).

Meyer, L. H. Minority stress and mental illness in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 36, 38–56 (1995).

Paradies, Y. et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 10, e0138511 (2015).

Alsubaie, M. M., Stain, H. J., Webster, L. A. D. & Wadman, R. The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth. 24, 484–496 (2019).

Garthe, K., Dingley, C. E. & Johnson, M. J. A historical and contemporary literature review of rejection sensitivity in marginalized populations. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 13 https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol13/iss1/1 (2020).

Kim, H., Han, K. & Won, S. Perceived discrimination as a critical factor affecting self-esteem, satisfaction with physical appearance, and depression of racial/ethnic minority adolescents in Korea. Behav. Sci. 13, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040343 (2023).

Gale, M. M. et al. A meta-analysis of the relationship between internalized racial oppression and health-related outcomes. Couns. Psychol. 48, 498–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020904454 (2020).

Brown, T. N., Sellers, S. L. & Gomez, J. P. The relationship between internalization and self-esteem among black adults. Sociol. Focus. 35, 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2002.10571220 (2002).

Szymanski, D. M. & Gupta, A. Examining the relationship between multiple internalized oppressions and African American lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning persons’ self-esteem and psychological distress. J. Couns. Psychol. 56, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015407 (2009).

Sosoo, E. E., Bernard, D. L. & Neblett, E. W. Jr. The influence of internalized racism on the relationship between discrimination and anxiety. Cultur Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 26, 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000320 (2020).

Frost, D. M. & Meyer, I. H. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. J. Couns. Psychol. 56, 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012844 (2009).

James, D. Internalized racism and past-year major depressive disorder among African-Americans: the role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 4, 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0269-1 (2017).

Molina, K. M. & James, D. Discrimination, internalized racism, and depression: a comparative study of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. GPIR 19, 439–461 https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216641304 (2016).

Mouzon, D. M. & McLean, J. S. Internalized racism and mental health among African-Americans, US-born Caribbean Blacks, and foreign-born Caribbean Blacks. Ethn. Health. 22, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2016.1196652 (2017).

Pitman, G. E. Body image, compulsory heterosexuality, and internalized homophobia. J. Lesbian Stud. 4, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v03n04_17 (1999).

Drazdowski, T. K. et al. Structural equation modeling of the effects of racism, LGBTQ discrimination, and internalized oppression on illicit drug use in LGBTQ people of color. Drug Alcohol Depend. 159, 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.029 (2016).

Hahn, H. Antidiscrimination laws and social research on disability: The minority group perspective. Behav. Sci. Law 14, 41–59. (1996).

Black, P. A. & Glickman, N. S. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of north American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 11, 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enj042 (2006).

Brown, P. M. & Cornes, A. Mental health of deaf and hard-of-hearing adolescents: what the students say. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 20, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enu031 (2015).

Chapman, M. & Dammeyer, J. The significance of deaf identity for psychological well-being. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 22, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw073 (2017).

Fellinger, J., Holzinger, D. & Pollard, R. Q. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet 379, 1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61143-4 (2012).

Kushalnagar, P., Reesman, J., Holcomb, T. & Ryan, C. Prevalence of anxiety or depression in deaf adults. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 24, 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enz017 (2019).

Kvam, M. H., Loeb, M. & Tambs, K. Mental health in deaf adults: symptoms of anxiety and depression among hearing and deaf individuals. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 12, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl015 (2007).

Peñacoba, C., Garvi, D., Gómez, L. & Álvarez, A. Psychological well-being, emotional intelligence, and emotional symptoms in deaf adults. Am. Ann. Deaf. 165, 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2020.0029 (2020).

Sanfacon, K. et al. Cross-sectional analysis of medical conditions in the U.S. deaf transgender community. Transgend Health. 6, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0028 (2021).

Werngren-Elgström, M., Dehlin, O. & Iwarsson, S. A Swedish prevalence study of deaf people using sign language: a prerequisite for deaf studies. Disabil. Soc. 18, 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000052888 (2003).

Kobosko, J. Poczucie niepełnosprawności a percepcja siebie i objawy depresji u osób dorosłych z głuchotą postlingwalną korzystających z implantu ślimakowego [Perception of disability, self-perception, and symptoms of depression in adults with postlingual deafness using cochlear implants]. Now Audiofonol. 4, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.17431/894294 (2015).

Tomaszewski, P. & Krzysztofiak, P. Internalized oppression and deaf mental health – A pilot study. In The International Conference, The Life of a New Word, Audism: Practices, Areas of Knowledge, and Social Change (2019).

Maxwell-McCaw, D. & Zea, M. C. The deaf acculturation scale (DAS): development and validation of a 58-item measure. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 16, 325–342 (2011).

Łojek, E. & Stańczak, J. Inwentarz Depresji Becka® – Wydanie drugie [Beck Depression Inventory® – Second Edition]. (Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego, 2019).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Psychological Corporation, 1996).

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F. & Natalicio, D. S. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Int. J. Psychol. 5, 3–44 (1971).

Wrześniewski, K., Sosnowski, T. & Matusik, D. Inwentarz Stanu i Cechy Lęku STAI. Polska Adaptacja STAI [The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI. Polish Adaptation of the STAI] (Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego, 2002).

Knowles, K. A. & Olatunji, B. O. Specificity of trait anxiety in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis of the state-trait anxiety inventory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 82, 101928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101928 (2020).

Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 27, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd (2011).

Lai, K. & Green, S. B. The Problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivar. Behav. Res. 51 (2–3), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2015.1134306 (2016).

Stone, B. M. The ethical use of fit indices in structural equation modeling: recommendations for psychologists. Front. Psychol. 12, 783226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783226 (2021).

de Sá Junior, A. R. et al. Can gender and age impact on response pattern of depressive symptoms among college students? A differential item functioning analysis. Front. Psychiatry. 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00050 (2019).

Estrada, B., Delgado, C. & Beyebach, M. Beck Depression Inventory-II in Spanish sign Language. Int. J. Hisp Psychol. 3, 1–21 (2010).

Estrada, B. Beck Depression Inventory-II in Mexican sign Language: reliability and factorial data. Int. J. Ment Health Deaf. 2, 4–12 (2012).

Leigh, I. W. & Anthony-Tolbert, S. Reliability of the BDI-II with deaf persons. Rehabil Psychol. 46, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.46.2.19557 (2001).

Mishra, S. K. & Kulshrestha, P. A study of depression, anxiety and quality of life in hearing impaired and hearing population. Disabil. Impair. 34, 15–29 (2020).

Sanz, J., Perdigón, A. & Vázquez, C. Adaptación española del inventario para la depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 2. Propiedades psicométricas en población general. [Spanish adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II): psychometric properties in the general population]. Clín Salud. 14, 249–280 (2003). http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180617972001

Cieśla, K., Lewandowska, M. & Skarżyński, H. Health-related quality of life and mental distress in patients with partial deafness: preliminary findings. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 273, 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3713-7 (2016).

Palmer, C. G. et al. Deaf genetic testing and psychological well-being in deaf adults. J. Genet. Couns. 22, 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-013-9573-7 (2013).

Maletić-Sekulić, I., Petković, S., Dragutinović, N., Veselinović, I. & Jeličić, L. The effects of auditory amplification on subjective assessments of hearing impairment and anxiety in people with presbycusis. Serb Arch. Med. 147, 461–467. https://doi.org/10.2298/SARH190123067M (2019).

Fiske, A., Wetherell, J. L. & Gatz, M. Depression in older adults. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 5, 363–389. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621 (2009).

Young, A. et al. Introducing the READY study: DHH young people’s well-being and self-determination. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 28, 267–279 (2023).

Jóhannsdóttir, Á., Egilson, S. Þ. & Haraldsdóttir, F. Implications of internalized ableism for the health and wellbeing of disabled young people. Sociol. Health Illn. 44, 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13425 (2022).

Mousley, V. L. & Chaudoir, S. R. Deaf stigma: links between stigma and well-being among deaf emerging adults. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 23, 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eny018 (2018).

Humphries, T. et al. Language acquisition for deaf children: reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm Reduct. J. 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-9-16 (2012).

Bar-Haim, Y., Lemy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, J. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxiety and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 133, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 (2007).

Mitte, K. Memory bias for threatening information in anxiety and anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 134, 886–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013343 (2008).

Calvo, M. G. & Cano-Vindel, A. The nature of trait anxiety: cognitive and biological vulnerability. Eur. Psychol. 2, 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.2.4.301 (1997).

Willmann, M., Langlet, C., Hainaut, J. P. & Bolmont, B. The time course of autonomic parameters and muscle tension during recovery following a moderate cognitive stressor: dependency on trait anxiety level. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 84, 51–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.01.009 (2012).

Barlow, D. H., Sauer-Zavala, S., Carl, J. R., Bullis, J. R. & Ellard, K. K. The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: back to the future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2, 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613505532 (2014).

Avery, S. N., Clauss, J. A. & Blackford, J. U. The human BNST: functional role in anxiety and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol 41, 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.185 (2016).

Kühn, S., Schubert, F. & Gallinat, J. Structural correlates of trait anxiety: reduced thickness in medial orbitofrontal cortex accompanied by volume increase in nucleus accumbens. J. Affect. Disord. 134, 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.003 (2011).

Miskovich, T. A. et al. I. cortical gyrification patterns associated with trait anxiety. PLoS One. 11, e0149434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149434 (2016).

Bess, F. H. et al. Y. Salivary cortisol profiles of children with hearing loss. Ear Hear. 37, 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000256 (2016).

Anderson, M. L., Craig, W., Hall, K. S., Ziedonis, D. M. & W. C. & A pilot study of deaf trauma survivors’ experiences: early traumas unique to being deaf in a hearing world. J. Child. Adolesc. Trauma. 9, 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0111-2 (2016).

Johnson, P., Cawthon, S., Fink, B., Wendel, E. & Schoffstall, S. Trauma and resilience among deaf individuals. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 23, 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eny024 (2018).

Chandanabhumma, P. P. et al. Examining the differences of perceptions and experience with online health information accessibility between deaf and hearing individuals: a qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 122, 108169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2024.108169 (2024).

McKee, M. et al. Reframing our health care system for patients with hearing loss. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 65, 3633–3645. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00052 (2022).

Włodarczak, A. Głuchy pacjent. Wyzwania i potrzeby [The deaf patient: Challenges and Needs]. (Wydawnictwo Psychoskok, 2018).

Clark, M. D. et al. The importance of early sign language acquisition for deaf readers. Read. Writ. Q. 32, 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2013.878123 (2016).

Dłużniewska, A. Rozumienie tekstów literackich przez uczniów z uszkodzeniami słuchu [Understanding literary texts by students with hearing impairments] (Impuls,2021).

Rogers, K. D. et al. The British sign Language versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire, the generalized anxiety disorder 7-Item Scale, and the work and Social Adjustment Scale. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 18, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ens040 (2013).

Rogers, K. D., Marsden, A., Young, A. & Evans, C. The influence of mode of remote delivery on health-related quality of life outcome measures in British sign Language: a mixed methods pilot randomised crossover trial. Qual. Life Res. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03864-0 (2024).

Fisher, R. & Boer, D. What is more important for national well-being: money or autonomy? A meta-analysis of well-being, burnout, and anxiety across 63 societies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 164–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023663 (2011).

10th anniversary of the adoption of Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/the-10th-anniversary-of-the-adoption-of-convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd-crpd-10.html ( Accessed 18 Aug 2024).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and & Medicine Disrupting Ableism and Advancing STEM: Promoting the Success of People with Disabilities in STEM Workforcehttps://doi.org/10.17226/27245 (National Academies, 2024).

National Science Foundation. Dear colleague letter: the social and behavioral science of bias, prejudice, and discrimination. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2024/nsf24052/nsf24052.jsp (Accessed 18 Aug 2024).

National Institutes of Health–National Institute of General Medical Studies. Enhancing the diversity of the NIH-funded workforce. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/training/dpc (Accessed 18 Aug 2024).

Biuro Pełnomocnika Rządu do Spraw Osób Niepełnosprawnych [Office of the Government Plenipotentiary for Disabled People]. The government plenipotentiary for disabledpPeople. https://niepelnosprawni.gov.pl/p,133,the-government-plenipotentiary-for-disabled-people (Accessed 15 Dec 2024).

Biuro Pełnomocnika Rządu do Spraw Osób Niepełnosprawnych [Office of the Government Plenipotentiary for Disabled People]. Polska Rada Języka Migowego [Polish Board of Sign Language]. https://niepelnosprawni.gov.pl/p,91,polska-rada-jezyka-migowego (Accessed 15 Dec 2024).

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, from funds awarded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the form of a subsidy for the maintenance and development of research potential in 2024(501-D125-01-1250000 zlec. 5011000614) and co-financed from the funds of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education "Excellence Initiative - Research University (2020-2026)" for the University of Warsaw. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PT: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, writing – original draft preparation, and funding acquisition; PK: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, writing – original draft preparation, and literature review; JK: data analysis, writing—review and editing; PH: data analysis, writing—review and editing, literature review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomaszewski, P., Krzysztofiak, P., Kowalska, J. et al. Internalized oppression and deaf people’s mental health. Sci Rep 15, 5268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89789-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89789-1