Abstract

Myasthenia gravis (MG) poses diagnostic challenges due to its diverse clinical presentations. Diagnosing MG remains complex despite advancements, necessitating further understanding of its diverse clinical profiles. We conducted a retrospective analysis of 290 MG cases. Patient demographics, symptomatology, and diagnostic outcomes were reviewed. Patients were categorized into two groups: those displaying classical presentations and those manifesting unusual presentations. The patients with unusual presentations were comprehensively evaluated and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups were compared. In our study of 290 patients with MG, 20 presented with unusual manifestations (6.9%). These included isolated dropped head, bilateral facial weakness, distal limb weakness (e.g., foot and hand drop), weakness of limb-girdle muscles, and isolated ocular findings without ptosis. When patients were categorized into two groups based on their initial symptoms, no significant differences in demographic and clinical features were observed between the classical and unusual groups, except for a higher prevalence of anti-MuSK antibodies and more frequent administration of rituximab in patients with unusual presentations. Recognizing unusual MG presentations is crucial for timely management. Our study underscores the diverse clinical spectrum of MG, emphasizing the need for nuanced diagnostic approaches and prompt intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diagnosing myasthenia gravis (MG) typically involves assessing the clinical profile, specific autoantibodies, and electrodiagnostic tests (repetitive nerve stimulation and single-fiber electromyography). Fatigable muscle weakness, exacerbated by activity and partly relieved by rest, constitutes the primary clinical feature of MG. Predominantly, initial symptoms manifest in the ocular region, often presenting as double vision and ptosis.

Despite significant advancements in understanding both clinical and pathophysiological aspects of MG, diagnosing MG can still pose challenges due to its often unusual clinical presentations. Unusual clinical features can include isolated weakness in facial muscles, limbs, or the neck, mimicking other neurological or myopathic conditions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. MG can also manifest with respiratory difficulties or unusual ocular findings, further complicating diagnosis9,10.

While accumulating knowledge about these clinical characteristics has significantly improved the diagnosis of MG, there is still insufficient data on the prevalence and characteristics of these unusual presentations. The literature consists mostly of case reports or brief descriptions within series focused on MG1,2,5,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. We aimed to systematically define the clinical and laboratory characteristics of MG patients with unusual presentations in a large single-center series of deeply phenotyped patients.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed patient records from our tertiary neuromuscular center, focusing on individuals diagnosed with myasthenia gravis between 2010 and 2023. The diagnosis of MG relied on a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria. Inclusion criteria included fluctuating muscle weakness along with the following findings:

-

(1)

Positive results on the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) or muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) antibody assay;

-

(2)

More than a 10% decrease in the compound muscle action potential amplitude during repetitive nerve stimulation;

-

(3)

Finding increased jitter on single-fiber electromyography (SFEMG);

-

(4)

Exclusion of alternative diagnosis.

Definite MG is diagnosed if two of the criteria 1, 2, or 3 and criterion 4 are fulfilled. Patients with onset before 18 years of age were excluded from the study. Additionally, we excluded patients who were lost to follow-up or for whom relevant information was missing.

Demographic and historical data were extracted from institutional electronic records, encompassing details such as age at the initial visit and symptom onset, gender, the specialty of the diagnosing physician, symptoms and signs suggestive of MG, antibody, and electrophysiological testing results.

Patients were categorized into two groups: those displaying classical presentations and those manifesting unusual presentations. Patients displaying classical presentations, such as ocular muscle involvement characterized by eyelid ptosis, fluctuating diplopia, or a combination of both, as well as those manifesting classical bulbar symptoms like dysarthria, dysphagia, and dysphonia, were categorized as exhibiting classical presentations. Conversely, unusual presentations at onset, such as isolated dropped head, bilateral facial weakness, distal limb weakness (e.g., foot and hand drop), and weakness of limb girdle muscles, isolated ocular findings without ptosis were classified as having unusual onset symptoms. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of these patients to delve deeper into factors such as diagnostic delays, the initial healthcare providers consulted, the number of healthcare professionals seen before the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis.

The local ethics committee approved the study (Bursa Uludag University, Uludag Faculty of Medicine, number 2023-27/34). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s), and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York, USA) 28.0 software was used for statistical evaluations, and p < 0.05 was accepted as the limit of significance. The chi-square test was performed for categorical variables. For group comparisons, Mann–Whitney U Test and Fisher’s exact tests were used where appropriate.

Results

A total of 16 patients were excluded from the initial cohort of 339 patients due to failure to meet inclusion criteria. Additionally, 33 patients were excluded due to the irrelevance of their data. Consequently, the study enrolled a total of 290 patients, consisting of 270 with classical presentations and 20 with unusual onset, as depicted in Fig. 1. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients.

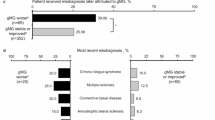

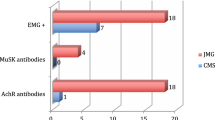

Serum antibody assays revealed anti-AChR antibody seropositivity in 223 patients, anti- MuSK antibodies in 15 patients, and double seronegativity in the remaining 52 patients. Among the 290 patients, 20 presented with unusual presentations (Fig. 2). Specifically, five patients exhibited dropped head, with one reporting concurrent hiccups. No other bulbar symptoms were observed aside from dropped head. Moreover, four patients presented with a dropped hand, while one presented with dropped foot. Notably, five patients demonstrated proximal weakness coupled with respiratory difficulty, devoid of any associated ocular manifestations. Furthermore, two patients initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy were later identified to have facial diplegia. Additionally, two patients presented with pseudo 6th nerve palsy without ptosis, and one patient presented with pseudo internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) without ptosis. The details of these 20 patients are presented in Table 2.

MG patients were divided into two cohorts according to the presence or absence of unusual findings, and a comparative analysis of their features is shown in Table 3. There were no significant intergroup differences in sex, age at diagnosis, anti-AChR antibody seropositivity, comorbid disease, presence of thymoma, thymectomy, hospitalization in intensive care unit, and previous treatment. Anti-MuSK antibody seropositivity was statistically more frequently reported in patients with unusual presentations than in those with classical presentations (p = 0.014). Our study revealed a higher frequency of rituximab use in patients with unusual presentations of myasthenia gravis compared to those with classical presentations (p = 0.008).

Misdiagnosis

Among the 20 patients with unusual presentations, various misdiagnoses were encountered. For instance, patients were initially misdiagnosed with conditions such as diabetic cranial nerve palsy, myalgia, myopathy, radiculopathy, rheumatic disease, entrapment neuropathy, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, demyelinating disease, depressive disorder, and pulmonary embolism. These misdiagnoses were predominantly made in primary and secondary care hospitals or during consultations with non-neurology specialists, rather than in specialized neuromuscular centers. The limited access to advanced diagnostic expertise and tools in these settings likely contributed to the diagnostic challenges.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically evaluated the clinical and laboratory features of MG patients with unusual presentations in a large single-center series. Our findings highlight the diverse clinical spectrum of MG and emphasize the importance of considering unusual presentations in the differential diagnosis of muscle weakness.

Table 4 presents the typical and unusual presentations of myasthenia gravis, as outlined in the current literature1,2,5,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Typical manifestations of MG include ptosis, diplopia, and bulbar symptoms such as dysarthria, dysphagia, and dysphonia20,21. However, it is important to note that there is no universally agreed-upon consensus for unusual presentations of MG. The classification used in this study is based on expert consensus, clinical observations, and insights from previous case reports and studies, reflecting the variability in MG presentations observed across different clinical settings. Our study contributes to the ongoing discussion by highlighting the diverse presentations of MG, including several unusual manifestations that can be easily misdiagnosed as other conditions.

According to our analysis, unusual manifestations of MG account for approximately 6.9% of all MG cases. Our study found no significant differences in various factors between classical and unusual MG cases, including sex, age at diagnosis, anti-AChR antibody seropositivity, comorbidities, thymoma, thymectomy, and intensive care unit admissions. However, the prevalence of anti-MuSK antibody positivity was found to be higher in unusual MG cases, suggesting its potential utility in aiding diagnosis in such presentations. Additionally, rituximab use was more frequent in patients with unusual myasthenia gravis presentations than in typical cases. This could be related to the higher prevalence of anti-MuSK antibody positivity observed in these patients.

Previous studies suggest that 90% of MG patients experience ptosis, and within two years, around 50% of those with this ocular symptom progress to generalized MG11. It has been observed that ocular MG can present with unusual manifestations such as pseudo internuclear ophthalmoplegia, pseudo-6th nerve palsy, vertical deviation, esotropia, and vergence anomalies9,10. In our series, pseudo-sixth nerve palsy was identified in two patients, while one patient presented with pseudo-INO. Although some patients had accompanying eye movement abnormalities, those with ptosis were not considered unusual presentations, as the ptosis helped in the diagnostic process. Pure and isolated ocular phenotypes of anti-MuSK MG are rarely reported22. Nevertheless, the identification of Anti-MuSK antibody seropositivity in an MG patient with pseudo-6 nerve palsy in our cohort provides additional support to previous research, suggesting the potential presence of Anti-MuSK seropositivity in cases of ocular MG.

Facial paralysis is another rare finding in MG patients1,2,12,13,14. There are case reports and case series of patients presenting with facial paralysis associated with MG1,2,12,13,14. While facial paralysis may be bilateral in some MG cases and unilateral in others, our study identified two patients presenting with isolated facial diplegia, without exhibiting symptoms of ptosis and initially followed up for a period due to bilateral Bell’s palsy.

Isolated presentations of drop head, dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea in MG warrant thorough investigation due to their rarity and potential diagnostic challenges2,3,4,15,23,24. Drop head can result from various etiologies, encompassing both neuromuscular and non-neuromuscular conditions5. MG contributes to approximately 12.3% of cases of drop head cases6. A study demonstrated that head drop occurred in approximately 10% of MG cases over the course of the disease, with a significantly higher prevalence observed in elderly individuals compared to younger cohorts16. The majority of these cases tested positive for AChR antibodies, although there was one case of positivity for MuSK antibodies. It is worth mentioning that isolated head drop as an initial symptom in MG is uncommon, with only three cases identified among 508 MG patients in a retrospective study2. Isolated presentations of dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea in MG are rarely documented in literature. They typically emerge as isolated case reports, highlighting their unique clinical significance and the need for further investigation3,4,15. In our study, we observed five patients presenting with drop head. Among these five patients, three tested positive for MuSK antibodies, while two tested positive for AChR antibodies. None of the patients in our cohort exhibited isolated dysphagia, dysarthria, or isolated dyspnea. Notably, one patient demonstrated hiccups alongside head drop. The pathophysiology of hiccups remains unclear in MG. Hiccups involve complex neurological mechanisms, including both central and peripheral components. In MG, impaired neuromuscular transmission in the diaphragm may potentially trigger hiccups. Furthermore, in cases with bulbar involvement, dysfunction in respiratory rhythm regulation and swallowing may contribute to the onset of hiccups25.

In our study, a subset of MG patients (1.72%) presented with limb-girdle weakness without involvement of the ocular muscles. A previous study found that 3.8% of MG patients had persistent limb-girdle weakness without oculobulbar involvement19. This manifestation often complicates diagnosis as MG may not be considered initially due to the absence of oculobulbar weakness. Furthermore, the predominant proximal muscle weakness, adult onset, and myogenic changes observed in needle electromyography contribute to misdiagnoses, with some patients being incorrectly labeled as having polymyositis despite normal creatine kinase (CK) levels. Genetic myopathies, such as muscular dystrophies, can also complicate the diagnostic process, as they may present with similar symptoms and, in some cases, co-occur with MG, further complicating the diagnosis26. The diagnosis of MG was confirmed through antibody tests and neurophysiological studies. Neurophysiological techniques, including repetitive nerve stimulation and single-fiber electromyography, provide definitive evidence of neuromuscular transmission deficits, especially in seronegative cases27. In cases where proximal weakness is prominent in the lower extremities, Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) becomes a notable differential diagnosis23. However, ruling out LEMS is facilitated by the absence of a compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude increase exceeding 100% during high-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation, in addition to antibody tests28.

Another rare presentation of MG is distal MG8. Consistent with previous studies, our study revealed that the upper extremity extensor muscles are the most frequently affected muscles in distal MG. Distal muscle weakness may occur not only throughout the course of the disease but also as an initial presentation of MG2,29. While the exact mechanisms for distal muscle involvement remain unclear, it may be hypothesized that certain muscle groups in some patients exhibit differential susceptibility to autoimmune attack. Additionally, antibody subtype and epitope heterogeneity may contribute to the increased susceptibility of extremity muscles in distal MG. This hypothesis requires further investigation in future studies. Another consideration is the potential association of myositis with MG30. However, the normal CK levels observed in our patients do not support this association.

Fluctuations were noted in both unusual and classical presentations of MG patients, and this variability was evident when examined within each group. Some individuals in both categories displayed less prominent fluctuations. However, a thorough analysis of fluctuations was not undertaken.

Additionally, compared to healthy individuals, comorbidities are more prevalent in MG patients, which can complicate the diagnostic process31. In typical MG presentations, comorbidities may mask or mimic the clinical symptoms of MG, thereby increasing diagnostic difficulty. Moreover, in atypical presentations, where symptoms deviate from the classical pattern, the presence of comorbidities exacerbates the challenges in establishing an accurate diagnosis.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, which may introduce bias into the findings. Additionally, the data was collected from a single tertiary center, which may restrict the generalizability of the results. Diagnostic delay was not systematically assessed in all patients. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information about the unusual clinical features and outcomes of patients with MG. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the clinical features of MG patients with unusual presentations. We emphasize the importance of considering unusual presentations in the differential diagnosis of muscle weakness and the need for early diagnosis and treatment to improve patient outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due general data protection policy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cucurachi, L., Cattaneo, L., Gemignani, F. & Pavesi, G. Late onset generalized myasthenia gravis presenting with facial weakness and bulbar signs without extraocular muscle involvement. Neurol. Sci. 30, 343–344 (2009).

Rodolico, C. et al. Myasthenia gravis: Unusual presentations and diagnostic pitfalls. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 3, 413–418 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Isolated dysarthria as the sole manifestation of myasthenia gravis: A case report. J. Int. Med. Res. 50, 03000605221109395 (2022).

Shiozumi, T., Okada, N., Matsuyama, T., Yamahata, Y. & Ohta, B. Anti-muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) antibody-positive myasthenia gravis presenting with dyspnea in an elderly woman: A case report. Cureus 15, e50480 (2023).

Brodell, J. D. Jr et al. Dropped head syndrome: An update on etiology and surgical management. JBJS Rev. 8, e0068 (2020).

Drain, J. P., Virk, S. S., Jain, N. & Yu, E. Dropped head syndrome: A systematic review. Clin. Spine Surg. 32, 423–429 (2019).

Yuksel, G., Gencer, M., Orken, C., Tutkavul, K. & Tireli, H. Limb girdle myasthenia. Neurosciences (Ryadh) 14, 184–185 (2009).

de Carvalho, M. & Geraldes, R. Longstanding right-hand weakness in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 34, 670–671 (2006).

Munasinghe, K., Herath, W., Silva, F. & Silva, S. A case report on Pseudo-Internuclear ophthalmoplegia: A rare manifestation of myasthenia gravis. Cureus 15, e46788 (2023).

Colavito, J., Cooper, J. & Ciuffreda, K. J. Non-ptotic ocular myasthenia gravis: A common presentation of an uncommon disease. Optometry 76, 363–375 (2005).

Kupersmith, M. J., Latkany, R. & Homel, P. Development of generalized disease at 2 years in patients with ocular myasthenia gravis. Arch. Neurol. 60, 243–248 (2003).

Kini, P. G. Juvenile myasthenia gravis with predominant facial weakness in a 7-year-old Boy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 32, 167–169 (1995).

Umair, M., Faheem, F., Malik, H. A., Hassan, S. A. A. & Iqbal, A. Bilateral facial palsy without ocular muscle involvement in myasthenia gravis: Case report. Cureus 14, e23210 (2022).

Kang, C-H., Kim, H. J., Oh, J-H. & Kang, S-Y. Myasthenia gravis presenting with facial diplegia without ocular muscle involvement. Kor. J. Commun. Nutr. 17, 35–37 (2015).

Khan, A. A. et al. A diagnostic dilemma of dysphonia: A case report on laryngeal myasthenia gravis. Cureus 13, e16878 (2021).

Sih, M., Soliven, B., Mathenia, N., Jacobsen, J. & Rezania, K. Head-drop: A frequent feature of late‐onset myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 56, 441–444 (2017).

Engel, A. G. Light on limb-girdle myasthenia. Brain 129, 1938–1939 (2006).

Vecchio, D., Varrasi, C., Comi, C., Ripellino, P. & Cantello, R. A patient with autoimmune limb-girdle myasthenia, and a brief review of this treatable condition. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 158, 53–55 (2017).

Oh, S. J. & Kuruoglu, R. Chronic limb-girdle myasthenia gravis. Neurology 42, 1153–1156 (1992).

Ricciardi, D., Todisco, V., Tedeschi, G. & Cirillo, G. Anti-MuSK ocular myasthenia with extrinsic ocular muscle atrophy: A new clinical phenotype? Neurol. Sci. 41, 221–223 (2020).

Balistreri, C. R., Vinciguerra, C., Magro, D., Di Stefano, V. & Monastero, R. Towards personalized management of myasthenia gravis phenotypes: From the role of multi-omics to the emerging biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Autoimmun. Rev. 23, 103669 (2024).

Gilhus, N. E. & Verschuuren, J. J. Myasthenia gravis: Subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 14, 1023–1036 (2015).

D’Amelio, M. et al. Dropped head as an unusual presenting sign of myasthenia gravis. Neurol. Sci. 28, 104–106 (2007).

Tamai, M. et al. Treatment of myasthenia gravis with dropped head: A report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Neuromuscul. Disord. 25, 429–431 (2015).

Rouse, S. & Wodziak, M. Intractable hiccups. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 18, 51 (2018).

Avallone, A. R. et al. AChR-seropositive myasthenia gravis in muscular dystrophy: Diagnostic pitfalls and clinical management challenges. Neurol. Sci. 46, 125–132 (2025).

Vinciguerra, C. et al. Diagnosis and management of seronegative myasthenia gravis: Lights and shadows. Brain Sci. 13, 1286 (2023).

Wirtz, P. et al. The difference in distribution of muscle weakness between myasthenia gravis and the Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 73, 766–768 (2002).

Werner, P., Kiechl, S., Löscher, W., Poewe, W. & Willeit, J. Distal myasthenia gravis–frequency and clinical course in a large prospective series. Acta Neurol. Scand. 108, 209–211 (2003).

Garibaldi, M. et al. Muscle involvement in myasthenia gravis: Expanding the clinical spectrum of Myasthenia-Myositis association from a large cohort of patients. Autoimmun. Rev. 19, 102498 (2020).

Di Stefano, V. et al. Comorbidity in myasthenia gravis: multicentric, hospital-based, and controlled study of 178 Italian patients. Neurol. Sci. 45, 3481–3494 (2024).

Acknowledgements

none.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EOA-SEL—GG Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. YD-FD Formal analysis, Data curation. Necdet Karli: Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oguz-Akarsu, E., Lazrak, S., Gullu, G. et al. Unusual presentations of myasthenia gravis and misdiagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 7516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91470-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91470-6