Abstract

Despite progress in contraceptive use, Ethiopia faces significant challenges in adopting modern methods, particularly in pastoralist areas. Existing studies predominantly focus on women’s family planning (FP) service utilization, often overlooking couple-level outcomes and male perspectives. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring factors affecting modern contraceptive use among couples in the Fentale District of Eastern Ethiopia. This mixed-methods cross-sectional study collected qualitative data from August 1 to September 20, 2021, and quantitative data from October 1 to December 25, 2021. A total of 1496 married couples were sampled using multi-stage systematic sampling. Quantitative data were gathered via semi-structured questionnaires, while qualitative data were obtained from 10 focus group discussions (FGDs), 20 key informant interviews (KIIs), and 30 in-depth interviews (IIDs). Quantitative analysis employed multivariable logistic regression modeling, and qualitative data were analyzed thematically without computer software. Among participants, 46.3% married at age 15 or younger, 53.8% lacked formal education, and 64.6% were nomadic pastoralists. Notably, 94.2% never discussed family planning, and only 27.4% used any form of family planning, with 18.2% opting for modern methods. Short-term methods like pills (13.7%), injectables (5.9%), and male condoms (7.5%) were more prevalent than traditional methods (9.0%) or long-term methods (1.6%). Concerns included a desire for more children (68.7%), religious opposition (63.0%), partner opposition (51.1%), and fear of side effects (42.9%). Early marriage (AOR = 0.613, 95% CI 0.315–1.193) and no formal education (AOR = 2.878, 95% CI 1.976–4.191) decreased contraceptive use odds, while being in business increased odds (AOR = 7.461, 95% CI 3.324–16.748). Mobile phone ownership increased use odds (AOR = 3.628, 95% CI 1.573–8.363), while having a bank account decreased odds (AOR = 0.017, 95% CI 0.006–0.045). Discussing family planning significantly increased contraceptive use odds (AOR = 15.708, 95% CI 2.320-106.369), while desiring more children decreased odds (AOR = 0.406, 95% CI 0.185–0.890). These findings underscore the importance of socio-demographic, socio-economic, reproductive history factors, spousal communication, and male involvement in modern contraceptive use among pastoralist communities. The study reveals unique reproductive challenges faced by pastoralist couples, driven by socio-demographic, socio-economic, reproductive history factors, and cultural beliefs that impact modern contraceptive use. Tailored interventions, including promotion of long-term contraceptive methods, educational campaigns involving religious leaders, and mobile health services, are essential to address limited healthcare access. Engaging both spouses in family planning, promoting male involvement, and fostering joint decision-making through effective communication are crucial for enhancing contraceptive uptake and improving reproductive health outcomes. Collaboration with community members and stakeholders is vital for the success of targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of modern contraceptive methods is crucial for enhancing reproductive health and promoting effective family planning across various cultural contexts. However, in pastoralist communities, specific cultural norms and practices play a significant role in influencing the acceptance and utilization of these methods. These communities often face unique challenges in accessing family planning services due to traditional beliefs, socio-economic constraints, and limited engagement in family planning discussions1.

Understanding these dynamics is particularly important in the Fentale District of Eastern Ethiopia, where cultural practices, socio-demographic factors, and reproductive history shape reproductive behaviors. While previous research has largely focused on women’s perspectives, less emphasis has been placed on couple-level outcomes and the role of male involvement in family planning decisions. Key reproductive history factors, such as age at first marriage and desire for future children, may also significantly influence modern contraceptive utilization, but they are often overlooked in existing literature. This gap limits the development of interventions tailored to the specific needs of pastoralist communities2. To address this gap, the present study explores the factors affecting modern contraceptive use among couples in the Fentale District.

By examining the specific barriers that pastoralist couples face in accessing and utilizing family planning services, this research aims to contribute to the development of targeted interventions that enhance reproductive health. The findings are expected to provide a deeper understanding of the challenges in pastoralist settings and to inform strategies for improving family planning services to better meet the needs of these communities1.

The Fentale District in Eastern Ethiopia is characterized by a nomadic lifestyle and agro-pastoralism, which influence the local economy and social structure. These pastoralist communities encounter unique challenges in accessing essential services, particularly healthcare, due to their mobility and limited infrastructure3. Family planning services are often concentrated in a few health facilities, requiring long journeys that can take hours or even days4.

Despite national progress in contraceptive use, significant barriers persist in pastoralist areas, where traditional beliefs and practices can hinder effective family planning5. Most research has centered on women’s use of family planning services, often overlooking men’s perspectives and the dynamics of decision-making within couples6. This study aims to fill this gap by addressing the following research questions:

-

1.

What is the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married couples in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District?

-

2.

What are the socio-economic, socio-demographic, and reproductive history predictors of modern contraceptive utilization among married couples in the Fentale District?

-

3.

How does couple communication impact family planning discussions and the adoption of contraceptive methods?

-

4.

What are the barriers to modern contraceptive use identified by married couples in the Fentale District?

-

5.

What role does male involvement play in family planning discussions and decisions regarding contraceptive use among couples?

The general objective of this study is to explore the factors influencing modern contraceptive use among married couples in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia. The specific objectives include:

-

Identifying the prevalence of modern contraceptive use.

-

Analyzing the socio-demographic, socio-economic, and reproductive history factors (e.g., age at first marriage, desire for future children) that influence utilization.

-

Exploring the role of couple communication in family planning decisions.

-

Assessing barriers to the adoption of modern contraceptives.

-

Providing recommendations for culturally sensitive interventions.

This research is significant for several reasons. By focusing on the factors that influence modern contraceptive use among married couples, it addresses a major gap in the literature, which has largely concentrated on women’s use of family planning services7. Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of couple-level dynamics and male perspectives, offering a more comprehensive understanding of family planning behavior8. The findings will inform the development of culturally sensitive intervention strategies that consider the unique socio-demographic and cultural contexts of pastoralist communities, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of family planning programs9.

Additionally, by identifying barriers to contraceptive use and promoting male involvement in family planning discussions, this study aims to improve reproductive health outcomes in the Fentale District. This is particularly critical given the high maternal and child mortality rates often linked to inadequate family planning services10. Addressing challenges such as traditional gender roles and limited awareness of the benefits of family planning will be key to fostering a supportive environment for reproductive health. Efforts to increase male support can include targeted educational programs, community workshops, and initiatives that promote spousal communication about family planning decisions11.

Metrics for evaluating success in this study will include the prevalence of modern contraceptive use, frequency of couple communications on family planning, and changes in attitudes toward contraceptive use among men and women. By establishing clear indicators of success, the research aims to provide actionable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers12.

In conclusion, this study is not only valuable for deepening the understanding of family planning dynamics within pastoralist communities but also for improving reproductive health services and outcomes in the Fentale District and similar settings. By focusing on male engagement and measuring success through well-defined metrics, this research aims to guide the development of targeted interventions that address the unique challenges faced by these communities, contributing to improved reproductive health2.

Methodology

Study design

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative research methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of modern contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District. This approach facilitated a robust exploration of the complex factors influencing contraceptive behaviors by combining numerical data with rich, contextual insights.

Quantitative component

The quantitative component involved a cross-sectional survey designed to gather standardized data from a representative sample of married couples. The survey assessed the following key areas:

Demographic information

Participants provided data on age, education level, occupation, income, and duration of marriage13.

Knowledge and awareness

The survey evaluated participants’ awareness of modern contraceptive methods, including their effectiveness and accessibility14.

Current use of contraceptives

Information was collected regarding whether couples were currently using any form of contraception, the methods chosen, and reasons for use or non-use15.

Couple communication

Questions explored the frequency and nature of discussions between partners regarding family planning and contraceptive use16.

Cultural and social influences

Assessments focused on beliefs and attitudes toward family planning, including perceived societal norms and barriers17.

Economic influences

The survey examined the impact of economic factors, such as household income, access to resources (including mobile phones), and financial literacy on contraceptive use18. The role of mobile phones in accessing health information, facilitating communication about family planning, and connecting with healthcare services was particularly emphasized19.

Reproductive history influences

Participants were asked about their reproductive history, including the number of children already born, desire for future children, and timing of pregnancies20. Understanding couples’ motivations for having additional children provided insights into their contraceptive choices and family planning decisions21. This quantitative data enabled the identification of trends, relationships, and potential predictors of contraceptive use among married couples.

Qualitative component

The qualitative component consisted of focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews, providing a deeper understanding of the social and cultural dynamics surrounding contraceptive use in pastoralist communities22. This component focused on:

Focus group discussions (FGDs)

Separate groups of men and women engaged in discussions facilitated by trained moderators23. These discussions explored community perceptions of family planning, gender roles in decision-making, and the influence of cultural beliefs on contraceptive practices24. Each FGD consisted of 6–10 participants, allowing for diverse perspectives while fostering an environment for open dialogue25.

In-depth interviews

Key informants, including community leaders, health workers, and knowledgeable individuals in the field of reproductive health, were interviewed26. These interviews provided insights into community attitudes, barriers to accessing family planning services, and recommendations for improving reproductive health initiatives26. The interviews were semi-structured, allowing for flexibility in exploring topics that emerged during the conversation27.

Rationale for mixed-methods approach

Utilizing a mixed-methods approach enhanced the study’s validity and depth by:

Complementing quantitative findings

Qualitative data helped contextualize and explain patterns observed in the quantitative results, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of contraceptive use28.

Qualitative methods uncovered the cultural, social, and emotional factors that influenced decision-making regarding family planning, which are often overlooked in purely quantitative studies22. This approach provided a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding contraceptive use, highlighting the importance of considering these factors when developing interventions aimed at improving family planning practices. By integrating qualitative insights with quantitative data, the study was able to offer a more nuanced perspective on the barriers and facilitators of contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District22.

Developing culturally relevant interventions

Insights gained from both components informed the development of culturally sensitive interventions aimed at increasing contraceptive uptake and improving reproductive health outcomes29.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring informed consent from all participants30. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty was emphasized31. Approval from relevant ethical review boards was obtained prior to data collection32.

Study setting

The research was conducted in the Fentale District, located in Eastern Ethiopia. This district is characterized by its pastoralist communities, where the lifestyle and socio-cultural dynamics significantly influence reproductive health behaviors. Pastoralism in Ethiopia embodies both a cultural heritage and a livelihood system deeply entrenched in vast rangelands. This lifestyle is particularly prominent in underdeveloped regions with limited social services and infrastructure, serving as a vital production system in arid and semi-arid areas2. The distinction between pastoralism and agro-pastoralism lies in their primary sources of income: pastoralists primarily rely on livestock and their by-products, whereas agro-pastoralists combine cultivation with a lesser emphasis on livestock rearing33.

Challenges faced by pastoral communities include rapid population growth, prolonged resource conflicts, and constrained access to grazing areas and water sources. These obstacles are often exacerbated by the effects of climate change and the prevalence of livestock diseases33.

This research was conducted in Fentale Woreda, located within the East Showa Zone of the Oromia regional state in Ethiopia, specifically in the southern part of the northern rift valley. The geographical landscape is characterized by a nomadic lifestyle and agro-pastoralism, along with distinctive seasonal migration patterns typical of pastoralist populations. The local economy is primarily centered on livestock production, which serves as a crucial pillar for the community, as detailed in our previous study2.

Fentale District comprises 20 kebeles, including 18 rural and 2 urban administration kebeles, with 15 specifically designated as pastoralist kebeles. The pastoralist kebeles selected for this study include Kobo, Benti, Gola, Dhaga Edu, Tututi, Ilalla, and Gelcha. The healthcare infrastructure in the district consists of four health centers, each village hosting a health post, and an additional health center located in Metehara City. There is also a hospital that primarily serves non-pastoralists and the staff of the Metehara sugar factory2.

Family planning services are primarily provided at the Metehara Hospital and Health Center. Although health posts exist in each kebele, their capacity to offer comprehensive family planning (FP) services is limited due to supply chain issues and a shortage of trained personnel. Furthermore, mobile social services, such as mobile health clinics and trained personnel, are lacking, as reported by local respondents and health workers [unpublished]. This situation poses significant challenges for the pastoralist community, particularly due to the lack of direct transportation options, necessitating long travel times to access care34.

Accessing healthcare services often requires arduous journeys that can take hours or even a full day of walking, leading to substantial delays for pastoralists waiting for transportation, which can extend up to a week. Staffing at the health centers is predominantly composed of nurses, with Health Extension Workers (HEWs) managing health posts. Traditional birth attendants, locally known as “Deesisttu Aadaa,” play a pivotal role in assisting women during childbirth and are held in high regard within the community.

The social, economic, and cultural dimensions of the study area intricately contribute to its unique context, shaping the backdrop against which this research unfolded. For a more detailed exploration of these aspects, please refer to our comprehensive description2.

Study population

This study was conducted among the pastoralist community residing in Fentale Woreda, East Showa Zone of Oromia Regional State, and Ethiopia. The target population included married couples selected for their unique characteristics, as pastoralist communities are known for their nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle, which revolves around livestock herding and seasonal migration in search of pasture and water.

To ensure the sample’s relevance and representativeness, this study implemented specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants included married women aged 15–49 years and their husbands, with eligibility limited to non-pregnant women. Legally married couples who had lived in the village or mobile areas for at least one year due to pastoral migration were considered. Additionally, couples cohabiting in the study area or mobile regions, as well as those intending to remain in the district or mobile areas for at least one year and six months from the start of data collection, were included. Husbands were required to consent to their wives’ participation, and both partners had to be mentally capable of providing informed consent. The study only considered monogamous marriages, and for wives under 18, written consent was obtained from their husbands, in accordance with cultural norms and ethical guidelines.

Exclusion criteria were applied to married women and their husbands outside the 15–49 age range, couples where either partner declined participation, and couples with mental incapacities. The study also excluded husbands in polygamous marriages, pregnant women and their husbands, couples who had not lived in the village or mobile areas for at least one year, couples not cohabiting in the same household, and those who did not plan to remain in the district for at least 18 months from the data collection period. Specifically, husbands in polygamous marriages (those with more than one wife) were excluded to avoid redundancy, as their responses could disproportionately influence the data compared to those from monogamous unions. These inclusion and exclusion criteria ensured that the study focused on a relevant and representative sample from the pastoralist community, thus improving the validity and reliability of the findings. For more detailed information regarding the study population, please refer to our published work2.

Sample size determination

Sample size determination for quantitative analysis

The sample size was calculated using the single population formula, based on specific parameters outlined in a prior study conducted in the Afar region1. We carefully set a standard normal deviation (Z) at Zα/2 = 1.96 to achieve a 95% confidence level, with a power of 90%. Utilizing the estimated key proportion of current family planning utilization in the Oromia regional state (28.1% or 0.281) from the Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey (2016) report, we incorporated a desired precision of 0.05, making adjustments for finite population correction. Additionally, we applied an Intra-Cluster Correlation Coefficient (ICC) variation of 0.05 to account for clustering effects.

Initially, the calculated sample size was 310 couples. To accommodate potential loss to follow-up, we added a 20% increment, resulting in a revised total of 374 couples. This figure was then adjusted for clustering effects by applying a design effect of 2.2, leading to a final sample size of 748 couples.

This methodology facilitated the systematic selection of 748 couples per group, resulting in a cumulative sample size of 1496 individuals for the study. Systematic sampling was employed to select couples from the eligible population, ensuring a representative sample across different regions within the district. For a more detailed explanation of the Sample Size Determination for Quantitative Analysis, please refer to our published work2.

Sample size determination for qualitative analysis

For the qualitative component, the sample size was determined based on the principle of saturation, which involves continuing data collection until no new themes or insights emerge. A total of 10 focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with a range of key stakeholders. These discussions were organized to include 4 FGDs with women, 4 FGDs with men, and 2 FGDs with local leaders. In addition to the FGDs, 30 in-depth interviews (IDIs) were carried out with both users and non-users of family planning. Furthermore, 20 key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted, involving health extension workers, nurses, and family planning coordinators in the district.

This triangulation approach ensured the collection of diverse perspectives, thereby enriching the data and providing a comprehensive understanding of family planning practices within the pastoralist community1.

Sampling technique

A total of 1,496 married couples were sampled through multi-stage systematic sampling, ensuring that both partners were included in the assessment of family planning practices35 Quantitative data were collected using semi-structured questionnaires, which facilitated gathering information from both husbands and wives regarding their contraceptive use, socio-demographic factors, socio-economic status, reproductive health factors, barriers, knowledge (awareness), and attitudes towards family planning.

For the qualitative component, we employed non-probabilistic convenience sampling to select participants for focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and in-depth interviews. This approach allowed us to engage key stakeholders who could provide valuable insights into the barriers and facilitators of contraceptive use from both partners’ perspectives. By selecting participants based on their availability and willingness to participate, we enriched our data collection process, enabling us to capture a broad range of views and experiences regarding family planning.

This dual approach enabled us to explore the complexities of couple dynamics in decision-making related to family planning, as highlighted in our findings36.

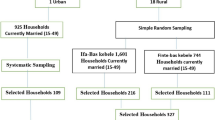

Figure 1 illustrates the multi-stage sampling strategy employed in this study2. Districts (woredas) served as primary sampling units (PSUs), while sub-districts (kebeles) functioned as secondary sampling units (SSUs). The Fentale District, located in the East Showa Zone, comprises 20 kebeles, including 18 rural and 2 urban administration kebeles. Initially, 15 pastoralist kebeles were purposively selected based on criteria such as accessibility, social structure, economic strength, and pastoralist characteristics. From these, seven kebeles were randomly chosen2.

Sample size allocation

The source population consisted of married couples, with women of reproductive age systematically sampled from each kebele37. This systematic sampling approach ensured representative selection, with villages chosen based on their proximity to health facilities to minimize variability. In the seven selected pastoralist sub-districts, there were 1,045 women of reproductive age and their husbands, totaling 2,090 married couples across 5,223 households.

Sample size allocation was proportional to the number of households in each kebele. Within each sub-district, married couples were selected for interviews at equal intervals using a systematic sampling technique. For a more detailed explanation of the Sample Size Allocation for Quantitative Analysis, please refer to our published work2.

Qualitative data collection involved non-probabilistic convenient sampling, with semi-structured thematic guides applied for in-depth interviews, Key informants interviews and focus group discussions10. These discussions aimed to understand the phenomena of couples’ utilization of family planning services and their determinants within society. In-depth interviews provided insights into barriers and underlying factors, with participants selected purposively based on their ability to provide relevant information38. Discussions were facilitated by trained moderators, with all sessions being recorded for accuracy39. These recordings were then transcribed, translated, and analyzed to derive insights40. The fieldwork for this couple-based mixed-methods cross-sectional study was conducted in two phases: qualitative data collection took place from August 1 to September 20, 2021, followed by quantitative data collection from October 1 to December 25, 202141.

Sample size allocation

The source population consisted of married couples, with women of reproductive age systematically sampled from each kebele37. This systematic sampling approach ensured representative selection, with villages chosen based on their proximity to health facilities to minimize variability. In the seven selected pastoralist sub-districts, there were 1,045 women of reproductive age and their husbands, totaling 2,090 married couples across 5,223 households.

Sample size allocation was proportional to the number of households in each kebele. Within each sub-district, married couples were selected for interviews at equal intervals using a systematic sampling technique. For a more detailed explanation of the Sample Size Allocation for Quantitative Analysis, please refer to our published work2.

Qualitative data collection involved non-probabilistic convenient sampling, with semi-structured thematic guides applied for in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions42. These discussions aimed to understand the phenomena of couples’ utilization of family planning services and their determinants within the society. In-depth interviews provided insights into barriers and underlying factors, with participants selected purposively based on their ability to provide relevant information43. Discussions were facilitated by trained moderators, with all sessions recorded for accuracy44. These recordings were then transcribed, translated, and analyzed to derive insights (Assumed Citation). The fieldwork for this couple-based mixed-methods cross-sectional study was conducted in two phases: qualitative data collection took place from August 1 to September 20, 2021, followed by quantitative data collection from October 1 to December 25, 202145.

Data collection approach

Data collection approach for quantitative data

A structured and pre-tested questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Oromiffa, followed by back-translation into English to ensure accuracy and consistency. Separate questionnaires were administered to male and female respondents, covering socio-demographic and economic factors, reproductive history, and knowledge and practices related to family planning (FP). The questionnaire gathered information on contraceptive ever-use, current use, reasons for non-use, types of contraceptives, knowledge of contraceptive methods, sources of family planning services, and potential side effects. These instruments were derived from validated questionnaires recognized for their reliability2,46,47,48.

Prior to the main data collection, a pre-test was conducted with 5% of the couples in a different district to assess the questionnaire’s validity and clarity. The data collection team comprised 15 male and 15 female data collectors, supervised by six locally recruited field coordinators. Male data collectors interviewed husbands, while female data collectors interviewed wives, ensuring sensitivity in discussing the topics2,41.

Individual interviews were conducted with each participant in private settings to ensure confidentiality, with locations chosen based on participant preference. Data collectors and supervisors underwent a six-day training session that covered study objectives, procedures, data collection techniques, and interviewing skills, addressing any concerns. The training included practical exercises, such as role-playing. Participants were provided with comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, ensuring informed consent was obtained.

Careful attention to consistency in questionnaire administration between genders helped ensure direct and accurate comparisons between responses.

Data collection approach for qualitative data

For the qualitative component, data collection involved in-depth interviews (IDIs), key informant interviews (KIIs), and focus group discussions (FGDs), all guided by a semi-structured topic guide. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of kebele administrators, district desk heads, supervisors, and the principal investigators, ensuring a thorough understanding of the study context.

To gather comprehensive insights, FGDs were conducted with various stakeholders, including women, husbands, health workers, and male local leaders. In addition, IDIs were carried out with both users and non-users of family planning methods, while KIIs involved health extension workers, nurses, and case team coordinators of family planning within the district. This multi-pronged approach allowed us to capture a wide range of perspectives and experiences related to family planning in the study area.

The key informant interviews were conducted in private settings to ensure confidentiality. Discussions were facilitated using a semi-structured topic guide, enabling an in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences and viewpoints on family planning. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed thematically, identifying key themes and insights related to contraceptive use and the challenges faced by the community.

Measurement of variables

The measurement of variables in this study involved several key components:

-

1.

Family Planning Utilization: This variable was assessed by asking participants about their contraceptive use during the data collection period, which corresponded to the 3-month baseline survey timeframe from October 1 to December 25, 2021. The primary outcome variable focused on the actual use of modern family planning methods, determined by the question: “Are you or your partner currently using any method to delay or prevent pregnancy?” Additionally, data on the specific types of modern family planning methods used (such as pills, Depo-Provera, condoms, Jadelle, Implanon, IUCD, etc.) were collected from both partners2,49.

-

2.

Socio-Demographic and Economic Variables: These were gathered using structured questionnaires administered separately to male and female respondents. The questionnaires captured various aspects, including reproductive history, family planning practices, reasons for non-use of contraceptives, and details on types of contraceptives49.

Measurement of independent variables—couple’s exposure to media

In the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey (EDHS), information on couples’ access to and exposure to media resources was collected by asking respondents about their frequency of listening to the radio, watching television, or reading newspapers/magazines. In the current analysis, couples’ exposure to media is defined as a binary variable, where a value of 1 indicates that at least one member of the couple in the household engages with any of the media sources—radio, television, or newspapers/magazines—at least once a week. To clarify and make these categories more meaningful, we define them as follows:

Less frequent

Exposure to media (newspapers, radio, and television) less than once a week.

More frequent

Exposure to media (newspapers, radio, television) at least once a week.

Qualitative data

In-depth interviews, key informant interviews (KIIs), and focus group discussions (FGDs) used a semi-structured topic guide to explore barriers to family planning. The qualitative data were analyzed thematically, with recordings transcribed, translated, and interpreted to derive insights38.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics characterized the study population and relevant variables, while bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identified predictors of contraceptive use. Statistical significance was set at p-values < 0.05, and multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance levels and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)50.

These measurement strategies provided a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing modern contraceptive use among the study population.

Data management and analysis approach

This study implemented rigorous procedures to ensure the accuracy and reliability of both quantitative and qualitative data. Responses were carefully reviewed for completeness by the principal investigator, and unique codes were assigned to facilitate data traceability. Data were transferred to statistical software packages, specifically SPSS version 23.0 and STATA version 14.0, for analysis.

Quantitative data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS and STATA by the principal investigator. Descriptive statistics, such as means, frequencies, and percentages, summarized the dataset and captured variable distributions. Pearson’s Chi-square test assessed the statistical significance of relationships between variables, focusing on socio-demographic factors, couple communication, and contraceptive use. Logistic regression evaluated associations between contraceptive use and predictor variables, including age, education, and marital status, adjusting for confounders to produce adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was conducted to assess multicollinearity among predictor variables, ensuring model validity. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and included in the multivariate models51.

Data management and analysis

Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics to characterize the study population and relevant variables, while bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to identify predictors of contraceptive use. Statistical significance was set at p-values < 0.05, and multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance levels and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)50. These measurement strategies provided a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing modern contraceptive use among the study population50.

Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data from Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), In-Depth Interviews (IDIs), and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were recorded, transcribed, and translated. The principal investigator led a systematic thematic content analysis using both manual coding and software like NVivo or ATLAS.ti. This analysis identified recurring themes related to family planning practices, barriers to contraceptive use, and socio-cultural influences. Multiple coding iterations refined the themes, with intercoder reliability established through collaboration with additional coders. Direct quotations from participants were integrated into the analysis to emphasize nuanced socio-cultural factors influencing contraceptive use.

Triangulation and consistency

To strengthen the findings, triangulation was employed to integrate results from both qualitative and quantitative data. Cross-referencing findings from various sources confirmed the reliability and validity of conclusions. This approach, overseen by the principal investigator, provided a holistic understanding of the factors influencing contraceptive use in the Fentale District.

Handling missing data

A systematic approach was used by the principal investigator to address missing data in the quantitative analysis. Techniques such as multiple imputation and case-wise deletion were applied depending on the nature of the missing data. Sensitivity analyses assessed the potential impact of missing data on study outcomes, ensuring robust results.

This comprehensive data management and analysis strategy, directed by the principal investigator, allowed for well-supported and reliable conclusions, offering valuable insights into the predictors and barriers of modern contraceptive use among married couples in the pastoralist communities of the Fentale District.

Ethical considerations

This study received approval for all protocols from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jimma University and the Oromia Regional Health Bureau prior to data collection. Ethical clearance was granted by the Institute of Health IRB at Jimma University (IHRPG-927/2020) and the Health Ethical Review Committee of the Oromia Regional Health Bureau (BEFO/HBTFH/999/2020). Formal consent was obtained from the Health Department of the Eastern Shewa Zone in the Oromia Regional State and the Fentale District within the Eastern Shewa Zone2.

Before participating, all respondents provided informed, voluntary, written, and signed consent after receiving a thorough explanation of the study’s objectives and procedures. This process ensured that participants were fully aware of their rights, including the option to withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty. The study strictly adhered to the core principles of human research ethics, including respect for individuals, beneficence, voluntary participation, confidentiality, and justice. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from spouses acting on behalf of wives under 18, following cultural norms and ethical guidelines. While no direct compensation was offered, participants were provided with information about available health services and resources, which served as an indirect benefit.

Data collected from participants were anonymized and stored securely to maintain confidentiality. Unique identifiers were used to separate each participant’s data from their personal information, ensuring that only authorized personnel had access to the data. The data were stored in locked cabinets and secure electronic files, and access was restricted through password-protection and encryption measures. Data will be retained for five years after the study’s completion, in line with institutional policies, after which all data will be securely destroyed to ensure participant confidentiality.

Potential risks to participants included emotional distress arising from discussions on sensitive topics during interviews. To mitigate these risks, researchers received extensive training on handling sensitive topics with care, and participants were informed about available support resources should they experience discomfort. The research team closely monitored the study process and gathered feedback from participants to promptly address any emerging concerns.

Data management practices included daily backups to ensure the preservation of the most current information. Backup copies were securely stored on both on-site servers and off-site cloud storage solutions, ensuring redundancy. All backup data were encrypted to maintain confidentiality, and access was restricted to authorized personnel. Regular audits and quarterly tests of data integrity ensured the recoverability of backups. Additionally, participants were informed about the data destruction process, ensuring transparency regarding data handling2.

Results

Table 1 highlight that a significant majority of couples (81.8%) do not use modern contraceptives, with various socio-demographic factors influencing this behavior. A higher proportion of non-users were found among couples where the wife married at or before the age of 15 (46.3%) and among those with no formal education (53.8%)1,52. additionally, religious affiliation played a role, with Muslims exhibiting a notably higher proportion of non-users (97.9%) compared to Christians (2.1%)52. These findings suggest that early marriage, lack of education, and religious factors are key barriers to modern contraceptive use in this population.

Access to resources, such as mobile phones and media exposure, also significantly impacted contraceptive use. Couples without these resources exhibited higher rates of non-utilization53. Moreover, the desire for more children emerged as a major factor contributing to non-use, highlighting the need for culturally sensitive family planning interventions tailored to the socio-economic context of pastoralist communities54.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing both socio-economic and cultural barriers to contraceptive access and education in order to improve reproductive health outcomes in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia2.

The study focused on family planning practices among married couples in the Fentale District’s pastoralist communities. Initially, 1,496 eligible married couples were identified, with 93.8% (1,404) participating in the cross-sectional survey. Challenges arose due to the nomadic lifestyle, which involved frequent relocations for livestock needs, as well as seasonal migration and district instability. However, proactive measures were implemented to mitigate these challenges2.

The socio-demographic data revealed that 46.3% of respondents were married at age 15 or younger, while 13.7% were married between the ages of 16–17, and 40.0% married at age 18 or older. The age distribution of respondents was as follows: 7.8% in the 15–19 years group, 21.9% in the 20–24 years group, 26.5% in the 25–29 years group, 19.9% in the 30–34 years group, 8.5% in the 35–39 years group, 8.3% in the 40–44 years group, and 7.1% were 45 years or older55. Regarding education, 53.8% of respondents had no formal education, 32.6% had primary education, and 13.5% had secondary education or higher56. The majority of respondents were Muslim (97.9%), with only 2.1% identifying as Christian. Furthermore, 99.6% of respondents belonged to the Oromo ethnic group57.

The socio-economic profile of the respondents showed that the majority (64.6%) were nomadic-pastoralists, followed by 24.3% who were agro-pastoralists, 7.1% involved in business, 2.2% students, and 1.8% had other occupations58. Access to communication resources was limited, with 94.3% of respondents lacking a radio, and 81.8% without a mobile phone. Moreover, 58.2% did not have a bank account, and 94.2% lacked internet access. Media exposure was also limited, with 87.1% having less frequent exposure59.

Migration patterns revealed that 1.5% of respondents migrated once, 17.6% migrated twice, 27.6% migrated three times, 34.4% migrated four times, and 18.9% migrated five times or more. Most migrations (85.9%) occurred within the Fentale District, while 14.1% migrated outside the district. Regarding migration dynamics, 45.7% of households reported that the head of the household was the primary migrant, 27.7% involved all family members, and 26.6% involved young men migrating mostly60.

Health-seeking behavior varied, with 23.6% of respondents seeking treatment at health facilities, 43.3% from traditional healers, 31.7% from religious places, and 1.4% from other sources61. Proximity to healthcare centers was a key factor: 42.5% lived less than one hour from a health center, while 57.5% lived more than an hour away62. Family planning discussions were minimal, with 93.2% of respondents never discussing family planning with their partners, and only 6.8% having done so63.

Regarding family size, 38.0% of respondents had families with four or fewer members, 51.4% had five to eight members, and 10.6% had nine or more members. Desired family size preferences were as follows: 16.7% preferred no more children, 16.1% desired one to two children, 39.2% wanted three to five children, and 28.0% wished for more than five children. Additionally, 83.3% of respondents expressed a desire for more children in the future, while 16.7% did not64 (See Table 1).

Utilization of different contraceptive methods among married couples

Table 2 presents the percentage of married couples within the reproductive age group who reported using any family planning (FP) methods, including modern methods, in Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia. The analysis focused on couples excluding those currently pregnant, highlighting the proportion of those using various FP methods at the time of the survey. The study assessed the prevalence of different FP methods and the factors influencing modern contraceptive utilization among married couples in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District.

The findings reveal that 27.4% of couples are currently using some form of FP, with 18.2% specifically using modern methods. Among short-term methods, injectables are the most widely used (7.5%), followed by pills (5.9%) and male condoms (0.9%). Long-term methods, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, are less common, with only 3.6% and 0.4% of couples using them, respectively. Natural methods, including lactational amenorrhea (3.5%), periodic abstinence (3.2%), and withdrawal (2.4%), also contribute to the contraceptive practices in this community.

The data highlights a preference for short-term contraceptive methods over long-term options among married couples in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District. Currently, 256 married couples are using modern contraceptive methods, representing 18.2% of the surveyed population. Short-term methods, particularly pills, male condoms, and injectables, are the most commonly used, while natural methods such as lactational amenorrhea are also notable. The adoption of modern contraceptive methods (18.2%) is higher than the use of traditional methods (9.1%), which include natural methods, though traditional methods are more common than long-term methods (3.9%).

In summary, 27.4% of married couples in Fentale District currently use some form of contraceptive method. The data presented in Table 2 provides valuable insights into the contraceptive practices within the pastoralist communities of Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia.

Reasons for not using contraception among married couples

The study identified several key reasons why married couples in the pastoralist community of Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia, refrained from using contraception, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The predominant reason was the desire for more children, cited by 68.7% of respondents, reflecting the cultural value placed on larger families within this community2. Religious opposition was the second most common reason, with 63.0% of respondents indicating that their religious beliefs discouraged contraceptive use, highlighting the strong influence of religion on family planning decisions70. Partner opposition was also significant, reported by 51.1% of couples, indicating that spousal dynamics play a crucial role in contraceptive decision-making70.

Moreover, 42.9% of respondents expressed concerns about potential side effects, suggesting either apprehensions or misunderstandings about the health risks associated with contraceptive methods71. A smaller proportion of respondents attributed their non-use to other health-related issues (12.5%), a lack of knowledge about contraceptive methods (12.2%), and uncertainty about where to obtain contraceptives (8.5%) highlighting gaps in access to information and services within the community.

Infrequent sexual activity was cited by 2.4% of respondents as a reason for not using contraception, though this was a less common factor71. These findings, as summarized in Fig. 2, illustrate the complex interplay of cultural, religious, informational, and personal barriers that impact contraceptive use within this pastoralist community.

Disparities in condom use and awareness: implications for sexual health education

Figure 3 highlights a significant disparity in condom use among couples in the study. It shows that only 15.1% (212) of respondents primarily used condoms for the prevention of STIs/HIV, while a mere 0.9% (12) recognized them as a method for family planning. This suggests that the focus on using condoms is largely for health protection rather than for contraceptive purposes or dual purposes72. The findings indicate that couples in the study predominantly use condoms to safeguard against STIs/HIV rather than to prevent pregnancy. This trend points to a broader issue within the community concerning awareness and education about contraceptive methods. The limited recognition of condoms as a family planning option suggests potential gaps in understanding their dual purpose, underscoring the need for integrated sexual health education that emphasizes both pregnancy prevention and STI protection73.

Additionally, this limited awareness of condoms as a contraceptive tool may reflect deep-seated cultural attitudes toward family planning within the community, where traditional views on childbearing remain influential. Addressing these cultural perspectives and enhancing education about the multifaceted benefits of condom use could be vital for improving reproductive health outcomes in the community74. Family size preferences may also overshadow discussions about contraceptive methods, further highlighting the need for targeted educational interventions75.

Relationship of socio-demographic, socio-economic, and reproductive history to modern contraceptive utilization

The study assessed the prevalence and predictors of modern contraceptive use among married couples in the pastoralist communities of Fentale District, Eastern Ethiopia, as detailed in Table 3. It found that 18.2% of couples used modern contraceptives, with a significant proportion (81.8%) not utilizing any methods (p < 0.05)2.

Key socio-demographic factors influencing contraceptive use included Age at First Marriage. Couples where the wife married at 15 years or younger had the highest proportion of non-users (57.8%). Use increased with age, with the lowest usage observed in the 15–19 age group (12.9%) and higher usage in those aged 20–24 (30.1%) and 25–29 years (28.1%) (p < 0.05)76.

Educational Status was also a significant determinant, with individuals with no formal education showing the highest rates of non-use (57.3%), followed by those with primary education (39.5%) and secondary or higher education (22.3%) (p < 0.05)1. Additionally, Religion had a notable impact, as a greater proportion of Muslims (94.5%) were non-users compared to Christians (5.5%) (p < 0.05)77.

Occupational Status further influenced contraceptive behavior. Nomadic-pastoralists had the highest non-user rate (44.9%), while agro-pastoralists (34.4%) and businesspeople (12.5%) demonstrated higher contraceptive use (p < 0.05)1.

The Access to Resources emerged as a critical factor in contraceptive use. Couples lacking access to radios, mobile phones, or bank accounts exhibited higher rates of non-use, while those with access to these resources were more likely to use contraceptives. Specifically, 90.6% of those with a bank account used contraceptives, compared to just 13.7% of internet users (p < 0.05)78.

Exposure to Media also had a positive influence, with 22.3% of couples frequently exposed to media adopting contraceptive methods (p < 0.05)79. Migration Patterns impacted contraceptive use, with couples who migrated twice showing the highest usage rates (40.6%). However, frequent migration was associated with lower usage, while those migrating within Fentale District had higher usage (93.8%) (p < 0.05)80.

Health-Seeking Behavior was another critical determinant. Couples seeking treatment in health facilities had significantly higher contraceptive use (80.9%) compared to those relying on traditional healers (48.9%). Proximity to health centers also played a role; couples living less than an hour away from a health center had a notably higher usage rate (72.3%) (p < 0.05)81.

Couple Discussions about family planning strongly correlated with increased contraceptive use (17.2%) (p < 0.05)1. Furthermore, Fertility Preferences influenced contraceptive use, with couples desiring fewer children (1–2) exhibiting higher usage rates (23%), whereas those wanting more than five children had lower usage rates. Couples with no desire for more children had the highest rates of contraceptive use (25.4%) (p < 0.05)37.

In conclusion, modern contraceptive use in Fentale District was significantly influenced by socio-demographic factors such as age, education, and religion, along with socio-economic factors like occupation, access to resources, and migration. Additionally, reproductive history and proximity to health services were key factors shaping contraceptive behavior. For further details, please refer to Table 3.

Key socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics influencing modern contraceptive utilization in the Fentale district

Table 4 highlights several socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics that significantly influence modern contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District:

Age at first marriage

Couples where the wife married at or before the age of 15 years exhibited lower odds of using modern contraceptives compared to those married at or after 18 years (AOR = 0.613, 95% CI: 0.315–1.193)67.

Age

Increasing age was associated with decreased odds of modern contraceptive utilization. Specifically, couples aged 40–44 years and those aged 45 years and older had significantly lower odds of contraceptive use compared to couples aged 15–19 years83.

Educational status

Couples with no formal education showed lower odds of contraceptive use compared to those with secondary education or higher (AOR = 2.878, 95% CI: 1.976–4.191)84.

Religion

Christians had higher odds of modern contraceptive use compared to Muslims, although this difference was not statistically significant (AOR = 2.501, 95% CI: 0.287–21.832)85.

Occupational status

Couples engaged in business had significantly higher odds of contraceptive use compared to nomadic-pastoralists (AOR = 7.461, 95% CI: 3.324–16.748)86.

Access to resources

Ownership of communication devices, such as mobile phones, was positively associated with contraceptive use. Couples with mobile phones had significantly higher odds of contraceptive use compared to those without (AOR = 3.628, 95% CI: 1.573–8.363)87.

Reproductive history factors affecting contraceptive use

Reproductive history factors, such as age at first birth and age at marriage, also play a crucial role in influencing contraceptive use among married couples:

Age at first birth

While specific data on age at first birth was not provided, it is generally understood that younger brides may face barriers to accessing and utilizing modern contraceptive methods effectively, which can lead to lower contraceptive uptake88 .

Desired number of children

Couples desiring more children exhibited significantly lower odds of contraceptive use compared to those with no desire for future children (AOR = 0.406, 95% CI: 0.185–0.890)37.

Implications for public health policies and interventions

The findings from this study have several implications for public health policies and interventions aimed at increasing contraceptive use in the Fentale District:

Targeted interventions

There is a need for targeted interventions that address socio-demographic determinants, such as age at first marriage, educational status, and occupational status, to promote contraceptive use and improve reproductive health outcomes76.

Education and awareness campaigns

Culturally sensitive education and awareness campaigns involving religious leaders can help address barriers to contraceptive use rooted in cultural and religious beliefs89.

Access to family planning services

Enhancing access to family planning services through mobile clinics or community health workers is vital for ensuring cultural appropriateness and accessibility90.

Engagement of both spouses

Promoting male engagement in family planning and advocating for dual protection methods can help improve contraceptive uptake and reproductive health outcomes10.

Community collaboration

Collaboration with community members and stakeholders is essential to effectively address reproductive health disparities and empower individuals to make informed decisions about their reproductive health91. By implementing these strategies, public health initiatives can significantly improve contraceptive uptake and reproductive health outcomes within the pastoralist communities of the Fentale District. For further details, please refer to Table 4.

Qualitative findings

Participants frequently expressed confusion about contraceptive methods, indicating a significant gap in understanding within the community. For instance, a 30-year-old woman in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) remarked, “We hear about contraceptives, but we don’t know how to use them properly.” This sentiment underscores the widespread misconceptions surrounding modern contraceptive methods, which may hinder effective utilization and acceptance in the community [92).

Misperceptions on Contraceptive Methods were common, particularly regarding specific methods like condoms. A male health worker, interviewed during a Key Informant Interview (KII), noted, “We don’t know much about condoms and how they can help with family planning.” This statement underscores the need for improved education on the dual role of condoms in both STI prevention and family planning93.

Religious beliefs significantly shaped attitudes toward contraceptive use within the community. A 28-year-old woman in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) remarked, “Our religion teaches us that having children is a blessing.” These beliefs often discourage the use of contraceptives, representing a deeply rooted barrier that influences family planning decisions70.

Religious and spousal opposition emerged as significant factors affecting contraceptive use, with 63% of respondents citing religious objections. A 35-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) explained, “My husband decides when we have children, and I can’t use contraceptives without his consent.” This statement underscores the dual influence of religious beliefs and spousal control in shaping contraceptive decision-making94.

Male dominance significantly influences reproductive decisions in pastoralist communities. A 30-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) noted, “Women in our community cannot travel to the city freely; it’s considered inappropriate unless it’s for specific duties.” This statement highlights the power imbalance that limits women’s autonomy in family planning95.

Traditional views on masculinity often hinder male participation in discussions about contraception. A 32-year-old man in a Key Informant Interview (KII) remarked, “As men, we feel responsible for family decisions.” This statement suggests that some men perceive discussions about family planning as potentially undermining their authority96.

Effective communication between couples was identified as crucial. A 33-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) explained, “I want to use contraceptives, but my husband thinks we should have more children.” This illustrates how communication gaps between partners can influence contraceptive decisions16.

Cultural norms in the community often favor larger families. A 25-year-old woman in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) shared, “In our culture, having more children means more help with the livestock and household.” These beliefs perpetuate early marriage, impacting contraceptive decisions and uptake97.

The reliance on children for economic support and old-age security significantly shapes family planning choices. A 40-year-old participant in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) mentioned, “Children are our security for old age, especially with high child mortality rates.” This cultural perception creates challenges for families in accepting the idea of limiting family size98.

Limited access to healthcare services emerged as a recurring theme in the discussions. A 45-year-old man in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) remarked, “We need more healthcare services in our area to learn about family planning.” This gap in access directly affects families’ ability to seek out and utilize modern contraceptives99.

A significant barrier to contraceptive use identified in the study was the lack of information regarding available methods. A 33-year-old woman in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) expressed, “We need more information about family planning, but we don’t have the means to find it.” This statement underscores the critical need for targeted outreach and education programs to enhance awareness and accessibility of family planning resources38.

Geographical distance to healthcare services emerged as a significant challenge in the study. A 30-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) remarked, “Accessing health services is a real challenge.” This geographical isolation presents a substantial barrier for families seeking necessary contraceptive methods, limiting their ability to utilize available resources effectively38.

Migration patterns within the district significantly affected access to healthcare services. A 27-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) emphasized the necessity for community outreach, stating, “If health workers came to our community, many women would feel more comfortable with modern methods.” This underscores the critical role of mobile health services in pastoralist regions, suggesting that increased accessibility could enhance the acceptance and use of modern contraceptive methods100.

Mobile phones have emerged as crucial tools for accessing health information, particularly in remote areas. A 29-year-old woman in an In-Depth Interview (IDI) noted, “Having a mobile phone helps us get information about health services and contraceptive options.” This finding indicates that technology can significantly enhance access to reproductive health information, thereby potentially improving contraceptive use and family planning outcomes in underserved communities101.

The qualitative insights gathered during this study offer a deeper understanding of the social, cultural, and logistical factors influencing family planning decisions and contraceptive use among pastoralist communities in the Fentale District102. These findings highlight the complexity of factors that affect reproductive health behaviors and underscore the need for targeted interventions that address the unique challenges faced by these communities.

Results and discussion

The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings in this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting modern contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District. Conducted in the Fentale District of Eastern Ethiopia, the study employed a mixed-methods approach to investigate the utilization of family planning (FP) methods among married couples. The prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District was determined to be 18.2%. Participants expressed confusion and misinformation regarding contraceptive methods, contributing to the low uptake. For instance, one woman noted, “We hear about contraceptives, but we don’t know how to use them properly.” This finding is supported by quantitative data, which revealed that misinformation is significantly associated with lower contraceptive use rates (AOR = 0.564)2. The results underscore the urgent need for culturally tailored family planning education to address these misconceptions and promote a better understanding of modern contraceptive methods. Targeted educational interventions are crucial to dispelling myths and providing accurate information; however, the study’s reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases due to social desirability103. Future research could employ mixed-methods approaches to explore the roots of these misconceptions more deeply103. Furthermore, misinformation is also prevalent regarding specific contraceptive methods, such as condoms. Only 15.1% of respondents reported using condoms for STI prevention, while just 0.9% recognized them as a viable family planning tool93. A health worker highlighted this issue, stating, “We don’t know much about condoms and how they can help with family planning.” This limited understanding suggests a need for educational initiatives that cover both STI prevention and contraception. Addressing this gap is crucial, though the study may not capture all reasons for the limited awareness of condoms as a family planning option104. Future studies could further investigate the barriers to condom use and assess the effectiveness of interventions aimed at raising awareness and acceptance105.

Religious beliefs also significantly influence attitudes toward contraceptive use in the community. Many participants reported that their religious teachings discourage the use of contraceptives. As one participant expressed, “Our religion teaches us that having children is a blessing.” This perspective is reflected in quantitative analysis, which shows that adherence to religious teachings is a significant factor in contraceptive use, with non-Muslim participants exhibiting higher odds of using contraceptives (AOR = 2.501)70. Addressing religious beliefs in family planning efforts is crucial for enhancing contraceptive uptake, though the diversity of religious perspectives in the community may not be fully represented in this study24. Future research could explore ways to engage religious leaders in supporting family planning and better understand the impact of various religious teachings on contraceptive behavior70.

This section effectively combines qualitative insights and quantitative data to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing modern contraceptive use in the Fentale District, highlighting the need for culturally sensitive and inclusive approaches to family planning education. Notably, religious opposition to contraception was reported by 63% of respondents, reinforcing the community’s preference for larger families94. Additionally, spousal dynamics played a significant role in family planning decisions, with 51.1% of couples citing partner opposition as a key barrier. One 35-year-old woman explained, “My husband decides when we have children, and I can’t use contraceptives without his consent.” This quote highlights the complex interplay between religious beliefs and spousal approval in influencing contraceptive use decisions106. The results suggest that successful interventions should address both religious and gender-related barriers to improve contraceptive acceptance. However, the study may not fully capture the intricate dynamics of spousal relationships and their interactions with religious beliefs. Future research could explore ways to enhance spousal communication and joint decision-making in family planning contexts, promoting more equitable outcomes107.

Moreover, male dominance in decision-making emerged as a persistent theme in the study. Many women expressed concerns about their limited autonomy in making reproductive decisions. For example, a 30-year-old woman described, “Women in our community cannot travel to the city freely; it’s considered inappropriate unless it’s for specific duties like livestock farming or house building. Meanwhile, men go to the city, gather information, and if they deem it important, share it with us. We rely on our husbands for many things, including family planning information.” A community leader further reinforced this by stating, “In our society, the husband’s word is final when it comes to family planning. Even if a woman wants to space her children, she cannot proceed without her husband’s approval. Men fear that controlling births may reduce their standing in the community, where larger families are highly respected.” These insights reflect how male dominance restricts women’s ability to make informed decisions about their reproductive health. Quantitative data supports these findings, showing that areas with greater male involvement had higher contraceptive use rates (AOR = 0.418)108. This suggests that engaging men in family planning discussions can improve outcomes. The study underscores the importance of designing interventions that promote gender equality and empower women in reproductive decisions, although further research is needed to understand the underlying reasons for male dominance and how to encourage shared decision-making in these contexts.

Traditional views on masculinity often discouraged men from participating in family planning discussions, as many felt that engaging in such conversations indicated weakness. One male participant stated, “As men, we feel responsible for family decisions.” This perspective often limits male engagement in discussions about contraceptives, despite evidence that higher male involvement can lead to better family planning outcomes (AOR = 0.418)109. These findings suggest that promoting shared responsibility in family planning discussions can lead to increased contraceptive use. However, the study may not fully explore the barriers to male involvement and the factors that encourage it. Future studies could focus on identifying effective strategies for engaging men in family planning, exploring how traditional gender roles can be reshaped to support better reproductive health outcomes110.

Effective communication between couples plays a critical role in family planning decisions. Many women reported that their husbands were the primary decision-makers regarding contraception. One participant shared, “I want to use contraceptives, but my husband thinks we should have more children.” This sentiment aligns with the study’s findings, which showed that discussions on family planning significantly increase contraceptive uptake, with an adjusted odds ratio (AOR = 15.708) for couples who engage in such conversations compared to those who do not111. This underscores the importance of fostering open communication between partners. Research suggests that couples who engage in dialogue about family planning are more likely to adopt modern contraceptive methods; as such discussions help to align their reproductive goals and promote mutual support16, . However, the study may not fully capture the nuances of couple communication and cultural factors that may influence these interactions. Future research could explore the most effective strategies for enhancing communication between couples and how these strategies impact contraceptive use in different cultural contexts112.

Overall, these findings emphasize the need for culturally sensitive and gender-inclusive approaches to family planning in the Fentale District. Interventions that encourage male participation, promote open communication, and address religious and cultural beliefs are critical to improving contraceptive use and reproductive health outcomes in this context. Further research is needed to develop targeted strategies that respect cultural norms while promoting equitable decision-making in family planning2.

Cultural norms surrounding large families emerged as a significant barrier to contraceptive use in the Fentale District, where the pastoralist community perceives having more children as advantageous for both economic and social reasons. One participant explained, “In our culture, having more children means more help with the livestock and household.” This cultural preference is reflected in the study’s quantitative findings, which indicated that women married before the age of 18 had lower odds of using modern contraceptives (AOR = 0.613)20. The high rates of early marriage, with 46.3% of women married young, further contribute to challenges in accessing and effectively utilizing contraceptives2. Additionally, 51.4% of respondents reported having larger families of 5 to 8 members, underscoring the economic and social value placed on larger family sizes113,114. These findings highlight the urgent need for interventions that address cultural norms and early marriage by engaging community leaders to shift perspectives on the benefits of family planning115. While the study provides valuable insights, it may not fully explore the underlying socio-cultural reasons behind these preferences, which indicates a need for future research to develop targeted strategies that resonate with community values.

The importance of children for economic security in old age and labor in livestock farming further drives the preference for larger families. One participant from a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) stated, “Children are our security for old age, especially with high child mortality rates.” Quantitative data supports this view, with 28% of the population desiring more than five children116. This reliance on children for economic support, particularly in pastoralist livelihoods, influences reproductive decisions, making it challenging to adopt modern contraceptive methods117. Addressing these cultural and economic influences is vital for the success of family planning programs. Tailored strategies that consider the economic roles of children and provide alternatives could enhance the acceptance of modern contraceptives118. Future studies could further investigate how economic needs interact with cultural beliefs to inform interventions that align with community values.

Access to healthcare services and education also remains a critical challenge. A significant proportion of participants (93.2%) reported that they had never discussed family planning with health workers, and many faced difficulties accessing reliable healthcare, particularly in remote areas. High child mortality rates drive families to have more children as a form of insurance against loss. As one community member remarked, “We need more healthcare services in our area to learn about family planning.” This gap in access severely limits the uptake of modern contraceptive methods38. Quantitative data further revealed that over half of the population lives more than an hour from the nearest health center, creating significant barriers to accessing family planning services119. While the study highlights the challenges of healthcare access, it may not fully capture the diverse barriers faced by different socio-economic groups. Future research could explore the specific healthcare needs of various demographics, helping to design tailored interventions that improve access to family planning services120.

In addition, the study revealed that limited access to information about family planning contributes to low contraceptive uptake. Many respondents cited the absence of discussions surrounding family planning at home or within their communities. One participant noted, “There’s a lack of information about family planning options; we often rely on word of mouth.” This reliance on informal sources limits access to accurate and comprehensive information about available contraceptive methods121. The study’s quantitative data revealed that only 22.5% of households reported having televisions, restricting access to vital family planning information. Improving healthcare access and promoting health education are crucial for enhancing contraceptive uptake and addressing underlying issues related to child mortality and family planning discussions122. However, the study’s reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases, necessitating further investigation into access barriers and effective communication strategies.

In conclusion, this study highlights the complex interplay of socio-economic factors, cultural beliefs, and spousal dynamics affecting modern contraceptive use among married couples in the Fentale District. The findings emphasize the need for culturally sensitive interventions that address misinformation, promote gender equality, and enhance access to family planning services. Engaging men in family planning discussions and empowering women to make informed choices about their reproductive health are crucial for improving contraceptive uptake and achieving better reproductive health outcomes in this community. Future research should focus on exploring the effectiveness of targeted interventions and the long-term impact of culturally sensitive approaches on family planning practices in pastoralist community.

Recommendations

Recommendations for future studies