Abstract

To demonstrate that enoxaparin in the irrigation saline solution can effectively prevent intraoperative fibrin formation (IFF) during Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) surgery without compromising graft viability, visual recovery, or intraoperative safety. A “before-and-after” study was conducted, comparing the rate of IFF in a prospective cohort of DMEK cases treated with enoxaparin to a retrospective cohort without treatment. Donor cornea characteristics, surgical data, rebubbling rate, final endothelial cell density (ECD), and best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) were analyzed. A total of 265 cases were analyzed. The incidence of IFF was 5.43% in the cohort without enoxaparin and zero in the enoxaparin-treated cohort. The risk ratio for enoxaparin use was 0 (confidence interval: 0), with a risk difference of -0.054 and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 18.42 cases to prevent one IFF event. No significant differences were found in baseline patients features or surgical aspects. The rebubbling rate was 16.98%, with no statistically significant difference between groups. No significant differences were observed in final ECD or BCVA between groups. In addition, no intraoperative complications or intraocular bleeding occurred with enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin is a safe, effective, and cost-efficient prophylaxis for preventing IFF during DMEK surgery. It impedes the development of IFF, which may require a new and costly transplant when it occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is the elective surgery for corneal endothelial decompensation. It offers several advantages over other procedures, such as superior visual recovery and longer graft survival1. Recently, the technique has been standardized, contributing to its widespread adoption2,3,4. Nevertheless, DMEK remains as a challenging surgery, with graft orientation, unscrolling and corneal adhesion being the essential steps.

Intraoperative fibrin formation (IFF) is an unpredictable and severe complication which occurs in 4.2–7.1% DMEK surgeries, and this has been related with early transplant failure. It impedes the unrolling and graft positioning during surgery turning a routine procedure into a prolonged operation5,6,7. Although IFF has been related to systemic anticoagulant prior DMEK, intraoperative bleeding or longer surgical manipulations, the pathogenesis remains unclear5,6,7.

Current treatments for IFF during DMEK include the intraoperative use of intracameral fibrinolytics such as recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA)5,8, similar to treatments used in toxic anterior segment syndrome after cataract surgery9,10. Unfortunately, despite early intervention with r-tPA, outcomes after IFF event are often poor, with up to 80% of cases requiring a new keratoplasty6. Despite its severity and frequency, no preventive strategies for IFF have been thoroughly explored.

Based on its previous use in paediatric cataract patients to reduce inflammatory reactions and fibrin formation9,10 we hypothesize that adding enoxaparin to the irrigation saline solution during DMEK surgery may effectively prevent IFF without compromising graft viability or impairing postoperative visual recovery.

Methods

This study involved human participants, was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board at Ramón y Cajal University Hospital (registration number 265/24) and was conducted in the accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study. The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study design and participants

A “before-and-after” study was conducted11. These studies compare the outcomes of a prospective cohort with a retrospective control group. We collected eye, surgery and clinical data on all the patients who underwent DMEK surgery at the Cornea unit of the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) from 2020 to 2023. These patients formed the historical control group and they were operated on without enoxaparin in the balanced salt solution (BSS, Alcon, Texas, USA) used for irrigation.

The prospective cohort consisted of consecutive patients who underwent DMEK with enoxaparin in the irrigation saline solution at Ramón y Cajal University Hospital (Madrid, Spain), Cruces University Hospital (Barakaldo, Spain) and La Mancha Centro Hospital (Alcazar de San Juan, Spain) from January to July 2024. All surgeons had more than five years of DMEK experience and had performed over the 25 cases proposed as the learning curve12.

Surgical technique and postoperative management

The decision to proceed to DMEK was based on the presence of suboptimal visual function due to corneal edema. The surgeries were performed by five experienced cornea surgeons (FA, DMB, PAP, JC, JE).

Patients underwent the standardized DMEK technique described in previous studies13. Laser YAG inferior iridotomy was performed at least one-month prior surgery. If cataract coexisted with corneal edema, phacoemulsification (Centurion phacoemulsifier, Alcon, Texas, USA) and monofocal intraocular lens implantation were performed prior to descemetorhexis (phaco-DMEK). Femtosecond laser was used for endothelial scoring according to surgeon´s preferences (Victus, Bauch and Lomb, Germany). DMEK scroll was loaded into Geuder injector (Geuder AG, Heidelberg, Germany) with endothelium facing outward. This was injected into the anterior chamber and unrolled using gentle taps on the cornea and BSS flushes into anterior chamber14,15.

In patients undergoing femto-DMEK, a femtosecond laser-assisted descemetorhexis of 8 mm was performed using the VICTUS FS laser platform (Bausch & Lomb, Dornach, Germany). The pachymetry line was adjusted to the thickest corneal point on the OCT image, and the following parameters were used: line spacing 2 μm, spot spacing 5 μm, energy 1.3 µJ, side cut angle 115°, top bonus − 500 μm, and arc length 360°.

Cases were excluded if postoperative follow- up was less than three months. Cases were not excluded from the study in the event of intraocular bleeding or iris pigment dispersion during DMEK.

Enoxaparin

In the prospective multicentre study group, enoxaparin 40 mg (Clexane, Sanofi, Belgium) was diluted in 500 ml of BSS infusion bottle16,17. This enoxaparin- BSS was used for washing off the brilliant blue G and trypan blue stain (Membrane Blue Dual, Dorc, Zuidland, Netherlands) from the DMEK graft and for loading the scroll into the injector. During DMEK surgery it was mainly used for the aspiration of viscoelastic after descemetorhexis and anterior chamber flushes for graft unrolling. During phaco-DMEK procedures, the enoxaparin-BSS was also used during all the conventional maneuvers such as nucleus hydrodissection, phacoemulsification, cortex aspiration, capsular polishing and viscoelastic removal.

Clinical outcomes

We compared the incidence of IFF during DMEK procedures between two groups, one with enoxaparin diluted in BSS and the other without it. IFF was defined by the presence of visible fibrin strands in the anterior chamber and/or altered graft behavior, characterized by stiffness and resistance to unrolling. Donor age and donor cornea endothelial cell density (ECD) were compiled. Donor cornea ECD was measured with noncontact specular microscopy (Konan Specular Microscope, Konan, Irvine, California). Data including graft diameter, gas tamponade or intraoperative complications such as posterior capsule rupture were collected. Any postoperative need for re-bubbling was recorded and this was performed when a third of the graft was not attached to the recipient stroma.

Outcome measurements were performed three months post-surgery and included best- corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and ECD. BCVA was measured by using a Snellen letter chart and outcomes were converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution units (logMAR) for statistical analysis. ECD was assessed using noncontact autofocus specular microscopy (Topcon, Kyoto, Japan).

Eyes with prior surgery other than phacoemulsification (e.g., trabeculectomy, pars plana vitrectomy, lens-iris diaphragm instability or intraocular lens placed outside the capsular bag) were excluded. Patients with retinal diseases, glaucoma, severe corneal haze or any other ocular disease were excluded from the postoperative visual acuity analysis.

Statistical analysis

The demographic data are summarized as means and standard deviations for the continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for the categorical variables. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram plots. Student´s t-test was used for continuous variables, while Fisher´s exact test was employed for categorical data. Risk ratio and number needed to treat (NNT) were calculated to measure association between the use of enoxaparin and the incidence of IFF. The results were considered significant for two-sided p values < 0.05. The data analysis was performed using Stata (version 18.0, StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Results

The study population comprised 265 eyes. The retrospective control group without enoxaparin included 129 eyes from 115 patients from the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital. The prospective cohort, treated with enoxaparin, consisted of 136 eyes from 126 patients, comprising: 81 eyes from 75 patient at Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, 29 eyes from 26 patients at Cruces University Hospital, and 26 eyes from 25 patients at La Mancha Centro Hospital. Notably, 14 patients underwent surgery on both eyes, with one eye operated with enoxaparin and the other without.

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) was the most common indication for DMEK, followed by pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, failure of previous DMEK and failure of previous Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK). 9 patients had a mixture of endothelial diseases (3.39%) and were classified as other: 4 patients had endothelial failure in a penetrating keratoplasty, 2 had posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, one eye suffered from pseudoexfoliation syndrome, other had Chandler´s syndrome and the last had a history of herpetic endothelitis (Table 1).

Isolated DMEK surgery was more frequent than phaco-DMEK and SF6 gas was the preferred tamponade agent. However, the use of air tamponade Rose in the prospective cohort, resulting in a statistical difference between groups. We performed 15 cases of femtosecond laser-assisted DMEK procedures in the group without Enoxaparin and just 1 eye in the prospective cohort with Enoxaparin (Table 2). None of the patients who underwent femtosecond laser-assisted DMEK developed IFF reaction.

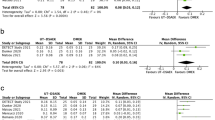

There were 7 IFF cases in the whole sample (2.46%); all of which occurred in the group involving DMEK without enoxaparin-BSS irrigation (5.43%). In fact, no cases were observed when patients were treated with enoxaparin-BSS (Table 3). Consequently, risk ratio for the use of enoxaparin diluted in BSS is 0 (confidence interval of 0), risk difference is -0.054 and the NNT to prevent an event of IFF is 18.42 cases. A post-hoc beta error calculation for our sample revealed a statistical power of 78.3% for an alpha error of 0.05.

The median age of patients whose surgeries were complicated by IFF was 62 years (range: 52–74) and 5 were females. Five patients suffered from FECD and two experienced pseudophakic bullous keratopathy. Four cases had isolated DMEK and three had phaco-DMEK. Three cases corresponded to FA surgeon (of 53 DMEK procedures performed without enoxaparin-BSS, incidence 5.66%), two to DMB (of 44 procedures, incidence of 4.55%) and two to PAP (of 32 procedures, incidence of 6.25%). Primary graft failure occurred in 6 cases, 5 of these underwent uncomplicated secondary DMEK, while another required an ultrathin- DSAEK. In the last case, following successful centering, orientation and application of the graft, fibrin strands were observed, and the patient was treated with intracameral r-tPA during surgery. Despite achieving satisfactory corneal clearing, the patient required a second intervention involving manual dissection of 360º peripheral anterior iris synechiae that were producing high intraocular pressure. None of the seven patients had been receiving anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy prior to surgery.

The rate of rebubbling as an early postoperative complication was similar in both study groups with no statistically significant difference. A post-hoc analysis of the risk ratio for the need for rebubbling, based on gas tamponade or if DMEK was performed isolated or combined with phacoemulsification, yielded results of 1.01 (95% confidence interval, 0.59–1.74) and 1.15 (95% confidence interval, 0.65–2.03), showing no statistical significance. The final BCVA (logMAR) were analyzed in 93 eyes treated with enoxaparin and 88 eyes without it. There was no statistically significant difference in BCVA between groups (Table 3).

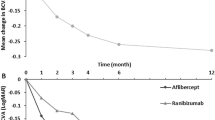

Intraoperative incidence of IFF, postoperative rate of rebubbling needs and final BCVA. P* = T- test, P # = Fisher´s exact test graft ECD before surgery was not similar between the two groups, being significantly lower in the group with Enoxaparin (Table 4). Due to insufficient follow-up of at least 3 months, as well as cases of primary graft failure or corneal opacity, only 109 eyes from the Enoxaparin group and 108 eyes from the non-enoxaparin group were included in the final analysis. There was an overall decrease in ECD of 1192.85 ± 558.47 cells/ mm2 (47.21%) after the DMEK surgery, however, the final ECD were similar and statistically not significant in both groups (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study evaluates the role of enoxaparin in preventing intraoperative fibrin formation (IFF) during Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK). Though infrequent, fibrin formation is a serious complication in ocular surgery. While extensively studied in cataract procedures, its management in DMEK has been less documented. Studies by Bostan et al.. and Benage et al.. reported incidences of 4.2% and 7.1% respectively, with a correlation to systemic anticoagulants5,7. The optimal management of IFF during DMEK surgery is not well established. Some authors argue that mechanical removal of fibrin strands is ineffective and carries the risk of graft damage5,6. Conversely, intracameral r-tPA has been suggested as an effective treatment in isolated cases of IFF5,8. However, any additional maneuvers prolong surgery and may compromise graft health. A preventive measure would therefore prove more desirable to avoid these risks.

Cataract surgery, particularly in paediatric patients, carries a higher risk of fibrin formation due to increased postoperative inflammation9,10. Various strategies have been explored to prevent these complications, with the coagulation cascade likely playing a role in fibrinoid inflammation. Enoxaparin diluted in BSS has been used in paediatric cataract cases, effectively reducing early inflammation, fibrin formation, and postoperative complications, without causing intraocular bleeding or a decrease in ECD16,17,18. Similarly, enoxaparin has shown efficacy in minimizing postoperative inflammation in adult diabetic cataract patients19.

Based on the success in cataract surgery, we hypothesized that enoxaparin could also prevent IFF in DMEK. We used 40 mg of enoxaparin diluted in 500 ml of BSS, a concentration that successfully reduced fibrin formation without impacting ECD or visual outcomes. Lower concentrations of enoxaparin (10 mg diluted in 500 ml of BSS) failed to prevent fibrin formation in paediatric cataract patients17.

In our study, enoxaparin effectively reduced IFF, with a risk ratio of zero and a number needed to treat of 18.42 patients. BCVA outcomes, ECD loss (47.21%) and rebubbling rates (16.98%) were comparable between the enoxaparin and non-enoxaparin groups, and aligned with findings from other large prospective series20. Whilst some studies have reported lower ECD loss during the first year12,21, others have shown similar reductions20,22. Nevertheless, comparisons of ECD across different populations should be interpreted with caution due to factors such as whether measurements were taken prior to or following graft preparation, image quality, and the time span between tissue harvest and implantation.

Enoxaparin is widely available, stable at room temperature, and conveniently packaged in subcutaneous pens, making it easy to inject into the irrigating BSS. It is both a time- and cost-efficient preventive measure, with a single syringe costing approximately €4. Even if up to 20 syringes are required (around €80) to prevent one case of IFF, this remains far more cost-effective than the estimated €8,800 cost of a corneal transplant in the event of graft failure due to IFF23.

Intraoperative bleeding has been identified as a risk factor for IFF, as it provides a substrate for coagulation and fibrin formation. Previous studies have reported a strong association between IFF in DMEK surgery and the use of systemic anticoagulants during the procedure5,7. However, in our study, none of the cases who developed IFF were receiving anticoagulants and these patients were younger (mean age of 62 years) than other series5,7, where anticoagulant use is less common. While enoxaparin administered into the bloodstream may increase the risk of surgical haemorrhage, in our scenario the drug is delivered into the anterior chamber. In our experience enoxaparin diluted in BSS does not increase perioperative intraocular bleeding, as described when used for paediatric cataract patients16,17,18,24. Although enoxaparin may extend intraocular bleeding once this occurs, it will prevent fibrin formation as it impedes the completion of the coagulation cascade. We did, for instance, perceive that enoxaparin- irrigation solution increases surface bleeding when incisions were made in vascularized corneas. However, this haemorrhage was subtle, did not enter the anterior chamber or compromise the surgery and, crucially, did not result in IFF.

Longer surgery, often involving anterior chamber shallowing and iris wobble, are typically associated with greater release of pigment or blood, which may contribute to IFF, particularly in the case of less experienced surgeons. Given that, since all the surgeons in our study were sufficiently experienced, we found no significant differences in IFF rates between the more and less experienced physicians. Femtosecond laser-assisted DMEK has not been associated with a higher rate of intraoperative complications²⁵, although its impact on IFF occurrence has not been specifically studied. In our study, there were only 16 cases of femtosecond laser-assisted DMEK, 15 of them in the group without enoxaparin, and none experienced IFF. Given these findings, femtosecond laser-assisted DMEK does not appear to be a relevant risk factor for intraoperative fibrin formation.

Interestingly, in two cases within our series, IFF occurred immediately following graft injection into the anterior chamber, without ocular decompression or surface tapping. Additionally, one patient with FECD experienced bilateral IFF in a straightforward case. IFF formation prior to graft manipulation has also been reported in 15 of 32 eyes in a previous case series7, suggesting the existence of a patient-related factor, independent of bleeding or surgical manipulation, that has yet to be identified.

The prevention of intraoperative fibrin formation (IFF) during DMEK is an emerging topic of interest in ophthalmology. A recently published study evaluated the use of enoxaparin in the irrigation solution during DMEK surgery, reporting no associated complications²⁶. However, there are significant methodological differences between that study and ours.

Firstly, the referenced study is retrospective and consists of a single cohort of DMEK patients who received enoxaparin, without a control group for comparison. This limits the ability to determine the true preventive effect of enoxaparin, as the absence of IFF cannot be directly attributed to its use without a comparative analysis. In contrast, our study includes both a prospective treatment group receiving enoxaparin and a retrospective control group without enoxaparin, allowing for a direct evaluation of its efficacy.

Secondly, while the previous study describes the usual postoperative evolution of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and endothelial cell density (ECD), it does not include a predefined sample size calculation to assess statistical differences. Our study, on the other hand, was designed with a specific power analysis to ensure meaningful comparisons between groups. Additionally, our findings allow for a cost-effectiveness evaluation, calculating the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent IFF, which provides valuable insights for clinical decision-making.

The study’s ‘before-and-after’ design ensures uniform data collection and planned measurements, making it less prone to missing data compared to retrospective cohorts11. However, this design introduces a potential limitation: comparing groups from different time frames may be affected by changes in procedure standardization and increasing surgeon experience over time. To mitigate this, we collected cases from the past 3 years and ensured that all surgeons had over 5 years´ experience, performing similar surgical techniques. Although we conducted a multicentre approach to expedite data collection, a prospective randomized trial would provide more robust findings.

In summary, enoxaparin is a safe and cost-effective method to prevent IFF during DMEK. While the findings are encouraging, larger, randomized studies are needed to further evaluate its efficacy and optimize treatment protocols.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Price, M. O., Kanapka, L., Kollman, C., Lass, J. H. & Price, F. W. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: 10-Year cell loss and failure rate compared with Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea 43 (11), 1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000003446 (2024).

Flockerzi, E., Turner, C. & Seitz, B. Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty is the predominant keratoplasty procedure in Germany since 2016: A report of the DOG-section cornea and its keratoplasty registry. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 108(5), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2022-323162 (2024).

Hoffmann, J. V. et al. Changing indications for keratoplasty: Monocentric analysis of the past two decades. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-024-06639-y (2024). Advance online publication.

Viberg, A., Samolov, B. & Byström, B. Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty versus Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: A National Registry-Based comparison. Ophthalmology 130(12), 1248–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.07.024 (2023).

Bostan, C. et al. Intracameral fibrinous reaction during Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Ocul Immunol. Inflamm. 32(8), 1682–1688. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2023.2287057 (2024).

Trinh, L., Bouheraoua, N., Muraine, M. & Baudouin, C. Anterior chamber fibrin reaction during Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 25, 101323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2022.101323 (2022).

Benage, M. et al. Intraoperative fibrin formation during Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 18, 100686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100686 (2020).

Ferguson, T. J., Traboulsi, E. I. & Goshe, J. M. Successful pediatric DMEK facilitated by intracameral tissue plasminogen activator to mitigate anterior chamber fibrin reaction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 19, 100812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100812 (2020).

Mehta, J. S. & Adams, G. G. W. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator following paediatric cataract surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 84(9), 983–986. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.84.9.983 (2000).

Osaadon, P. et al. Intracameral r-tPA for the management of severe fibrinous reactions in TASS after cataract surgery. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32(1), 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721211002064 (2022).

Sessler, D. I. & Imrey, P. B. Clinical research methodology 2: observational clinical research. Anesth. Analg. 121(4), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000000861 (2015).

Vasiliauskaitė, I. et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: Ten-Year graft survival and clinical outcomes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 217, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2020.04.005 (2020).

Arnalich-Montiel, F., Mingo-Botín, D., & Diaz-Montealegre, A. Keratometric pachymetric, and surface elevation characterization of corneas with fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy treated with DMEK. Cornea 38(5), 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001875 (2019).

Tenkman, L. R., Price, F. W. & Price, M. O. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty donor preparation: Navigating challenges and improving efficiency. Cornea 33(3), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000045 (2014).

Fogla, R. & Thazethaeveetil, I. R. A novel technique for donor insertion and unfolding in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 40(8), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002698 (2021).

Rumelt, S., Stolovich, C., Segal, Z. I. & Rehany, U. Intraoperative enoxaparin minimizes inflammatory reaction after pediatric cataract surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 141(3), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.020 (2006).

Çaça, I. et al. Effect of low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin) on congenital cataract surgery. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 5(5), 596–599. https://doi.org/10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.05.10 (2012).

Özkurt, Y. B., Taşkıran, N. E., Baran, A., Ömer, K. & Dog, K. Effect of heparin in the intraocular irrigating solution on postoperative inflammation in the pediatric cataract surgery. Clin. Ophthalmol. 3, 336–365. https://doi.org/10.2147/opth.s5127 (2009).

Ilhan, Ö. et al. The effect of enoxaparin-containing irrigation fluid used during cataract surgery on postoperative inflammation in patients with diabetes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 156(6), 1120–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2013.07.017 (2013).

Romano, V. et al. Combined or sequential DMEK in cases of cataract and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 102(1), e22–e30. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15691 (2024).

Dabrowska-Kloda, K., Olafsdottir, E., Stefanou, A. & Crafoord, S. DMEK surgery at a tertiary hospital in Sweden. Results and complication risks. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 1841–1849. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S429130 (2024).

Bichet, P. et al. Five-year clinical outcomes of 107 consecutive DMEK surgeries. PLoS One. 18(12), e0295434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295434 (2023).

Simons, R. W. P. et al. Trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) versus ultrathin Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (UT-DSAEK). Acta Ophthalmol. 101(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15280 (2023).

Vasavada, V. A., Praveen, M. R., Shah, S. K., Trivedi, R. H. & Vasavada, A. R. Anti-inflammatory effect of low-molecular-weight heparin in pediatric cataract surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 154(2), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.021 (2012).

Einan-Lifshitz, A. et al. Comparison of femtosecond laser-enabled descemetorhexis and manual descemetorhexis in descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 36(7), 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001217 (2017).

Mulpuri, L. et al. Intracameral Enoxaparin for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: a pilot safety study. Cornea 44(3), 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000003662 (2024).

Funding

This study has been funded by the project PI22/01252 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, with Francisco Arnalich-Montiel as the Principal Investigator (PI). Additionally, it has received support from RD21/0002/0018 RICORS – Inflammatory Diseases, within the Ophthalmology Group at Hospital Ramón y Cajal, led by Francisco Muñoz Negrete as the Principal Investigator (PI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D.A.P. performed surgeries, acquired the data, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.D.M.B; J.E.E and J.C. performed surgeries and collected data.M.S; C.G.T; M.T.M.D. collected the data.J.A.D.T. designed the study and interpreted the results.F.J.M.N. designed the study and interpreted the results and secured funding .F.A.M. performed surgeries, designed the study, supervised the research process, secured funding and wrote the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De-Arriba-Palomero, P., Mingo-Botín, D., Etxebarría-Ecenarro, J. et al. Effectiveness of enoxaparin in preventing intraoperative fibrin formation during DMEK assessed in a before-and-after study. Sci Rep 15, 15423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99324-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99324-x