Abstract

Malaria control faces challenges from widespread insecticide resistance in major Anopheles species. This study, employing a cross-species approach, integrates RNA-Sequencing, whole-genome sequencing, and microarray data to elucidate drivers of insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae complex and An. funestus. Here we show an inverse relationship between genetic diversity and gene expression, with highly expressed genes experiencing stronger purifying selection. Gene expression clusters physically in the genome, revealing potential coordinated regulation, and we find that highly over-expressed genes are associated with selective sweep loci. We identify known and novel candidate insecticide resistance genes, enriched for metabolic, cuticular, and behavioural functioning. We also present AnoExpress, a Python package, and an online interface for user-friendly exploration of resistance candidate expression. Despite millions of years of speciation, convergent gene expression responses to insecticidal selection pressures are observed across Anopheles species, providing crucial insights for malaria vector control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria remains a leading cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality, resulting in an estimated 619,000 deaths in 20211. Insecticide-based vector control interventions are the most successful tools for reducing malaria incidence, responsible for over 80% of the malaria cases averted between 2000 and 20152; however, the gains made in malaria control have plateaued in the last eight years and cases are beginning to rise1. The reversal of gains is partially due to widespread insecticide resistance within populations of the anopheline mosquito vector3, reducing the efficacy of insecticide-treated bed neds (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), the two primary malaria intervention tools1,4.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, four mosquito species are responsible for the majority of malaria transmission, the An. gambiae species complex (An. gambiae, An. arabiensis, and An. coluzzii) and An. funestus5,6,7. Understanding the similarities and differences in resistance mechanisms between the different dominant vector species is critical to inform malaria mitigation strategies, which are mostly employed indiscriminately despite differences in vector composition between and within areas of sub-Saharan Africa.

Sharing of resistance mechanisms between insects is commonly observed; mutations at the insecticide target site genes Rdl, Kdr and Ace-1 occur at equivalent codons throughout arthropods8,9, and insecticide detoxification is often driven by cytochrome P450s from the insect CYP6 family10; this may occur through parallel evolution, or in closely related insects, introgression, where genetic material is passed between species via hybridisation. Although adaptive introgression is seen at resistance loci within the An. gambiae species complex11,12, there is no evidence of hybridisation or introgression with An. funestus, which diverged approximately 80 million years ago13,14.

Insecticide resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes commonly involves large gene families, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), carboxylesterases (COEs), and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UDPs)15,16,17. Upregulation of key P450s has been reported in insecticide resistant populations of each Anopheles species, for example CYP6Z1, CYP9K1, CYP6AA1 and CYP6P9a in An. funestus18,19,20; CYP9K1, CYP6AA1, CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii21,22,23; and CYP6P4 in An. arabiensis24. Similarly, cuticular resistance25, which involves thickening and modification of the composition of the cuticle, slowing the rate of absorption of insecticides has been reported in both An. gambiae s.l26 and An. funestus27. Work comparing distinct Anopheles species found that gene numbers within these families were similar across species but lineage-specific losses and gains are regularly observed14. Despite these similarities, differences between the An. gambiae species complex and An. funestus are also observed. A prominent example is single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the target site of insecticide, which reduce the efficacy of insecticides through changes to binding affinity. The two best studied are Kdr and Ace-128,29, both of which are found in the An. gambiae species complex, but which are seemingly absent in An. funestus. Novel mechanisms of resistance have also recently been discovered, including the direct binding of pyrethroids by chemosensory proteins (CSPs)30, as well as evidence for a role of both hexamerins, α-crystallins31. The recent discovery of such mechanisms highlights the complexity of resistance and the need for further study into molecular mechanisms of resistance in major malaria vectors.

A plethora of ‘omics data has now been generated for malaria vectors. Over the past two decades, transcriptomic studies have driven discoveries into mechanisms of insecticide resistance, first in the form of microarrays, and subsequently RNA-Sequencing. In addition, since publishing the first phase of the Anopheles 1000 genomes project in 201732, the MalariaGEN Vector Observatory has generated and made public thousands of high-quality whole-genome sequences of major malaria vectors from throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Although individual -omics experiments have had great success in identifying highly over-expressed transcripts involved in resistance, these studies result in thousands of differentially expressed genes resulting from noise from the susceptible comparator. Previous work has successfully used microarray data in exploratory analyses to identify patterns of gene expression across the An. gambiae species complex, identifying meta-signatures across geographically and temporally disparate data, highlighting the importance of meta-analyses30,31,33. In this study we characterise gene-expression profiles from published transcriptomic studies across two malaria vector complexes and establish relationships with whole-genome sequence data. To achieve this, we explored expression in resistance candidate genes and protein-coding families across 28 individual experiments of An. gambiae s.l and An. funestus34,35,36,37,38,39,40. These data have been integrated both with the previous microarray meta-analysis31 and with whole-genome sequence data from the Anopheles 1000 genome project32. The meta-analysis performed here has been made available as a resource to the community as a user-friendly python package, AnoExpress, combined with convenient interactive notebooks intended to be run in Google Colaboratory.

Results

AnoExpress

We performed a differential expression meta-analysis on read count data from 28 RNA-sequencing datasets representing insecticide-resistant Anopheles populations from 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa34,35,36,37,38,39,40 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Twenty-eight resistant populations were included in this study from An. coluzzii (n = 15), An. gambiae (n = 3) An. arabiensis (n = 5) and An. funestus (n = 5). Read-count data from different species were derived from aligning to each respective reference genome assembly. For differential expression analysis, each resistant population was compared to an insecticide-susceptible strain of the same species from the same study with DESeq2. As read-counting methods differed between published studies, we first performed an experiment with RNA-Sequencing data from Nagi et al., (2023)41 to ensure that fold-change data derived from these methods would be comparable. We compared three read-counting methods, HISAT2-featurecounts, HISAT2-htseqcount, and Kallisto, and found high pearsons R correlations of log2 fold-change values between methods (all > 0.922) (Supplementary Text 1, Supplementary Table 2). Next, to ensure that different methodologies such as fragment vs read count did not significantly influence the results, we performed a correlation test (Supplementary Text 1, Supplementary Fig. 1) and found extremely high correlations of both differentially expressed genes (0.9667) and normalised counts (0.9997). To enable cross-species comparison of putative resistance genes, we located orthologs between each different genome assembly and the AgamP4 PEST reference genome, using the OrthoMCL algorithm in VectorBase. As the inclusion of each successive assembly reduces the numbers of genes that are present, we provide four differential expression analyses; the full dataset, termed ‘gamb_colu_arab_fun’ (8599 genes), and secondary analyses – ‘gamb_colu_arab’ (8651 genes), ‘gamb_colu’ (11,288 genes), ‘fun’ (14,176 genes). Analyses herein were performed on the full gamb_colu_arab_fun dataset unless specified.

Different colours show different species. Sample sites with multiple colours indicate multiple species comparisons at that location. Information on the susceptible comparator species is available in Supplementary Table 1. The map is open source and is produced with geopandas, contextily, cartopy and inkscape.

These data are presented within a python package, AnoExpress, made for the community, with example notebooks provided to run in Google Colab. Users can load, explore, and visualise the gene expression meta-analysis data, including reproducing most analyses presented herein. AnoExpress can also directly load gene expression data from an earlier meta-analysis of microarray data31. AnoExpress is located here: github.com/sanjaynagi/AnoExpress. Documentation and a video user-guide are provided to improve ease of access.

Dataset structure

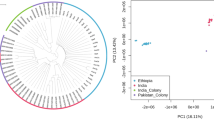

To investigate overall structure in the dataset, we performed principal components analysis on both the count and fold-change data. PCA on the log-transformed count data revealed five distinct clusters present. Four clusters contain samples only from An. funestus, An. coluzzii, or An. arabiensis, with a fifth cluster containing a mixture of An. gambiae, An. arabiensis and An. coluzzii (Fig. 2A). The four species did not resolve into four distinct clusters, suggesting that batch effects from different studies could be present. We therefore only performed within-study differential expression analysis. To compare RNA-Sequencing data with the earlier microarray studies, we performed a PCA on the fold-change data from all available experiments (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Figs. 2A-C). There was no evidence of clustering between the two technologies, suggesting that the results between the two methodologies are comparable and can be used in combined analyses.

A A principal components analysis of normalised log2 read count data from the AnoExpress differential expression meta-analysis. An. gambiae = orange, An. coluzzii = blue, and An. arabiensis = green. B Per-gene correlations of normalised log2 read count data between species. C A histogram of mean pearsons R values of log2 fold change between neighbouring genes, from 1000 random permutations of genome position, with the true value plotted as a dashed vertical line.

Correlations between pairs of orthologous genes count data from different species were high, with lower correlation between An. funestus and the other three species, which is to be expected given their considerable divergence time (Fig. 2B).

Gene expression is physically clustered in the genome

As changes in gene expression are likely to be related to cis-acting factors and the local genetic context42, genes in close physical proximity are more likely to show similar patterns of expression. To test this within our dataset, we calculated and averaged the Pearson’s correlation on log2 fold-changes between each neighbouring gene in the dataset, resulting in a mean Pearson’s R of 0.10 for neighbouring genes. To determine whether this value was higher than expected based on chance, we randomly permuted the positions of all genes in the genome 1000 times and re-calculated the mean Pearson’s R for now neighbouring genes. Figure 2C shows the histogram of mean Pearson’s correlations, demonstrating a clear effect of genome proximity on gene expression.

To further explore physical clustering of resistance-related gene expression, we visualised fold-change values across the whole genome. In Fig. 3, we use AnoExpress to plot gene expression for all genes across all comparisons in the gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis and calculate the moving average log2 fold change across the genome in sliding windows. We identify gene clusters known to be associated with insecticide resistance, such as the CYP6P, CYP9K, CYP6M/Z and GSTD gene clusters. This analysis also highlighted numerous clusters of cuticle proteins which show elevated expression.

Expression for all genes in the gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis is plotted against the An. gambiae PEST reference genome. Different colours represent different species – blue = An. coluzzii, orange = An. gambiae, green = An. arabiensis and red = An. funestus. A moving average of gene expression is plotted as a black line, calculated in sliding windows of 10 genes, with a step of 2 genes. The Y-axis is truncated between -8 and +10 log2 Fold-change to ease interpretation. Signals in close proximity to known, or putative, IR loci are labelled and highlighted with dashed grey lines. Gene density is displayed below the x-axis. In AnoExpress, plots are interactive, aiding interpretation.

Genetic diversity and purifying selection scale with levels of gene expression

We postulated that genes showing higher levels of absolute expression are more likely to be functional in multiple tissues or pathways, and so should be highly conserved, experiencing the highest levels of purifying selection. We integrated whole-genome sequence data from the Anopheles 1000 genomes project32, to explore the relationship between gene expression and genetic diversity, for each species in which genomic data was publicly available. To compare between species, we selected representative cohorts of each species from across the species’ range; An. gambiae from Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda), An. coluzzii from Burkina Faso, Cote D’Ivoire, and Kenya), and An. arabiensis from Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Uganda), collected between 2012 and 2019. These cohorts show no signatures of inbreeding or major demographic events. As a measure of absolute expression, we used normalised count data. We then counted the number of segregating sites of synonymous and non-synonymous mutations, as well as calculating nucleotide diversity, π, in each gene, for each species.

Figure 4 shows the ratio of pN/pS and nucleotide diversity, for various levels of expression binned into 5% percentiles for the gamb_colu_arab analysis. We show that average nucleotide diversity is reduced for the most highly expressed genes and is lower overall in An. arabiensis compared to An. coluzzii and An. gambiae, which fits with expectations on genetic diversity from the literature43.

A The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous segregating sites (pN/pS) in An. coluzzii = blue, An. gambiae = orange, and An. arabiensis = green, at different levels of gene expression. B) Nucleotide diversity, π, calculated across the entire length of a gene. Levels of gene expression are based on median log2 counts from the gamb_colu_arab analysis.

We show that for each species, the pN/pS ratio is lower for the most highly expressed genes compared to lowly expressed genes. This holds more strongly in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii than An. arabiensis, which likely relates to the efficiency of purifying selection depending on population size—the effects of purifying selection are expected to be stronger in larger populations.

Highly overexpressed genes are associated with selective sweeps in wild-caught mosquitoes

Given that insecticide resistance is often associated with increased expression of metabolic genes and that beneficial resistance mutations can cause selective sweeps which spread through a population, we hypothesised that highly expressed genes are more likely to be found in proximity to genomic regions under selection in wild-caught mosquitoes.

To determine this, we investigated genome-wide signals of recent selection using the H12 statistic44 on data from phase 3 of the Anopheles 1000 genomes project (Nagi et al., in prep). Every signal was then mined to determine which genes in the AgamP4 assembly, if any, lie at the location of the peak of a selection signal. Further information on genome-wide selection scans and signal calling is found in Supplementary Text 2. Candidate genes were then defined as those genes showing a median fold-change of greater than two in the An. gambiae, An. coluzzii and An. arabiensis dataset (gamb_colu_arab), as these three species are represented in the Ag1000G phase 3 data32. We additionally filtered out lowly expressed genes (median counts < 5). After filtering, 106 candidate genes remained, of which 34 were located at the site of a signal of selection (Supplementary Table 3). Figure 5 displays the location of these genes in the An. gambiae PEST reference genome, and recovers known insecticide resistance candidates such as CYP6P3, CYP6M2, GSTE2 and CYP9K1, as well as numerous other genes putatively involved in resistance.

To determine whether this was a significant enrichment of genes compared to random chance, we carried out a permutation analysis. In 10,000 permutations, only two equalled or exceeded the value of 34 (p-value = 0.0002), suggesting that regions of the genome under selection are indeed enriched for the most highly overexpressed genes. Separately, we utilised the entire dataset of genes and found a positive association between a genes’ median fold-change and whether it was found at the site of an H12 selective sweep signal (pGLM = 0.000).

Signatures of resistance-associated gene expression

To explore highly over-expressed genes across all four species, we ranked genes by mean and median log2 fold change across all experiments (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Included in the over-expressed set (cut-off of fold change >2, median counts >5), are 65 and 78 genes respectively. Within these lists, the known pyrethroid metaboliser CYP6P345 (the ortholog of CYP6P9a/b in An. funestus) had a median and mean fold change of >6.8, demonstrating the utility of the meta-analytic approach. Included in both lists were other cytochrome P450s including CYP6P4, CYP9K1, CYP6M2, CYP6Z2, CYP6Z3 and CYP6P5, all of which have previously been linked to pyrethroid resistance across both species21,22. Interestingly, CYP4H17 which has never been explored for a role in pyrethroid resistance, appears 7th (mean) and 11th (median) with a median fold change of 3.47. Similarly appearing high across both mean and median rankings are cuticular related proteins CPLCG4, CPR150 and CPLCA3, a venom allergen (AGAP006417), an alkaline phosphatase (AGAP001684), gustatory receptor 49 (AGAP001169) and a protein with no known function (AGAP009327). In total, 50 genes are present in both the median and mean over-expressed sets including one carboxylesterase, eleven cytochrome P450s, three glutathione-S-transferases and one UGT from the major detoxification enzyme families (Fig. 6A). Additionally, nine cuticular proteins, one D7 salivary gland protein and two hexamerins are present from gene families previously linked to resistance31,46. Two genes related to odorant or taste detection are also present.

A Top genes based on the intersection of genes with mean and median fold-change as above 2, filtered for lowly expressed genes. Ag: An. gambiae, Ac: An. coluzzii, Aa: An. arabiensis, Af: An. funestus. B Consistently over-expressed genes. Genes that show significant (p < 0.05) and positive log2 fold-changes in more than 19 out of 28 experiments. C Most down-regulated genes based on median-fold changes. D Most consistently down-regulated genes. Genes that show significant and negative log2 fold-changes in more than 19 out of 28 experiments. E Significant GO terms and PFAM domains from gene set enrichment analysis (hypergeometric test) for the top 5% of overexpressed genes based on median fold-changes. Green shows up-regulation of genes whilst purple shows down-regulation, intensity shows relative levels of differential expression.

We then performed gene set enrichment analysis on the top 5% of overexpressed genes based on median fold-changes (419 genes) (Supplementary Table 4). We performed enrichment on both GO terms and protein (PFAM) domains; significant enrichment terms are displayed in Fig. 6D, categorised by broad resistance mechanism. In expectation with known gene families involved in insecticide resistance, we observe highly significant enrichment for many GO terms relating to detoxification, such as oxidoreductase activity (fdr-corrected p value = 8e-16), iron ion binding (p = 4.75e-15), heme-binding (p = 6.8e-14), monoxygenase activity (p = 9e-14), glutathione activity (p = 0.001) and glutathione metabolic process (p = 0.001), and the ‘P450’ (p = 1.6e-16), ‘GST_N_3’ (p = 0.002) and ‘GST_C’ (p = 0.004) protein domains. In addition, cuticular-related genes were also enriched, with the GO terms structural constituent of cuticle (p = 1.1e-23), chitin binding (p = 2.3e-09), chitin metabolic process (p = 1.3e-8), fatty acid elongase activity (p = 0.04), and the protein domains ‘Chitin_bind_4’ (p = 3.2e-20), ‘CMB_14’ (p = 1.3e-18), and CPCFC (p = 0.03). Finally, a large group of terms were related to sensory perception, including the GO terms ‘sensory perception of smell’ (p = 1.4e-6), odorant binding (p = 2.4e-6), olfactory receptor activity (p = 0.0002), sensory perception of taste (p = 0.018), taste receptor activity (p = 0.04), and the protein domains ‘7tm_6’ (p = 0.00003) and ‘7tm_7’ (p = 0.03), which indicate odorant and gustatory receptors.

We then explored highly down-regulated genes based on median fold-changes (Fig. 6C). Amongst the most down-regulated genes was CYP307A1, a known regulator of ecdysone synthesis47. In addition to hormone related transcripts CLIPA13 and Galectin 6 are heavily down-regulated. Zero GO terms were enriched based on the 5% lowest median fold-changes. If we instead use the 5% lowest mean fold-changes, we observe significant enrichment for sodium channel activity (p = 0.00013), sodium ion transport (p = 0.00059) and sodium ion transmembrane transport (p = 0.0044) the target sites for pyrethroids.

Consistently differentially expressed genes

We then explored genes which were significantly up and down-regulated most consistently.After filtering genes with very lowly expressed genes, only two genes were upregulated in 22 out of 28 RNA-Sequencing experiments, CYP6P3 and CYP9K1. GSTD3 and CYP6P4 were upregulated in 21 out 28. Figure 6B shows all 18 genes significantly over-expressed in at least 19 out of 28 experiments, and includes CYP4H17, CYP4H18, CYP6M2, GSTE2, a UGT and a trypsin TRYP4 (Supplementary Table 5). This set of genes were enriched for seven P450-related GO terms, including oxidoreductase activity (p = 1.68e-09) and heme binding (p = 5.66e-09), and the PFAM domain ‘p450’ (p = 9.19e-10).

In contrast, only eight genes showed consistent down-regulation in at least 19 out of 28 experiments (Supplementary Table 5), including two opsin genes, GPROP4 and GPROP6, and a molecular chaperone HtpG gene (AGAP006961). The genes are enriched in seven GO terms relating to light detection, such as photoreceptor activity (p = 0.029), visual perception (p = 0.029) and phototransduction (p = 0.039).

Detoxification genes

Twenty-four genes from the P450, GST and carboxylesterase families show either a median or mean fold change of >2 (Supplementary Table 6). Eighteen of those genes were cytochrome P450s, and nine P450s are significantly upregulated in at least 19 out of 28 of all datasets. The cytochrome P450 family most represented is the CYP6 family, orthologous to the CYP3 clade in humans, responsible for the vast majority of xenobiotic metabolism. The CYP6Ps, CYP6M2 and CYP9K1 which have been repeatedly associated with insecticide resistance are all heavily implicated and are located in regions of the genome under selection (Fig. 5). Additionally, four members of the CYP4 family appear to be overexpressed across multiple resistant populations, particularly CYP4H17, but also CYP4H16, CYP4H18, and CYP4C28.

Similarly, four out of 27 GSTs (Fig. 6) have high mean or median fold-changes with one, GSTD3 showing consistently significant overexpression. Of these, GSTE2 has been shown to be involved in pyrethroid resistance40, whilst GSTE1, 2 and 5 have been implicated in DDT resistance48. Of the other phase two and three detoxification families, two UGTs (AGAP006222 and AGAP011564) and two carboxylesterases (COEAE6O and COEAE8O) are expressed with high mean or median expression or consistently over-expressed (Fig. 6).

Pyrethroid metabolising P450s with contrasting patterns of expression within species were also explored. For example, CYP6P3 is overexpressed in all but two An. coluzzii populations; the lab-selected resistant and a field population from Niger. Similarly, CYP6AA1 and CYP6M2 are largely overexpressed in An. coluzzii, excepting Niger, Nigeria. These data demonstrate that complete convergence of P450 overexpression cannot be expected along a continental scale.

Cuticular proteins

113 cuticular proteins were included in the full gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis; after filtering for lowly-expressed genes, only 61 of these remained. 20 of these genes showed a mean or median fold-change of above two in resistant populations, and although none showed significant over-expression in 19/28 experiments, nine showed upregulation in at least 16, including CPLCX3, CPR130, CPAP3-C, CPR16, CPR140, CPR59, CPR79, CPLCP12 and CPR81 (Supplementary Table 7).

Expression of neuronal-related genes

Gene-set enrichment analysis of GO terms on the 5% most down-regulated genes for median expression revealed significant enrichments in synapse (15 genes), sodium channel activity (10 genes) and chemical synaptic transmission (13 genes). The primary target site for pyrethroid insecticides, the Vgsc, is not present in the full gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis, but investigation of the secondary analyses shows sporadic down-regulation in An. coluzzii and An. funestus but not An. gambiae, suggesting that changes in expression of this gene are unlikely to be playing a role in resistance. Interestingly, Ace-1 expression demonstrated up-regulation in almost all An. coluzzii and An. gambiae populations whilst it is down-regulated in all 5 of the An. funestus populations. The gene coding for the beta-2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is significantly overexpressed in 11 out of 28 experiments.

Other a priori resistance candidates

A number of genes and gene families have recently been implicated in insecticide resistance, including CSPs, hexamerins, alpha-crystallin, the transcription factor Maf-S and d7 salivary proteins30,31,33,46. Of the eight chemosensory proteins, just three remained in the full gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis, CSP3, CSP4 and SAP1, none of which showed high mean or median fold-changes across four species. Similarly, three hexamerins were included in these data, all three of which showed high mean fold changes ranging from 2.64 to 3.4. Further exploration revealed that overexpression was observed in all An. arabiensis and the majority of An. gambiae experiments, with the orthologs of AGAP001345 and AGAP001657 being overexpressed in two (Uganda and FUMOZ) out of five An. funestus datasets. Just two a-crystallins were present in the data, neither of which showed an expression-association with resistance. The transcription factor Maf-S was previously identified as up-regulated across multiple An. gambiae s.l populations in the meta-analysis of microarray data31. It also shows similarly consistent overexpression in the RNA-Sequencing data, with 12 out of 28 populations exhibiting significant up-regulation.

Transcriptional regulation of insecticide resistance

Previous work using transcriptomic time-course data revealed putative transcription factors regulating the expression of transcripts post-pyrethroid exposure49. Here, we used the GENIE3 algorithm in the Grenadine package to re-capitulate a gene regulatory network utilising the 28 RNA-sequencing and including 31 microarray experiments. After filtering score for the top 5th percentile (Supplementary Data 3), 50,966 interactions were predicted. Firstly, we investigated Maf-S due to its prior link with insecticide resistance33. 269 putative interactions were identified, including the pyrethroid-resistance related transcripts CYP6M2, CYP6Z3, CYP9J4, two ABC transporters and three GSTs including GSTMS1. To validate the utility of this approach, microarray data published from a Maf-S knockdown33 was compared with the model predictions; 83 out of the predicted 269 genes were present on the list. We then carried out a permutation analysis, and out of 1000 permutations only 18 had 83 or more overlaps (p = 0.018) giving confidence to the model predictions.

To determine which transcription factors are likely to play a role in resistance, enrichment analysis was performed on the predicted interaction partners for each transcription factor: Rootletin was associated with genes significantly enriched for oxoreductase activity (p = 0.00943) and was linked with CYP6P3, CYP6P4 and CYP6P5, CYP6AA1, CYP6M2 and CYP6Z4; genes predicted to interact with Su(H) were similarly enriched in oxoreductase activity (p = 9.19e-3); Antp, Cbt and Sug were significantly enriched in cellular response to stress (p = 5.19e-4; 3.83e-4; 2.30e-8), Asciz and Org-1 to sensory response to chemical stimulus (p = 5.56e-4; 1.69e-4), E(spl)m3-HLH and Grh with structural constituent of the cuticle (p = 8.36e-5; 1.71e-2); exex with acetylcholine metabolic process (p = 3.57e-3); Grau, Scrt and Toy with G protein-coupled receptor activity (p = 1.47e-5; 1.01e-2; 2.46e-6); HLH3B with neurogenesis (p = 4.01e-2); Onecut with synpase organisation (p = 5.26e-3); Row with response to stress (p = 8.97e-6) and TFAM with electron transport chain (1.25e-7). A number of transcription factors were enriched in higher order functions, such as RNA metabolic processes, gene expression and aromatic compound metabolic processes.

Discussion

Despite the wide availability of transcriptomic data for major malaria vectors, no study to date has analysed these data across the four primary vectors, An. gambiae, An. coluzzii, An. arabiensis and An. funestus. In this study we performed a meta-analysis of these data, demonstrating clear convergence of molecular mechanisms of known insecticide resistance genes, as well as discovering novel candidates showing high levels of over-expression across the divergent species. We present a user-friendly python package, AnoExpress, which allows users to explore, visualise, and analyse the transcriptomic meta-analysis data.

Integrating differential expression and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data has the potential to enhance the discovery of novel resistance markers41,50. We integrated whole-genome sequence data from the Ag1000G with our transcriptomic meta-analysis, estimating signals of positive selection in wild mosquitoes, and locating the intersection of genes that both are highly overexpressed and are located at sites of selection signals. As over-expression of genes is a common mechanism which can confer insecticide resistance, cis-acting mutations which are likely to increase the expression of nearby genes are expected to be under positive selection. Indeed, cis-acting factors have been identified on a triple-mutant haplotype around CYP6AA1 in East African An. gambiae23, and in An. funestus driving the expression of CYP6P9a/b51.

The transcriptomic meta-analysis recovered many known resistance genes from metabolic gene families, including CYP6P3 (the CYP6P9a/b ortholog), CYP6P4, CYP6AA1, CYP9K1, CYP6Z2, CYP6Z3, CYP6M2 and Gste221,22,23. Each of these cytochrome P450s have been shown to directly metabolise insecticides22,52 as well as being associated with selective sweeps in field populations18,32. Additionally, several detoxification genes showing consistent overexpression have recently been implicated in gene duplication events in the An. gambiae complex, including CYP9K1, CYP6AA1, COEAE60 and GSTE2-423,53. The appearance of these genes in both candidates with consistently high mean/median fold change, as well as those consistently expressed over multiple datasets demonstrates the power of this approach. CYP4H17 is a striking example of a cytochrome P450 that has been overlooked for further validation and is a promising candidate for functional validation in both An. gambiae s.l and An. funestus. Examples of differing directionality of expression within species were also seen in within the cytochrome P450s known to actively metabolise pyrethroids, indicating that although the same gene families are often overexpressed across multiple populations, the same patterns shouldn’t be applied holistically to all populations across Africa.

In addition to detoxification genes, we see a signature of oxidative stress response. For example, Maf-S is involved in the Nrf2-cnc pathway, which induces expression of stress response genes upon changes to the oxidative stress levels of the cell33. Interestingly, Maf-S has been shown to have a role in pyrethroid resistance and was identified from consistent overexpression in microarray datasets33 and is similarly consistently overexpressed in the RNA-Sequencing data, whilst another member of the pathway, Keap1, is upregulated in An. funestus from Ghana. In addition to this characterised pathway, protein DJ-1 (AGAP000705) and Catalase are consistently overexpressed, both these genes play a role in protection against oxidative stress54. These data are consistent with previous publications indicating that insecticide exposure induces an oxidative stress response55,56.

Signatures of expression in candidates related to cuticular hydrocarbons were also present, which may indicate a change to lipid processing as recently proposed57,58 or be related to a thicker cuticle25. Genome-wide expression scans highlighted multiple gene clusters of cuticular protein families as outliers of gene expression, including the CLPCA, CPLCG, CPLCP and CPR families, which is reflected in the large number of these genes in the top candidate gene lists based on median and mean fold-changes. AGAP010368, an ortholog to a gene involved in fatty acid alpha-oxidation in Drosophila, a long chain fatty acid CoA ligase (AGAP009159) and a fatty acid elongase (AGAP003195) are consistently over expressed. The large number of cuticular proteins (20/113) highly expressed and the lack of those consistent across all populations may suggest high levels of redundancy.

We observe little differential expression of the major target site genes, such as the target of pyrethroids the Vgsc and dieldrin Rdl. As previously reported, the expression profile of the OP and carbamate target Ace-1 is an exception, often upregulated in An. coluzzii and An. gambiae yet showing negative fold-changes An. funestus experiments. It is worth noting that all five An. funestus experiments included in this study use the same susceptible comparator strain, FANG, and so this result could be a peculiarity of this laboratory strain. We find regular over-expression of the gene coding for the beta-2 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AGAP010057), recently associated with Pirimiphos-methyl resistance in a genome-wide association study12.

As well as physiological changes which directly confer resistance to insecticides, the potential for mosquitoes to avoid contact with insecticides and exploit humans when they are least protected is a serious threat to malaria vector control. Mosquito behaviour is likely to be driven in part by gene expression59 and transcriptomic studies may allow us to identify candidate genes involved in insecticide-resistant behaviours. This is of particular interest given the difficulty in measuring behavioural resistance in wild mosquito populations. Interestingly, enrichment analyses highlighted that our expression candidate genes were enriched for genes involved in olfactory processes. Gustatory receptor 49 (AGAP001169) shows a median fold-change of 3.39, the highest of any olfactory receptor in our data, and is a promising candidate for behaviourally-linked insecticide resistance. The odorant receptors 13 (AGAP009396) and 9 (AGAP008333) also show high median fold-changes of 2.73 and 2.71, respectively. It is, however, important to note that adaptation of susceptible strains to insectary rearing could cause the downregulation of olfactory genes, and so contribute to these signals.

We also identify candidate genes from gene families not previously associated with resistance in malaria vectors. The ortholog of neural lazarillo (AGAP009281) has a high median fold-change, a gene which is known to contribute to longevity, stress resistance and behavioural change through the JNK stress response pathway in Drosophila60. Several venom allergens also exhibit high median fold-changes. Interestingly, Venom allergen 5 has been associated with resistance in Culex through dsRNA and over-expression in cells61. These genes are poorly understood but a number have been found in the salivary gland proteome where they have a diverse range of functions, with none currently being characterised62.

Trans-acting regulation plays an important role in modulating gene expression to insecticide stress in insects33,63,64,65. To explore whether we could identify transcription factors involved in insecticide resistance, we inferred a gene regulatory network. The predicted interactors of several transcription factors were enriched in GO terms related to insecticide resistance. Amongst them is Rootletin, which is known to play a role in behavioural response in Drosophila66 and was previously linked to resistance as a key hub in response to insecticide exposure49, whilst Grau has been linked to pyrethroid resistance in Aedes populations67. Other transcription factors enriched in insecticide resistance-related terms that are consistent with known roles in Drosophila includes Cabut, which has been shown to regulate stress response68, E(spl)m3-HLH which is linked with stress granules69, Grh that is involved in cuticular repair70, Exex is involved in neuronal function71, Onecut with synapse organisation72 and Tfam is a mitochondrial transcription factor, with a role in oxidative stress response73.

We also explored the role that gene expression plays in shaping levels of genetic diversity across the genome. Protein evolution is constrained by purifying selection, which acts to prevent deleterious mutations from spreading in a population74. Previous studies have shown a relationship between higher gene expression and a slower accumulation of deleterious mutations50. We find a similar relationship in Anopheles mosquitoes, with the most highly expressed genes displaying lower rates of pN/pS, as well as a reduction in measures of genetic diversity, and replicate this effect across three mosquito species. Anopheles gambiae s.l populations exhibit extremely large effective population sizes, which should accelerate the removal of deleterious mutations. Between species differences support this, as An. arabiensis displays lower nucleotide diversity, but higher rates of pN/pS for the most highly expressed genes.

In this study, we present a holistic overview of signatures of gene expression in the major malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae s.l and Anopheles funestus. As well as establishing relationships between gene expression and whole-genome sequence data, we demonstrate the importance and convergence of detoxification genes, as well as highlighting putative transcription factors and novel gene families involved in insecticide resistance. Despite the power in this study there are several limitations that should be considered; Anopheles have a gene/loss factor five times that of Drosophila14 resulting in many gene families with one-to-many orthologs which have been excluded from this study, which results in a loss of data. In addition, the An. funestus data is from one experiment, and therefore is likely to have significant batch effects. Next, here we take ‘insecticide resistance’ as an overall phenotype because the populations grouped in this study have differential resistances to different classes, although all are pyrethroid resistant. Finally, we utilise read count files from published studies and compare within studies only to avoid extraneous confounding factors; however, this will lead to slight variations in expression data due to different methodologies used to extract the counts and precludes inter-study direct comparisons. Even after taking these limitations into count, these data highlight novel functional validation and genomic surveillance targets for malaria vector control in Africa.

Methods

RNA-sequencing data

All RNA-sequencing data published comparing resistant and susceptible members of An. gambiae, An. coluzzii, An. arabiensis and An. funestus were retrieved from Google Scholar in April 2022. Of the 28 resistant populations studied, 15 are An. coluzzii, 3 are An. gambiae, 5 are An. arabiensis and 5 are An. funestus (Supplementary Table 1)34,35,36,37,38,39,40. As multiple studies used the same susceptible populations due to the widespread resistance found in endemic settings, replicates of the same populations across studies were present (Supplementary Table 1). Count files were retrieved from authors of each paper and combined to form one large counts file. VectorBase was used to retrieve orthologs from each species to An. gambiae PEST and the counts of one-to-many relationships were averaged.

Differential expression analysis

The data was then normalised with DESeq2 v1.2675 using the estimateSizeFactors, estimateDispersions and the varianceStabilizingTransformation methods. Differential expression analysis (DEA) was performed with DESeq2 v1.26 in R v3.6.3. Due to batch effects and large differences in library depth between the included RNA-Sequencing studies, we only performed DEA within each experiment, comparing the susceptible (control) to the resistant strain (case). Positive fold changes indicate over-expression in the resistant strain. Hypothesis testing was performed with the DESeq2 wald test.

Microarray data

We integrated Microarray data from an earlier meta-analysis31 into AnoExpress. As this was performed at the transcript level rather than genes, we averaged log2 fold change and adjusted p-value data across transcripts for a given gene to match the AnoExpress meta-analysis.

Gene-set enrichment analysis

Gene set-enrichment was performed using the hypergeometric test implementation in SciPy, incorporated into AnoExpress. GO terms were extracted from VectorBase and PFAM domains from Grau-Bové et al. 76,77.

Genomic clustering

Using the gamb_colu_arab analysis we calculated and averaged the Pearson’s correlation between log2 fold changes for each neighbouring gene pair in the dataset, and then calculated the mean pearsons R across all pairs. We excluded An. funestus due to differences in synteny compared to An. gambiae s.l. To determine whether this value was higher than expected based on chance, we randomly permuted the positions of all genes in the genome 1000 times, calculated the Pearsons correlation between neighbouring genes, and calculated the mean. We considered the effect significant if the fraction of permutations showing a more extreme value than the actual true value was below 0.05.

Genetic diversity

Using log2 count data from the gamb_colu_arab analysis, we calculated the median counts across all samples, susceptible or resistant, and binned genes into 5% percentiles of expression level. We excluded An. funestus, as sufficient whole-genome sequence data is not yet publicly available. We selected three representative cohorts from across the geographic range of each species to analyse from the Anopheles 1000 genome project32; An. gambiae from Hauts-Bassins; Burkina Faso, Gbadolite; Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nagongera; Uganda, An. coluzzii from Hauts-Bassins; Burkina Faso, Tiassale; Cote D’Ivoire, and Turkana County, Kenya and An. arabiensis from Hauts-Bassins; Burkina Faso, Nagongera; Uganda, and Muleba; Tanzania, collected between 2012 and 2019. We randomly selected 50 individuals from each cohort. Using segregating sites only, we calculated the number of non-synonymous and synoynmous sites for each transcript, using the first transcript annotation for each gene, up to -RC. We calculated the overall CDS length per transcript and calculated the number of synonymous or non-synoynmous mutations per 1000 bp of CDS. We also calculated nucleotide diversity and Wattersons Theta across the entire length of the gene (including introns), using scikit-allel v1.2.178. Populations described in further detail23,79,80,81.

Genome-wide selection scan (GWSS) data

We integrate data from H12 genome-wide selection scans44 from the selection-atlas. More information on the GWSS and peak-calling algorithm can be found in Supplementary Text 2.

Genome-wide expression scans

We calculate a sliding window mean of log2 fold-change data, for the gamb_colu_arab_fun analysis, with a window size of 10 genes and a step of 2 genes.

Statistics and reproducibility

All code used for the paper is available on Github (https://github.com/sanjaynagi/AnoExpress) or as part of the Supplementary Text provided with the manuscript.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Results from the differential expression analyses are stored in the github repository for the AnoExpress python package - https://github.com/sanjaynagi/AnoExpress, and can be explored in the cloud with a series of Google Colaboratory notebooks, or on user’s local machines. Source data for the main figures in the manuscript is stored on figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28921100.v2).

All RNA-sequencing data is available from the publications listed in Supplementary Table 1. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study, are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

Code availability

All code used for this study is available on GitHub: https://github.com/sanjaynagi/AnoExpress or in the provided Supplementary Texts.

References

WHO. World Malaria Report (WHO, 2023).

Bhatt, S. et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211 (2015).

World Health Organization. WHA72 (World Health Organization, 2018).

Churcher, T. S., Lissenden, N., Griffin, J. T., Worrall, E. & Ranson, H. The impact of pyrethroid resistance on the efficacy and effectiveness of bednets for malaria control in Africa. Elife 5, e16090 (2016).

Cornelie, S. et al. Salivary gland proteome analysis reveals modulation of anopheline Unique Proteins in Insensitive acetylcholinesterase resistant Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 9, e103816 (2014).

Coetzee, M. et al. Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles amharicus, new members of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Zootaxa 3619, 246–274 (2013).

Sinka, M. E. et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. 3, 1–34 (2010).

Guo, D. et al. ACE: an efficient and sensitive tool to detect insecticide resistance-associated mutations in insect acetylcholinesterase from RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 330 (2017).

Scott, J. G. Life and death at the voltage-sensitive sodium channel: evolution in response to insecticide use. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 64, 243–257 (2019).

Nauen, R., Bass, C., Feyereisen, R. & Vontas, J. The role of cytochrome P450s in insect toxicology and resistance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 67, 105–124 (2022).

Clarkson, C. S. et al. The genetic architecture of target-site resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in the African malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Mol. Ecol. 30, 5303–5317 (2021).

Grau-Bové, X. et al. Resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in West African Anopheles is spreading via duplication and introgression of the Ace1 locus. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009253 (2021).

Small, S. T. et al. Radiation with reticulation marks the origin of a major malaria vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 31583–31590 (2020).

Neafsey, D. E. et al. Highly evolvable malaria vectors: the genomes of 16 Anopheles mosquitoes. Science 347, 1258522 (2015).

Hemingway, J. & Ranson, H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45, 371–391 (2000).

Ingham, V. A., Grigoraki, L. & Ranson, H. Pyrethroid resistance mechanisms in the major malaria vector species complex. Entomol. Gen. 43, 515–526 (2023).

Logan, R. A. E., Mäurer, J. B., Wapler, C. & Ingham, V. A. Uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) are associated with insecticide resistance in the major malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae s.l. and Anopheles funestus. Sci. Rep. 14, 19821 (2024).

Hearn, J. et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies a CYP9K1 haplotype conferring pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa. Mol. Ecol. 31, 3642–3657 (2022).

Irving, H., Riveron, J. M., Ibrahim, S., Lobo, N. F. & Wondji, C. S. Positional cloning of rp2 QTL associates the P450 genes CYP6Z1, CYP6Z3 and CYP6M7 with pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Heredity 109, 383–392 (2012).

Ibrahim, S. S., Ndula, M., Riveron, J. M., Irving, H. & Wondji, C. S. The P450 CYP 6Z1 confers carbamate/pyrethroid cross-resistance in a major African malaria vector beside a novel carbamate-insensitive N485I acetylcholinesterase-1 mutation. Mol. Ecol. 25, 3436–3452 (2016).

Vontas, J. et al. Rapid selection of a pyrethroid metabolic enzyme CYP9K1 by operational malaria control activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4619–4624 (2018).

Yunta, C. et al. Cross-resistance profiles of malaria mosquito P450s associated with pyrethroid resistance against WHO insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 161, 61–67 (2019).

Njoroge, H. et al. Identification of a rapidly-spreading triple mutant for high-level metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae provides a real-time molecular diagnostic for antimalarial intervention deployment. Mol. Ecol. 31, 4307–4318 (2022).

Ibrahim, S. S., Riveron, J. M., Stott, R., Irving, H. & Wondji, C. S. The cytochrome P450 CYP6P4 is responsible for the high pyrethroid resistance in knockdown resistance-free Anopheles arabiensis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 68, 23–32 (2016).

Balabanidou, V., Grigoraki, L. & Vontas, J. Insect cuticle: a critical determinant of insecticide resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 27, 68–74 (2018).

Balabanidou, V. et al. Cytochrome P450 associated with insecticide resistance catalyzes cuticular hydrocarbon production in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9268–9273 (2016).

Wood, O. R., Hanrahan, S., Coetzee, M., Koekemoer, L. L. & Brooke, B. D. Cuticle thickening associated with pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Parasites Vectors 3, 67 (2010).

Martinez-Torres, D. et al. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol. Biol. 7, 179–184 (1998).

Weill, M. et al. The unique mutation in ace-1 giving high insecticide resistance is easily detectable in mosquito vectors. Insect Mol. Biol. 13, 1–7 (2004).

Ingham, V. A. et al. A sensory appendage protein protects malaria vectors from pyrethroids. Nature 577, 376–380 (2019).

Ingham, V. A., Wagstaff, S. & Ranson, H. Transcriptomic meta-signatures identified in Anopheles gambiae populations reveal previously undetected insecticide resistance mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 9, 5282 (2018).

The Anopheles gambiae 1000 Genomes Consortium. Genetic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nature 552, 96 (2017).

Ingham, V. A., Pignatelli, P., Moore, J. D., Wagstaff, S. & Ranson, H. The transcription factor Maf-S regulates metabolic resistance to insecticides in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genom. 18, 669 (2017).

Williams, J. et al. Sympatric populations of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Southwest Burkina Faso evolve multiple diverse resistance mechanisms in response to intense selection pressure with pyrethroids. Insects 13, 247 (2022).

Simma, E. A. et al. Genome-wide gene expression profiling reveals that cuticle alterations and P450 detoxification are associated with deltamethrin and DDT resistance in Anopheles arabiensis populations from Ethiopia. Pest Manag. Sci. 75, 1808–1818 (2019).

Messenger, L. A. et al. A whole transcriptomic approach provides novel insights into the molecular basis of organophosphate and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Ethiopia. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 139, 103655 (2021).

Ingham, V. A. et al. Integration of whole genome sequencing and transcriptomics reveals a complex picture of the reestablishment of insecticide resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii. PLOS Genet. 17, e1009970 (2021).

Ibrahim, S. S. et al. Molecular drivers of insecticide resistance in the Sahelo-Sudanian populations of a major malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii. BMC Biol. 21, 125 (2023).

Wipf, N. C. et al. Multi-insecticide resistant malaria vectors in the field remain susceptible to malathion, despite the presence of Ace1 point mutations. PLOS Genet. 18, e1009963 (2022).

Kouamo, M. F. M. et al. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis and functional validation linked a cluster of epsilon glutathione S-transferases with insecticide resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Africa. Genes 12, 561 (2021).

Nagi, S. C., Oruni, A., Weetman, D. & Donnelly, M. J. RNA-Seq-Pop: exploiting the sequence in RNA sequencing—a Snakemake workflow reveals patterns of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 946–961 (2023).

Yang, T.-H., Yang, Y.-C. & Tu, K.-C. regCNN: identifying Drosophila genome-wide cis-regulatory modules via integrating the local patterns in epigenetic marks and transcription factor binding motifs. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 296–308 (2022).

Leffler, E. M. et al. Revisiting an old riddle: What determines genetic diversity levels within species?. PLOS Biol. 10, e1001388 (2012).

Garud, N. R., Messer, P. W., Buzbas, E. O. & Petrov, D. A. Recent selective sweeps in North American Drosophila melanogaster show signatures of soft sweeps. PLOS Genet. 11, e1005004 (2015).

Müller, P. et al. Field-caught permethrin-resistant Anopheles gambiae overexpress CYP6P3, a P450 that metabolises pyrethroids. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000286 (2008).

Isaacs, A. T., Mawejje, H. D., Tomlinson, S., Rigden, D. J. & Donnelly, M. J. Genome-wide transcriptional analyses in Anopheles mosquitoes reveal an unexpected association between salivary gland gene expression and insecticide resistance. BMC Genom. 19, 1–12 (2018).

Namiki, T. et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP307A1/Spook: a regulator for ecdysone synthesis in insects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 367–374 (2005).

Ortelli, F., Rossiter, L. C., Vontas, J., Ranson, H. & Hemingway, J. Heterologous expression of four glutathione transferase genes genetically linked to a major insecticide-resistance locus from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Biochem. J. 373, 957–963 (2003).

Ingham, V. A., Elg, S., Nagi, S. C. & Dondelinger, F. Capturing the transcription factor interactome in response to sub-lethal insecticide exposure. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 100018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cris.2021.100018(2021).

Duret, L. & Mouchiroud, D. Determinants of substitution rates in mammalian genes: expression pattern affects selection intensity but not mutation rate. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 68–070 (2000).

Leon, M. et al. Association of a rapidly selected 43.kb transposon-containing structural variation with a P450-based resistance to pyrethroids in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. PLoS Genetics 20, e1011344 (2024).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Assessing cross-resistance within the pyrethroids in terms of their interactions with key cytochrome P450 enzymes and resistance in vector populations. Parasites Vectors 14, 1–13 (2021).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals high complexity of copy number variation at insecticide resistance loci in malaria mosquitoes. Genome Res. 29, 1250–1261 (2019).

Lavara-Culebras, E. & Paricio, N. Drosophila DJ-1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress and show reduced lifespan and motor deficits. Gene 400, 158–165 (2007).

Champion, C. J. & Xu, J. Redox state affects fecundity and insecticide susceptibility in Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Rep. 8, 13054 (2018).

Otali, D. et al. Increased production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and reduced adult life span in an insecticide-resistant strain of Anopheles gambiae. Bull. Entomol. Res. 104, 323–333 (2014).

Adams, K. L. et al. Selection for insecticide resistance can promote Plasmodium falciparum infection in Anopheles. PLOS Pathog. 19, e1011448 (2023).

Adams, K. L. et al. Cuticular hydrocarbons are associated with mating success and insecticide resistance in malaria vectors. Commun. Biol. 4, 911 (2021).

Govella, N. J., Johnson, P. C. D., Killeen, G. F. & Ferguson, H. M. Heritability of biting time behaviours in the major African malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis. Malar. J. 22, 238 (2023).

Ruiz, M., Wicker-Thomas, C., Sanchez, D. & Ganfornina, M. D. Grasshopper Lazarillo, a GPI-anchored Lipocalin, increases Drosophila longevity and stress resistance, and functionally replaces its secreted homolog NLaz. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 776–789 (2012).

Lv, Y. et al. Venom allergen 5 is associated with deltamethrin resistance in Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 52, 672–682 (2015).

Arcà, B., Lombardo, F., Struchiner, C. J. & Ribeiro, J. M. C. Anopheline salivary protein genes and gene families: an evolutionary overview after the whole genome sequence of sixteen Anopheles species. BMC Genom. 18, 153 (2017).

Gao, L., Qiao, H., Wei, P., Moussian, B. & Wang, Y. Xenobiotic responses in insects. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 109, e21869 (2022).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Mapping a Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) conferring pyrethroid resistance in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. BMC Genom. 8, 34 (2007).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Cis-regulatory CYP6P9b P450 variants associated with loss of insecticide-treated bed net efficacy against Anopheles funestus. Nat. Commun. 10, 4652 (2019).

Styczynska-Soczka, K. & Jarman, A. P. The Drosophila homologue of Rootletin is required for mechanosensory function and ciliary rootlet formation in chordotonal sensory neurons. Cilia 4, 9 (2015).

Campbell, C. L. et al. Vgsc-interacting proteins are genetically associated with pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti. PLoS ONE 14, e0211497 (2019).

Mukherjee, S., Paricio, N. & Sokol, N. S. A stress-responsive miRNA regulates BMP signaling to maintain tissue homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022583118 (2021).

Singh, A. et al. The transcriptional response to oxidative stress is independent of stress-granule formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 33, ar25 (2022).

Mace, K. A., Pearson, J. C. & McGinnis, W. An epidermal barrier wound repair pathway in Drosophila is mediated by grainy head. Science 308, 381–385 (2005).

Joanne, P. O., Scott, H. & Chris, Q. D. DrosophilaHB9 is expressed in a subset of motoneurons and interneurons, where it regulates gene expression and axon pathfinding. J. Neurosci. 22, 9143 (2002).

Nguyen, D. N. T., Rohrbaugh, M. & Lai, Z.-C. The Drosophila homolog of Onecut homeodomain proteins is a neural-specific transcriptional activator with a potential role in regulating neural differentiation. Mech. Dev. 97, 57–72 (2000).

Matsuda, T., Kanki, T., Tanimura, T., Kang, D. & Matsuura, E. T. Effects of overexpression of mitochondrial transcription factor A on lifespan and oxidative stress response in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 430, 717–721 (2013).

Emiliano, T. et al. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv, 2023.2008.2008.552445. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445 (2023).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21 (2014).

Giraldo-Calderón, G. I. et al. VectorBase: an updated bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vectors and other organisms related with human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D707–D713 (2015).

Grau-Bové, X. et al. Evolution of the insecticide target Rdl in African Anopheles is driven by interspecific and interkaryotypic introgression. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 2900–2917 (2020).

Alistair Miles. ‘cggh/scikit-allel: v1.3.9’. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13467522 (2024).

Kientega, M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of major malaria vectors reveals the evolution of new insecticide resistance variants in a longitudinal study in Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 23, 280 (2024).

Kamau, L. et al. The Anopheles coluzzii range extends into Kenya: detection, insecticide resistance profiles and population genetic structure in relation to conspecific populations in West and Central Africa. Malar. J. 23, 122 (2024).

Dennis, T. P. W. et al. Cryptic population structure and insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae from the southern Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci. Rep. 14, 21782 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Deutsches Zentrum für Infektionsforschung grant (TTU 03.705) to VAI. SCN was funded by an MRC CASE studentship (MR/R015678/1) and a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant (NIAID R01-AI116811 to Martin Donnelly and David Weetman). The authors would like to thank all those who freely gave count data from prior publications, including Louisa Messenger, Dieunel Derilus, Pie Müller, Nadja Wipf, Charles Wondji, Sulaiman Ibrahim, Jack Hearn, Thomas van Leeuwen and Wannes Dermauw. We also thank Hilary Ranson, David Weetman and Alistair Miles for feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, analysis, paper drafting (VAI); Conceptualisation, analysis, creation of python package, paper drafting (SCN).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Dieunel Derilus and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Dr Wannes Dermauw and Dr Christina Karlsson Rosenthal. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagi, S.C., Ingham, V.A. A multi-omic meta-analysis reveals novel mechanisms of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors. Commun Biol 8, 790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08221-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08221-6