Abstract

A digital health intervention (DHI) using SMS precision nudging to drive RSV vaccine uptake among adults over 60 was launched with a large community pharmacy chain in 2023, two months after the vaccine’s FDA approval for adult administration in the United States. Tens of thousands of patients texted back. In this exploratory investigation, we employed thematic analysis and structural topic modelling to extract topics (e.g., Kind declines, Moral disgust, etc.), sentiment (negative to positive), and function (emotional to practical) expressed in the text replies in order to understand patient attitudes and behavioural determinants of RSV vaccination. The analyses reveal 10 topics from the thematic analysis and 30 more granular topics from the structural topic modelling. Expressed attitudes shifted over the course of the DHI, with less negativity later in the intervention. People who did not receive the flu vaccine and people with commercial insurance responded more frequently that they would not get vaccinated. Specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were associated with overall replies and specific topics. Framing intervention messages with information about emotional consequences elicited the highest proportion of replies; framing with anticipated regret elicited the lowest proportion. We extend previous work by leveraging unsolicited replies to analyse public attitudes toward a new vaccine, with implications for future RSV and other vaccine interventions at pharmacies and elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Successful uptake of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) vaccine added to the U.S. vaccination schedule for older adults in 2023 (Jones, Jenkins, Adam Williams et al., 2024; Venkatesan, 2023) had a significant positive public health impact (Molnar, La, Verelst et al., 2024). Understanding determinants of RSV vaccination behaviour, which were unknown when the vaccine was introduced, is critical to drive continued uptake for eligible adults. In this paper, we present findings from a precision nudging digital health intervention (DHI) targeting RSV vaccination among U.S. adults aged 60+ launched with a large community pharmacy chain in September 2023. We undertook an exploratory analysis of unsolicited patient responses to the intervention nudges to better understand any attitudes toward RSV vaccination expressed by adults over 60. In particular, we examined topical themes of replies, and how those varied according to the intervention content received, time (early or late in the intervention), and available demographic factors. This novel data set provides insight to patient perceptions of a new vaccine promoted within a pharmacy setting and may foster understanding how to more effectively drive RSV vaccination.

The nature of the determinants of RSV vaccination was particularly uncertain given at least three new influences on attitudes toward new vaccines and indications following the COVID-19 pandemic. First, mRNA vaccines authorised for COVID-19 vaccination aroused concerns for some people that COVID-19 vaccines appeared rushed to market (Wilson, Goswami, Baqui et al., 2023). Consumers may overgeneralise their attitudes toward mRNA vaccines to the prefusion F protein-based RSV vaccines by Pfizer and GSK approved by the FDA for use in 2023 (Krause, Beets, Howell et al., 2023) or extend them to the mRNA vaccine for RSV introduced in 2024 (Levien, Baker, 2025).

Second, COVID-19 introduced novel behavioural determinants for new vaccines. While there are temporal and cross-vaccine variations in vaccine acceptance(Larson, Jarrett, Eckersberger et al., 2014), the universe of vaccination barriers was complicated by COVID-19. For example, COVID-19 vaccination was subject to barriers rooted in conspiracy theories and political beliefs (Blazek, West, Bucher, 2023; Bolsen, Palm, 2022). In contrast, people report generally more positive perceptions of flu vaccines than COVID-19 vaccines (SteelFisher et al., 2023). There was an open question whether the new RSV vaccine would share the negative political associations of the COVID-19 vaccine or the less controversial associations of the flu vaccine. Early evidence suggests RSV vaccination is less polarising than COVID-19. While both intention to vaccinate against RSV and actual uptake of the RSV vaccine lagged flu and COVID-19 vaccination in the US in 2023 (Black, Kriss, Razzaghi et al., 2023), low perceptions of risk from and little knowledge about RSV may have presented the primary barriers to vaccination (Haeder, 2024; La, Bunniran, Garbinsky et al., 2024).

Third, the people and institutions well-positioned to provide credible vaccine information shifted during the pandemic. There was public loss of trust in institutions like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Pitts, Poland, 2023), with perceptions that their recommendations reflect politics rather than science (SteelFisher et al., 2023). While provider recommendations continue to drive uptake of health behaviours (Keyworth, Epton, Goldthorpe et al., 2020), patient access to providers is limited by capacity (Porter, Boyd, Skandari et al., 2023) and it is not possible to administer vaccines via the telehealth visits that extend provider capacity (Cortez, Mansour, Qato et al., 2021). It was therefore unclear which credible sources, if any, might promote RSV vaccination to eligible patients after its approval.

One likely option is pharmacists. As accessible community-based healthcare providers, pharmacists have filled a gap in healthcare systems, which was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most Americans live within a few miles of a pharmacy (Wittenauer, Shah, Bacci et al., 2024). Since state regulatory changes permitted the administration of vaccines by pharmacists, vaccination rates increased (Burson, Buttenheim, Armstrong et al., 2016) particularly for older adults (Newlon, Kadakia, Reed et al., 2020) with flu vaccination rates 24% higher in patients who received pharmacy-based interventions (Murray, Bieniek, del Aguila et al., 2021), and over 57% higher for pneumococcal vaccines in older adults (Sheer, Nau, Dorich et al., 2021). Pharmacist-administered vaccines are often provided sooner and at lower cost than physician-administered ones (Crunenberg, Hody, Ethgen et al., 2023). Pharmacies’ extended hours compared to provider offices accounts for some of their reach (Carroll, Herbert, Nguyen et al., 2024), with over 30% of vaccinations provided by one pharmacy chain outside of clinic hours (Goad, Taitel, Fensterheim et al., 2013). More than 90% of Americans say they trust pharmacists, who offer an accessible option for vaccination, to dispense medications and fill prescriptions, provide counsel on medication interactions, and administer vaccinations (McHugh et al. (2022)). The trust and credibility that pharmacists earn as a result of their community embeddedness translates to improved health equity (Carroll et al., 2024), with people of colour and older populations visiting their local pharmacies more often and using them for basic health services more frequently than white and younger Americans (CVS Health, 2024).

The intervention under study sent text message nudges on behalf of a community pharmacy chain to promote RSV vaccination among eligible adults. People who replied to these text messages would reasonably believe they were communicating with the pharmacy and/or pharmacist. Their replies, therefore, may provide information about their attitudes and decision-making process when it comes to the new vaccine and its administration. Capturing popular attitudes can be achieved through various methods including self-report survey and social media surveillance, each of which has drawbacks. Demand characteristics and cognitive biases may influence self-report research findings on barriers to vaccination (Graupensperger, Abdallah, Lee, 2021; Lang, Benham, Atabati et al., 2021; Romer, Jamieson, 2020). Consequently, studies using self-report methods might overlook unconventional barriers to vaccination, underestimate the prevalence of socially stigmatised barriers, such as belief in conspiracy theories or distrust of medical authorities (Blazek et al., 2023; Smallpage, Enders, Drochon et al., 2023), and overestimate vaccination rates (Wolter, Mayerl, Andersen et al., 2022). Social media posts are subject to similar flaws where posters knowingly craft messages with an eye toward audience engagement (Lindström, Bellander, Schultner et al., 2021), which is greater for posts with negative affect (Berger, Milkman, 2012) and out-group animosity (Rathje, Van Bavel, van der Linden, 2021), with faster spread of provocative information (Alipour, Galeazzi, Sangiorgio et al., 2024). While analysis of such posts can provide insight to vaccination attitudes (Cascini, Pantovic, Al-Ajlouni et al., 2022; Wang, Fan, Palacios et al., 2022), they also capture extreme polarisation that exaggerates private sentiment. On the other hand, sentiments expressed by pharmacy consumers directly and privately to the pharmacy in response to vaccination outreach, while not without bias, offer a different lens on vaccination determinants as well as feedback on intervention outreach that can be used to better drive vaccine uptake. Particularly in combination with other datasets and research approaches, consumer text message replies may help improve vaccine promotion.

The use of text message to deliver a behavioural intervention for older adults also merits scrutiny. While text message interventions are increasingly common, there has been some research suggesting older people may struggle with replying to such interventions in recognised formats (Gwynne, Ratwani, Dixit, 2023). Moreover, older adults may prefer different types of text message content compared to other age groups (Kuerbis, van Stolk-Cooke, Muench, 2017). Given that RSV vaccination is one of several vaccines specifically approved for older adults, their responses to a text message DHI for vaccination could provide insight into the suitability of that outreach channel for vaccine promotion.

This study builds on qualitative methods used elsewhere to understand unsolicited responses to a text message intervention driving COVID-19 vaccination (Blazek et al., 2023). Qualitative analysis is suitable when phenomena are not well understood or when the goal is to better understand subjective experience (Kim, Sefcik, Bradway, 2017), both of which apply to the RSV vaccination experience in the time frame studied. Qualitative research also plays a crucial role in the development and implementation of public health interventions by providing researchers with a nuanced understanding of attitudes, perceptions, and contextual factors, which are essential for strategic planning and successful execution of effective and socially accepted health interventions (Hamilton, Finley, 2019). Exploring unsolicited text replies provides a unique opportunity to comprehend people’s thoughts and attitudes about vaccinations beyond formal research settings. This approach may also shed light on populations, such as older adults, who have been underrepresented in vaccine attitude research (Chen, Wang, Yi et al., 2023). Limited data available on intervention recipients, including past flu vaccination at the pharmacy chain, type of health insurance, and whether they lived in a rural or urban area, also allows examination of whether these factors are related to differences in expressed vaccine attitudes. And because the texts were sent in reply to intervention outreach, there is an opportunity to look at differences in responses elicited by different content types. Given the research aims to understand determinants of RSV vaccination, thematic analysis (Blazek et al., 2023) was used in combination with structural topic modelling (Roberts, Stewart, Tingley et al., 2014) to extract and organise topics from the text replies.

Materials and methods

Transparency and openness

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brian, Lawrence, Kaiser et al., 1984). The study was approved by Solutions IRB (HHS #IRB00008523) with a waiver of informed consent. Data were anonymised.

Study design

The DHI consists of three best-in-class control messages and 19 behaviourally designed treatment messages (see Supplemental Table 2), each of the latter crafted to incorporate specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs; Carey, Connell, Johnston et al., 2019; Johnston, Carey, Connell Bohlen et al., 2021; Michie, Richardson, Johnston et al., 2013) chosen to address determinants of vaccination behaviour. The DHI operates on principles of behavioural reinforcement learning (BRL; (Mnih, Kavukcuoglu, Silver et al., 2015; Sutton, Precup, Singh, 1999), which after an initial randomly selected message analyses recipient demographics, medical history, and engagement data (such as clicking a link in a text message) to optimise subsequent message content for maximising the likelihood of individuals receiving an RSV vaccine. The DHI for RSV vaccination studied here was developed using the COM-B framework which asserts that behaviours are more likely to occur when people have the capability, opportunity, and motivation to perform them (Michie, van Stralen, West, 2011); each included BCT was selected due to evidence that it address these categories of determinants and can promote behaviours (Ford, West, Bucher et al., 2022). The DHI’s development process, based on behavioural design, has been previously detailed (Bucher, Blazek, West, 2022; Ford et al., 2022) and has been applied to driving vaccine appointments (Blazek, West, Bucher, 2023). A comprehensive breakdown of behavioural determinants, categorised as Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (Michie et al., 2011), along with a detailed list of BCTs categorised according to the BCTv1 taxonomy, can be found in Supplemental Table 1, and the full text of both Treatment and Control messages in Supplemental Table 2.

Participants and settings

The eligible population was drawn from a large community pharmacy chain. Individuals included in the study were aged 60 years and older at the time of the intervention, had not yet received an RSV vaccine per pharmacy vaccine records, had filled a prescription within the last 6 months, and were subscribed to pharmacy messaging services. During the study period, a total of 2,481,987 individuals were included in the text message intervention, receiving a maximum of 9 messages each. Approximately 25% of all recipients were randomised into the control condition (626,004 people) and 75% into the treatment condition (1,555,864 people). These allocations reflect the use of a control condition to assess the use of the intervention as a quality control initiative for the pharmacy and not a research initiative per se. The study sample included all responders from September 17, 2023, to January 31, 2024. Limited demographic data was available regarding the population, except age (as required to determine eligibility for the RSV vaccine) and the covariate data described in the data collection section.

Data collection

The data used in this study emerged unexpectedly as an outcome of the intervention, comprising spontaneous text replies from individuals who took part in the intervention. Notably, participants were not formally provided with the option to respond freely. Patient actions were explicitly guided, including a CTA to book an appointment, opting to “STOP,” or requesting “HELP.” In total, 35,716 people replied to the intervention content generating 105,848 replies. Recognised text message replies such as “STOP” and “HELP” were removed from the dataset using a SQL script. After this data cleaning, 46,964 replies remained. Covariate data were provided as part of the consumer profile from the pharmacy: flu vaccination history (record of a flu vaccine in the last 24 months), insurance type (commercial versus non-commercial), and rural versus urban indicator (derived by geocoding the patient’s address and determining if the coordinates fall within an urban geometric area). These data elements were provided as they influenced aspects of the intervention outreach, e.g., whether consumers were eligible for outreach, insurance coverage of vaccination, and which pharmacy location they were directed to).

Thematic analysis

To ensure a comprehensive exploration of both the depth and breadth within our dataset, we implemented a dual analytical approach to qualitative analysis. Initially, a random subset of the data underwent manual coding by two qualitatively trained researchers with domain knowledge related to vaccination behaviour. We employed thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun, Clarke, 2006) with elements from grounded theory (Strauss, Corbin, 1997), specifically theoretical sensitivity (Glaser, 1978). The thematic analysis sample consisted of 2952 codes applied to 2757 replies received from 2132 people.

Structural topic modelling

Machine-facilitated structural topic modelling was applied to the entire dataset, including the manually coded replies. An automated method was chosen given the size of the dataset; the manually derived topics allowed the research team to interpret and assess the structural topic modelling results.

Text replies preprocessing

Text replies were cleaned using ‘textclean’ (Rinker, 2018a) and ‘lexicon’ (Rinker, 2018b) R packages. First, raw text was checked using ‘check_text()’ to reveal patterns that are problematic for textual analysis, such as special text including emoticons, emojis, URLs, non-ASCII characters, contractions, dates, timestamps, email addresses, hashtags, html formatted text, incomplete sentence end marks, handle tags, and slang terms. Special text was replaced with text suitable for analysis or removed as part of the data cleaning process. For example, emojis and emoticons were replaced with their associated text hash (see Rinker (2018a) for more details). Similarly, common slang was converted to corresponding meanings (see Rinker 2018a). Next, all non-alphanumeric characters were removed, and text was converted to lower case. Replies were then converted into token units using ‘quanteda’ (Benoit, Watanabe, Wang et al., 2018). Tokens were stemmed to the root word (Towler, Bondaronek, Papakonstantinou et al., 2023) and a custom set of stop words were removed. Specifically, a widely used stop words list (snowball, available at https://snowballstem.org/) was customised based on thematic sensitivity (e.g., keeping verbs like “should,” words related to intent like “will,” and temporal descriptives like “after,” and removing common non-informative date words like “Monday”).

Model estimation

We employed a structural topic model to quantitatively discover distinct topics, determine their prevalence, and estimate their relationship with our covariates of interest (Roberts et al., 2014). First, we estimated a confirmatory model to corroborate the 10 thematic analysis topics; the results (available upon request) are not reported on here because they did not produce a coherent set of topics as judged by the trained research team. Therefore, we next examined an exploratory number of topics. A k-search procedure ranging from 5 to 40 topics was conducted to determine the optimal number of topics, focusing on the trade-off between exclusivity and semantic coherence (see Supplemental Fig. 1). Four qualitatively trained researchers collaborated on naming, describing, and organising topics using a Machine Assisted Topic Analysis (Towler et al., 2023) approach. Word prevalence, uniqueness, and distinctiveness were examined, and a mapping procedure took place between thematic analysis topics and topics defined by the structural topic model. Contrasts were conducted to estimate the effect of key covariates on topic prevalence including treatment versus control messages, first versus last messages, flu vaccination status, health insurance type, and urban versus rural location.

Results

Thematic analysis identified 10 topics in the subset of text messages (see Table 1). Most frequent were Actions, Auto-replies, etc. (25.85%), Will not get vaccinated (20.49%), and Stop (17.82%). The structural topic model identified 30 topics in the full set of text messages (see Table 1). Most frequent were Pleading no with a side of adverse event (8.05%), RSV vs. flu FAQ (7.10%), and Corporate replies (6.50%). Each message could be coded to multiple categories; hence, prevalence by topic sums to more than 100%.

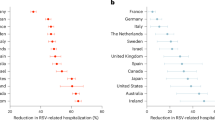

The topic mapping was made possible by the research team’s thematic sensitivity acquired by hand coding the subset of text messages. It was noted that messages often had an emotional tenor and varied in terms of their implied purpose, for example expressing an opinion or belief (“emotional”) to facilitating pharmacy transactions (“practical”). We therefore used axial coding (Mezmir, 2020) to organise the 30 exploratory topics in a two-dimensional space with axes corresponding to valence (negative to positive; Thelwall, Buckley, Paltoglou, 2011) and intent (emotional to practical; Gaspar, Pedro, Panagiotopoulos et al., 2016), see Fig. 1. We situated our consideration of emotional valence by categorising affective replies in terms of whether people were sending purely emotional replies (likely venting) or sending practical replies with either questions or informative statements. The structural topic model provided sentiment nuance, seen for example in the three Stop topics: Complex quits, Kind declines, and Frustrated farewells, that required human naming and interpretation. The structural topic model also produced many nonsense topics that differentiated on valence (e.g., Distrustful nonsense), emojis (e.g., Emoji potpourri), and foreign language (e.g., Non-English responses), as well as meaningful replies that were clearly not intended as replies to the DHI but rather communications intended for the pharmacy chain on other topics (e.g., Food).

Shape and colour indicate the mapping of structural topic model topics onto the 10 thematic analysis topics. Black star = Wrong recipient, teal circle = Help, red cross = Stop, purple plus = Already vaccinated, brown square = Will not get vaccinated, yellow triangle = Benign, and grey diamond = Nonsense. Size indicates topic proportions. Topics 1–10 are largest, topics 11–20 are of middle size, and topics 21–30 are smallest.

Many people responded with emojis. A summary of the specific emojis sent is presented as an emoji cloud in Fig. 2.

Relationships between behaviour change techniques and reply topics

Given our primary objective of delving into subjective experiences and extracting insights from a previously unexplored phenomenon (Kim et al., 2017), thematic analysis took precedence. Summarising the thematic analysis subset of messages, we found that reply topics differed by the BCT encoded in the outbound content, as shown in Table 2. Messages with the BCTs Reduce negative emotions (see Fig. 3 for example), Verbal persuasion about capability, and Information about emotional consequences elicited the most replies. These three BCTs leverage emotional responses to encourage a target behaviour and are likely relevant to pharmacy patients because their existing pharmacy relationship signals a health event, often negative such as a health condition requiring medication. Messages with the BCTs Anticipated regret, Social support (practical), and Comparative imagining of future outcomes elicited the fewest replies.

Relationships between condition and time and reply topics

Among the thematic analysis subset of messages, we explored relationships between condition and time and topics. Reply topic differed by condition (19 behaviourally designed and BCT encoded Treatment messages versus three best-in-class Control messages) and by time (the initial message, “First” versus the most recent message around week 20, “Last”), see Supplemental Table 3. More Help replies were sent by those in the Control condition (z = −4.35, p < 0.000). There were no other differences by condition. In reply to the First message there were more Help (z = 5.08, p < 0.000), more Stop (z = 2.81, p = 0.005), fewer Already vaccinated (z = −2.74, p = 0.006), more Will not get vaccinated (z = 6.93, p < 0.000), and fewer Actions, auto-replies, etc. (z = −9.93, p < 0.000) replies.

To further explore these relationships, we conducted a set of contrasts for Help and Will not get vaccinated topics from the structural topic model to test their relationship with condition and time. For condition, 13.87% of replies came from participants who received Control messages and 86.12% replies came from participants who received Treatment messages. Among the five Help topics, people in the Treatment group were more likely to send RSV vs. flu FAQ replies (t = 3.68, p < 0.001), see Fig. 4. There were no other associations among Help topics. For Will not get vaccinated topics, there was a marginal relationship between replies sent from participants in the Control group and likelihood of an Of God and Country reply (t = −1.75, p = 0.080). No other relationships between Will not get vaccinated topics and Treatment and Control groups were found.

For time, 25.11% of replies were to the First message and 19.38% were to the Last message. 55.51% of replies were neither first nor last and thus were excluded from this examination. For Help related topics, replies to the First message were more likely to be related to An RSV what? (t = −3.32, p < 0.001), Vaccine vagaries (t = −2.50, p = 0.012), and Hints of hesitation (t = −3.40, p < 0.001) topics. Replies to the Last message were more likely to be related to RSV vs. flu FAQ replies (t = 3.53, p < 0.001). Help me out replies were not associated with time. Within Will not get vaccinated topics, Of God and Country (t = −5.96, p < 0.001), Distrust of pharma (t = −2.97, p = 0.002), I don’t want [something] (t = −5.36, p < 0.001), Moral disgust (t = −4.26, p < 0.001), and Hard no (t = −2.41, p = 0.016) replies were all more likely to be sent to the First message. There was a marginal relationship to replies associated with the COVID-19 related topic and replies to the First message (t = −1.76, p = 0.078). Pleading no with a side of adverse events was not associated with either First or Last message.

Relationships between covariates and topics in structural topic model results

Reply topic also differed by demographics (flu vaccination obtained, health insurance type, and urban versus rural location), explored both with the thematic analysis (available upon request) and structural topic modelling topics, reported here. We explored Help and Will not get vaccinated; these reply topics offer the best opportunity to identify how we might increase vaccine uptake, either by addressing questions and concerns, or by better understanding and designing for patient-expressed barriers.

72.82% of replies came from participants who had no record of a flu vaccine in the last 24 months whereas 27.18% did. Among the five Help topics, people with no record of flu vaccines sent more An RSV what? (t = −3.29, p < 0.001) and Hints of hesitation (t = −6.26, p < 0.001) replies, and marginally more Vaccine vagaries replies (t = −1.69, p = 0.091). People who received the flu vaccine were more likely to send more RSV vs. flu FAQ reply (t = 10.15, p < 0.001). There was no impact of flu vaccination on Help me out. Among the seven Will not get vaccinated topics, people with no record of flu vaccines sent more I don’t want [something] (t = −9.46, p < 0.001), Moral disgust (t = −9.72, p < 0.001), Of God and Country (t = −8.23, p < 0.001), and Distrust of pharma (t = −4.88, p < 0.001) replies. People with a flu vaccine on record sent more COVID-19 related replies (t = 2.19, p = 0.029). There was no impact of flu vaccination on Pleading no with a side of adverse event and Hard no.

33.22% of replies came from participants who have commercial health insurance whereas 66.78% came from those who have non-commercial health insurance. Among the four Help topics, people with commercial health insurance sent more Vaccine vagaries (t = −2.20, p = 0.028) and Hints of hesitation (t = −4.56, p < 0.001) replies. People with non-commercial health insurance were more likely to send RSV vs. flu FAQ replies (t = 7.48, p < 0.001). There was no impact of type of insurance on An RSV what? and Help me out. Among the seven Will not get vaccinated topics, people with commercial health insurance sent more I don’t want [something] (t = −5.29, p < 0.001), Moral disgust (t = −5.20, p < 0.001), Of God and Country (t = −7.15, p < 0.001), and Distrust of pharma (t = −3.09, p = 0.002) replies. People with non-commercial health insurance sent more Pleading no with a side of adverse event (t = 2.21, p = 0.027) replies. There was no impact of type of insurance on COVID-19 related and Hard no.

20.74% of replies came from participants who were rural dwellers whereas 79.26% of replies came from participants who were urban dwellers. Among the five Help topics and the seven Will not get vaccinated topics, there was no impact of urban versus rural location. See Fig. 5.

Discussion

In this study, we identified topics from unsolicited text message replies to an RSV vaccination DHI implemented by a large community pharmacy chain shortly after the approval of the RSV vaccine in the United States. By performing both thematic analysis and structural topic modelling, we identified varied and nuanced topics that represent reactions to the RSV vaccine and to the DHI, as well as questions and concerns intended for the large community pharmacy chain that deployed the RSV vaccination DHI. We found that message topics shifted from September 2023 to February 2024, likely following increased awareness generally of the recently approved RSV vaccines and dropout of people with more negative attitudes from the intervention. People who did not receive the flu vaccine and people with commercial insurance responded more frequently that they would not get vaccinated. Content encoded with the BCT Information about emotional consequences elicited the highest proportion of replies, while the BCT Anticipated regret elicited the lowest proportion of replies.

Reply themes and extension of previous work on public attitudes toward vaccination

Our findings extend previous work on people’s attitudes toward and determinants of vaccination through the use of unsolicited in-the-moment feedback, and by examining attitudes toward a newly approved vaccine. In the “post”-COVID-19 period, new vaccines, especially those developed with mRNA technology, will likely face extra scrutiny by the general population. We saw fewer replies denoting unwillingness to get vaccinated over the course of the DHI as general awareness of the RSV vaccine presumably grew, a finding that is echoed by surveys of seniors’ future intent to vaccinate against RSV (Haeder, 2024). Also of interest, relatively few replies indicated lack of trust in public institutions, suggesting the political atmosphere around the introduction of the RSV vaccine was not as polarising as COVID-19. Distrust and political convictions do influence vaccination behaviour (SteelFisher et al., (2023) and may be countered by policy changes or community-based interventions like those directly administered by pharmacists. It will be worth continuing to monitor the influence of politics and trust in public institutions on vaccination behaviours as policies shift in the United States.

The unique dataset of unsolicited text message replies from DHI outreach recipients also extends the ability to triangulate on vaccination attitudes and perceptions. Social media sentiment analysis and content mining have been used extensively to understand public sentiment about vaccination (e.g., (Liew, Lee, 2021; Nuzhath, Tasnim, Sanjwal et al., 2020; Verma, Moudgil, Goel et al., 2023). Despite the performative aspects of social media, research has shown acceptable alignment between publicly expressed sentiment and self-reported attitudes on surveys (Chen, Chen, Pang et al., 2022). It is reasonable that people’s replies to text messages coming from their pharmacy about RSV vaccination bear a relationship to their actual attitudes, especially given the private and spontaneous nature of the replies.

Most reply topics identified by structural topic modelling were more practical than emotional. Many recipients requested information about RSV itself or the new vaccine and its administration. The frequency of these responses confirms prior research suggesting lack of familiarity as a barrier to RSV vaccination (La et al., 2024), while the waning frequency of these replies over time suggests knowledge became a less prominent barrier with the passage of time from the introduction of RSV vaccination to the U.S. market. Replies indicating that the recipient had already been vaccinated were also relatively frequent (6.12%) and increased from the first week of the study period to the last as people had an opportunity to vaccinate. Also common were messages conveying a future intention to become vaccinated (3.62%). Notably, the majority of vaccine refusals were also on the less emotional side of the continuum, suggesting that people’s reasons for declining RSV vaccination may not be as politically or conspiracy-theory tinged as those reported for COVID-19 vaccination (Blazek et al., 2023). Among the negatively valanced replies, Frustrated farewells were prominent and conveyed a reaction to the DHI rather than the target behaviour of RSV vaccination. While some replies do suggest a spillover effect of negative perceptions from COVID-19 vaccination (Wilson et al., 2023), these were relatively few (2.23%). The results suggest perceptions of RSV vaccines may have a less extreme negative tail than perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines.

The changing nature of reply topics over time underscores the importance of listening to people in their own words to fully understand how expressed attitudes about behaviours of key public health importance, such as vaccination, evolve as the behaviours become more familiar. More replies were sent in the Help, Stop, and Will not get vaccinated topics to the First message compared to the Last message, and in the Already vaccinated and Actions topics in reply to the Last message. Several negative subcategories of the Will not get vaccinated message type were also more common replies to the first message than the last. While waning negativity can be partially explained by uninterested recipients opting out of the intervention, shifts in information seeking and vaccination intentions suggest many people were learning about the new vaccine category and determining their intentions over the intervention period.

These findings align with key psychological theories about attitude change such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and the transtheoretical model. The ELM suggests that increased positivity of attitudes toward the RSV vaccine over time could be explained by repeated exposure to vaccine information via traditional and social media and in conversations with providers (Petty, Briñol, 2011); this pattern emerges from our results as replies indicating unwillingness to get vaccinated waned over the course of the study while replies indicating that the vaccine had already been received waxed over the course of the study. Similarly, the high number of Help replies sent early in the DHI may suggest people in the contemplation or preparation stages of change who are gathering information to help with a decision (Noar, 2017). The higher proportion of earlier replies seeking to unsubscribe is also consistent with general findings that people are more likely to unsubscribe from a text message campaign in the first few weeks (Cole-Lewis, Augustson, Sanders et al., 2017). A cross-sectional approach to understanding barriers to vaccination would not capture these time-based differences in patient attitudes.

Reply content by time may influence design decisions for future vaccination outreach. Assuming at least some of the people who sent negative replies to the intervention outreach subsequently successfully unsubscribed, those who remained subscribed may have become more open to vaccination over the duration of the intervention. This suggests that future messaging interventions may consider framing early and late outreach differently given a wider range of vaccine attitudes in the initial recipient group. To the extent a pharmacy patient’s general orientation toward vaccination is known (e.g., whether they have sent negative replies to prior outreach or have been vaccinated in previous years) and attitudes are influenced by the social and informational environment, it also may make sense to postpone outreach to those with known barriers to vaccination until later in the season when vaccination has been more normalised.

Reactions to operationalised behaviour change techniques

The importance of framing is also evident in our research. How content driving RSV vaccine uptake is presented can affect reactions and engagement, as demonstrated by different reply topic prevalence in response to different BCTs. For example, the BCT Information about emotional consequences, which emphasises positive outcomes of RSV vaccination such as peace of mind, elicits relatively many Help and Will not get vaccinated replies whereas the BCT Anticipated regret, which emphasises the negative consequences of failing to vaccinate, elicits relatively few of these replies. Given that most Help replies suggest at least some willingness to consider vaccination, in contrast to Will not get vaccinated replies, the ability of the same BCTs to elicit both hints at the complexity of framing. Indeed, prior research has found that both positive and negative frames can provoke reactance depending on factors such as the type of behaviour being encouraged, the level of freedom threat perceived by recipients, and the number of messages sent (Ratcliff, Jensen, Scherr et al., 2019; Shen, 2015).

The DHI used in this work personalises the selection of BCT after the first, randomly selected message, meaning there is an interaction between BCTs sent and the characteristics of the recipients, particularly their engagement or lack thereof with prior messages. While this limits the ability to interpret the impact of any BCT in isolation on reply content, it may help explain the reduction in negative replies over the course of the intervention. There are also patterns in which BCTs elicit which responses that are noteworthy despite the personalisation confound. For example, the BCT of Anticipated regret elicited the lowest proportion of replies overall and for Help replies, and was among the lowest elicitors of Will not get vaccinated replies. This BCT, which has been found to prompt a range of health behaviours including vaccination (Brewer, DeFrank, Gilkey, 2016), reminds people of potential negative consequences of (in)action and could be interpreted as inflammatory. The fact that it provoked relatively few responses in this intervention may mean it was well operationalized, or that people already understand the impact of their vaccination decisions on future health events and therefore do not find this BCT surprising.

Conversely, the BCTs Information about emotional consequences and Reduce negative emotions were associated with higher proportions of replies. In contrast to Anticipated regret, which focuses on missing celebrations if the unvaccinated person falls ill with RSV, the other two BCTs point to experiencing peace of mind and/or fear related to vaccination. It is possible that projecting emotions or mindset is less palatable to intervention recipients than a narrative event. Indeed, some people specifically replied that they did not agree with the characterisation of their emotions in the BCT. Future research could examine whether and how projecting recipient emotional responses via BCTs can effectively promote vaccination behaviour.

These text replies add nuance to the understanding of behavioural determinants of RSV vaccination alongside learnings from self-report surveys and social media analysis. Regardless of whether the reply was positive or negative, interacting with the DHI demonstrates engagement on the part of the patient, which creates opportunity for ultimate behavioural conversion (Cole-Lewis, Ezeanochie, Turgiss, 2019) and suggests an opportunity to design appropriate follow-up based on reply content. As previously noted, community pharmacy teams have earned significant patient trust (Carroll et al., 2024; Shen, Tan, 2022). It is clear many of the people who sent text replies believed that someone at the large community pharmacy chain would receive them. The ability to elicit detailed reactions from consumers about behaviours of public health importance that can enhance behavioural interventions offers another rationale beyond their direct impact for pharmacy-based vaccination services (Burson et al., 2016).

Demographic covariates and reply topics

Each of the three available covariates (flu vaccine indicator, insurance type, and rural/urban dwelling) was related to differences in reply topics. Additionally, in comparison with similar research using a more age-diverse population, older adults demonstrate differences in text message behaviour.

Impact of past flu vaccination

Prior flu vaccination was associated with reply frequency and topic, and patients’ likelihood of receiving an RSV vaccine. Those without a recent flu vaccination record indicator were represented to a greater extent in the Will not get vaccinated topics, and especially the topics indicative of deeper-rooted vaccine hesitancy such as Moral disgust, Of God and Country, and Distrust of pharma, suggesting an overall lower willingness to consider RSV vaccination. Among those who received the RSV vaccine, 77.97% had also received the flu vaccine at the pharmacy chain in prior years; among those who did not receive the RSV vaccine, 82.97% had not received the flu vaccine (see Supplemental Table 4). The flu vaccination indicator from the pharmacy has its own limitations. A negative indicator does not necessarily mean a person has not received a flu vaccine, as the pharmacy data does not capture flu vaccinations administered via competitor pharmacies or physician offices. However, a positive indicator does confirm prior flu vaccination. The pattern of response content among people with confirmed prior flu vaccination suggests that flu vaccination, a familiar and relatively non-controversial public health focus area (SteelFisher et al., 2023), might serve as a keystone behaviour to encourage RSV vaccination among the eligible population, particularly in pharmacy settings where both are available. Presence of a prior flu vaccination indicator in the patient record also may suggest more openness to new vaccines and guide the approach to vaccination outreach accordingly. Nudging multiple vaccinations simultaneously, particularly for those with prior flu vaccination behaviour on record, may be a fruitful avenue for increasing uptake of novel vaccines.

Impact of insurance type

Reply topics also differed by patients’ type of health insurance. People with commercial health insurance were more likely to send some types of Help replies and Will not get vaccinated replies compared to people with non-commercial health insurance such as Medicaid, Medicare, or Tricare. This pattern may partially speak to efforts by non-commercial health plans to educate their members about preventive vaccines, thereby increasing the likelihood the person has already formed a positive opinion about the vaccine. Given that eligibility for some non-commercial health plans is income-based, it is also possible that members of those plans are more mindful about the expense of sending text messages and therefore less likely to reply at all.

Cost may be a barrier to RSV vaccination depending on insurance plan. For those on Medicare coverage, RSV vaccination falls under Part D rather than Part B like the flu and COVID-19 vaccines and may not be fully covered (Hughes (2023); Wroblewski, Brust-Sisti, Bridgeman et al., 2024). Medicare enrolees without Part D coverage may be left completely out of pocket for the cost of RSV vaccination. RSV vaccination is not consistently covered by commercial plans (Wang, 2024), such that people with commercial coverage may also hesitate to vaccinate for cost reasons. Additional data elements such as household income (Li, Yu, Seabury et al., 2022). could be used in future research to better understand the impact of insurance type on vaccination attitudes. Additionally, future vaccination campaigns may consider insurance status and financial security as determinants to address, particularly in targeting the non-commercially insured who may be more vulnerable to cost concerns.

Impact of rural versus urban location

Replies from people living in rural areas included fewer Help and more Will not get vaccinated replies compared to those living in urban areas in the hand-coded subsample (see Supplemental Table 5). It is possible people in less densely populated areas perceive themselves less at risk from communicable diseases such as RSV due to fewer transmission opportunities. It is also possible that people in urban settings have more frequent contact with their pharmacy teams, given that an acceptable pharmacy radius is defined as 0.5 to 1 mile for urban settings but 10 miles for rural (Wittenauer et al., 2024). It is also possible that people in rural settings had more Will not get vaccinated intentions because it is less convenient for them to go to a pharmacy for vaccination. Outreach in rural areas may be important for future vaccination interventions given this pattern, and to the extent that geographical convenience is a factor, pharmacies may consider use of mobile vaccination units or scheduled vaccination events.

In the full set of replies, there were no differences in urban versus rural dwelling on replies within the four Help topics or within the seven Will not get vaccinated topics. We intend to explore this discrepancy in future research.

Use of text messaging for older adults

The most frequent reply topic, at almost 26% of total replies received, was Actions, auto-replies, etc. These replies include adding reactions such as thumbs up to a received message, pre-programmed responses indicating inability to answer, and nonsense strings of words and emojis. In comparison, a similar analysis of replies to a COVID-19 vaccination intervention for people aged 18 and over showed approximately 10% of replies were categorised this way (Blazek et al., 2023). The large number of non-meaningful replies aligns with research showing older adults have more difficulty replying to intervention text messages in recognised formats (Gwynne et al., 2023). However, it is notable that relatively few replies express direct negativity toward the intervention texts themselves. This may be because the intervention content and personalised delivery align with older adult preferences for messages that are personally relevant and aligned to their motivations (Zhang, Dieciuc, Dilanchian et al., 2024). Future text message DHI development for this age group might focus on user experience improvements that reduce confusion and facilitate understanding of functionality, given the low cost and high reach of text messaging as an intervention channel.

Benefit of using thematic analysis complemented by structural topic modelling

The dual analytic approach speaks to the benefits of employing statistical modelling with qualitative thematic analysis (Gaspar et al., 2016). This approach allows expert level coding to pair with machine generated topics, reducing the labour involved in manually coding tens of thousands of replies (Blazek et al., 2023), while additionally adding different levels of sensitivity to the analysis. On the one hand, the 30 topics identified via exploratory model estimation were not given sentiment scores, and topic summaries were, at face value, difficult to interpret (e.g., the topic Already vaccinated (location) was identified by highest-probability words rsv, last, unstop, thumbsup, p, st, booster). On the other hand, human-expert generated topics were limited in scope of replies reviewed and thus could not be sensitive to the variability present in the full set of replies. The thematic sensitivity acquired through manually coding replies enabled the researchers to find nuanced meaning in the structural topic modelling. Further clustering topics into thematic categories and comparison with topic intercorrelations allowed for insight into conceptual and ultimately practitioner relevant information that was not immediately apparent from either approach in isolation. The manually generated Help topic, for example, was further broken down into categories such as RSV vs. flu FAQ and Hints of hesitation, each with unique implications for barriers to address in future interventions. The axial coding of the structural topic modelling topics addresses a key limitation in social media research in general, which tends to focus more on the dimensions of valence (positive, negative, neutral, ambivalent) and less on the underlying functions or goals that affective expressions may serve (Gaspar et al., 2016).

Implications for future RSV and other vaccination interventions at pharmacies and elsewhere

The findings from our study have implications for how RSV vaccination DHIs are designed and implemented outside of the U.S., and for how future novel vaccine DHIs are designed and implemented within the U.S. This will be important as the RSV vaccine is approved in other countries, as new vaccines are introduced in the United States, and as people age into eligibility for vaccines. Designing interventions to support uptake of novel health behaviours is challenging without a robust existing evidence base; insights from consumers can help bridge the gap between introduction of the behaviour and publication of formal research insights on its determinants (including people’s attitudes toward it). Monitoring unsolicited feedback from intervention recipients in real time can present opportunities to quickly address barriers to vaccination or adjust messaging. It can also inform community pharmacy approaches to vaccination immediately by surfacing common questions and concerns expressed by consumers (Blazek et al., 2023; Golos, Guntuku, Piltch-Loeb et al., 2023) that are addressable via the pharmacy website, signage, pharmacist interaction, or other avenue. Given their value in driving increased vaccine uptake and eliciting consumer feedback that supports vaccine uptake, it is also worth exploring how to continue improving community pharmacies’ engagement with vaccination efforts.

The content of the Help replies sent by intervention recipients offers an immediate opportunity to improve this and other DHIs. Commonly asked questions, such as whether RSV can be co-administered with other vaccines and whether it is typically covered by insurance, could be addressed proactively in the initial outreach or reactively with either scripted replies or by linking to a Frequently Asked Questions resource. For example, the DHI used in this work was enhanced following the 2023 RSV vaccination effort to send relevant auto-replies to some of the most frequently occurring help topics in order to quickly connect patients with relevant information and resources.

Limitations

While we have highlighted benefits of using unsolicited responses to understand attitudes and vaccination determinants, there are limitations as well. Due to lack of data availability, we did not explore the following demographics known to be determinants of vaccination: gender, education, household income, political affiliation, and living in a county with higher 2020 Trump support (Sun, Monnat, 2022). Additionally, the large community pharmacy chain relied on own vaccination records only without querying state registries, meaning patients could have been vaccinated at another location such as a provider office or competitor pharmacy. Lack of complete vaccination records likely impacted reply topics such as Already vaccinated (location), Already vaccinated (time), and RSV vs. flu FAQ.

The dataset of text replies was large and messy, with many nonsense replies, typos and misspellings, autocorrections, auto-replies, and other quality issues (e.g. a bug in the ‘textclean‘ package (Rinker (2018a) that converted “EXP” to “excuse me tongue sticking out.”). Text messages are also shorter than typical texts analysed with structural topic modelling (in this dataset, the median length was just 3 words), which leaves less room for the sender to establish context that aids modelling and interpretation. Additionally, topic modelling is not sensitive to ironic use, sarcasm, or metaphors, in both text, emoji, and emoticon use. Working with such a dataset requires significant cleaning and the exercise of human judgment to determine which messages hold meaning. These challenges, which are less common in internet research, stem from how smartphone use changes user-generated content (Melumad, Inman, Pham, 2019).

The unsolicited nature of the text message replies means the texts likely do not accurately represent the breadth of sentiment in the intervention population, as the majority of DHI recipients did not reply. Relatively few people actually replied (1.64%), and a quarter of those replies were actions, auto-replies, etc. or nonsense (25.9% in thematic analysis; 26.9% in structural topic modelling). The text replies we received tended to be more emotionally weighted; assuming a range of attitudes in the population, this suggests that people with more neutral reactions to the message refrained from replying. These data may therefore capture both positive and negative extremes more than they exist in the general population.

Finally, the BRL-driven selection of message BCTs based on which are most likely to convert the recipient to vaccination, while a strength of the intervention, introduces limitations to the ability to interpret the relationship between BCTs and replies. The selection of BCTs by the BRL might have influenced the number and reply topic we observed to each BCT. Moreover, because BCTs were not randomly sent, there is necessarily an interaction between recipient characteristics and the BCTs they received subsequent to their first message. Future research could focus solely on replies to randomly selected BCTs (i.e., first message) or use a non-personalised experimental setup to directly assess reactions to different BCTs.

Future directions

Given possible expansion of the population eligible for RSV vaccination and a continued focus on vaccinating vulnerable populations like older and pregnant people and infants against RSV, a critical future direction is to codify our understanding of the determinants of RSV vaccination, including consumer perceptions and attitudes, in support of public health interventions. The data used in the current research offers additional opportunities for analysis to answer critical questions about what behavioural determinants are experienced by whom and under what conditions. A limitation of the current work is limited availability of additional demographic data to understand patterns in responses to vaccination outreach. Future research efforts will incorporate such data to enable insights on the relationship between additional demographics such as age and gender, and social determinants of health such as income and educational attainment and engagement, as in the current study, as well as behavioural outcomes.

The RSV vaccine ushers in an expanded adult immunisation schedule to protect against the “tripledemic” consisting of RSV, flu, and COVID-19. With the addition of COVID-19 boosters, RSV, and potentially other vaccinations, it will also be important to understand perceptions of concurrent vaccination, which has primarily been studied in the context of paediatric and travel-related vaccines (Bonanni, Steffen, Schelling et al., 2023; Kaaijk, Kleijne, Knol et al., 2014; Wallace, Ryman, Privor-Dumm et al., 2022). The topic identified in this study, RSV vs. flu FAQ, speaks to the need for further research on public opinion toward different vaccines like RSV, flu, and COVID-19 as well as opinion on the co-administration of two or more at a time. The unsolicited replies analysed here provide context for the development of subsequent interventions targeting the administration of multiple vaccines (COVID-19, flu, and RSV) in a single visit. This study also provides context for future operational efficiencies from the large community pharmacy chain (e.g., if someone texts the octagonal stop sign emoji, they might receive a pre-scripted reply asking, “would you like to opt out of future notifications?”).

Pharmacy teams are well-positioned to provide continued access to important services like vaccination, particularly in medically underserved areas and populations. Pharmacists enjoy the trust of the communities they serve, have direct access to consumers to support clinical decision making, and can administer and influence the flu vaccination that may serve as a keystone behaviour for other recommended vaccinations. Their potential role in positively influencing vaccine uptake supports legislative efforts to expand pharmacist scope in the United States to provide vaccinations and related counselling (Davis, Dedon, Hoffman et al., 2023; Newlon et al., 2020). There is also a complementary opportunity to develop future DHIs that leverage the role of the pharmacist and pharmacies to promote vaccinations.

Finally, future research will help to disentangle the influence of nudge content on behavioural outcomes and reply types. The DHI used in the current research is designed to personalise the selection of BCT for each recipient based on their interaction history. Future iterations may account for the content of text replies alongside more objective data such as message clicks and vaccination administration to better understand the specific effects of different nudge types. Such inquiry could also add understanding to the complexity of framing effects. We found the same BCTs elicited Help and Will not get vaccinated replies, which indicate different levels of willingness to consider vaccination and suggest opportunities to explore which BCTs are best suited to prompt vaccination and how to best operationalise BCTs to produce intended effects. Future research can tease apart which individual characteristics may be associated with different replies to the same BCTs. The resultant improved understanding of characteristics that lead different people to respond differently to those BCTs will help with faster, more effective intervention tactic selection for future vaccination DHIs and other applications of framing.

Conclusion

Understanding vaccination determinants, including attitudes and perceptions, directly influences the content of DHIs designed to support vaccine uptake. When a novel vaccine such as RSV is first introduced, direct commentary from eligible patients provides a valuable source of insight into perceptions of the vaccine and potential behavioural determinants. This research examined a unique dataset of unsolicited text message replies to a DHI for RSV vaccination administered through a national community pharmacy chain. A combination of behavioural expert topic analysis of a subset of messages and machine-assisted structural topic modelling enabled identification of ten major themes in the replies, with subthemes organised along two axes of emotional valence and intent. These themes included declarations of unwillingness to get vaccinated against RSV, requests for help and information, and information about vaccines already received, each of which provides actionable insights to pharmacy teams and can be used to refine the DHI. By recognising the diverse replies and engagement by different people, stakeholders, including behavioural designers, researchers, policymakers, pharmacists, and the healthcare industry, can better anticipate and respond to reactions and concerns to DHIs for vaccination to ultimately support vaccine uptake.

Data availability

We did not seek permission to share data due to prevalent personal health information (PHI). The dataset analysed for this study is therefore not publicly available. R code with edits to Machine Assisted Topic Analysis (MATA; Towler et al., 2023) to accommodate text message reply data is available upon request.

References

Alipour S, Galeazzi A, Sangiorgio E et al. (2024) Cross-platform social dynamics: an analysis of ChatGPT and COVID-19 vaccine conversations. Sci Rep 14(1):2789. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53124-x

Benoit K, Watanabe K, Wang H et al. (2018) Quanteda: an r package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. J Open Source Softw 3(30):774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

Berger J, Milkman KL (2012) What makes online content viral? J Mark Res 49(2):192–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353

Black CL, Kriss JL, Razzaghi H et al. (2023) Influenza, updated COVID-19, and respiratory syncytial virus vaccination coverage among adults — United States, fall 2023. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 72:1377–1382. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7251a4

Blazek ES, West AB, Bucher A (2023) Responses to a COVID-19 vaccination intervention: qualitative analysis of 17k unsolicited sms replies. Health Psychol 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001297

Bolsen T, Palm R (2022) Politicization and COVID-19 vaccine resistance in the u.S. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 188(1):81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2021.10.002

Bonanni P, Steffen R, Schelling J et al. (2023) Vaccine co-administration in adults: an effective way to improve vaccination coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother 19(1):2195786. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2195786

Boyatzis RE (1998) Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage, New York, NY

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Brewer NT, DeFrank JT, Gilkey MB (2016) Anticipated regret and health behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 35(11):1264–1275. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000294

Bucher A, Blazek ES, West AB (2022) Feasibility of a reinforcement learning–enabled digital health intervention to promote mammograms: retrospective, single-arm, observational study. JMIR Formative Res 6(11):e42343

Burson RC, Buttenheim AM, Armstrong A et al. (2016) Community pharmacies as sites of adult vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother 12(12):3146–3159. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1215393

Carey RN, Connell LE, Johnston M et al. (2019) Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Ann Behav Med 53(8):693–707

Carroll JC, Herbert SMC, Nguyen TQ et al. (2024) Vaccination equity and the role of community pharmacy in the United States: a qualitative study. Vaccine 42(3):564–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.12.063

Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni YA et al. (2022) Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of the literature. eClinicalMedicine 48:101454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101454

Chen N, Chen X, Pang J, Borga LG, D’Ambrosio C, Vögele C. (2022) Measuring COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Consistency of Social Media with Surveys. In: Hopfgartner F, Jaidka K, Mayr P, Jose J, Breitsohl J (eds). Social Informatics. Cham: Springer International Publishing, p 196–210

Chen Y, Wang J, Yi M et al. (2023) The COVID-19 vaccination decision-making preferences of elderly people: a discrete choice experiment. Sci Rep 13(1):5242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32471-1

Cole-Lewis H, Augustson E, Sanders A et al. (2017) Analysing user-reported data for enhancement of smokefreetxt: a national text message smoking cessation intervention. Tob Control 26(6):683–689. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052945

Cole-Lewis H, Ezeanochie N, Turgiss J (2019) Understanding health behavior technology engagement: pathway to measuring digital behavior change interventions. JMIR Formative Res 3(4):e14052. https://doi.org/10.2196/14052

Cortez C, Mansour O, Qato DM et al. (2021) Changes in short-term, long-term, and preventive care delivery in us office-based and telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum 2(7):e211529–e211529. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1529

Crunenberg R, Hody P, Ethgen O et al. (2023) Public health interest of vaccination through community pharmacies: a literature review. J Adv Pharm Res 7(2):77–86. https://doi.org/10.21608/aprh.2023.189159.1210

CVS Health (2024) The Rx report: The future of community pharmacy opens doors to healthier communities. https://www.cvshealth.com/content/dam/enterprise/cvs-enterprise/pdfs/2024/CVS%20Health%20RX%20Report%202023.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2024

Davis M, Dedon L, Hoffman S et al. (2023) Emergency powers and the pandemic: reflecting on state legislative reforms and the future of public health response. J Emerg Manag 21(7 (Spec Issue: Research and Applied Science: COVID-19 Pandemic Response)):19–35. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.0772

Ford KL, West AB, Bucher A et al. (2022) Personalized digital health communications to increase COVID-19 vaccination in underserved populations: a double diamond approach to behavioral design. Front Digital Health 4 https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.831093

Gaspar R, Pedro C, Panagiotopoulos P et al. (2016) Beyond positive or negative: qualitative sentiment analysis of social media reactions to unexpected stressful events. Comput Hum Behav 56:179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.040

Glaser BG (1978) Theoretical sensitivity. University of California, Oakland, CA

Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE et al. (2013) Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Ann Fam Med 11(5):429. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1542

Golos AM, Guntuku SC, Piltch-Loeb R et al. (2023) Dear pandemic: a topic modeling analysis of COVID-19 information needs among readers of an online science communication campaign. PLoS ONE 18(3):e0281773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281773

Graupensperger S, Abdallah DA, Lee CM (2021) Social norms and vaccine uptake: College students’ COVID vaccination intentions, attitudes, and estimated peer norms and comparisons with influenza vaccine. Vaccine 39(15):2060–2067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.018

Gwynne K, Ratwani R, Dixit R (2023) Technology issues experienced by older populations responding to COVID-19 vaccine text outreach messages. JAMIA Open 6(3): https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooad066

Haeder SF (2024) US seniors’ intention to vaccinate against RSV in fall and winter 2023–2024. Health Affairs Scholar 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/haschl/qxae003

Hamilton AB, Finley EP (2019) Qualitative methods in implementation research: an introduction. Psychiatry Res 280:112516

Hughes RH, IV (2023) CMS can fix Medicare vaccine coverage to protect seniors from RSV. Health Affairs Forefront, https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20230328.539974

Johnston M, Carey RN, Connell Bohlen LE et al. (2021) Development of an online tool for linking behavior change techniques and mechanisms of action based on triangulation of findings from literature synthesis and expert consensus. Transl Behav Med 11(5):1049–1065

Jones CH, Jenkins MP, Adam Williams B et al. (2024) Exploring the future adult vaccine landscape—crowded schedules and new dynamics. npj Vaccines 9(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00809-z

Kaaijk P, Kleijne DE, Knol MJ et al. (2014) Parents’ attitude toward multiple vaccinations at a single visit with alternative delivery methods. Hum Vaccin Immunother 10(8):2483–2489. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.29361

Keyworth C, Epton T, Goldthorpe J et al. (2020) Delivering opportunistic behavior change interventions: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Prev Sci 21(3):319–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01087-6

Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C (2017) Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health 40(1):23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21768

Krause NM, Beets B, Howell EL et al. (2023) Collateral damage from debunking mRNA vaccine misinformation. Vaccine 41(4):922–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.045

Kuerbis A, van Stolk-Cooke K, Muench F (2017) An exploratory study of mobile messaging preferences by age: middle-aged and older adults compared to younger adults. J Rehabil Assist Technol Eng 4 https://doi.org/10.1177/2055668317733257

La EM, Bunniran S, Garbinsky D et al. (2024) Respiratory syncytial virus knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions among adults in the United States. Human Vaccines Immunother 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2303796

Lang R, Benham JL, Atabati O et al. (2021) Attitudes, behaviours and barriers to public health measures for COVID-19: a survey to inform public health messaging. BMC Public Health 21(1):765. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10790-0

Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E et al. (2014) Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 32(19):2150–2159

Levien TL, Baker DE (2025) Respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (mRNA). Hosp Pharm 60(2):105–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/00185787241298140

Li K, Yu T, Seabury SA et al. (2022) Trends and disparities in the utilization of influenza vaccines among commercially insured US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 40(19):2696–2704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.058

Liew TM, Lee CS (2021) Examining the utility of social media in COVID-19 vaccination: unsupervised learning of 672,133 twitter posts. JMIR Public Health Surveill 7(11):e29789. https://doi.org/10.2196/29789

Lindström B, Bellander M, Schultner DT et al. (2021) A computational reward learning account of social media engagement. Nat Commun 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19607-x

McHugh J, Elul B, Narayan S (2022) The prescription of trust – pharmacists transforming patient care. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/file/3632/download?token=12_k8iia

Melumad S, Inman JJ, Pham MT (2019) Selectively emotional: how smartphone use changes user-generated content. J Mark Res 56(2):259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718815429

Mezmir EA (2020) Qualitative data analysis: an overview of data reduction, data display, and interpretation. Res humanities Soc Sci 10(21):15–27

Michie S, van Stralen M, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 6(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M et al. (2013) The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 46(1):81–95

Mnih V, Kavukcuoglu K, Silver D et al. (2015) Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518:529–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14236

Molnar D, La EM, Verelst F et al. (2024) Public health impact of the adjuvanted rsvpref3 vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus prevention among older adults in the United States. Infect Dis Ther https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-00939-w

Murray E, Bieniek K, del Aguila M et al. (2021) Impact of pharmacy intervention on influenza vaccination acceptance: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm 43(5):1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01250-1

Newlon JL, Kadakia NN, Reed JB et al. (2020) Pharmacists’ impact on older adults’ access to vaccines in the United States. Vaccine 38(11):2456–2465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.061

Noar SM (2017) Transtheoretical model and stages of change in health and risk messaging. Oxford Res Encyclopedia Commun https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.324

Nuzhath T, Tasnim S, Sanjwal RK et al. (2020) COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy, misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media: a content analysis of twitter data

O’Brian CA, Lawrence DS, Kaiser ET et al. (1984) Protein kinase c phosphorylates the synthetic peptide arg-arg-lys-ala-ser-gly-pro-pro-val in the presence of phospholipid plus either ca2+ or a phorbol ester tumor promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 124(1):296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291x(84)90951-3

Petty RE, Briñol P (2011) The elaboration likelihood model. Handb Ther Soc Psychol 1:224–245

Pitts PJ, Poland GA (2023) Trust and science: Public health’s home field advantage in addressing vaccine hesitancy and improving immunization rates. Vaccine 41(38):5483–5485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.08.003

Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR et al. (2023) Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med 38(1):147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07707-x

Ratcliff CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL et al. (2019) Loss/gain framing, dose, and reactance: a message experiment. Risk Anal 39(12):2640–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13379

Rathje S, Van Bavel JJ, van der Linden S (2021) Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(26):e2024292118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024292118

Rinker, T (2018a) Textclean: Text cleaning tools. https://github.com/trinker/textclean

Rinker, T (2018b) Lexicon: Lexicon data. https://github.com/trinker/lexicon

Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Tingley D et al. (2014) Structural topic models for open‐ended survey responses. Am J Polit Sci 58(4):1064–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12103

Romer D, Jamieson KH (2020) Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc Sci Med 263:113356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356

Sheer RL, Nau DP, Dorich N et al. (2021) Medicare Advantage–pharmacy partnership improves influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates. Am J Manag Care 27(10):425–431

Shen AK, Tan ASL (2022) Trust, influence, and community: why pharmacists and pharmacies are central for addressing vaccine hesitancy. J Am Pharm Assoc 62(1):305–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.10.001

Shen L (2015) Antecedents to psychological reactance: the impact of threat, message frame, and choice. Health Commun 30(10):975–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.910882

Smallpage SM, Enders AM, Drochon H et al. (2023) The impact of social desirability bias on conspiracy belief measurement across cultures. Political Sci Res Methods 11(3):555–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.1

SteelFisher GK, Findling MG, Caporello HL et al. (2023) Trust in US federal, state, and local public health agencies during COVID-19: Responses and policy implications. Health Aff 42(3):328–337. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01204

SteelFisher GK, Findling MG, Caporello HL et al. (2023) Divergent attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine vs influenza vaccine. JAMA Netw Open 6(12):e2349881–e2349881. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49881

Strauss A, Corbin JM (1997) Grounded theory in practice. Sage, New York, NY

Sun Y, Monnat SM (2022) Rural‐urban and within‐rural differences in COVID‐19 vaccination rates. J Rural Health 38(4):916–922

Sutton RS, Precup D, Singh S (1999) Between mdps and semi-mdps: a framework for temporal abstraction in reinforcement learning. Artif Intell 112(1):181–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-3702(99)00052-1

Thelwall M, Buckley K, Paltoglou G (2011) Sentiment in Twitter events. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 62(2):406–418

Towler L, Bondaronek P, Papakonstantinou T et al. (2023) Applying machine-learning to rapidly analyze large qualitative text datasets to inform the COVID-19 pandemic response: comparing human and machine-assisted topic analysis techniques. Front Public Health 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1268223

Venkatesan P (2023) First rsv vaccine approvals. Lancet Microbe 4(8):e577. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-5247(23)00195-7

Verma M, Moudgil N, Goel G et al. (2023) People’s perceptions on covid-19 vaccination: an analysis of twitter discourse from four countries. Sci Rep 13(1):14281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41478-7

Wallace AS, Ryman TK, Privor-Dumm L et al. (2022) Leaving no one behind: defining and implementing an integrated life course approach to vaccination across the next decade as part of the immunization agenda 2030. Vaccine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.039

Wang J, Fan Y, Palacios J et al. (2022) Global evidence of expressed sentiment alterations during the covid-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 6(3):349–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01312-y

Wang TY (2024) Rsv vaccination—the juice is worth the squeeze. JAMA Intern Med 184(6):611–611. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0219

Wilson E, Goswami J, Baqui AH et al. (2023) Efficacy and safety of an mrna-based rsv pref vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 389(24):2233–2244. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307079

Wittenauer R, Shah PD, Bacci JL et al. (2024) Locations and characteristics of pharmacy deserts in the United States: a geospatial study. Health Affairs Scholar, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/haschl/qxae035

Wolter F, Mayerl J, Andersen HK et al. (2022) Overestimation of COVID-19 vaccination coverage in population surveys due to social desirability bias: results of an experimental methods study in Germany. Socius 8:23780231221094749. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221094749

Wroblewski D, Brust-Sisti LA, Bridgeman M et al. (2024) Vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus prevention in older adults. Ann Pharmacother 0(0):10600280241241049. https://doi.org/10.1177/10600280241241049

Zhang S, Dieciuc M, Dilanchian A et al. (2024) Adherence promotion with tailored motivational messages: Proof of concept and message preferences in older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med 10:23337214231224571. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214231224571

Acknowledgements

We thank Kathy Benitez and Ashley West for their contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ESB conceptualised the project. ESB and SD hand-coded replies. ESB and AL conducted data analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript and interpreting results. Corresponding author: Amy Bucher. Correspondence to Amy Bucher, abucher@lirio.com.

Corresponding author