Abstract

Research on the impact of different leadership styles on safety behavior has been extensively conducted across various fields. However, few studies have investigated the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety behavior, particularly between inclusive leadership and safety behavior (safety participation and safety compliance) among the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. This study, based on social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, and organizational personification theory, explains the relationship between inclusive leadership and the safety behavior of high-altitude railway construction workers (safety participation and safety compliance) by using safety self-efficacy as a mediating variable and perceived organizational support as a moderating variable. To address common method bias, a multi-source and multi-stage data collection design was used, gathering 315 valid questionnaires from construction workers on 10 high-altitude railway construction projects, with hypothesis testing performed through regression analysis. The results indicate that inclusive leadership not only directly affects safety behavior (safety participation and safety compliance) but also that safety self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety behavior (safety participation and safety compliance). Additionally, perceived organizational support not only enhances the positive impact of inclusive leadership on safety self-efficacy but also strengthens the positive effect of inclusive leadership on safety behavior (safety participation and safety compliance). These findings enrich the research on the correlation between leadership styles and safety behavior among the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers, and provide new perspectives and approaches for preventing safety accidents in high-altitude railway construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The “14th Five-Year Plan” explicitly proposes accelerating the construction of a strong transportation nation and promoting high-quality development of infrastructure such as railways1. High-altitude railway construction, as a crucial component of China’s transportation infrastructure development, plays a significant role in promoting regional coordinated development, driving regional economic growth, and strengthening national unity. However, the unique natural environment and complex construction conditions in high-altitude areas pose tremendous challenges to railway construction, with frequent safety accidents being a key constraint on high-altitude railway development2,3. Research indicates that over 70% of workplace accidents are related to unsafe employee behavior4.

Safety behavior refers to the series of actions and decisions individuals take at work to avoid accidents and injuries5. For high-altitude railway construction workers, who are directly involved in railway construction, their safety behavior directly impacts the safety level and quality of high-altitude railway projects. Research has shown that among the many factors influencing employees’ safety behavior, leadership style plays a crucial role6,7,8. As leaders of organizations, their different leadership styles (such as transformational leadership9, transactional leadership10, and laissez-faire leadership11) and their behavior patterns, decision-making models, and management strategies can directly or indirectly influence employees’ safety behavior. With the continuous development of leadership theories, inclusive leadership, as an emerging leadership style, emphasizes respecting and including employees’ differences, focusing on their needs, and making them feel respected and valued. This is beneficial for enhancing employees’ positive emotions at work and changing their attitudes and behaviors12. Therefore, research on the correlation between inclusive leadership and employee behaviors (such as voice behavior13, organizational citizenship behavior14, and innovative behavior15) has received significant attention in many fields. However, there is relatively less research on the relationship between inclusive leadership and employees’ safety behavior. Particularly, with the rise of the new generation of workers, who are becoming the main force in high-altitude railway construction, they exhibit significant differences in values, work attitudes, work methods, and adaptability compared to traditional construction workers16,17. Specifically: First, new-generation workers generally have higher educational levels and may not adapt well to traditional safety education and training methods, preferring interactive and innovative learning approaches. Second, they place greater emphasis on personal development and may be more interested in high-risk, high-reward job opportunities, leading to risk-taking behaviors at work. Third, they may have poorer adaptability to harsh working environments and conditions, making them more susceptible to fatigue, anxiety, and depression, which can result in unsafe behaviors. Therefore, effectively guiding and managing the new generation of workers to improve their safety behavior is a scientific problem that needs to be addressed in high-altitude railway construction safety management. This study aims to explore the impact and internal mechanisms of inclusive leadership on the safety behavior of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers, offering guidance and practical value for improving their safety behavior levels. Additionally, it provides new insights and perspectives for preventing safety accidents in high-altitude railway construction.

From a relational perspective, the development of inclusive leadership styles originates from social exchange theory18 and is closely related to social cognitive theory19 and organizational personification theory20. This study investigates the relationship between inclusive leadership and the safety behavior of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers within the context of high-altitude railway construction safety, using these three theories as a framework. Firstly, social exchange theory posits that all human activities are governed by exchange activities that can bring rewards and benefits18,21. In other words, it suggests that when employees perceive care and support from their leaders, they are motivated to reciprocate. Inclusive leadership, which respects employees’ opinions and addresses their needs, makes the new generation of construction workers feel valued and respected. This, in turn, encourages them to adhere more willingly to safety regulations as a way to reciprocate the trust placed in them by their leaders. Thus, this study posits that inclusive leadership has a significant impact on the safety behavior of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. Secondly, self-efficacy, as a core variable in social cognitive theory, refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to complete tasks. Individuals with high self-efficacy maintain a positive attitude towards challenges in complex environments and are motivated to use effective methods to control their behavior. Individual behavior is influenced by different leadership styles. Empirical research in various fields indicates that self-efficacy not only directly affects behavior but can also mediate the influence of different leadership styles on behavior22,23,24. However, Seers25 suggests that self-efficacy in specific domains, scenarios, or issues has a more pronounced effect on predicting specific behaviors compared to general self-efficacy. Therefore, in the context of high-altitude railway construction safety, this study posits that safety self-efficacy may mediate the relationship between inclusive leadership and the safety behavior of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. Finally, organizational personification theory views organizations as entities with human-like traits and emotions. In the high-altitude railway construction environment, inclusive leadership can approach the new generation of construction workers with openness, respect, and understanding, encouraging their active participation in decision-making and providing development opportunities. This enhances workers’ sense of belonging and self-efficacy. Perceived organizational support is the subjective feeling of whether the organization cares about employees’ welfare, values their contributions, and is willing to provide necessary resources. When new generation workers feel strong organizational support, the positive impact of inclusive leadership on their safety behavior and safety self-efficacy is further strengthened. Therefore, this study proposes that perceived organizational support may play a moderating role in the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety self-efficacy and safety behavior.

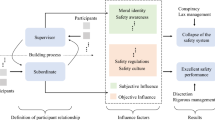

In summary, this study enriches the research on inclusive leadership styles within the context of construction safety and expands on the mechanisms by which inclusive leadership affects the safety behavior of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. It explores: (1) whether inclusive leadership influences the safety behavior of these workers; (2) whether safety self-efficacy mediates the effect of inclusive leadership on their safety behavior; and (3) whether perceived organizational support moderates the impact of inclusive leadership on both safety behavior and safety self-efficacy. The specific model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Theory and hypotheses

Inclusive leadership and safety behavior

Safety behavior is defined as a series of actions that comply with safety norms and standards to avoid accidents and injuries, ensuring both personal and others’ safety26. Since safety behavior is a special form of job performance27, its dimensions need to be traced back to the research on job performance dimensions. Locke28 classified job performance dimensions into task performance and contextual performance. Neal and Griffin27, based on related research, introduced task performance and contextual performance into the field of construction safety, dividing safety performance into safety compliance and safety participation at the behavioral level. Safety compliance refers to role-in behaviors where workers strictly follow established safety rules, procedures, and standards without engaging in prohibited activities. For example, accurately wearing personal protective equipment and following prescribed procedures for working at heights. Safety participation refers to role-out behaviors where workers actively engage in safety management, including offering suggestions for safety management, participating in various safety training and educational activities, and reminding peers to follow safety practices, thus promoting good safety habits within the team. For example, kindly reminding and correcting colleagues’ unsafe behaviors.

The social exchange theory posits that relationships between people are fundamentally based on exchange, where individuals assess interactions based on the balance of contributions and rewards, and decide their behavior based on this evaluation18,21. In the workplace, the relationship between employees and leaders can also be explained by social exchange theory. When employees receive valuable resources from leaders, such as support, respect, and trust, they are likely to reciprocate with positive work attitudes and behaviors. With the rise of the new generation workforce, young construction workers often desire respect and recognition in their work and seek the realization of personal value29,30. Particularly in the challenging and complex high-altitude railway construction environment, where there are numerous safety risks and construction workers face both physical and psychological pressures, these workers have higher expectations for support and resource assurance from their leaders. In other words, they need leaders who understand their situation and provide necessary care and assistance to stimulate their enthusiasm and initiative31. Inclusive leadership, which focuses on listening to employees’ diverse voices, respecting individual differences, and creating fair opportunities and environments, can offer new generation high-altitude railway construction workers the respect and trust they need. This respect is an important psychological resource that meets their needs for self-realization and recognition12,32. Moreover, when new generation construction workers receive support and recognition from inclusive leadership, they perceive it as a form of “benefit” and reciprocate by feeling a sense of responsibility and obligation. They may adhere more strictly to safety regulations, proactively implement safety measures, actively participate in safety training, and demonstrate a more positive work attitude and safety behavior in response to the leader’s trust and support. Therefore, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a

Inclusive leadership is positively correlated with safety compliance among new generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

Hypothesis 1b

Inclusive leadership is positively correlated with safety participation among new generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

The mediating role of safety self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, proposed by the renowned American psychologist Bandura33, refers to “an individual’s judgment and estimation of their own capability to perform a particular behavior.” It reflects a person’s belief and confidence in their ability to complete specific tasks or achieve goals. This concept not only determines an individual’s attitude and behavior choices when facing challenges but also profoundly influences their level of effort and persistence. When individuals experience repeated successes in their past endeavors, their sense of self-efficacy gradually increases, leading to greater courage and motivation to tackle new and more challenging tasks. Conversely, frequent failures can weaken self-efficacy, resulting in hesitation, withdrawal, or even abandonment of similar tasks34.

As research progresses and application scenarios expand, the scope of self-efficacy has been refined to specific areas. For instance, safety self-efficacy focuses on an individual’s belief and confidence in effectively taking actions to ensure their own and others’ safety in safety-related situations and tasks35. However, in high-altitude railway construction—a field characterized by extreme challenges and risks—unique geographical and climatic conditions such as low pressure and oxygen levels, cold dryness, variable climate, and strong ultraviolet radiation create numerous difficulties and safety hazards17. Thus, construction workers not only need solid professional skills and rich experience but also a strong belief in their ability to handle various potential safety issues. This confidence, especially among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers, will directly impact their work performance and construction safety when facing complex and demanding environments.

In high-altitude railway construction, an inclusive leadership approach creates a positive work environment for the new generation of construction workers. Specifically, this is demonstrated by: (1) Inclusive leadership fully listening to and respecting the ideas and suggestions of the new generation of workers, making them feel valued and recognized, thereby enhancing their confidence in their work, including confidence in their ability to ensure their own safety, which improves their safety self-efficacy; (2) Inclusive leadership providing more practical opportunities and guidance to help these workers gain successful experience in their actual work, with each successful handling of safety risks reinforcing their perception of their own safety capabilities, thereby improving their safety self-efficacy; (3) In an inclusive team, the new generation of workers can observe how colleagues effectively handle safety issues with the support of leadership. This role modeling and indirect experience also help them improve their assessment of their own safety abilities and enhance their safety self-efficacy. Therefore, this study proposes the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2

Inclusive leadership is positively correlated with safety self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, as an internal motivational factor that individuals can control, has been extensively validated by empirical research for its significant role in both behavioral intentions and actual behaviors36,37. A meta-analysis by Wang38 indicated that the correlations between self-efficacy and behavioral intentions and actual behaviors are r = 0.63 and r = 0.46, respectively. In research on safety behaviors, safety self-efficacy has been considered one of the key predictors of safety behavior39, with many empirical studies highlighting its role in promoting safety behavior39,40,41. The new generation of construction workers, as a fresh force in high-altitude railway construction, plays a crucial role in construction safety. New-generation workers with high safety self-efficacy often approach safety issues with a more positive mindset. They believe in their ability to handle the complex and changing construction environment and potential safety risks. This positive belief drives them to thoroughly prepare for safety before construction, such as carefully checking personal protective equipment, familiarizing themselves with construction processes, and safety regulations. Furthermore, during actual construction, workers with high self-efficacy are more likely to voluntarily adhere to safety regulations. They are confident in their ability to perform safety operations and can strictly follow standard procedures, reducing safety accidents caused by violations. Even when facing sudden safety situations, they can quickly and effectively respond, taking appropriate emergency measures to minimize danger and loss41. At the same time, safety self-efficacy also affects communication and collaboration among construction workers. New-generation workers with high self-efficacy are more willing to share safety experiences and knowledge with colleagues, actively participate in team safety discussions, and solve safety problems together. This positive interaction helps create a mutually supervised and supportive safety work environment, enhancing the overall safety level of the construction team40,41. In contrast, new-generation workers with lower self-efficacy may have a negative attitude towards safety work. They might doubt their ability to handle safety risks, leading to careless and negligent behaviors that result in unsafe practices. Therefore, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a

Safety self-efficacy is positively associated with safety compliance.Hypothesis 3b: Safety self-efficacy is positively associated with safety participation.

Hypothesis 3b

Safety self-efficacy is positively associated with safety participation.

Summarizing, social cognitive theory emphasizes the close relationship between individuals’ beliefs and their environment. In the context of high-altitude railway construction, an inclusive leadership style is a key environmental factor. As mentioned earlier, inclusive leadership respects and listens to the opinions and needs of construction workers, encourages their participation in decision-making, and provides support and resources, thereby creating a positive, open, and trusting work environment12. When construction workers perceive this inclusiveness from their leaders, they feel a greater sense of belonging and involvement, believing their voices are valued. This enhances their self-worth and confidence, leading to a more positive perception of their ability to ensure construction safety, i.e., increasing their safety self-efficacy. Additionally, construction workers with higher safety self-efficacy translate their beliefs into work practices, effectively controlling their behavior and managing potential negative outcomes when facing complex and challenging tasks, thus improving their safety behavior level. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a

Safety self-efficacy mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety compliance among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

Hypothesis 4b

Safety self-efficacy mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety participation among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

The moderating role of perceived organizational support

Perceived organizational support is the extent to which individuals perceive the organization as supporting their work-related resources. These resources include concern for employee interests, assistance provided to employees, and recognition of employee work value, among others42. From the perspective of organizational personification, perceived organizational support is akin to a warm and powerful embrace that gives construction workers a sense of security and belonging20,43. This perspective encourages employees to form emotional and cognitive connections in their interactions with the organization. Particularly in the challenging and risky environment of high-altitude railway construction, the new generation of employees needs to feel the organization’s care and support to enhance their sense of belonging and identity with the organization, which in turn influences their safety behavior.

Firstly, inclusive leaders create a work atmosphere that encourages diversity and embraces differences by demonstrating respect, fairness, and openness in their management style12. This leadership style can enhance employees’ self-efficacy15,44, making them more confident in taking safety measures when facing the unique challenges of high-altitude construction. Additionally, inclusive leadership can promote the free flow of information and effective communication among team members45,46, ensuring the transparency and adherence to safety protocols, thereby reducing accident risks. Secondly, perceived organizational support, as the degree to which employees perceive the organization as caring for their personal well-being, is a key factor influencing employee attitudes and behaviors47,48,49. In the harsh conditions of high-altitude construction, employees face both physiological and psychological pressures. At this time, the organization can effectively enhance perceived organizational support by providing safety training, health protection, and psychological counseling, which not only directly improves employees’ safety self-efficacy but also increases their loyalty and commitment to the organization, thereby enhancing their safety behavior. Therefore, perceived organizational support plays a catalytic role in this process. Specifically, based on an inclusive leadership style, higher perceived organizational support will further strengthen construction workers’ trust and dependence on leaders and the organization, thus improving their safety self-efficacy and safety behavior levels. Conversely, if construction workers do not feel supported by the organization or if the organization provides inadequate support and resources, even with the encouragement of inclusive leadership, they may still adopt cautious or negative attitudes towards their safety behavior. For example, insufficient investment in safety by the organization or delayed responses to reasonable demands from construction workers may lead them to perceive a lack of care from the organization. This can result in a reduction in their safety self-efficacy and might lead to non-compliant behavior during construction, reducing their enthusiasm and safety behavior levels, which in turn increases the occurrence of unsafe behaviors. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5

Perceived organizational support positively moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 6a

Perceived organizational support positively moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety compliance among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

Hypothesis 6b

Perceived organizational support positively moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety participation among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

Methods

Sample and procedure

In this study, we followed the standard procedures proposed in previous research on construction workers’ safety behaviors50,51. To avoid the impact of common method bias, we employed a phased data collection approach. Before data collection, we informed each participant about the purpose of our study and obtained their written consent to ensure the confidentiality of the data. Additionally, during the questionnaire completion process, each participant was assigned a unique code to match the questionnaires from each phase. After matching the questionnaires from each phase, the codes were removed from the survey.

This study collected data through questionnaires using mature scales for inclusive leadership, safety self-efficacy, perceived organizational support, and safety behaviors, targeting high-altitude railway construction workers. Data was gathered from frontline workers in ten project departments in high-altitude railway construction areas in Gansu, Qinghai, and Tibet. To ensure accuracy and a high response rate, data was collected through offline questionnaires in two phases. In the first phase, researchers collected data on inclusive leadership, and safety self-efficacy, distributing 396 questionnaires and receiving 362 back. After removing invalid responses, 346 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a response rate of 87%. Two months later (to avoid response biases), the second phase of the survey was conducted, focusing on perceived organizational support and safety behaviors. A total of 346 questionnaires were distributed, and 336 were returned. After removing invalid responses, 315 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a response rate of 91%, meeting the sample size requirements for the study52.

Ethical Approval: All research procedures involving human participants in this study were approved by the institution (Lanzhou Jiaotong University); and all methods comply with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or similar ethical standards.

Measures

Questionnaire items were marked using a seven-point Likert scale measuring from 1 = absolutely disagree to 7 = absolutely agree. The scales were translated from English to Chinese through translation and back translation procedures. Measurement of Proactive personality and other variables are described below:

Inclusive Leadership: The inclusive leadership scale used in this study is a revised version based on the scale developed by Wang Hui53 and Fang Yangchun54. It consists of 9 items, with representative items such as “When I encounter problems at work, my leader provides specialized advice.” The Cronbach’s α for inclusive leadership in this study is 0.962. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.879 to 0.963.

Safety Self-Efficacy: The safety self-efficacy scale is adapted from the General Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Chen et al.55, with items modified to reflect safety self-efficacy. It includes 6 items, such as “I am confident in my ability to effectively handle various safety-related tasks” The Cronbach’s α for safety self-efficacy in this study is 0.939. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.795 to 0.842.

Perceived Organizational Support: The perceived organizational support scale used in this study is a revised version of the scale developed by Eisenberger56, consisting of 10 items. A representative item is “Help is available from the organization when I have a problem” The Cronbach’s α for perceived organizational support in this study is 0.911. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.685 to 0.766.

Safety Behavior: Safety behavior is assessed using a 7-item scale developed by27, widely applied in studies of construction workers’ safety behavior. It includes two dimensions: safety compliance and safety participation. Safety participation has 3 items, such as “I put extra effort into improving workplace safety” with a Cronbach’s α of 0.895. Safety compliance has 4 items, such as “I use the correct safety procedures to complete my work” with a Cronbach’s α of 0.824. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.773 to 0.862.

Results

Statistical analysis of data

IBM SPSS Statistics 24, Amos Graphics 24 and PROCES v3.357 were used for statistical analysis of the data collected from this survey. First step: confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the issue of discriminant validity and possible common method bias among the key variables involved in this study. Second step: descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were conducted for each study variable, while convergent validity and composite reliability were tested. Third step: the theoretical hypotheses were tested using hierarchical regression.

Confirmatory factor analysis and homologous deviation analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the fit of the measurement’s models and to select the model with the best fit by comparing the models. Table 1 shows the fit indices of all tested models. Comparison of the results revealed that the five factor model fit was better (χ2 = 1180.222, df = 464, χ2/df = 2.544 < 3, RMSEA = 0.070 < 0.08, CFI = 0.919 > 0.9, TLI = 0.913 > 0.9) and the fit was significantly better than the other models, indicating that the measurement scale used in this study had excellent discriminant validity58.

As survey data were collected through self-evaluation, with each questionnaire involving key variables provided by the same subject, there may be a possibility of common method bias. To minimize this bias, this study employed anonymous measurement, phased and multi-source questionnaire methods. Additionally, SPSS 22.0 software was used to conduct Harman’s single factor test and factor analysis on all variables to analyze the collected data. The results indicated that there were five factors with eigenvalues greater than one (more than one), and the largest factor variance explained rate was 38.9% (less than 40%). Therefore, there was no significant common method bias59,60.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability. First, the AVE values for each construct are greater than 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) values are above 0.861, indicating that the structural model of this study has good convergent validity. Second, in the correlation analysis, proactive personality is positively correlated with safety self-efficacy (r = 0.396, p < 0.01), team member communication (r = 0.337, p < 0.01), safety compliance (r = 0.367, p < 0.01), safety participation (r = 0.334, p < 0.01), and safety transformational leadership (r = 0.143, p < 0.05). Safety self-efficacy is positively correlated with safety compliance (r = 0.368, p < 0.01) and safety participation (r = 0.299, p < 0.01). Similarly, team member communication is positively correlated with safety compliance (r = 0.317, p < 0.01) and safety participation (r = 0.341, p < 0.01).

Hypotheses testing

Firstly, Model 4 (a simple mediation model) from the PROCESS macro in SPSS, developed by Hayes57, was used to examine the mediating role of safety self-efficacy in the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety behavior. The results (Tables 3 and 4) show that inclusive leadership has a significant positive effect on safety participation (B = 0.293, t = 9.490, p < 0.001) and safety compliance (B = 0.273, t = 8.953, p < 0.001). When the mediator variable is included, the direct effects of inclusive leadership on safety compliance (B = 0.183, t = 5.746, p < 0.001) and safety participation (B = 0.173, t = 5.643, p < 0.001) remain significant, supporting hypotheses H1a and H1b. Inclusive leadership has a significant positive effect on safety self-efficacy (B = 0.334, t = 8.609, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H2. Safety self-efficacy has a significant positive effect on safety participation (B = 0.359, t = 8.911, p < 0.001) and safety compliance (B = 0.268, t = 6.411, p < 0.001), supporting hypotheses H3a and H3b. Additionally, the direct effects of inclusive leadership on safety compliance and safety participation, as well as the mediating effect of safety self-efficacy, do not include zero in the bootstrap 95% confidence interval (see Table 4), indicating that inclusive leadership can predict safety behavior not only directly but also through the mediating role of safety self-efficacy, thus supporting hypotheses H4a and H4b.

Second, using Model 8 from Hayes’s57 PROCESS macro in SPSS (Model 8 is a moderation model where the independent variable affects both the mediator and the dependent variable, which aligns with the theoretical model of this study), the moderating effect of perceived organizational support between inclusive leadership and safety self-efficacy, as well as safety behavior (safety compliance and safety participation), was examined. The results (Table 3) indicate that after including perceived organizational support in the model, the interaction term between inclusive leadership and perceived organizational support significantly predicted safety self-efficacy (B = 0.160, t = 2.868, p < 0.01), safety compliance (B = 0.112, t = 2.643, p < 0.01), and safety participation (B = 0.130, t = 3.618, p < 0.01). This suggests that perceived organizational support moderates the direct effects of inclusive leadership on safety self-efficacy, safety compliance, and safety participation. Therefore, hypotheses H5, H6a, and H6b are supported.

Further, a simple slope analysis was conducted (Figs. 2 and 3, and 4). From Fig. 2 and Table 5, it is evident that for participants with a high level of perceived organizational support (M + 1SD), inclusive leadership has a significant positive predictive effect on safety self-efficacy (simple slope = 0.433, t = 4.363, p < 0.001). For participants with a low level of perceived organizational support (M-1SD), inclusive leadership also significantly predicts safety self-efficacy (simple slope = 0.273, t = 3.401, p < 0.001), but to a lesser extent. This indicates that as perceived organizational support increases, the predictive effect of inclusive leadership on safety self-efficacy gradually rises (Fig. 3). Table 5 shows that for participants with high perceived organizational support (M + 1SD), inclusive leadership significantly predicts safety compliance behavior (simple slope = 0.276, t = 3.625, p < 0.001). For those with low perceived organizational support (M-1SD), inclusive leadership also significantly predicts safety compliance behavior (simple slope = 0.164, t = 2.305, p < 0.001), but the effect is smaller. This suggests that the predictive effect of inclusive leadership on safety compliance behavior increases with higher perceived organizational support. According to Fig. 4, for participants with high perceived organizational support (M + 1SD), inclusive leadership significantly predicts safety participation behavior (simple slope = 0.293, t = 3.692, p < 0.001). For those with low perceived organizational support (M-1SD), inclusive leadership also significantly predicts safety participation behavior (simple slope = 0.163, t = 1.896, p < 0.001), though the effect is smaller. This shows that the predictive effect of inclusive leadership on safety participation behavior increases with higher perceived organizational support. Additionally, we found that perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety self-efficacy more strongly than it moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety behaviors (safety compliance and safety participation).

Discussion

This study, based on social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, and organizational personification theory, proposes and tests the internal mechanisms through which inclusive leadership affects the safety behavior of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers in the context of high-altitude railway construction safety. Specifically, it examines the mediating role of safety self-efficacy and the moderating role of perceived organizational support. The study not only clarifies how inclusive leadership influences construction workers’ safety behavior (through the mediating role of safety self-efficacy) but also addresses the conditions under which inclusive leadership has a more significant impact on safety behavior (through the moderating role of perceived organizational support). The results of this study enrich the research on inclusive leadership and safety behavior, provide practical guidance for enhancing safety behavior levels among high-altitude railway construction workers, and offer new insights and perspectives for preventing safety accidents in high-altitude railway construction.

Theoretical implications

The three major theoretical contributions of this study to the literature are as follows:

-

1)

Inclusive leadership provides new empirical evidence for the application of social exchange theory in the workplace. Traditional social exchange theory focuses more on general organizational contexts, but research in extreme and specialized environments, such as high-altitude railway construction, is relatively scarce. With the rise of the new generation of workers, these individuals are gradually becoming the main force in high-altitude railway construction. They possess unique values and work preferences, placing greater emphasis on work-life balance and pursuing personalized work experiences. The emergence of inclusive leadership has broken the traditional single-leadership model and created a more equitable, open, and supportive work environment for construction workers. Compared to other leadership styles (such as transformational leadership, transactional leadership, charismatic leadership, etc.), inclusive leadership makes workers feel that their value is recognized and their needs are addressed, leading them to be more willing to engage in their work and exhibit positive safety behaviors in return. This study reveals the positive shaping effect of inclusive leadership on the safety behaviors of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. It not only supplements the impact of existing leadership styles on safety behavior but also enriches the application of social exchange theory in specific industries and populations, expanding its scope. Firstly, from the perspective of the costs and benefits of social exchange, inclusive leadership reduces the psychological costs for the new generation of construction workers. In high-altitude construction environments, workers endure significant physical and psychological stress. If they face harsh criticism, lack of understanding, or unfair treatment from leaders, their psychological burden increases further. However, inclusive leadership understands and accommodates employees’ mistakes, encourages them to propose new ideas and suggestions, which allows employees to feel psychologically safe and relaxed, reducing psychological costs associated with fear and anxiety. When individuals experience less psychological burden, they are more likely to reciprocate with positive behaviors. Therefore, new generation workers are more inclined to exhibit positive safety behaviors such as strictly adhering to safety regulations and proactively taking safety measures to maintain a good working environment and leadership relationship. Additionally, inclusive leadership helps establish long-term stable social exchange relationships. In high-altitude railway construction projects, which typically involve long durations and complex tasks, inclusive leadership is not a temporary strategy but a continuous leadership philosophy and behavior model. Through long-term inclusiveness and support, a deep trust and dependency relationship is established between the new generation workers and leaders. This stable relationship makes workers believe that as long as they maintain good safety behaviors, they will be recognized, respected, and have opportunities for career development in the long term. This anticipated long-term benefit encourages them to internalize safety behaviors as part of their work habits, rather than merely performing surface-level behaviors for short-term rewards.

-

2)

In studying the impact of inclusive leadership on the safety behavior of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers, it was found that safety self-efficacy plays a mediating role; this discovery represents the first attempt to unveil the “black box” between inclusive leadership and safety behavior, enriching the understanding of the relationship between leadership style and employee safety behavior. At the same time, we responded to Jiang’s13call, suggesting that inclusive leadership influences employee behavior through their sense of efficacy. Traditional research has mainly focused on the direct impact of leadership behavior on employee safety behavior, while this study reveals the underlying mechanism: inclusive leadership not only encourages adherence to safety regulations through direct instructions or supervision but also indirectly influences safety behavior by enhancing employees’ safety self-efficacy. This provides a new interpretive perspective on how inclusive leadership can effectively promote employee safety behavior. First, safety self-efficacy reflects an individual’s judgment and confidence in their ability to complete safety tasks in specific situations. In high-risk environments like high-altitude railway construction, the level of safety self-efficacy directly influences decision-making and actions when facing complex situations. This study clarifies its bridging role between inclusive leadership and safety behavior, providing theoretical support for using social cognitive theory to explain and improve employee safety behavior in complex and high-risk work environments. Second, the triadic reciprocal causation in social cognitive theory indicates that safety self-efficacy is not isolated but is influenced by the environment created by inclusive leadership and, in turn, affects safety behavior. This further emphasizes the need to consider the interplay between individual, environment, and behavior when studying individual actions. Finally, this research offers a valuable example of interdisciplinary integration for psychology, management, and safety science, applying social cognitive theory from psychology to the field of safety management, revealing the relationships among inclusive leadership, safety self-efficacy, and safety behavior, and promoting communication and collaboration among different disciplines. This provides a more comprehensive and in-depth theoretical foundation for addressing practical safety management issues and advances the joint development of related disciplines.

-

3)

Based on the theory of organizational personification, this study explores that perceived organizational support not only plays a positive moderating role in the relationship between inclusive leadership and the safety behavior of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers but also plays a key role in the impact of inclusive leadership on safety self-efficacy. This exploration not only contributes a new theoretical perspective to the academic research in organizational behavior, leadership theory, and safety management but also provides empirical evidence for understanding and enhancing employee safety behavior and self-efficacy in extreme work environments. First, this finding enriches our understanding of the relationship between organizations and employees. It suggests that the support provided by the organization is not merely a simple resource provision but can play a moderating role in the interaction between leaders and employees. For railway construction workers in harsh high-altitude environments, this perceived support can enhance their sense of identification and belonging to the organization, thereby affecting their safety behavior and self-efficacy. Second, from the perspective of inclusive leadership, this study expands the boundaries of its effects. Previous research on inclusive leadership has mainly focused on its direct impact on employees, while this view reveals that under the moderation of perceived organizational support, the effects of inclusive leadership can be further enhanced. This provides new ideas for optimizing leadership strategies, emphasizing the importance of the interplay between organizational support and leadership style. Finally, on the psychological level of employees, this conclusion deepens the understanding of the formation mechanism of safety self-efficacy. The positive moderating effect of perceived organizational support means that when employees feel cared for by the organization, they are more confident in facing safety challenges at work, which enhances their self-efficacy. This provides a theoretical basis for promoting employees’ psychological well-being and positive work attitudes.

Practical implications

This study provides several practical insights for enhancing the safety behavior of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers.

-

1)

Research results indicate that inclusive leadership positively shapes the safety behavior of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers. Therefore, during high-altitude railway construction, it is essential to focus on the development and shaping of leaders. This can be achieved through specialized leadership training, allowing leaders to deeply understand the core principles of inclusive leadership, enhance self-awareness, and eliminate potential biases. Senior leaders should also set an example by demonstrating the charm of inclusive leadership through their actions, serving as a role model for managers at all levels. Additionally, an effective supervision and evaluation mechanism should be established to ensure continuous improvement and optimization of leadership styles towards more inclusivity. On the other hand, creating an environment and atmosphere conducive to inclusive leadership is crucial. Clear and stringent inclusion policies and guidelines should be formulated to convey a firm zero-tolerance stance against discrimination and exclusion. An open and diverse communication platform should be established, ensuring that construction workers can freely express their opinions and needs and receive timely and effective responses, whether through formal meetings or convenient online communication tools. When forming teams, diversity should be considered, and support and understanding should be provided to workers, so that new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers can work comfortably in an inclusive and supportive environment.

-

2)

Research results highlight the mediating role of safety self-efficacy in the relationship between inclusive leadership and the safety behaviors of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers. Therefore, enhancing construction workers’ safety self-efficacy is beneficial for improving their safety behavior levels. To improve construction workers’ safety self-efficacy, we should first focus on the training and education of new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers. Through systematic and targeted safety training programs, we can impart specialized safety knowledge and skills, helping them understand potential risks in the construction process and appropriate responses. This training not only enhances their theoretical understanding but also improves their ability to handle crises in practical situations, gradually building their confidence in their own safety assurance abilities, that is, their safety self-efficacy. Secondly, it is essential to establish a positive feedback mechanism and effective incentive system. During construction, providing timely recognition and encouragement for correct safety behaviors, and offering constructive criticism and guidance for errors or inappropriate actions, is crucial. This clear and prompt feedback allows workers to recognize the quality of their own behaviors, make adjustments and improvements, and feel that their efforts and contributions are valued and acknowledged. This, in turn, stimulates their motivation and confidence to further enhance their safety performance. Finally, creating a positive safety culture is also a vital guarantee for improving safety self-efficacy. Promoting a safety-first value within the entire construction team ensures that every member deeply understands the importance of safety. Through internal communication and collaboration, new-generation construction workers can feel the collective pursuit and effort towards safety, thereby subtly reinforcing their belief in their own ability to ensure safety and encouraging proactive safety behaviors.

-

3)

Research results also emphasize the moderating role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between inclusive leadership and safety self-efficacy and safety behaviors. Therefore, in practical management, it is crucial not only to focus on the cultivation of inclusive leadership but also to enhance the perception of organizational support among new-generation high-altitude railway construction workers. On one hand, the organization should establish an efficient and transparent information platform to timely communicate policies, standards, and the latest technological requirements related to construction safety to the workers. Additionally, sharing progress updates, encountered problems, and solutions for the construction projects will help workers understand the importance and value of their roles in the overall project. Regular safety experience exchange activities should also be organized to encourage workers to share safety insights and success stories, facilitating mutual learning and growth. Through comprehensive information sharing, workers can feel the organization’s trust and respect, thereby enhancing their perception of organizational support. On the other hand, increasing humanistic care is also an important aspect of improving perceived organizational support. Given the harsh conditions of high-altitude railway construction, the organization should pay attention to the physical and mental health of the workers. Providing regular medical check-ups and psychological counseling services to identify and address potential health issues promptly is essential. In terms of living conditions, offering a comfortable living environment and diverse recreational activities can help alleviate their work-related stress. When workers face difficulties, the organization should offer timely help and support to make them feel warmth and care. Additionally, sending warm greetings and condolences during special holidays and workers’ birthdays can strengthen their sense of belonging. Through these humanistic care measures, new-generation construction workers will genuinely experience the organization as a solid support, thus enhancing their perception of organizational support.

Limitations and future research

Although every effort has been made to ensure the objectivity and scientific validity of the research, there are still some limitations. First, due to constraints such as research costs and time, a cross-sectional survey was used, which may introduce some bias in the data. Therefore, future research will aim to expand the sample size and use longitudinal study methods to further validate the model’s validity. Second, the current study only considered the mediating role of safety self-efficacy and the moderating role of perceived organizational support. Future research could explore the role of other variables in the impact of inclusive leadership on safety behaviors, thereby further enriching the research model framework.

Conclusions

This study is based on social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, and organizational personification theory to better understand the mechanisms through which inclusive leadership affects the safety behaviors (safety compliance and safety participation) of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers. Firstly, the research indicates that inclusive leadership has a significant positive direct impact on the safety behaviors (safety compliance and safety participation) of these workers, and it also indirectly affects their safety behaviors through safety self-efficacy. Secondly, the study shows that perceived organizational support enhances the relationship between inclusive leadership and both safety self-efficacy and safety behaviors (safety compliance and safety participation), with perceived organizational support playing a more substantial facilitating role in the influence of inclusive leadership on safety self-efficacy. Therefore, these findings suggest that improving leaders’ inclusiveness, enhancing employees’ safety self-efficacy, and creating a supportive organizational environment to boost employees’ perception of organizational support can significantly improve the safety behaviors of the new generation of high-altitude railway construction workers and substantially reduce the occurrence of safety accidents.

Data availability

All data, models, or code generated or used during the study are available from the first author by request.

References

China SCotPsRo. Circular on the issuance of the 14th Five-Year plan for the development of a modern comprehensive transportation system. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2022−01/18/content_5669049.htm (2022).

Lu, C. & Cai, C. Challenges and countermeasures for construction safety during the Sichuan–Tibet railway project. Engineering 5, 833–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2019.06.007 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Scientific problems and research proposals for Sichuan–Tibet railway tunnel construction. Undergr. Space 7, 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2021.10.002 (2022).

Leung, M. Y. et al. Impact of job stressors and stress on the safety behavior and accidents of construction workers. J. Manag. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000373 (2016).

Neal, A. & Griffin, M. A. Safety climate and safety behaviour. Aust. J. Manag. 27, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289620202701S08 (2002).

Clarke, S. Safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviours. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 86, 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2012.02064.x (2013).

Cheng, L. et al. The influence of leadership behavior on miners’ work safety behavior. Saf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104986 (2020).

Smith, T. D. et al. Safety-specific transformational and passive leadership influences on firefighter safety climate perceptions and safety behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 86, 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.02.019 (2016).

Shen, Y. et al. The impact of transformational leadership on safety climate and individual safety behavior on construction sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010045 (2017).

Jiang, L. et al. Contingent reward transactional leaders as good parents: Examining the mediation role of attachment insecurity and the moderation role of meaningful work. J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9553-x (2019).

Ågotnes, K. W. et al. Daily work pressure and exposure to bullying-related negative acts: The role of daily transformational and laissez-faire leadership. Eur. Manag. J. 39, 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.09.011 (2021).

Ryan, J. Inclusive leadership: A review. J. Educ. Adm. Found. 18, 92–125 (2007).

Jiang, J. et al. Inclusive leadership and employees’ voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 41, 6395–6405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01139-8 (2022).

Sedlářík, Z. et al. Needs before deeds: Psychological need satisfaction as a mechanism linking inclusive leadership to organizational citizenship behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 45, 51–63 (2024).

Zhang, G. & Zhao, W. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behavior–an intermediary model with moderation. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 45, 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2023-0287 (2024).

Yang, J. & Li, M. Construction characteristics and quality control measures under high altitude and cold conditions. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science Vol. 676. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/676/1/012109 (2021).

Mo, J. & Cui, L. The effect of proactive personality on the safety behavior of high-altitude railroad construction workers. Sci. Technol. Eng. 23, 12767–12774. https://doi.org/10.19713/j.cnki.43-1423/u.T20222311 (2023).

Umrani, W. A. et al. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behaviours: social exchange perspective. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06192-1 (2024).

He, B. et al. Inclusive leadership and subordinates’ pro-social rule breaking in the workplace: Mediating role of self-efficacy and moderating role of employee relations climate. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag.. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.487 (2021).

Epley, N. et al. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864 (2007).

Blau, P. M. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x (1964).

Mehmood, M. S. et al. Entrepreneurial leadership and employee innovative behavior: Intervening role of creative self-efficacy. Hum. Syst. Manag. 39, 367–379. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-190783 (2020).

Ullah, I. et al. Leadership styles and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The mediating role of self-efficacy and psychological ownership. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.683101 (2021).

Javed, A. et al. Sustainable leadership and employee innovative behavior: Discussing the mediating role of creative self-efficacy. J. Public Aff. 21, e2547. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2547 (2021).

Seers, A. Team-member exchange quality: A new construct for role-making research. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 43, 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90060-5 (1989).

Fugas, C. S. et al. Another look at safety climate and safety behavior: Deepening the cognitive and social mediator mechanisms. Accid. Anal. Prev. 45, 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.08.013 (2012).

Griffin, M. A. & Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.3.347 (2000).

Locke, E. A. et al. Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.125 (1981).

Ni, G. et al. Influencing mechanism of job satisfaction on safety behavior of new generation of construction workers based on Chinese context: The mediating roles of work engagement and safety knowledge sharing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 8361 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Stay or leave: influence of employee-oriented social responsibility on the turnover intention of new-generation employees. J. Bus. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113814 (2023).

Mo, J. & Wang, R. Early warning research on unsafe behavior of high altitude tunnel construction personnel based on HLM-BP. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.19713/j.cnki.43-1423/u.t20220739 (2023).

Kuknor, S. C. & Bhattacharya, S. Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 46, 771–797. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-07-2019-0132 (2022).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 (1977).

Bandura, A. & Wessels, S. Self-efficacy (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Katz-Navon, T. et al. Safety self‐efficacy and safety performance: Potential antecedents and the moderation effect of standardization. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 20, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860710822716 (2007).

Corbett, J. B. Motivations to participate in riparian improvement programs: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Sci. Commun. 23, 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554700202300303 (2002).

Rodgers, W. M. et al. Distinguishing among perceived control, perceived difficulty, and self-efficacy as determinants of intentions and behaviours. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 607–630 (2008).

Wang, X. Integrating the theory of planned behavior and attitude functions: Implications for health campaign design. Health Commun. 24, 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X248903 (2009).

Li, F. & Han, M. Comparative quality relations among the safety-specific transformational leadership, the safety-specific self-efficacy and the safety performance—an empirical research based on coking and chemical enterprise. Saf. Environ. 20, 1021–1027 (2020).

Sun, L. & Zhang, J. Influence of miners’ Self-Efficacy on unsafe operation behavior. Saf. Coal Mines 49, 237–240 (2018).

Mo, J. et al. Proactive personality and construction worker safety behavior: Safety self-efficacy and team member exchange as mediators and safety-specific transformational leadership as moderators. Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040337 (2023).

Rhoades, L. & Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 698 (2002).

Aselage, J. & Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Org. Psychol. Behav. 24, 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.211 (2003).

Umrani, W. A. et al. Inclusive leadership, employee performance and well-being: an empirical study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 45, 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2023-0159 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Leadership and follower voice: The role of inclusive leadership and group faultlines in promoting collective voice behavior. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 59, 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/00218863211035 (2023).

Sürücü, L. et al. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behaviors: A moderated mediation model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 44, 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-05-2022-0227 (2023).

Zare, E. Effect perceived organizational support on employees’ attitudes toward work. Sci. Ser. Data Rep. 4, 28–34 (2012).

Ajmal, A. et al. The effects of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards on employee attitudes; mediating role of perceived organizational support. J. Service Sci. Manag. 8, 461–470. https://doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2015.84047 (2015).

Sumardjo, M. & Supriadi, Y. N. Perceived organizational commitment mediates the effect of perceived organizational support and organizational culture on organizational citizenship behavior. Calitatea 24, 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 (2023).

Podsakoff, P. M. et al. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Psychological contract of safety and construction worker behavior: Felt safety responsibility and safety-specific trust as mediators. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002185 (2021).

Junior, J. H. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings (Macmillan, 1992).

Wang, H. & Chang, Y. Inclusive leadership and employee creativity: A moderated mediation model. J. Xiangtan Univ. Philos Soc. Sci. Ed. 43, 112–116. https://doi.org/10.13715/j.cnki.jxupss.2019.03.018 (2019).

Fang, Y. & Jin, H. An empirical study on the effect of inclusive leadership style on the performance of research teams in colleges and universities. Tech. Econ. 33, 53–57 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ. Res. Methods 4, 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004 (2001).

Eisenberger, R. et al. Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 7, 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917 (2020).

Hayes, A. F. Process: A versatile computational tool for observed variable moderation, mediation, and conditional process modeling. University of Kansas (2012).

Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002 (1992).

Xiong, H. X. et al. Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 20, 757. journal.psych.ac.cn/adps/EN/Y2012/V20/I5/757 (2012).

Shi-Man, L. et al. The impact of mindfulness on subjective well-being of college students: The mediating effects of emotion regulation and resilience. J. Psychol. Sci. 38, 889 (2015).

Hair, J. F. et al. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45, 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-883017-0517-x (2017).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all respondents and editors for their patient review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and L.C.; methodology, L.C.; software, L.C.; validation, J.M. and L.C.; formal analysis, L.C.; investigation, L.C.; resources, J.M.; data curation, L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, J.M.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, J.M.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Junwen, M., Libing, C. The influence of inclusive leadership styles on the safety behaviors of new generation high altitude railway construction workers. Sci Rep 15, 10706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95532-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95532-7